“Woodstock Planned In Waikato” ran the headline in the New Zealand Herald. It had been a long time coming. Three years after the epochal Woodstock festival in upstate New York, New Zealand was still waiting for a Woodstock of its own.

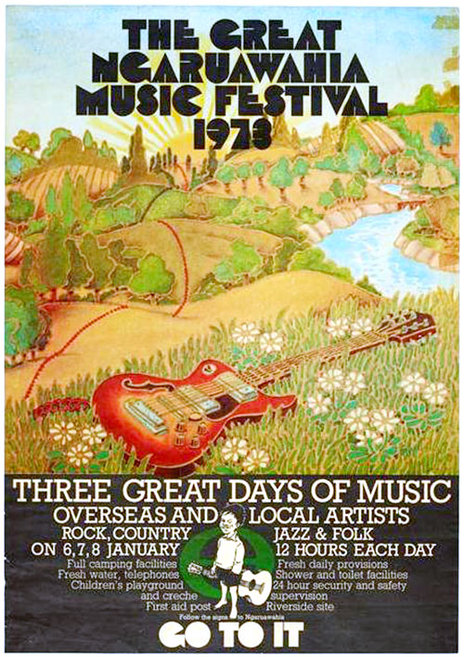

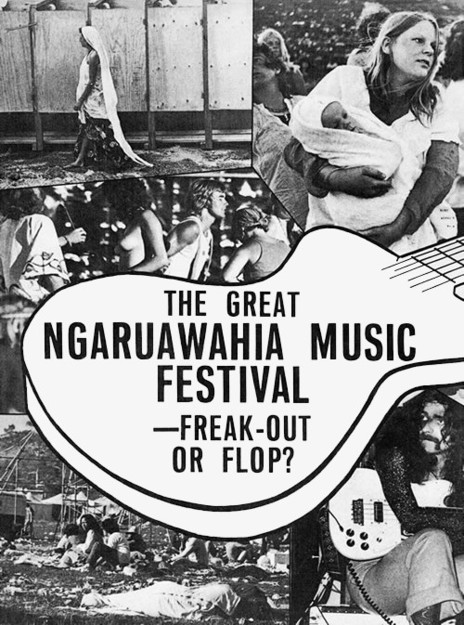

The Dick Frizzell designed Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival poster.

There had been festivals, but nothing like the three days of mud, music, good vibes and bad acid that had made Woodstock the crucible of the counterculture. The Moller’s Farm Blues Festivals had been running since 1968 but were more like a switched-on version of the folk and bluegrass conventions. Then there was Redwood 70, an all-weekend event in West Auckland promoted by veteran entrepreneur Phil Warren, but with a lineup dominated by mainstream television pop acts and headlined by a solo member of the Bee Gees, it was never going to have much countercultural cred. When mobs hurled fruit and rushed the stage during Robin Gibb’s solo set it began to look more like a westie version of Altamont. One-day festivals at Pekapeka and Englefield in Belfast, Christchurch, were also characterised by drunkenness and brawling.

Crowd shot, Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival. - David Stone

How would The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival differ? Held over three days, 6 to 8 January 1973, it was the brainchild of two bright young entrepreneurs with close enough connections to the counterculture to know they would need a more credible headliner than Robin Gibb. By the time he was 21, Dunedin-born promoter Barry Coburn and his Australian cohort Robert Raymond had already successfully held Elton John and Led Zeppelin concerts at Western Springs Stadium, the biggest rock shows the country had seen.

The stage awaits, Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival, 1973. - David Stone

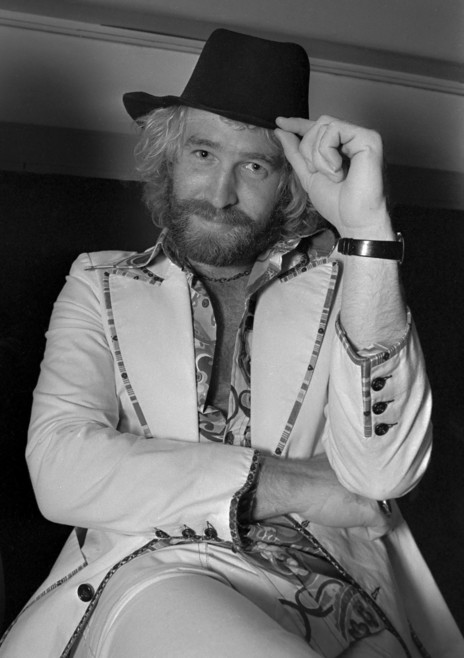

Raymond was a confessed pot-smoker and Values Party voter. He drove a Mercedes and had a posh Remuera house where he had entertained Led Zeppelin. Coburn, by contrast, was unassuming and, according to a 1973 profile in New Zealand Rolling Stone, “incredibly sincere”.

