The first thing you need to know about the popular Nambassa festivals of the late 1970s and early 1980s is that they weren’t Woodstock or Sunbury in Australia, or whatever convenient, but ultimately clumsy, cultural equivalent the media and authorities came up with.

Nambassa was a broader, more distinctly New Zealand event, out of time with those lauded late 1960s and early 1970s mega-events. The counterculture gatherings, centred in the Karangahake Gorge between Paeroa and Waihi in New Zealand’s North Island, celebrated what had already happened or was happening here, not what was still to go down.

The Nambassa experience was more akin to a multi-day A&P (agricultural and pastoral) show. A community and family event highlighting art and craft, music, new ideas, local produce, and the social, political, religious and cultural organisations that gave those communities energy and focus.

Festival organisers noted market days as another cultural parallel in Nambassa: A New Direction, the official account up to and including the 1979 festival, edited by Colin Broadley and Judith Jones and published by the respected firm A H & A W Reed Ltd.

“Market Days have quite a history in NZ. Most small towns still value their annual market days and usually the whole town turns out to take part. The demand for this type of business has been shown many times in New Zealand, hence the introduction of weekly markets like Cook Street, which has proved very successful over recent years. Every major city in NZ has at least one weekly craft market now, but only a few short years ago markets like these were unheard of in this country.”

The Nambassa experience resembled the contemporary Australian ConFests, established in 1976 by former Australian Deputy Prime Minister, Anti-Vietnam war protester and Marxist Jim Cairns, who would speak at the 1981 festival. However, key organiser Peter Terry didn’t hear about those events until Cairns contacted him in mid-1979.

“If there was an influence [it came] after the Waikino festival [when] I was handed a newsletter from the early British hippie 1970 and 1972 Glastonbury Fayre events, before their commercialisation,” Terry remembered in March 2014. “And walking around the Hamilton agricultural field days at Mystery Creek and being annoyed at the commercial marketing of chemicals in agriculture in part gave me the idea of showcasing the counterculture and alternative agriculture techniques, hence the workshops and social conscience groups. I'd had some involvement in early 1970s anti-Vietnam War and anti-nuclear campaigns.”

That aside, prime mover Terry and his organising committee knew music was a powerful part of the new equation and they’d use it extensively.

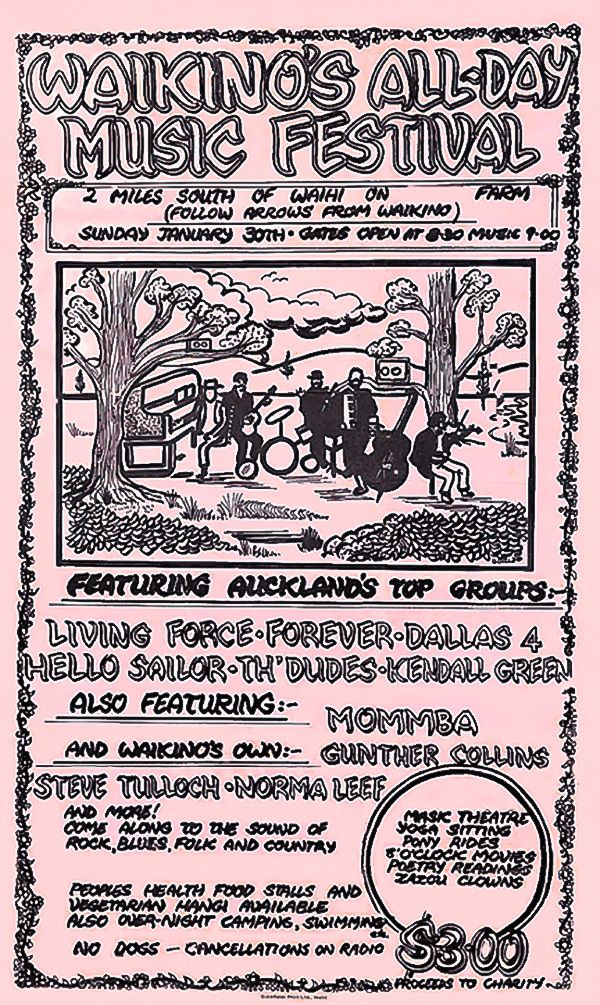

The Waikino All Day Music Festival on January 30, 1977, was the first notable gathering in the Nambassa experience. It was a music-centred event organised in support of the crafts village that had been established by alternative life-stylers in Waikino, an old mining and farming town above the Ohinemuri River at the southern end of the Karangahake Gorge.

