The foreword to Peter McLennan’s book Deepgrooves: a record label deep in the Pacific of bass, and the people who gave it a voice (Auckland: Dunbar Noon, 2024).

--

Where to start with Deepgrooves Entertainment? A record label that was both of its time and place and one that in large part, more than any other, defined that place and time. Deepgrooves had an almost perfect catalogue, but one that never realised its vast potential because it was surrounded by almost perfect chaos in its conception, its creation, its oversight and, sadly, its legacy. That is, until Peter McLennan’s book arrived to give the label created by Kane Massey, Mark Tierney, and Bill Lattimer – but overseen for most of its almost-decade by Kane – its rightful due.

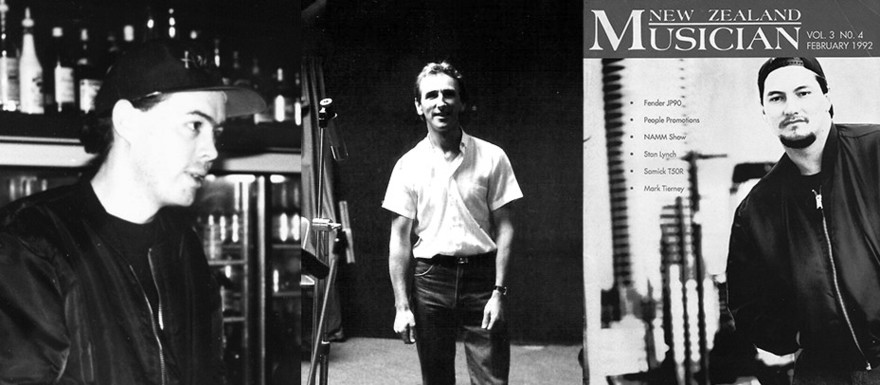

Left to right: Kane Massey, Bill Lattimer, Mark Tierney.

Deepgrooves, too, aside from that mighty catalogue, also left us with as many stories, urban legends – as Kane, from time to time insists they are – and unanswered questions. Questions that this book hopefully addresses, although it opens another nest of questions in doing.

Deepgrooves arrived as Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland underwent an almost seismic cultural shift at the tail end of the 1980s and early 1990s, when a nearly moribund ghostly inner-city was kicked back to life by the arrival of Pasifika and – specifically – by an invasion of young Polynesian people from both South and West Auckland. With them, they brought fresh style, captivating, unique music, and radical rhythms. It was an invasion that was also embraced by a new generation of usually Pākehā kids arriving from the inner-west, the east and the North Shore.

Various Artists - Deepgrooves (compilation, 1992)

In retrospect, somebody was always going to create Deepgrooves. Every generation (arguably skipping the early 1970s) in New Zealand has had its key indie labels capturing the essence and sound of the streets and there’s a good argument to be made that Deepgrooves was the spiritual successor to the very first locally-owned record label, Tanza; a label that, more than any during its lifespan, documented the sound of the clubs, dancehalls and airwaves of 1950s Auckland.

I’ve forever kicked myself that I didn’t do something like Deepgrooves. I was in the perfect place as an inner-city club owner amid the city’s musical revolution and I did jump in a year or two later with Nathan Haines and OMC.

However, to create something like Deepgrooves took an almost irrational and enthused passion (as do most indie labels) and both Kane and Mark had just that.

To create something like Deepgrooves took an almost irrational and enthused passion.

More, in a pre-internet country with (then) around four million people, a very niche label documenting minority music in one city of a very regionalised country was always financial madness. With Deepgrooves the madness seemed to match the passion and this book grapples with that, especially via Chris Sinclair’s fascinating memories. Everyone has a Kane story (I do) but Chris was in the eye of the storm and it’s clear his massive technical talent (and patient sanity) was a huge part of why Deepgrooves was able to create such an extraordinary catalogue. Anthony Ioasa was another monster talent, without whom ...

However, central to all of this was Kane Massey’s probably irrational devil-be-damned drive and relentless boundary-testing, possibly backed by a belief that one day that hit record, one that will make it work, will arrive. The opportunity for such a hit – a worldwide success – was gifted to him by his Sony deal but, for whatever reason, be it disorganisation or disenchanted artists, there was no follow-through, and the opportunity was lost.

Almost nobody in this book has universally good things to say about Kane but there is a much-deserved aura of respect too. He frustrated just about everyone he worked with and habitually overpromised.

However, the reality is that without Kane Massey very little, if any, of the music written about in this book would ever have been made, let alone released. He delivered musically and culturally, over and over, which – it could and probably should be argued – satisfied the intent and broad vision of the grants system he played so. He created an often sublime and groundbreaking body of work that Aotearoa is so much richer for.

And – yet – it’s so Kane that here we are in 2024, frustrated (yet again) by the lack of Deepgrooves recordings available to us. It’s a legacy that exists more in writing and visually than in sound. What is available is largely so because the artists and enthusiastic third parties have made it so, and have found a way to extract it from Kane.

We’ve been teased over the years by promises of a vinyl box set which never arrived; the odd album has appeared on streaming services only to disappear; a website was live and threw up incredible images with enticing stories of a deep unheard archive before it too disappeared. Kane posts on social media now and then, giving his contradictory version of events – followed by more silence. The Grace album, Sulata, the Deepgrooves double 10” EP and much more are all unforgivably missing in action.

For all the traumas, the dramas and the stories, the reality is Deepgrooves remains one of the most important catalogues of music from Aotearoa – ever – and yet it doesn’t exist in any tangible, coherent form. Until it does, this long overdue and fascinating history, addictively compulsive and comprehensive in its detail, will have to suffice and tease.

Kane, where are you?

--

Deepgrooves: A record label deep in the Pacific of bass, and the people who gave it a voice by Peter McLennan, 2024

Peter’s links to Deepgrooves articles

--