Since the 2000s began, the worldwide music industry has undergone a seismic shift, moving from a CD-dominated business model to one that relies primarily on digital distribution. This change has had a profound effect in Aotearoa, with musicians having greater access to international listeners than ever before, though this requires standing out from an extremely crowded marketplace. For the majority of artists the financial return is low.

The arrival of the MP3

In the 1990s, CD sales were booming, though the cost of releasing an album was comparatively high. Musicians with commercial aspirations usually had to record in expensive studios, then their work had to be pressed onto compact disc (at a few dollars per unit), and distributed to stores. Artists often relied on gaining advances from record labels to be able to afford to put an album out.

Major record labels were in a particularly dominant position and sometimes manipulated consumers to gain the greatest profit. For example, some labels largely stopped releasing CD singles so that customers were forced to buy a whole album even if they only wanted it for the hit song it contained. The OMC hit ‘How Bizarre’ wasn’t released as a single in the US and therefore was ineligible for the Hot 100 singles chart, with consumers having to buy the entire album instead (the album reached No.39 on the Billboard 200 album chart).

The 1990s saw the creation of the MP3 file format, small enough to be sent over the internet

The 1990s also saw the creation of the MP3 file format. CDs held music as digital files, but the format they used meant the files were too large to send over the internet, especially with the slow data speeds of the time. However, researchers in Germany found that the human auditory system can only process certain elements of an audio signal at one moment, so they created a much smaller file size by weeding out elements that weren’t perceived (or difficult to perceive), such as frequencies that cancelled each other out.

The result was the MP3, which held music as a small digital file, though with some loss in quality. It was named after a global working group, the Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG), who were attempting to create a set of audio/visual standard formats. The official name they assigned – “MPEG-1 Audio Layer III” – was shortened to “MP3”.

Savvy internet users began sharing music as MP3s, and websites such as MP3.com began illegally hosting songs for free download. A watershed moment came when canny programmers realised that if users were willing to open up their computers to one another, then files could go back-and-forth without restriction (known as “peer-to-peer” file sharing). The most notorious peer-to-peer service was Napster, which started in 1999. Rather than hosting MP3 files, the site effectively provided a connection point for files to be shared among users. The music industry realised Napster was an existential threat, so they sued it into non-existence (with one prong of the attack being a separate lawsuit fronted by Dr Dre and Lars Ulrich from Metallica).

It wasn’t long before new file-sharing sites emerged, such as Limewire and Pirate Bay. The music industry responded by suing individual users who had downloaded illegal files. Some record labels also introduced “copy controlled” CDs that couldn’t be easily turned into MP3s, or creating “digital rights management” software that meant files could only be listened to on a certain music player.

A CD by The Brunettes, released through EMI with a sticker showing that it has copy controlled software on it

New Zealand innovators

In the late 90s, Auckland entertainment lawyer Chris Hocquard read an article in Wired magazine about MP3.com and decided he needed to engage with this new technology. Hocquard was on the board of bFM at the time and worked with a couple of friends from the station, Jubt Avery and Johne Leach, to create a website where users could legally purchase MP3s by local bands.

The business first launched in 2000 as MP3.net.nz, and was soon renamed Amplifier. However, the majority of its income still came from selling physical products – mainly CDs. What’s more, only independent bands and labels could sell digital music through them, since major labels were still in a pitched battle against the rise of the MP3.

The landscape then changed with the arrival of two large international players into the digital music market. The one that many people associate with the period was Apple, which launched its iTunes software as a music player in 2001, then began turning it into a music store from 2003 onwards. Music purchased as digital files could then be transferred to portable music players, primarily Apple’s own iPod players. The store launched with only 200,000 songs, which sold for US99c each (though using the AAC file format, which was higher fidelity than MP3s).

The power of iTunes globally was shown when Brooke Fraser achieved her first breakthrough in the US when her 2006 album Albertine (2006) was listed as an Editor’s Choice on the iTunes homepage. It sold 16,000 copies in two months, half of which were digital copies, enough to push the album to No.90 on the US album charts.

Apple had a strong competitor in the early years, with Vodafone launching its own music service, Vodafone Music. Its head of music in New Zealand was Morgan Donoghue, who already had over a decade of experience in the music industry with EMI/Virgin and Big Day Out. He hurriedly sought deals with the major music labels, so that Vodafone Music could launch before iTunes in New Zealand and, in 2006, managed to get ahead of them by a week. Users were able to purchase music which they could then download to play on their phone or on their computer.