Five and a half thousand fans turned up for the musical celebration, held at Bicknell's farm on Franklin Road in the Waitawheta Valley, to hear Living Force, Hello Sailor, Th’ Dudes and the long-lived Dallas Four, among others. All for the entrance price of $3. Unbilled appearances from Midge Marsden and The Country Flyers, Rockinghorse and Ragnarok supplemented the occasion and helped spark a spontaneous expansion from eight hours to a 24-hour event. Which must have got the long hairs excited, as they set about broadening the scope of the concert to a full-blown gathering of the countercultural tribes for the following year.

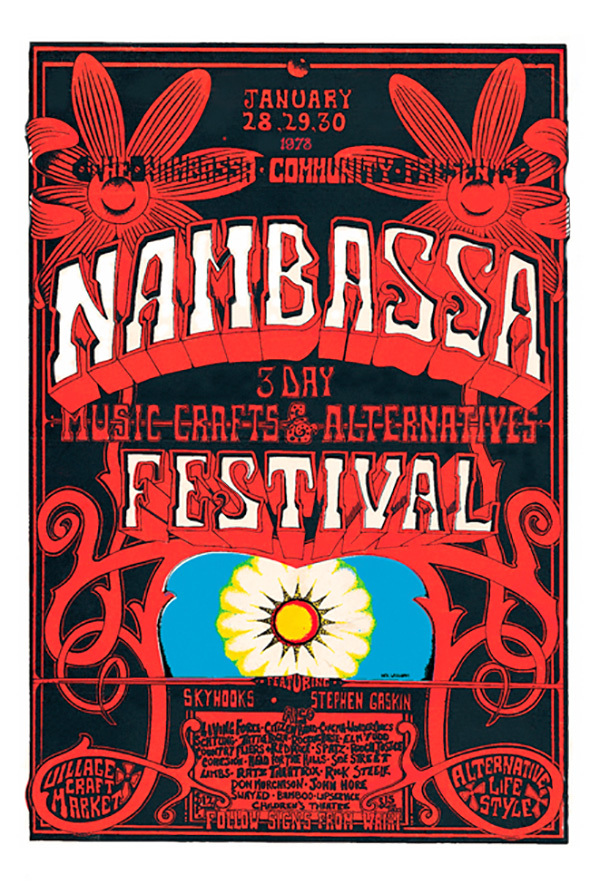

The 1978 poster

Nambassa 78

A new site was located at Phil and Pat Hulse’s 200-acre farm on Landlyst Rd in Golden Valley, south of Waihi, for what was now called the Nambassa Music, Crafts and Alternatives Festival. It was held on a grassed plateau above a white sand east coast beach over Auckland Anniversary Weekend on January 28, 29 and 30, 1978. For every visitor through the gate, the Hulse’s would receive 20 cents.

Nambassa founder Peter Terry in Melbourne in 1978, negotiating the Split Enz appearance at the festival

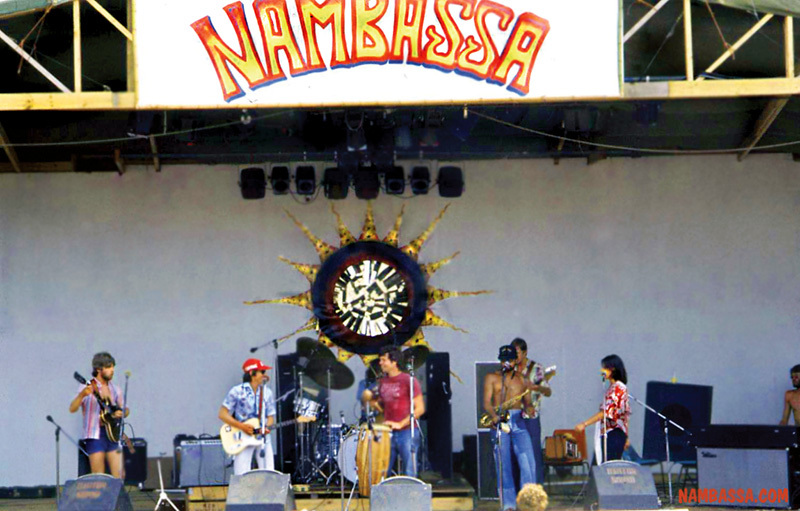

Swayed from Auckland on the main stage in 1978.