Robert Raymond, co-promoter of the Great Ngaruawahia Rock Festival and many other New Zealand music events in the early 1970s. - Bruce Jarvis

To headline their festival, Coburn and Raymond signed two international bands, Fairport Convention and Black Sabbath: a folk-rock and heavy metal pairing that represented the extreme poles of British rock at the time. The wide middle ground was left to be filled by local acts.

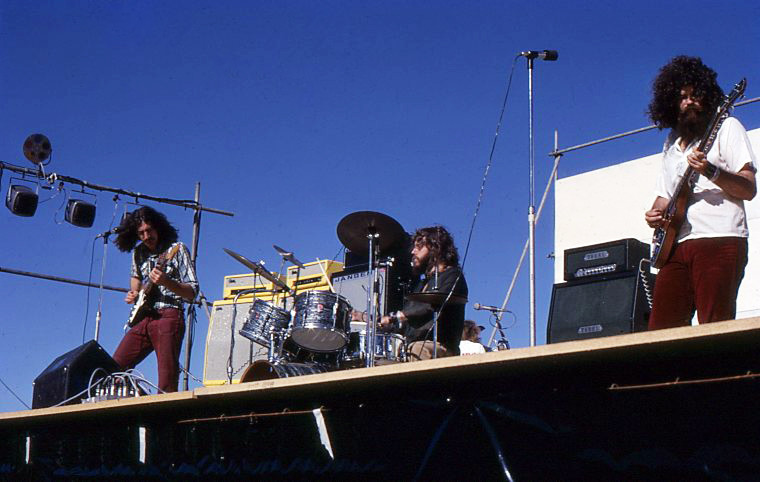

Fairport Convention performing at the Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival. - David Stone

There would be 40 food stalls, 50 showers, 100 toilets and a creche; a 40-strong medical team with hundreds of metres of bandages, gallons of sunburn cream and 500 tetanus shots. In anticipation, the two nearest hotels stocked up with almost a quarter of a million beer cans.

The Earwig Collective was commissioned to produce the Ngāruawāhia Chronicle, a four-page broadsheet containing the festival programme, profiles of a few of the acts and features on health food and ecology.

Hitching a ride to the Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival, 1973. - Dave Stone

The cover charge for the three-day event was $8. Among those who unpeeled $105 in 2020 dollars was David Stone, a music buff from the Waikato who would later work in the record industry. Stone took his Nikon camera with him and several rolls of colour slide film. Forty-seven years later these images are published for the first time on the AudioCulture page Ngāruawāhia: the David Stone album.

People began to arrive several days early. “A myriad of tents and coloured domes housing people, children, food, drink, medical supplies and musical equipment have transformed dairy-cow paddocks into a multi-coloured tent town,” the Dominion reported before the first notes had sounded.

Dusk at the Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival. - David Stone

The Merchant Adventurers of Narnia, Wellington retailers of hippie accoutrements, filled a bus with friends and merchandise – Indian clothes and fabrics, incense, roach clips and cigarette papers – and set up their on-site shop in a tent.

Unlike the uneasy mix of mainstream and underground performers at Redwood, the Ngāruawāhia bill favoured local acts with some countercultural caché. Though padded with a few pop voices (Shane, Shade Smith), most bands played original material of a kind seldom heard on New Zealand radio.

Shade Smith (ex-The Rumour) and Prism. - David Stone

The La De Da’s, based in Australia since the late 60s, returned as a stripped-down power trio. Another expat, Reggie Ruka, fronted Australian band Itambu and made a strong impression with his cartwheels and what Thursday magazine called his ‘erotic spider walk’. Tamburlaine and Tole Puddle provided a more pastoral flavour.

Split Ends, yet to become Enz, gave their first performance outside Auckland. But the mixed response to their semi-acoustic art songs suggested crowds weren’t quite ready for them, and they were perhaps not quite ready for the crowds – despite being under the management of the festival’s co-promoter, Barry Coburn. The newly formed Dragon, still several years away from stardom, also gave their first major performance that weekend, to a less than rapturous reception.

Ray Goodwin, Neil Reynolds, Todd Hunter – Dragon at the Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival. - David Stone

Fairport Convention came on just before sunset on the Sunday night, bringing crowds to their feet with their electrified jigs and reels. Sandy Denny, who had performed solo the previous afternoon, delivered a rousing climax with Buddy Holly’s ‘That’ll Be The Day’.

Waikato band Mandrake, fronted by future Manfred Mann frontman Chris Thompson, played one of their last sets before Thompson’s departure for England and, before long, international fame.

Arkastra, about to play the South Sound 72 festival in Gore, December 1972, then head north to Ngāruawāhia. Note the posters for the Great Ngāruawāhia Festival in the van's windows. From left: Harry Leki, Andy Anderson, Paul Reid, Peter Blake, Tom Swainson, Denys Mason.

