A master businessman, Walters was proactive about gaining the best exposure for his bands. In addition to performances in cabarets, at private parties and charity concerts, the Walters band regularly broadcast on radio. They also often performed in film shorts and newsreels, ideas taken from some of the big American bands. These films increased his band’s popularity, and set it up perfectly for an enthusiastic reception in New Zealand.

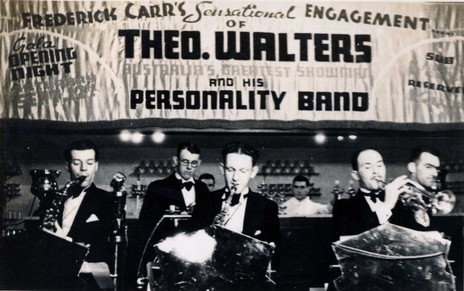

The Theo Walters Personality Band quickly became popular with local dancers and musicians.

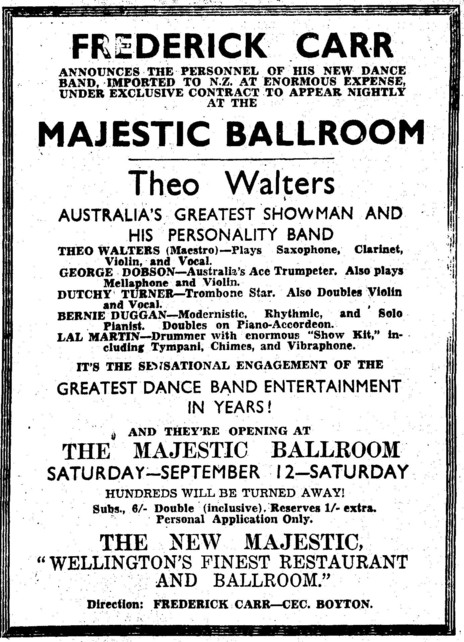

After its debut at the Majestic Cabaret, Wellington, in September 1936, the Theo Walters Personality Band quickly became popular with local dancers and musicians. The band consisted of Walters on saxophone, George Dobson on trumpet, Geoff “Dutchy” Turner on trombone, Bernie Duggan on piano and accordion, and Lal Martin on drums. The Majestic Cabaret appearances quickly proved that as well as looking the part of a first-class bandleader, Walters was a consummate showman.

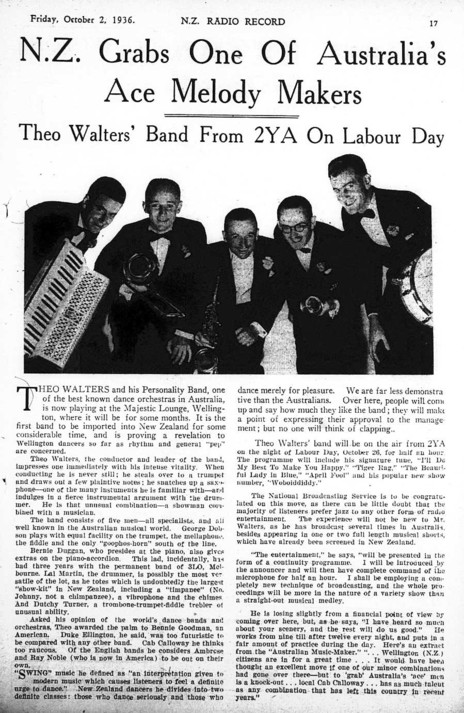

During its residence at the Majestic the quintet regularly broadcast on radio, usually via relay (ordinary phone line) to 2YA. The New Zealand Radio Record ecstatically previewed the band’s first broadcast in Wellington with a profile of Walters. The writer was impressed by Walters’s vitality: “When conducting he is never still; he steals over to a trumpet and draws out a few plaintive notes; he snatches up a saxophone – one of the many instruments he is familiar with – and indulges in a fierce instrumental argument with the drummer. He is that unusual combination: a showman combined with a musician.”

Then article enthusiastically described the band (they were “all specialists”) and quoted Walters’s opinions on the styles of swing bands around the world. Benny Goodman was his favoured style; Duke Ellington was too futuristic; Cab Calloway too raucous; English bandleaders Bert Ambrose and Ray Noble were “out on their own”. The article also listed a selection of the music to be broadcast, a mix of popular songs such as ‘A Beautiful Lady in Blue’, original compositions such as Walters’s novelty song ‘Woboididdy’ and jazz standards such as ‘Tiger Rag’. The article concluded by quoting the Australian Music Maker and Dance Band News saying it was quite a the coup for New Zealand to “grab Australia’s ace man.”