Skyhooks, the glam-ish Melbourne act who’d had great success in 1976 with the hit single ‘Blue Jeans’ and album Straight In A Gay Gay World, were lined up as the main musical attraction with a supporting bill of New Zealand performers. They were heard through an improved 5,000 watt PA managed by Auckland’s Harlequin studios, using staging that allowed the music to flow freely.

Living Force on the 1978 main stage

Ticket outlets throughout the North Island evidenced the broader alternative economy that the 1960s generation had established in the early to mid-1970s. In Auckland, tickets were available at Cook Street Market, Sunshine Books and Crazy Shirts (next to the Auckland Town Hall). In Hamilton, it was Heart n Soul Handcrafts in Ward Street. Tauranga’s Khala Sutra Craft Market at 12 Wharf Street had tickets, while Chelsea Records in Wellington serviced that countercultural centre.

Midge Marsden with Beaver and Andy Anderson on the main stage, 1978

On the Coromandel Peninsula where there were multiple communes, a visit to the Whole Earth Health Food Shop in Coroglen was in order. Closer to the epicentre in the Waikino Craft Village, you could pop into Bakers Dozen, School of Mines Museum and Bit O Sole Handcrafts. At successive festivals, tickets were made available in health food restaurants, head shops, surf shops, the Narnia markets in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch, and the raft of small city and town record shops which proliferated in the early 1980s.

Living Force in 1978

Just in case those in Auckland still hadn’t got the message, there was a parade down Queen Street in December 1977 that mooted the upcoming festival.

In total, there’d be over 150 covered stalls onsite representing “crafts, foods, amusements and action groups alongside alternative lifestyles and self-subsistence workshops.”

The good vibes matched the sunny weather, attracting between 15,000 and 25,000 people, almost twice as many than had been planned for. On the back of the undeniable success, another three-day event was planned for the following January on the same site.

Nambassa 79

If the numbers attending in 1978 were, at the very least, surprising, Nambassa 79’s estimate of 45,000 to 65,000 attendees was simply astounding. No one had predicted the three day festival of music, crafts and alternatives would be that popular. Not the organisers, who estimated 25,000 people might arrive, or the authorities. There hadn’t been a youth orientated gathering of that size in recent memory and definitely not one conceived and run by the counterculture.

Schtüng on the main stage in 1979.

Golden Harvest's Kevin Kaukau in 1979.

Returning to the Hulse’s Golden Valley farm for a second time in late January gave the festival a sense of continuity. It also meant traffic was snarled up to Paeroa in the north and Waihi in the south and site facilities were overtaxed. When the masses got to the idyllic spot, their tickets were checked by the Values Party, a new and sympathetic national political force that had snared five percent of the popular vote in the 1975 general election. Presales cost $13 for adults and $6 for nine to 13 year-olds. Ten thousand advance tickets were sold this way. If you rolled up on the day, the entrance price increased to $16 for the whole event with a graduating scale downwards for the following two days.

Little River Band at the 1979 festival.

Looking out from the main stage, 1979

It wasn’t just the crowds that were bigger. There was now a 7,000-watt PA system in place. The music bill was longer as well, although the music mix was similar to the previous year. Little River Band, an Australian group at the height of their popularity, headlined. Golden Harvest, an NZ contemporary hit band, were also there, and Split Enz, who were rebuilding their fan base after their early art rock and British OE years.

Split Enz on the main stage, 1979 - Photo by Susanna Burton

Eddie Rayner, 1979

Caught just short of their most popular phase, Split Enz’s manic ‘I See Red’ barely made the pop charts in June. Their next album, Frenzy, would be a big seller and precursor to the knockout punch of ‘I Got You’ and True Colours. It helped that the group hadn’t toured New Zealand since September 1977 and had a strong university following.

Commenting on the ease and tolerance with which “60,000 people can live together in a tent city”, February’s Rip It Up reported the music “kicking off with Sheerlux — new wave covers and an over-mannered lead singer” before Schtung brought precision and polish and new drummer Brian Waddell to the stage. Split Enz arrived an hour and a half late in bitingly cold winds. “Not a good gig,” RIU concluded.