After the sun went down, local campus favourites Mammal and Billy TK and Powerhouse played loud electric sets. Black Sabbath were scheduled for later that night. As part of the performance rider, they had ordered the construction of a giant wooden cross, to be set alight at midnight on the hill overlooking the amphitheatre, adding drama to the band’s entrance. In time-honoured Kiwi DIY fashion, Coburn instructed a few members of the local stage crew to knock together a cross out of a few pieces of four by two, but come showtime they had difficulty getting the wood to ignite. Eventually this was achieved with the help of various flammable liquids, releasing a plume of toxins into the evening air.

Black Sabbath's Tony Iommi and Ozzy Osbourne, Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival, 1973. - David Stone

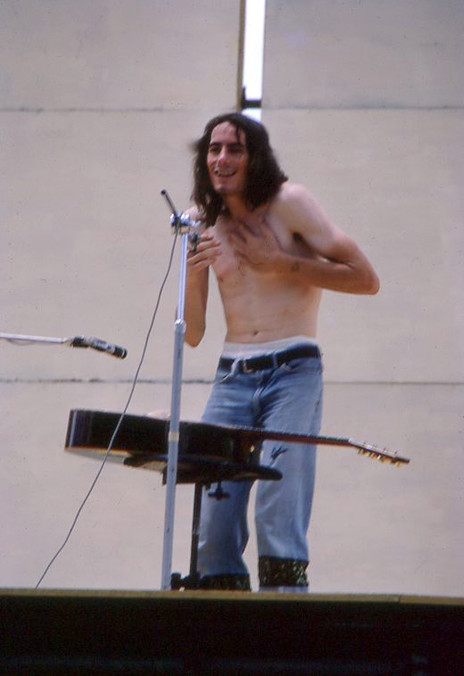

BLERTA was there, with both a children’s show and a typically anarchic jazz-rock set. It was their singer Corben Simpson who provided perhaps the festival’s determining moment, during a solo performance on the first day. After a few songs he declared he was hot, stripped off his clothes and played the rest of his set in the nude. Simpson’s gesture drew a line in the sand: society’s conventions did not apply here.

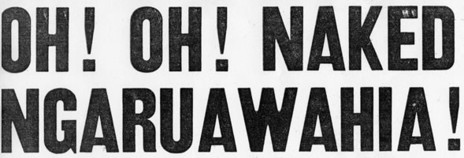

Nudity, onstage and off, provided salacious fodder for the mainstream media. It was the primary focus of a feature in the Sunday Times. “Oh! Oh! Naked Ngaruawahia!” gasped the headline as photos depicted unclothed women unselfconsciously drinking beer, flashing peace signs enjoying the festival.

Corben Simpson feeling the heat at the Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival, 1973. - David Stone

The overall tranquility of the festival may have had something to do with the light-handed way in which security was handled. Much of this task fell to Eden Security, a predominantly Māori firm run by Hugh Lynn, a former child tap-dancing champion and go-go dance instructor turned entrepreneur, whose first venture into security provision had been during the Pretty Things’ visit in 1965. As he told Cushla Donaldson in her impressionistic 2017 documentary Ngāruawāhia Sabbath, “Māori were very comfortable with large numbers of people – tangi, marae, that sort of thing – and there was an ease in communicating with people. We’re not going to arrest you for smoking dope or having sex. Taking your clothes off isn’t hurting anybody and we didn’t worry.”

Dancers at the Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival. - David Stone

Though attendance figures never reached the 25,000 Raymond and Coburn had hoped for, the 18,000 who came represented the greatest concentration of countercultural youth the country had seen. Despite some early alarms (“Drug scare sweeps festival” read one headline), drugs ultimately featured little in the reporting, and while LSD and marijuana were certainly present only two arrests for drug offences were reported. Neither was alcohol reported as being a particular problem, in spite of the quarter of a million beer cans.

The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival, 1973 – the aftermath. - David Stone

The Great Ngāruawāhia Festival – freak-out or flop? Thursday, February 1973

Although even the conservative press generally conceded that the long weekend had been something close to Arcadian, the festival’s aftermath played out in the courts. In June, Corben Simpson was convicted and fined for “wilfully and obscenely exposing his person” during his performance, while in 1975 a court hearing was told that the organisers of the festival had incurred a $50,000 loss. Robert Raymond recalled in 2020 that it took two years to pay the creditors, but he looks back on the event with fond memories. “We still celebrate occasionally, along with many folks who devotedly were an enormous part of the successful organisation. We were all pioneers really.”

--

Read more: Ngāruawāhia: the David Stone album

Trailer for Ngāruawāhia Sabbath, Cushla Donaldson’s 2017 documentary

NZ History: Reporting the Ngāruawāhia Festival

Split Ends recall their Ngāruawāhia performance (from Jeremy Ansell’s Enzology series, RNZ)

Black Sabbath's recorded set at Ngāruawāhia

--

Other early festival stories on AudioCulture

The National Banjo Pickers' Conventions

Sweetwaters on the rise - 1980 to 1982