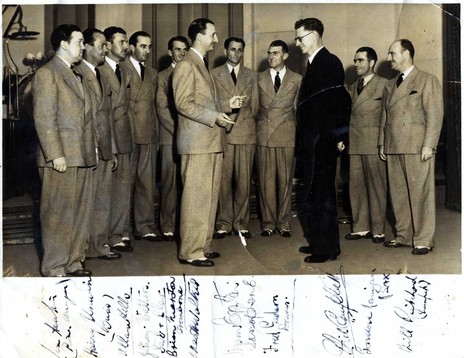

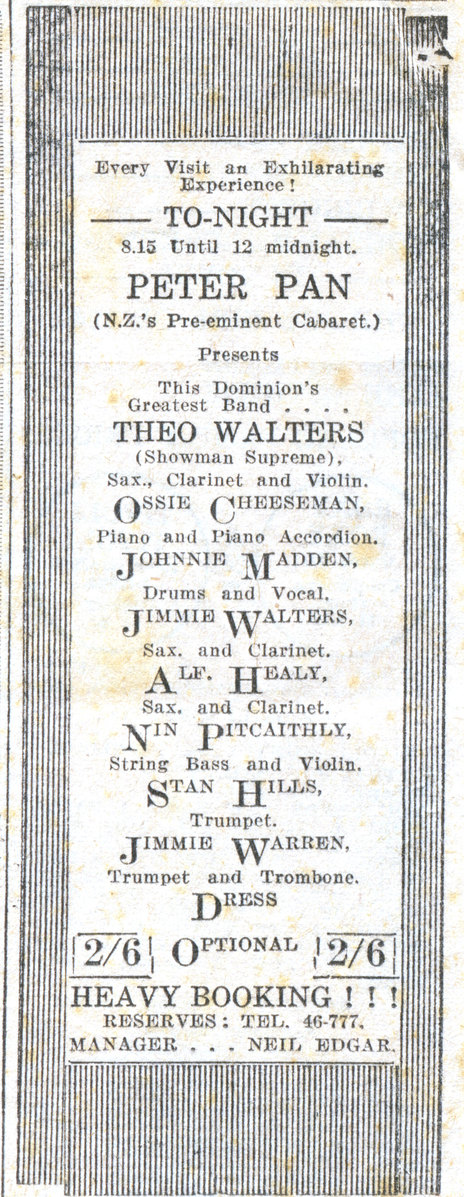

In early 1937 Theo Walters Famous Personality Band departed Wellington for a residency at the Peter Pan Cabaret on Auckland’s Lorne Street. Walters had expanded the Personality Band to feature – alongside his original Australian line-up – New Zealand musicians Baden Brown and Jim Watters on saxophones, Vern Wilson and Phil Campbell on trumpets, and George Campbell (brother to Phil) on bass.

The Auckland correspondent for Australian Music Maker and Dance Band News noted that the Walters band was of great “educational value” for the local jazz scene. The band was known for its instrumental versatility, its emulation of the Benny Goodman swing style and for the musicians’ showmanship. It was dramatically different from many New Zealand bands in this period. According to contemporary reports, New Zealand musicians’ concept of showmanship was virtually non-existent. In newspapers, women’s columnists were extremely impressed by the band, calling them “masters of syncopated rhythm” and praising their swing arrangements and musical versatility.

The Walters band also impressed Auckland musicians and audiences with their musical comedy skits between dance sets. Walters would dash around as a variety of characters, including a Cab Calloway type persona and the popular Olga the Beautiful Spy. The band played other characters or acted as “straight men” reacting to Walters’s escapades. The audience loved these items as much as the music and crowded around the bandstand in breaks to get in a good position to witness what the band would do next.

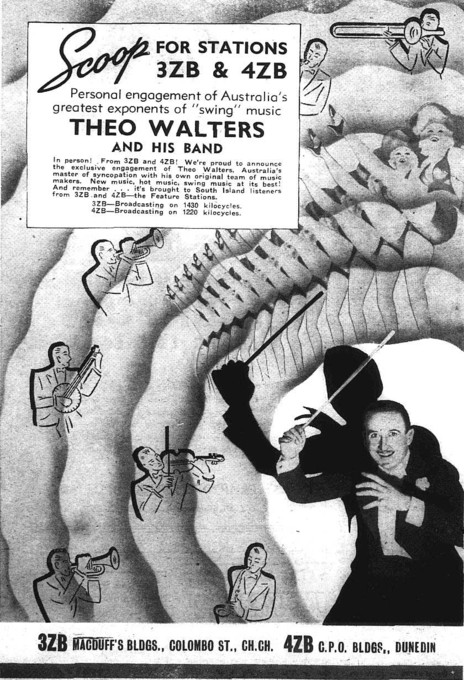

After their Peter Pan residency, in March 1937 Walters took the band on a short tour of North Island provincial towns. In April they returned to the Peter Pan for a second residency which lasted until September. Walters then took the band on a more extensive tour of New Zealand, which allowed its large number of fans outside of Auckland and Wellington to see them. Throughout its New Zealand tour the Walters band broadcast regularly on local radio, usually via relay from cabarets or theatres, but also from radio studios. In late 1937 they performed for the re-opening of 3ZB in Christchurch and 4ZB in Dunedin, as the National Commercial Broadcasting Service expanded its outlets. These two radio performances firmly established the Walters band on the South Island scene and the band remained there until Walters and the Australian contingent returned to Australia at the end of the year.

