Chris Hocquard first entered the music industry as a lawyer but has taken a surprising number of roles alongside his legal work. He founded the country’s first independent MP3 store, created the streaming aggregator DRM, and co-owns a record label and management company that has launched a run of internationally successful acts. His varied work has given him a unique insight into the local industry and he has sometimes been the one to speak out when he has seen it moving in the wrong direction.

Chris Hocquard in 2008

Chris Hocquard’s interest in working in the music field came to him gradually. While studying at Victoria University of Wellington, he organised the Orientation/Capping events, which included helping to book the bands that performed.

When he was admitted to the bar in 1987, he was interested in working in the entertainment field and took a job at the firm Macalister Mazengarb specifically because he knew one of the owners was chair of the Broadcasting Committee, so he hoped entertainment-related jobs might come through this connection. Instead he largely did conveyancing, which he enjoyed since the task of hammering out deals between two parties usually left them both feeling happy at the end of the process (in comparison to more combative court work).

After a few years, Hocquard headed overseas on an OE, taking up legal work in the UK to pay his bills. His flatmate managed the band Magic Roundabout, which included Peter van Fluit (Screaming Mee Mees). They had a minor hit and began recording with well-known producer Youth, but the album was never released. Hocquard was fascinated and even met the band’s lawyers, but never really progressed things, though it did encourage him to eventually return home and build a business from the ground up.

Dominion Law

Back in New Zealand, Hocquard met with entertainment lawyer and former Netherworld Dancing Toys singer/ guitarist Malcom Black. “He was working for a practice called Sinclair Black. His partner Mick [Sinclair] did work for the film industry. Malcolm basically told me, ‘don’t bother, there’s no money in it, I’m struggling myself.’ There wasn’t enough work to even sustain one specialist music lawyer. I got a job at the Grey Lynn neighbourhood law office. I wanted to change the world, but eventually realised the world wasn’t going to change. So I set up on my own. I think I was largely unemployable – I didn’t fit the mould of a lawyer and didn’t want to fit the mould. I knew criminal law and was qualified for legal aid work so I began doing that.”

Hocquard decided that his best hope of getting into entertainment law was to work with the people in the industry that Black didn’t represent. Rather than approaching the artists, he connected with promoters, production companies, lighting specialists, and others who created the infrastructure that the scene relied upon. This led to the creation of his practice Dominion Law, which was named after Dominion Day, the one holiday a year that only lawyers took. Postioning the practice halfway down Dominion Road also appealed to his sense of humour. His first big job was working for Doug Hood and Bridgit Darby who ran the New Zealand leg of Big Day Out.

His options suddenly opened up when Malcolm Black got in touch to say that he was taking a job at Sony. Hocquard arranged to purchase his company, but unfortunately he already had a holiday booked to Thailand, so there was little in the way of handover and he had to find his feet by himself. He bought a textbook about music law and set off for a holiday.

The first music deal he worked on was helping arrange a deal with Polydor for dance/pop group, NV (singer Liz Fa’alogo, guitarist Neil Becker, and beatmaker/producer Andre Upston). He entered further into the music industry via the other well-known music lawyer active at that time, Campbell Smith.

“Campbell had started doing a bit of entertainment law and management. He was acting for Bic Runga, Garageland, and the Shortland Street cast. He decided to be a full-time manager and moved to the UK with Garageland to try to make that work. He was the chair of bFM at the time, and he asked me if I would take over [Hocquard stayed in the role from 1997-2014]. Campbell also did the law-line slot on breakfast as Roy the Lawyer, so I replaced him. Though I kept things more straightforward and just called myself Chris the Lawyer.”

Music industry legal deals were “a huge wild west” in the 80s; by the late 90s there was still a lot to straighten out.

Hocquard found that some of the legal deals that were taking place around in the late 90s still left a lot to be desired.

