Read From MP3s to Streaming, part 1, here

--

In 2011 Brendan Smyth, the Head of Music at NZ On Air, wanted to harness the internet’s potential as a music discovery tool. He approached Chris Hocquard’s team at Amplifier to help.

Hocquard explains: “He had a strategy for New Zealand music, which was what he called a ‘Bedroom to Boardroom’ approach. He was trying to find a way to get a bedroom artist up to a level where they could successfully apply for funding and then NZ On Air could help them along. There had been an explosion in the number of indie labels in the first decade of the 2000s and they helped many bedroom artists develop in that way. However when NZ On Air removed their album funding, a lot of those labels disappeared. So Brendan wanted a way to fill that gap and The Audience was an attempt to do that. It tried to help musicians at a grassroots level and give them the opportunity to develop to the point where they started to slot into the system. That’s all it was ever meant to be and it worked well, to a point.”

‘The Audience’ platform allowed local bands to upload and promote their songs, which were then ranked by users

The Audience allowed local bands to upload and promote their songs, which were then ranked by users. Each month the highest rated artist was given $10,000 in funding from NZ On Air. Acts would compete to gain attention and highlight their work. While The Audience initially showed an ability to gain listeners for new artists, Hocquard had his reservations.

“Over the years, I’ve often seen these indie musicians who aren’t willing to say, ‘I don’t really know what I’m doing, I need some help.’ Those types of people were too cool to be seen being involved with The Audience. We could have got them there in the end, but that attitude did lead to scepticism from some quarters. Then we had a couple of acts who managed to game the system. There was one group in particular who were a Kiwi hip hop act based in Australia. When they won funding through The Audience, there was an outcry. We quickly found a way to fix that problem, but the long-term plan was to remove that whole side of it all together. The funding was only intended to attract people in order to launch the site.”

Hocquard’s team adjusted the system so any “gaming” by acts not genuinely popular couldn’t occur; they also brought in more editorial content to ensure worthwhile acts were front and centre.

Meanwhile, Smyth was in the process of leaving NZ On Air. A new consultant was brought in to create a digital strategy for the organisation, and she criticised The Audience as not generating enough streams, despite being a music discovery tool rather than a streamer. The Audience had its funding discontinued and was eventually mothballed. It has since re-emerged as a YouTube MCN (multi-channel network) focusing on New Zealand entertainment content.

The Mixtape: a website where users could create their own online compilations

Some of the other projects funded by NZ On Air over this period now seem anachronistic, but were attempts to find a positive way for the internet to work for musicians. In 2012, James Coleman, an ex-TV host from channel C4, used NZ On Air backing to create The Mixtape: a website where users could combine the available tracks into their own “mixtapes”. It was promoted by the inclusion of mixtapes created by celebrities, including Jacquie Brown and Bret McKenzie. It is remarkable to reflect how it correctly foreshadowed the power that playlists would soon have, though the arrival of Spotify to New Zealand that same year made The Mixtape redundant.

Street Chant as portrayed in the Indie Music Manager game

An equally short-lived product that came out of this period was the 2013 iOS/Flash game Indie Music Manager, in which players guided the careers of rising musical acts. It was promoted as a way to “gamify” music discovery. It launched with 28 tracks by local artists (such as Princess Chelsea and Tiki Taane) and these played a key role in the gameplay. Unfortunately it is extremely expensive to create a video game and even the generous backing of NZ On Air wasn’t enough to avoid the game having endless bugs. A reviewer for The Corner, Michael McClelland, claimed it was “technically unusable after only four short levels”.

The Streaming Era

It took a while for Spotify to take its central place within the music industry. The clearest sign that streaming had taken over was in 2015 when Apple switched its focus from the iTunes store to starting its own streaming service, Apple Music. Despite consumers initially being wary about digital rights management software, it turned out that the solution was to make the experience seamless between devices. The user wouldn’t own any of the songs accessed via their subscription, but they would be able to use it on any mobile device, tablet, or computer which they owned. This made the issue of ownership less of a barrier.