Donoghue also wanted independent artists to be available on the platform, but he didn’t have the capacity to deal with hundreds of small artists/labels. He asked Hocquard to do him a favour by getting Amplifier to act as go-between. This made Amplifier into an “aggregator”: a company which acts on behalf of musicians to supply their work to digital outlets. When iTunes launched, Amplifier played a similar role.

“I wrote to Vodafone: ‘I don’t know what you guys are doing, but you’re really f****** up my shit in New Zealand’.”

Vodafone Music was incredibly successful and Donoghue found that week after week the company was selling over half of the singles bought in New Zealand. Yet the issue of digital rights management remained. Listeners were still accustomed to purchasing music and then owning it in perpetuity, but songs bought from Vodafone Music could only be played on its mobile player or desktop application. Donoghue believed that either rights management would have to be removed – so that users could play the music they bought on multiple players – or users would have to be given the option of a “subscription model” where they paid a monthly fee to listen to as much music as they wanted.

Donoghue soon found things moving in the opposite direction. “The global president of digital at Universal Music, Rob Wells, called me and said, ‘We’re pulling Universal’s catalogue from Vodafone globally. You can keep the catalogue for your service in New Zealand, but I can’t give you the subscription rights or remove the digital rights management software.’ So I wrote a note to the Global Head of Content at Vodafone and said, ‘I don’t know what you guys are doing, but you’re really fucking up my shit in New Zealand. Can you sort your stuff out?’ I turned on my BlackBerry in the morning, half expecting to have been fired, and found they’d sent me a plane ticket to fly to the UK that night.”

He flew to a meeting in the personal boardroom of Universal Music CEO Lucian Grainge, which included all the company’s MDs from across Europe and the top management from Vodafone. Deals worth tens of millions of Euros were discussed and then fell by the wayside, without the central issue being resolved. Donoghue left the meeting without much hope, but Rob Wells called him over as he was leaving.

“He said to me, ‘Morgan, let’s go wakeboarding.’ To be honest, I didn’t even know what wakeboarding was. So he explained how you’re towed behind a boat on a lake. I told him that I’d go and get my togs, but he already had a swimsuit for me to wear. It was obviously all planned ahead of time. So he and I left together and everyone from Vodafone looked totally confused. We arrived at this private members club near Terminal Four of Heathrow Airport.

“It turned out Rob was really good at wakeboarding – he was doing flips and everything. Then it was my turn. I couldn’t even stand up. Then he said, ‘If you get up this time, then you can have digital rights management free rights for New Zealand only.’ So I focused as hard as I could on what I was doing and managed to stand up, then I did three laps. I gave him the finger, just before I finally came a cropper. Afterwards I went back to my hotel where all the Vodafone guys were and they asked what happened. I said, ‘I got my deal for New Zealand.’ They said, ‘What about us?’ I told them, ‘Oh, that’s not my responsibility. You’re still fucked.’ That’s when they offered me the Global Head of Music job based in London.”

Ringtones were another source of revenue for musicians during this time, with mobile phone users paying to download short versions of songs to play when they received a call. The phone company Telecom (now Spark) even ran an award ceremony for the most popular ringtones. However, the launch of the iPhone in 2007 ushered in the smart phone era and ringtones died along with the flip phones that had held them.

However, as CD sales fell through the floor, iTunes and Vodafone Music weren’t able to stem the losses within the music industry. A new model was needed and it gradually became clear that the subscription model would win out.

New Possibilities and Pitfalls

Donoghue’s main aim as Global Head of Music at Vodafone was to launch a subscription service. Vodafone’s main competitor was a start-up called Spotify which first launched in 2009 in the UK, though it didn’t reach the US until 2011 and finally got to New Zealand the following year.

He befriended the team at Spotify and often found himself socialising with them at music industry events. By 2010, it seemed as if Vodafone Music might have the upper hand in Europe.

Donoghue describes one dinner he had with Spotify founder Daniel Ek and Fred Davis (son of CBS/Arista executive Clive Davis) an investment banker who has been behind some of the biggest deals within the global music industry. “Daniel said that they had 250,000 subs and were going to announce themselves as the biggest subscription service. I told him, ‘We’ve got a million subs, with half a million in Spain.’ Vodafone had created a bundle where people in Spain could get unlimited data and unlimited music for 12 Euros a month. It went gangbusters.

“After that we worked on a joint venture with Nokia called ‘Project Auckland’. Nokia jokingly named it after my hometown, but it stood for ‘All You Can Keep Land’. It was basically like Spotify, but with no DRM, so you could download unlimited music and it was yours to keep for free after you stopped paying the subscription. We drove that really hard, but it was just a bit early. We had a deal with three of the four biggest labels, but Sony held out. We’d offered 350 million euros, but they wanted 420 million euros. I could see we were just too far apart, so I pulled the pin on it. After that, I felt like I just needed to do something else.”