“It was a huge wild west right then. It wasn’t as bad as it had been in the 80s and early 90s. I think Campbell and Malcolm had done a reasonable job of straightening it out, but there were a lot of small labels run by entrepreneurs that signed bands up to recording and publishing deals while promising the earth. The good thing about that time is the majors were particularly active. EMI had a strategy of dominating New Zealand music, then there was growth of FMR that combined the reach of Mushroom and Festival Records. There were also a few artists starting to make money, whether it was The Feelers and Fur Patrol on Warner or Bic Runga and Stellar* on Sony. The whole move to digital was just starting and that’s what kept me interested.”

Upheavals

When Hocquard left for his Thailand holiday after acquiring Malcolm Black’s practice, he not only took his new textbook but a copy of Wired magazine that he bought at Auckland Airport on his way out of the country. Inside the issue was an article about MP3.com, one of the early music downloading websites. Hocquard decided he should make a similar website for New Zealand artists, but his site would sell music for a small price rather than giving it away.

The arrival of Napster in 1999 saw the major music labels working towards a digital rights management system that they hoped would mean users could download a song to play through specified software without being able to share it. They weren’t interested in supplying their catalogue to Hocquard, as he wanted to sell MP3s without the clunky “Digital Rights Management” software attached. This led him to approach independent artists and labels instead.

“I knew Jubt Avery through bFM and Johne Leach helped out too. Jubt’s job was to approach the New Zealand music artists and convince them to sign up. We spent a lot of time on the internet researching what would be involved. We found a really good web development company in Wellington. They employed a programmer who’d done some work for MP3.com, and with his help we managed to launch the site.”

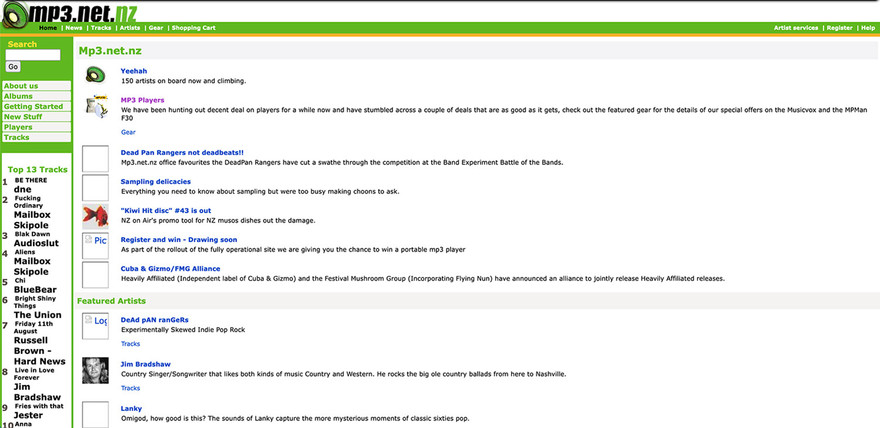

The original MP3.net.nz site in August 2000. The MP3 player advertised had a maximum of 128mb of memory so could only hold around 34 songs.

Hocquard originally named the website MP3.net.nz, a tongue-in-cheek nod to the fact that they were taking inspiration from an illegal website and trying to turn it into a legitimate business. It was soon renamed Amplifier and became a web store that sold downloads, CDs, and other merchandise. It was the physical sales that paid the bills and allowed the site to eventually employ two staff, the longest-serving being Stephen O’Hoy (manager of One Million Dollars) and Richie Setford (solo artist as Bannerman, and singer from Batucada Sound Machine and One Million Dollars).

Richie Setford and Stephen O'Hoy around the time they first started at Amplifier.

Hocquard’s work as a lawyer was increasing and he employed a junior lawyer to assist him before eventually going into a partnership with Tim Riley, who was interested in film and built up that side of the business. Hocquard was now working for most of the big names in local music. This included his childhood heroes Tim Finn and Dave Dobbyn, and he appreciated the chance to work on international deals which increased his knowledge of the industry.

He wasn’t fazed by the experienced international lawyers that sometimes faced him on the other side of the negotiating table.