Hocquard’s favour to Donoghue that led to him setting up Amplifier as an aggregator turned out to be a very lucrative business decision. His company eventually created a standalone company to provide this service under the name Digital Rights Management. The role of aggregators became even more important in the streaming era, since musicians weren’t able to supply their music directly to Spotify, Apple Music, Tidal, etc. Instead they had to sign up with an aggregator, who ensured their music files and images were in the right format before delivering them to the streaming providers, usually for a one-off upfront fee and a yearly management fee.

The role of aggregators became even more important in the streaming era

Hocquard credits DRM’s success to the other partners he brought on board to join him.

“There were at least 20 companies that set themselves up as aggregators at first, but the advantage we had is that we already had relationships with most of the independent artists. I also went to Peter Baker and Roger Marbeck, who were running the distributor Rhythmethod, and asked to do a deal with them because they had Fat Freddy’s Drop and a lot of other big local artists. The last thing I wanted was for them to turn around and become an aggregator as well. At that time, physical was still outselling digital around seven-to-one and so they weren’t really interested in digital, because they were selling shitloads of CDs. So I gave them some shares in DRM. Then a bit later, we went to Stebbings and asked if they wanted to become involved, because they were sitting on this goldmine of content from years past. So that’s how we pulled together a huge amount of New Zealand music onto the one aggregator.”

DRM as aggregator: from the NZ music industry publication MayBook (Stellar Night Productions, 2010)

DRM became a major player in the local music industry, with Chris Hocquard and his partners selling the company to US aggregator/distributor The Orchard in June 2024.

Spotify and Apple Music weren’t the only streaming services to have an impact in New Zealand. Soundcloud launched in 2007 and gradually developed a more open model, where musicians could upload songs with less chance of being sued for uncleared samples, which made it a home for DJs doing remixes and rising hip hop producers. A strong community gradually developed, though the downside was that the income from plays on Soundcloud is extremely low, even compared to the other streamers. One local rap artist who found early fame through the community on Soundcloud was lilbubblegum, who uploaded his track ‘af1’ in 2019; it gained five million streams. He then developed the interest into a more lucrative career via other services such as Spotify (where, by March 2025, ‘af1’ had reached 125 million streams).

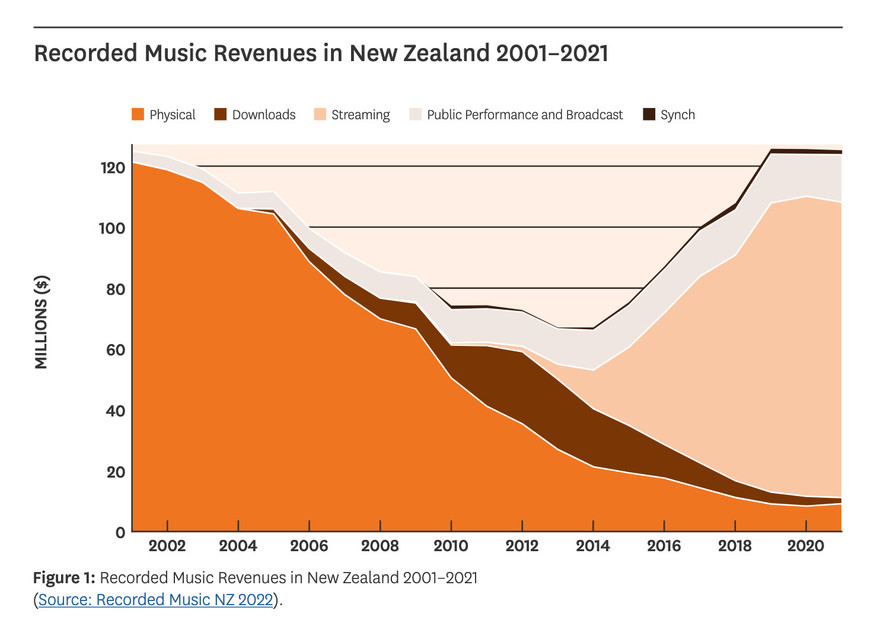

The rise of Spotify and the other streamers was a boon for established record labels with a large back catalogue. In the CD era, it required serious investment to reissue an old album and distribute it to stores, so the majority of their past releases were only available secondhand. In contrast, the streaming era meant they could make their whole catalogue available at a tiny cost and were able to negotiate a higher income rate than independent artists. The turnaround for the New Zealand music industry was startling.