The Philip Howe-directed movie of the festival, Nambassa Festival (which can be streamed below), shows Split Enz kicking hard live, despite having lost much of their band equipment in a fire at a local hall, where they’d been rehearsing.

New Zealand’s most important group of the 1970s were featured on the Festival Music double album when it was released in December 1979. The rest of the sounds came from local groups, including Living Force, Flight 77 and The Plague or soloists with established NZ fan bases like Chris Thompson and John Hore. Chapman and White, one of the duos on the double album, had already released a single called ‘Nambassa Song’ celebrating the event. The show’s MC was Andy Anderson, replacing Grant Bridger, who’d been the compere at previous festivals.

The Sam Ford Verandah Band, 1979.

A more intimate musical experience could be found at the Aerial Railway stage, which featured at all the Nambassa festivals and the new Sweetwaters festival. Another product of Coromandel Peninsula communes, the Aerial Railway studio found much favour in the 1980s.

The broader Nambassa gathering was largely peaceful and positive as the Nambassa Festival film’s interviewer found when recording vox pops from the laid-back crowd. When controversy flared it was over policing of drug laws onsite and the pay levels of New Zealand performers. Ever-present NZ protester Tim Shadbolt had little success in organising around the latter issue. But heavy-handed policing of drugs laws proved a much bigger concern after 58 arrests. Spurred on by conservative grumblings after the Marijuana Party’s 500 person smoke-in at the 1978 festival went unmolested, local police were under pressure from Wellington to take a tougher line on drug use, which set off an extensive counter-reaction.

The Plague on the main stage, 1979 - Photo by Gerald Couper

Eight hundred people marched on the police caravan. There were no arrests, but some threats were made from the crowd, adding to 37 arrests before Sunday morning. Organiser Peter Terry intervened and the arrest count dropped to just three. But it wasn’t enough to stop up to 3000 festivalgoers marching on the police caravan at 7pm on Sunday evening.

All of which highlighted another societal change. As historian Redmer Yska points out in New Zealand Green, his 1990 history of marijuana’s presence and influence, by the late 1970s middle New Zealand was getting its freak on in a major way. Supplying cannabis had been made a minor offence in July 1975 with the Misuse of Drugs Act, and marijuana, homegrown and imported, was now widely available and used.

Responses to Nambassa’s permit applications to the Ohinemuri County Council revealed more specific local apprehensions and prejudices as well as practical concerns. “Inappropriate use of land” and “nudity, drugs and occult heathen religion” were cited in opposition. Some saw the festival as “detrimental to the community, especially young people” in promoting “a wrong attitude to work and dignity of labour and an encouragement to young people not to settle, but to drift, and evade public responsibilities.”

Worries were aired that Nambassa (a largely spiritual grouping itself) represented “a growing anti-Christ involvement,” while others perceived “a lack of morals causing embarrassment and upsets to the community as a whole.” Objections to “undesirable behaviour, open sex, drugs and advocating alien belief systems” were also raised.

These were very much prejudices of their time, and in some cases they were understandable, but they’d recede in the years to come. The counterculture would never fully leave the area and many confronting ideas worked their way into rural society and farming practices over time. The “disruption to farming” one objector pointed to would ultimately be more intellectual and practical as One Direction indicated in citing the case of John Blake, the County health inspector, who had an interest in alternative farming methods.

Local organisations were actively involved in the festivals. The Legion of Frontiersman helped with parking. Hauraki Māori culture groups performed. Money was donated to local groups and pensioners. Mayoral support was offered by Owen Morgan in Waihi, the area’s most liberal town, and Auckland’s Sir Dove-Myer Robinson. Only Paeroa’s conservative Christian Mayor (and soon to be MP) Graeme Lee opposed it.

Reaction on the national political level was varied. Youth Initiatives funding was secured from the QE 2 Arts Council as well as a grant from Department of Internal Affairs, which Minister Allan Highet said needn’t be repaid, which indicated some degree of government acceptance. The NZ Literary Fund and QE 2 Arts Council had stalls on site.