“I was in my early 30s by then, so I wasn’t just a kid. My background wasn’t only in conveyancing, I’d also done a lot of child-abuse prosecution in London. So there wasn’t a hell of a lot that was going to shock me or intimidate me from a lawyer’s point of view. Everything is a confidence game, because there’s no one there to teach you. You’re learning on the job constantly. At the beginning, I didn’t know what a producer agreement was and I had to learn publishing by reading the most intense books. No one else really understood it, including most publishers …

“I learnt really early on as a lawyer, that if you don’t understand something you need to say ‘I don’t know what this means, you need to explain it to me.’ If you’re trying to bluff your way through and you don’t know what you’re doing, then there’s a high chance you’re going to be fooled or you’re going to get it completely wrong. I can remember the first couple of deals I did, it might take me a week to write a letter that would now take me 20 minutes. Back then, I had to second-guess every line. These days I can look at a contract that’s 40 pages long and I know which 10 points I need to focus on. Whereas at the beginning, I laboured over every paragraph. You’ve got to take a big-picture approach.”

It was through his role as a lawyer that Hocquard became involved with the Rhythm and Vines music festival.

“Hamish Pinkham set up the festival with Andrew Witters. Then these people from the old-boys network in Gisborne tried to wrestle control of it away from them. I was brought down to have a meeting with everyone involved, in the local accountant’s office. I explained to them that it wasn’t going to happen. I gradually got more involved from then on. When they got in the shit financially, I helped them manage their way through that and was chair of the board that ran the event for 10 years. Eventually I helped them sell it to Live Nation.”

Hocquard found that his independence meant he could be more frank when commenting on important issues.

Hocquard found that the independent nature of his work meant he had more freedom than other established people in the music industry to comment on important issues of the day. In 2006, he went on evening news show Close Up to provide a counterpoint to Labour MP Steve Maharey who was announcing the government’s support for Kiwi FM – a radio station that was dedicated to only playing local music. The government had made a deal with the private company Canwest to give them FM frequencies worth $20 million to run the station. However, Hocquard pointed out that Canwest wasn’t bound by contract to keep Kiwi FM going, so he predicted they would let it die a quick death and use their cheaply gained FM frequencies for a more lucrative commercial station. And so it came to pass.

A few years later, the government introduced the Copyright (New Technologies) Amendment Act 2008, which was targeted at reducing illegal downloading. By this stage, music industry revenues had fallen to nearly half of what they were. Nonetheless some commentators criticised the bill for going too far, since it suggested that internet providers could kick customers off their service if they found them illegally downloading content. Hocquard responded by speaking out in favour of the bill.

“The one thing I understood the whole way through was the impact that piracy had on people’s incomes. All of those commentators talking about internet freedom weren’t really acknowledging that aspect of it. They said they were only stealing from the big multinational record companies, but the reality was that if the record companies had signed an artist and someone downloaded their music without buying it then the artist wouldn’t make any money. It’s copyrighted material, so that is stealing. It was getting harder and harder for artists to make any money …

“I also understood enough about the technology to know full well that the internet providers could easily identify who was illegally downloading music, they just chose not to do anything about it. So that Copyright Amendment Act came through and I backed it, even though the act itself was toothless. But at least it was an attempt.”

The early 2010s were a disruptive time within the music industry. Amplifier’s business was slowly being killed by the rise of illegal downloads, but the company started a new website called The Audience to highlight local music. The idea behind it came from Brendan Smyth, the long-serving Music Manager at NZ On Air. Part of Smyth’s aim at the time was to take a “bedroom to boardroom” approach, where he looked for ways to take inexperienced musicians and get them to a stage where they could apply for music funding.