NZ Music Industry Revenues 2002-2020

The situation was less rosy for artists, particularly those at the lower-to-middle range of success. In the CD era, a rising act could press a run of 100 CDs and expect to gain a return of at least NZ$1000 (even more, if they sold them directly to fans). To achieve a similar level of income via streaming, they would need upwards of 500,000 streams. However, the numbers given in this comparison are necessarily approximate since calculating an artist’s expected streaming revenue is very difficult.

Streaming revenue is calculated in a rather convoluted manner

Streaming revenue is calculated in a rather convoluted manner. Take Spotify for example. The income for a particular track is derived from its percentage of the overall streams on Spotify: the available income is then divided between all the eligible tracks (those with over 1000 streams within a year).

One potentially unfair element of this system is shown by the following example: if a person pays the full premium subscription cost of $18.99 per month and only streams Fat Freddy’s Drop, it doesn’t mean the band will receive the majority of this income. This led Mikee Tucker (Loop) to work on Baboom, an alternative streaming service which would proportionally assign the money from a customer directly to the acts they streamed (minus the company’s cut). Baboom was funded by Kim Dotcom, but failed to get off the ground. Tucker instead adjusted to the prevailing system, setting up Loop as its own aggregator, as the major labels did.

On Spotify, streams that come from premium/paid accounts generate a higher rate, as do streams for artists on major labels – as Spotify shareholders the majors negotiated a better rate for themselves. In New Zealand, there are a higher number of users with premium accounts since Spark provides its customers a cheap bundle deal. This means that an act such Six60 which gets most of its streams within New Zealand is able to gain a higher rate per stream than acts who rely more on streams from overseas, where free accounts are more common.

However, in most cases an act requires a huge number of streams to be able to make a living with their music. To paraphrase the character of Sean Parker (Napster) as portrayed in David Fincher’s 2010 movie The Social Network: “A million streams isn’t cool, you know what’s cool? A billion streams …”

Viral Superstars

The upside of streaming for musicians in Aotearoa is that their music is now instantly available to a worldwide audience. They no longer have to face the near-impossible task of getting their CDs into overseas stores and convincing radio stations in those countries to air their music. However, the mammoth amount of music being uploaded means that it is increasingly hard to gain attention. Nonetheless, a small number of local artists have managed to find a sustainable career via this route.

The most obvious success stories are the dozen or so local songwriters who have written (or co-written) songs with a billion streams. AudioCulture has an article on this topic, The Billion Streamers. Suffice to say, once a song reaches this level of streams then not only is the direct revenue a decent amount, there are also other sources of income: royalties for having it synched on a movie or series; ad revenue generated by the music video on YouTube; songwriting royalties when it is broadcast on radio or other formats.

The world of music discovery has also changed. In some cases, it might go viral within Spotify itself. For example, if the algorithm presents a track to new listeners and they don’t skip past it, then the algorithm will continue to present the track to increasing numbers of people and it could be added to official Spotify playlists. This was the path taken by the Shouse track ‘Love Tonight’ co-written by New Zealand producer Ed Service (that is, until David Guetta got involved and did a remix).

newer apps have also created viral hits – TikTok is the most obvious example

Other newer apps have also created viral hits. TikTok is the most obvious example. On TikTok songs are often used as the backing for dance routines, which can be widely watched. Benee’s track ‘Glitter’ blew up in this manner. TikTok gave an even greater boost to her track ‘Supalonely’.

Songs are also used on TikTok as a way to metaphorically represent the sentiment of a clip. That is how the Princess Chelsea songs ‘Cigarette Duet’ and ‘I Love My Boyfriend’ gained views. Chelsea already had tens of millions of YouTube views from an early burst of online interest in ‘Cigarette Duet’ and a decade later she found herself with hundreds of millions of new views/streams.