Morgan Donoghue with Rhianna, backstage at the O2 Arena concert in 2010.

Donoghue moved back to New Zealand in 2011 and took up a role at Serato. Meanwhile the music industry still hadn’t agreed on a way forward. Vodafone Music was limited by its clunky digital rights management software. If you switched devices it was hard to use, and it didn’t work at all on Apple phones or computers. The iTunes platform became increasingly hard to use with each iteration, and was particularly annoying for users with music players other than iPods.

The atmosphere within the music industry became increasingly desperate. Revenues had halved, which led to layoffs at the major labels and a run of mergers. Record stores also seemed like they might be a dying breed.

At the same time, there were some signs that the new, interconnected world might have an upside for some local musicians. They could now put their music online and have it heard by a person on the other side of the planet. The main platform for doing this was Myspace. The site was originally intended to be a social media website where users could connect with one another. A user’s “top friends” was the key connection point and they could share their interests. In 2007, Myspace was launched in New Zealand with a secret show by Evermore; by the end of the year it already had 400,000 users here. More secret shows followed, including one by UK group The Cribs.

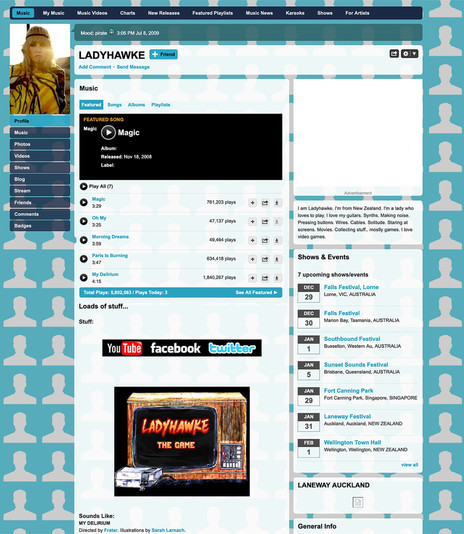

Musicians were able to post a handful of songs on their Myspace page and if they were well-connected with other bands then it provided a useful discovery tool. One local act who benefitted from Myspace was Ladyhawke, who’d already made a name for herself on the Australian music scene as part of Teenager (with Nick Littlemore from PNAU/Empire of the Sun). By early 2008 she began to get a buzz in the UK market.

Ladyhawke’s Myspace page allowed listeners in the UK to check out her music as soon as they heard her name. It also helped that she was listed as one of the top friends of PNAU, as their own star rose. She did her own bit to highlight musician friends from back home by having a friends list that included acts such as Julia Deans, Charlie Ash, and Holiday With Friends.

Ladyhawke's Myspace page in 2010

Ladyhawke hit No.16 in both the UK and Australia in October 2008, though her popularity could also be tracked online. In previous decades, when New Zealand musicians headed overseas it was hard to tell back home exactly how well they were doing. Now there were new metrics to consider. By 2011, Ladyhawke’s song ‘My Delirium’ had been listened to 1.8 million times on Myspace.

Myspace itself was in decline by this stage. Facebook had taken its place as the most popular social media platform, helped by the fact that users could constantly post new updates (Myspace pages were more static). Musicians soon followed the move across to the new platform.

YouTube was also on the rise. It eventually allowed fans to access music by relatively unknown acts

YouTube was also on the rise. It launched in 2005 and was bought by Google the following year. However it lagged in popularity until the price of internet data made it affordable for people to view videos without worrying about using up their monthly data allowance. YouTube also provided Ladyhawke fans with a way to access her music and, by the end of 2011, the video for ‘My Delirium’ neared five million views across two different versions.

YouTube also allowed relatively unknown musicians to break through. In 2011, Mt Eden Dubstep reached 24 million views with their track ‘Still Alive’, giving them an international fanbase even before most listeners at home had even heard of them. Naked and Famous took advantage of the possibilities of YouTube by filming part of their video for ‘Young Blood’ in the US, so that its visuals would have a sense of familiarity to audiences there. It gained ground organically until it had tens of millions of views, without ever touching the US charts (though their debut album reached No.91 in the US).

The most striking digital breakthrough of this era was Lorde. She put out her Love Club EP as a free download and it blew up. Once the interest had reached fever pitch, the free version was removed and her song ‘Royals’ became a US No.1.

These were exceptional cases and for most acts it was still an open question as to how musicians could turn online interest into a sustainable career. It would be a while until streaming took over and, in the meantime, it was clear that the internet held the key to the future of music listening.

--

Read more – From MP3s to Streaming, part 2: harnessing the internet as a music discovery tool