Okay, the stage was set. Now, where did all those tens of thousands come from? New Direction catalogued the various subgroups present as “The people who didn’t think wearing clothes was necessary, and the spiritual people, the earthy types, those in costume with exotic hairdos, people with umbrellas (for shade), walking sticks or wheelchairs, the “head buzz” freaks, the ponderous types, the ravers, the sporty outdoor camping types, the bikie boys, the bored ones looking for a new buzz, it was a visual circus enriched with a multitude of expressions, voices and laughter.”

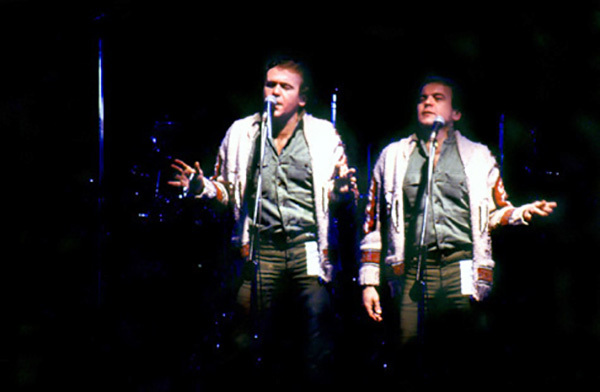

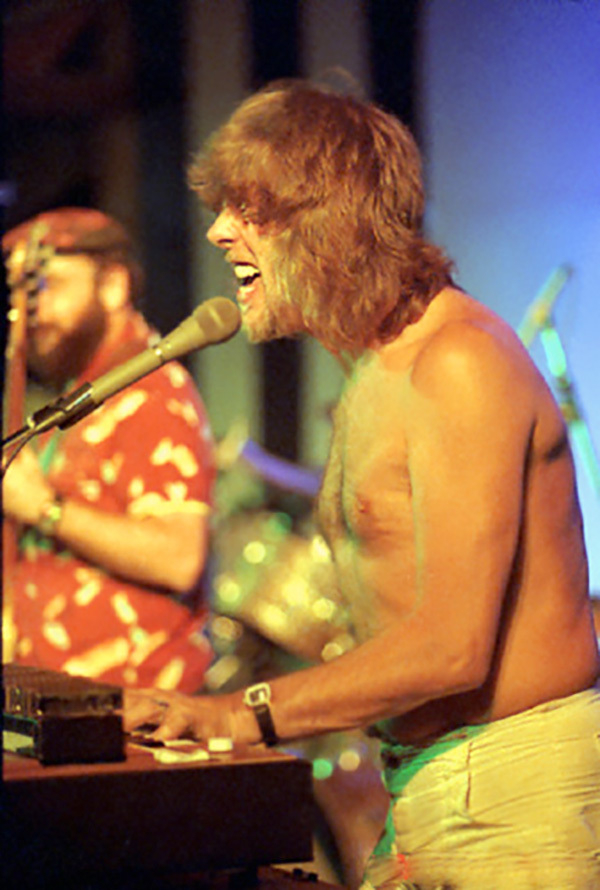

Glenn Shorrock of Little River Band on the main stage at Nambassa 1979

The net for potential attendees had been cast wide. The Nambassa organisation produced its own media. The Nambassa Sun newsletter began publication in early 1978 and ran through into 1979. Five thousand newsletters were made available in New Zealand, and 2,000 in Australia, where the festival event was also marketed. There are some anecdotal accounts of a trans-Tasman hippie trail in the 1970s. Tim Shadbolt, in his second autobiography, A Mayor of Two Cities, pointed to a high degree of interaction and information sharing amongst the new generations.

“We (the Huia commune) had always been a highly mobile commune; we travelled all over the country, visiting other communes. The hippie grapevine was brilliant, so we could follow the progress of BLERTA or the Ohu scheme because of the hundreds of visitors who stayed with us for a few days, weeks or months before moving on.”

Other media outlets available to the organisers, included the then five-year-old alternative lifestyle magazine, Mushroom, published out of Waitati in Otago, and the Whole Earth Catalogue, as well as campus newspapers. Mainstream media covered the festival as well.