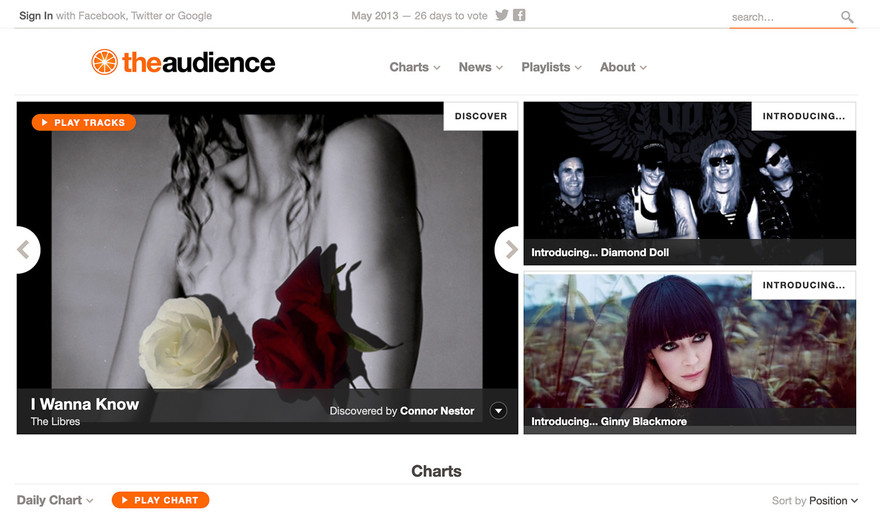

The Audience website

As part of this, he thought that it would be great to have a website that could act as a music discovery tool for listeners to find upcoming artists. The hook would be that the most popular act each month would be given NZ On Air music funding of $10,000 to make a single and a music video. The team at Amplifier created The Audience with the support of NZ On Air and it initially seemed to be working well (for more on The Audience, see From MP3 to Streaming, part 2).

In the end, Hocquard’s team didn’t have time to take the idea further, because Smyth had left NZ On Air and a consultant that was brought in to write their digital strategy decided The Audience should be discontinued. By 2015, both Amplifier and The Audience had come to an end, but Hocquard had plenty to get on with.

Not only was he increasingly busy as a lawyer, but he also co-founded the label and production company Dryden Street. The genesis of this work went back a decade earlier when Hocquard was asked to help arrange the schools tour, which took local bands around local high schools. He ended up funding the tour and bought a bus with a trailer to use for it. Sadly the schools themselves eventually decided the school tours were too much hassle, but they had been a useful promotional endeavour for upcoming acts at the time. One of the bands involved was Goodnight Nurse; Hocquard befriended lead singer Joel Little, and became his lawyer.

Through working with Goodnight Nurse, Hocquard became Joel Little’s lawyer.

Hocquard helped arrange a deal with FMR (Festival Mushroom Records), through Mark “Ash” Ashbridge and Ashley Page, who were key decision makers at the label. However, FMR was bought out by Warner Records and many of the New Zealand artists were lost in the transition. The label got cold feet about releasing Goodnight Nurse’s second album in Australia. Hocquard managed to convince Ashbridge to go ahead with it, which he says gained undying loyalty from Little. Page was frustrated with the way things were going at Warner, so quit and went into management, with Little becoming one of his longest-running clients.

Joel Little then went on to greater success through his collaboration with Lorde, which led to him co-writing a run of billion-streaming tracks for artists such as Taylor Swift, Imagine Dragons, and Khalid. Hocquard remained his lawyer throughout the transition and the pair decided to work together with Page on setting up Dryden Street, a singles-based record label and production company.

They had an immediate hit with Kids of 88 and followed it with breakthroughs by Broods, and Australian act Jared James – all produced initially by Joel Little – as well as Robinson, who achieved an amazing breakthrough after featuring on a major Spotify playlist in the US (‘Nothing to Regret’ has had 128 million Spotify streams to March 2025). The label continues to work with new acts such as Aubrie Mitchell and Max Alias. The management side of the business now is largely producer-focused and the company has staff in LA, Nashville, and London.

The Streaming Era

Hocquard’s business involvement in the streaming era came through connections that stretched back a decade earlier. In 2006, Amplifier had moved into a new area of digital music through becoming an “aggregator” – an intermediary company that supplies a musician’s files to music stores/streaming companies on their behalf. It was difficult to predict how important this work would become in subsequent years and Hocquard had to have his arm twisted to get involved.