In late 1939 – after performing on the entertainment circuit in Melbourne and Sydney – Walters unexpectedly returned to New Zealand, without a band. This surprised musicians and audiences on both sides of the Tasman. He began his second New Zealand sojourn leading the house band at the Peter Pan Cabaret, and he was soon splitting this band’s time between the Peter Pan, theatre, and radio engagements.

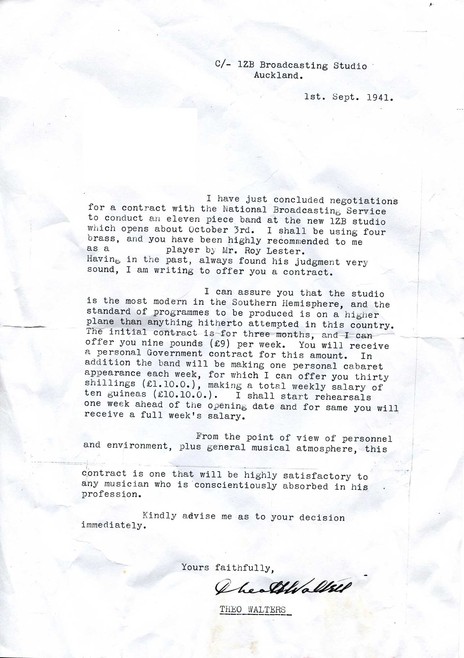

By the middle of 1941 Walters negotiated a contract with Auckland’s 1ZB for his band to be the station’s house band.

By the middle of 1941 Walters negotiated a contract with Auckland’s 1ZB for his band to be the station’s house band. This had the music industry buzzing: rumours suggested it was the highest-paid broadcasting contract in New Zealand. This was astounding because the New Zealand Commercial Broadcasting Service was notoriously parsimonious. The contract terms were very generous: for the initial three month contract the NZCBS would pay each musician £9 per week. Walters was also interested in having this band appear at “a cabaret” – likely the Peter Pan – for an additional 30 shillings per week, for a total of 10 guineas. To put this into perspective the average pay for a musician in 1941 was between £1 and £2 per gig.

The Theo Walters Personality Band became the house band for 1ZB – broadcasting from the new, art deco Radio Theatre on Durham Street – and the most prominent swing band in New Zealand. The band’s primary programme was Band Waggon on Friday evenings, a half hour showcase of its abilities, but the group also provided music for other programmes during the course of the week. Unfortunately, the war intruded and the band disbanded in late 1941 when Walters joined the Central Band of the Royal New Zealand Air Force.

Walters remained with the RNZAF throughout the war, eventually becoming the leader of its swing band, the Swing Wing, in 1944. Under Walters’s leadership the Swing Wing strongly resembled his civilian bands. A number of the personnel were taken from his pre-war bands and Walters utilised his showmanship skills just as much as he ever did in civilian life.

The RNZAF bands performed for both civilian and military audiences to raise war funds and to boost morale. Walters’s skills as a consummate showman were perfect for this situation. As well as straight concerts and playing for dances, Walters was also a driving force behind the Flying High Revue in mid-1944. The Flying High Revue was based on the variety format with band members taking part as characters in sketches as well as playing in a variety of combinations. This revue gave Walters full scope for his showmanship, and he created diverse characters and sketches for the amusement of the audience. According to a review in Wellington’s Evening Post the show “kept the audience … in a perpetual state of laughter”. It was a lavish show, and the highlights for the reviewer were the Symphonic Swing Orchestra (the Swing Wing with strings) and Walters’s creation the Hill Billy Hotshots. In this spoof country combo, members of the swing band sowed “instrumental corn” with swing arrangements of songs such as ‘Pistol Packin’ Mama’.

Near the end of Walters’s tenure as head of the Swing Wing the collective RNZAF bands embarked on a tour of the Pacific Islands. From June to September 1944 the bands (and the Flying High Revue) entertained Allied forces across the Pacific performing two or three concerts a day. The musicians were received with great enthusiasm, and American audiences particularly enjoyed the Swing Wing. Walters was praised as the master of ceremonies as well as for his leadership of the Swing Wing. One American serviceman wrote to the Evening Post to express his delight, saying that Walters’s “style of music and showmanship could be compared with any great named band in the States. The music, as we Americans say, was ‘solid’.” Other reports on the Swing Wing compared them favourably to the Artie Shaw Band which toured the Pacific encampments the previous year.

After Walters was released from military service in early 1945 he returned to Australia. Although he never came back to New Zealand, Walters left an indelible mark on the development of its jazz scene. His musicianship and showmanship strongly influenced the performances of local jazz/ dance musicians in the 1930s and 1940s, providing models that they could emulate in terms of sound, showmanship, stage behaviour, and improvisation.

Walters’s bands in New Zealand also became known as great venues of education, essentially the equivalent of doing a jazz degree, covering technique, performance practices, arranging and composition, and general musicianship.

He was especially noted for finding new talent, including trumpeter Jim Warren and singer Winsome Walsh. For both Warren and Walsh this was their first job with a swing band of this calibre and it taught them everything from sight-reading skills to improvisation and showmanship.

The New Zealand jazz scene is indebted to Walters as he influenced an entire generation of jazz musicians and helped create a localised swing scene.