It’s likely the large-scale single headline band events at Western Springs in Auckland and multi-centre Town Hall shows had whetted the appetite for mass communal gatherings around contemporary music. The 1970s in New Zealand saw the arrival of many of the greats of the 1960s music explosion as well as some of their influential forebears. The Rolling Stones were here in 1973 as was Leon Russell, Yes, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Slade, Caravan, Lindisfarne and Status Quo. Rod Stewart and The Faces, Jethro Tull, B.B King, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and Rick Wakeman arrived in 1974. Joe Cocker, Eric Clapton, Wishbone Ash, Lou Reed and Roxy Music came in 1975. Santana, Frank Zappa and Fairport Convention were visitors in 1976. Jeff Beck and Fleetwood Mac had big shows in 1977. David Bowie’s outdoor concerts in 1978 were massive affairs.

The Negative Theatre on the main stage, 1979

The New Zealand universities circuit, marshalled by the Student Arts Council, was active throughout the 1970s, sponsoring BLERTA campus tours in April and May 1975, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee, Flo & Eddie and Canned Heat in 1976. Country Joe McDonald and Kevin Coyne came in March 1977, locals Schtung in April 1977 and Leo Kottke in March 1978. Annual Student Arts Festivals rotated around the nation’s campuses throughout the 1970s, giving many countercultural organisers experience in event organising.

Another big part of the festival’s appeal was its display of alternative lifestyles and ideas by spiritual, lifestyle and political groups. The counterculture had manifested itself in New Zealand in many ways by the late 1970s and had in some cases connected up with older dissident groups. The wide-ranging collection of organisations and activities on interactive display at Nambassa represented a broad infusion of mostly new (to New Zealand) ideas and perspectives. Sometimes they were ideas from different cultures, at others, older ideas and methods from our past, both Pākehā and Māori.

Although by 1979, only three of the rural communes (known as the Ohu scheme) mandated by the Labour Government of the early 1970s were still functioning, the rural exodus of middle class young from the cities was still in evidence.

Tim Jones and Ian Baker’s A Hard Won Freedom: Alternative Communities in New Zealand from 1975 outlined a number of existing communal groups throughout the country. They found new communes in and around Christchurch and Auckland and existing communes at Beeville in the Waikato, and the breakaway Wilderland, who’d provide food for the 1979 event and 309 near Whitianga on the Coromandel Peninsula. There was the Reef Point commune near Ahipara and later in Taranaki, the long-lived Rainbow Valley commune and Moonsilver Forest at Takaka and Golden Bay.

While many were short-lived and friction existed with conservative locals, there was an upside for everyone. The newcomers brought new ideas as well as their labour and families and helped spark a subtle broadening of the rural economy.

One Direction indicates that a very real appetite for pre-industrial country life existed in the late 1970s. It was anti-urban, with a preference for co-operative activity against competitive endeavour and a bias to the communal as opposed to the individual. Ecological concerns were strongly voiced and actioned.

The community organisations present in large numbers at Nambassa allow yet another view of the diversity within countercultural New Zealand in the second half of the 1970s. Groups including the Tarot Workshop, Ananda Marga, Laughing Man Institute, Friends of The Western Buddhist Order, the Agape community, Self Realisation Fellowship, Spiritual Women’s tent, Bible Society, Buddhadharma, Yoga Pyramid Healing centre and Open Air Campaigners all had stalls on site.

Which didn’t stop the tabloid press via old reliable Sunday News simplistically summing up the event as “Nudity, drugs and loud music.”

Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee look out from the Redhat stage, 1981

Nambassa in recess

Where to go from there? The 1979 festival returned a profit of $200,000 to the Nambassa Trust, which announced plans for a grouping of cooperative communities in the Waitekauri Valley with a school and businesses for up to 50 families. There wouldn’t be another festival until 1981, the organisers announced.

Spying a gap in the market, Nambassa functionaries, including Daniel Keighley and Paul McLuckie, began to organise Sweetwaters, a new music and cultural festival to be held near Ngāruawāhia in late January 1980. Finessing the Nambassa experience, the organisers found a site more readily accessible by road and rail and other improvements were made in site egress, stage sound, water and toilets. The music bill was also more contemporary, reflecting a recent resurgence in live music in New Zealand. Those factors combined for another successful and well-attended festival, the first of four Sweetwaters.

Peter Terry: “The untold story here is Sweetwaters 80 was run with my blessing. I had other interests and didn’t intend to run festivals for the rest of my life. After Nambassa 79, I furnished Daniel and Paul with all my contacts and even walked their Ngāruawāhia site, advising them how to best place their facilities. We had a gentleman's agreement that I would run a final Nambassa in 1981 and Sweetwaters would have a bye. They broke the agreement, the rest is history, that’s life.