Songs don’t need to be current releases in order to find success via this route. The 90s hit ‘How Bizarre’ by OMC was the perfect backing music for videos of “bizarre” happenings on TikTok. It has purportedly gained over a billion streams on TikTok, but unfortunately the royalties paid by TikTok are calculated in a unique manner, with a payment made per video in which a song appears (rather than the amount of times the song plays in the app). Nonetheless, the interest saw streams of ‘How Bizarre’ double within a couple of years, from 100 million to over 200 million.

The success of an act like Princess Chelsea might put her at a lower level than a billion streamer like Benee, but there are a number of local musicians finding a sustainable career with a similar level of success: hip hop acts including SXMPRA, 9lives, and lilbubblegum; indie acts such as Lontalius, and pop acts Drax Project and Robinson. There are also beatmakers/producers whose work has appeared on gold and platinum certified albums in the US, but who are not well known at home, prime examples being SickDrumz and LMC.

The importance of YouTube has grown over the years and become an important source of revenue to the music industry. YouTube accounts can now gain revenue from the advertisements that accompany their videos. It is predominantly relevant for labels rather than individual artists, as the barrier to receiving ad revenue requires at least 1000 subscribers and 4000 hours of view time over 12 months. For the most part this has only been accessible by major labels, though some indies such as Flying Nun and Lil Chief Records are also at this level.

The outlets where listeners find music are continually evolving. One of the biggest streaming success stories to come out of New Zealand is indie act Salvia Palth, who first found fans through Pinterest before becoming a streaming juggernaut on Spotify. Occasionally his monthly listener numbers have surpassed nearly all other New Zealand acts, the exception being Lorde. At the same time, there are other acts who solely upload their music to Bandcamp, as users of this service are more likely to pay for the music they listen to (many listeners use both Bandcamp and streaming services in tandem).

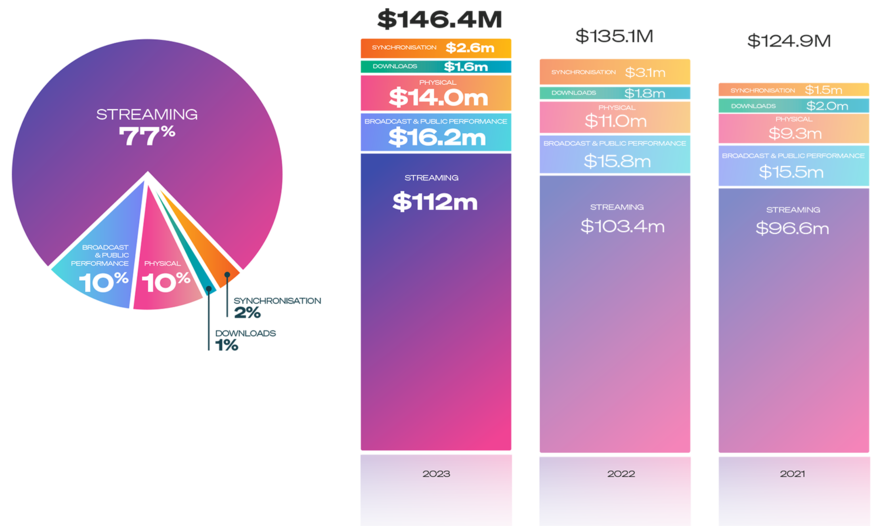

New Zealand Music Industry Revenues in 2023

The success stories above make it hard to simply say that the streaming era has made all musicians worse off, certainly when compared to the illegal downloading era. Though Wired magazine recently claimed that the business model of streaming has been “good for listeners and labels but bad for both streamers and artists.”

There are also new hurdles on the horizon with AI music beginning to challenge concepts of authorship, and Spotify creating its own music to fill certain categories – for example, employing their own ambient composers to fill out those playlists. While Spotify retained an editorial team in Australia, artists from both sides of the Tasman found it harder to get noticed by the team among the onslaught of music being added daily. There were also suggestions that bots were being used to give some songs an artificial boost to get them started.

The first 25 years of the 21st century has seen a tremendous amount of change take place in the music industry, and looking forward, there are few signs that things will settle down any time soon.