“Daniel fronted at the Mother Centre in late 1977, looking for a job. He had no background in entertainment or marketing. He said that he wanted to organise a concert in Auckland with the proceeds going to Amnesty [International]. At Nambassa 78 and 79, he worked for me as a volunteer with our on-site construction crews. He even toured the Nambassa winter show late 1978, acting in a rock opera I had written. Contrary to what I’ve read, Daniel had nothing to do with any of the organisational aspects of Nambassa.”

In the short term, Namabassa fans had to content themselves with a touring North Island beach festival in early January 1980, featuring Hamilton folkie Chris Thompson, fire eating and a talent contest. The film of the 1979 event was previewed on the tour. Filmed from the air and on the ground at the site, it’s a relaxed and revealing snapshot. But the success of Sweetwaters had told and the organising collective announced an extended five-day festival for the same weekend as their new rival in late January 1981.

A hui the Original Travelling Roadshow and their band Mahana held at their housetruck circle at Nambassa 81.

Nambassa 81

The final Nambassa festival wasn’t without controversy. Planned originally for a more accessible site at Onetai near Hikutaia, north of Paeroa, Ohinemuri County Council baulked and the prospective location was shifted to Franklin Road in the countryside around Waitawheta. It was a “clean comfortable environment” with a mountain river running through it.

Returning to the area around the Karangahake Gorge wasn’t without challenges of its own. One month out from the festival, Ohinemuri County Council slapped an injunction on the event as farmer and area concerns were dealt with. The five day festival rolled on. The array of groups and organisations in 1981 would be even larger than in 1979.

The Topp Twins on the Redhat stage at Nambassa, 1981 - a festival of "peace, love and barfi".

The music this time had a rootsier, more international feel, with heritage greats John Mayall, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Daniels Band and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee supplementing the equally varied local contribution. The music on the day would be heard through The Musical Pyramid – the largest ever sound system in NZ provided by Cerwin Vega with “115,000 watts of dynamic and clear sound, ¼ million watts light on a 70-foot high pyramid with laser beams.” Bet that looked good on acid.

Onsite-media would include the Nambassa Waves newspaper, which was published early each day and had been available at the two previous festivals, and Radio Nambassa Land, which could be heard in Paeroa and Waihi.

John Mayall on the Redhat stage, 1981

Nambassa 81 was announced to the wider music-going public with a full-page ad in Rip It Up in November 1980. Tickets were $27 or $22 if you paid by Christmas. There’d be plenty of onsite activities to keep visitors of all ages busy. The Red Hat Theatre showcased politics and performance with the open air theatre hosting over 60 groups. 120 workshops were planned. Outdoor movies, an on-site bakery, hot air balloons, talks on the Coromandel’s mining controversy and Arts in NZ, displays by painter Michael Illingworth and talks by hippie thinkers and doers, including Stephen and Ina May Gaskin and Baba Ram Dass (Dr Richard Alpert) sprinkled the programme.

Representatives from American Indian and Aboriginal populations were present. The Craft Market – “Handmade crafts – No Factory Processed Junk” – had over 50 stalls that highlighted wood-adzing, the art of airbrushing, Raku pottery firing, leather goods, weaving, woodcarving, glass blowing and tie-dying.

This was clearly a diverse community with a lot energy left in it, but with Sweetwaters stripping away many prospective attendees the last Nambassa had to settle for cultural rather than popular success. Which probably pleased folks like Tim Shadbolt, who derided the 1979 event as “overcrowded (and) over commercialised” with too much government input.

Dizzy Gillespie on the Redhat stage in 1981

Nambassa 81 attracted fewer than 10,000 visitors and lost $40,000 to $50,000. It would be the last large-scale festival. If a final act was needed, it came in May 1981 when the Ohinemuri River rose to unprecedented heights, flooding the Karangahake Gorge and Paeroa and wiping out the roadside businesses in Waikino that had sparked the first event in 1977. But ideas don’t die and neither did the memory of the Nambassa festivals. It’s a legacy that Peter Terry curates to this day.

Watch the complete Nambassa Festival documentary from 1979 at NZ On Screen:

–

Close Encounters of the Weird Kind: the Topp Twins at Nambassa

All images courtesy of, and © Peter Terry & Nambassa Trust.