“I was approached by Morgan Donoghue. I knew him first as the kid who worked in the Big Day Out office. He went on to EMI and then Vodafone, which is when he got in touch. Vodafone Music launched in New Zealand the week before iTunes and as soon as he made the announcement, every artist in New Zealand contacted him to ask ‘how do I get my music on there?’ So he rang me and said ‘Look, you work with all of them anyway. Can you do it?’ And, this is how stupid I am, I said to him ‘Why in the fuck would I want to do that?’ But he pleaded with me so I agreed to it. So we worked out a deal and went back to the artists, who were all happy that there was finally a way to get their music on there. So that’s how it started.”

Over the next few years, Amplifier worked within a crowded field of aggregators who supplied music primarily to iTunes. Hocquard separated this work into a new company called Digital Rights Management (DRM), which gained a central place in the industry once Spotify arrived. The company name was again a reflection of his sense of humour – he had seen a decade of people complaining about digital rights management, but now Spotify had found a way to make it seamless and suddenly everyone accepted that they would subscribe to access music rather than owning MP3s (or other music files, without digital rights management attached).

Hocquard brought in a set of partners for DRM that he believed would make it into the main independent aggregator in the country. Firstly there was Roger Marbeck and Peter Baker, who ran the distributor Rhythmethod and found success with acts such as Fat Freddy’s Drop. Then there was Vaughan Stebbing, who brought with him the tremendous catalogue of music that the Stebbing family’s various music labels had released over the past few decades.

DRM gradually succeeded in becoming New Zealand’s biggest independent aggregator, though Hocquard recalls it was a struggle at first.

“The formats kept changing across the different platforms: iTunes had one delivery system, while the others were quite different. So quite early on, we went to Believe, who are a massive aggregator based in France. At one point, Stephen King, who is the UK boss, came out here for some talks. Peter and I had dinner with him one night. We arranged to deliver to him, then Believe would deliver to Spotify. We had direct contracts with Apple and Spotify, but because we were so small we couldn’t get deals with some of the other streamers. New Zealand artists complained to us that they couldn’t get on Beatport, which was funny given how little revenue that brought in. Luckily we were members of Merlin – the international association of independent artists – which had deals with those companies, so we made arrangements through them. Our streaming work trundled along for a while without providing too much income, but eventually Covid came, and digital just blew up.”

Ironically, when the first Covid lockdown occurred, and with tour cancellations leading to music releases being put on hold, Hocquard thought the music industry was dead. While he was pondering what his next step should be, he received a phone call from a woman whose son had been approached by a Chinese company. They wanted to buy one of his tracks that was blowing up on TikTok and were offering him US$1500. To him it was a lot of money, but his mum wasn’t sure.

During Covid, Hocquard was called by a woman whose son’s song was blowing up on TikTok.

Hocquard looked into the situation and found that the song was going nuts, so he decided he would need to get involved.

“Normally with a big international thing I would tap into my networks and arrange an introduction to a US or UK lawyer, but with lockdown everywhere I knew that wasn’t an option so I’d have to do it myself. I quickly arranged for him to sign a short-term deal with DRM to protect his position while we worked out a better plan. Within days we were being approached by major labels from the US and the UK. I’d seen plenty of viral hits before and knew that timing was everything. The song was ‘Siren Beat’ by Jawsh 685.

“One of the labels had connected [US singer-songwriter] Jason Derulo with the beat and his management were on the phone, they wanted to buy the beat, but already I could see it was bigger than that. I put them on ice and told the labels to make me their best offers. I had Ashley Page who had a personal relationship with one of the label heads – Ron Perry – from his dealings with Joel and Broods, as well as Nicky Stein who is one of the best entertainment lawyers in the world, so I was able to talk to him about it. It was lockdown so there was no real sense of day or night so I just sat in my home office late at night and got it done.”

The phone calls went back and forth until they had managed to arrange a deal with Columbia – the biggest deal Hocquard had ever done. He was pleased that the advance alone was enough to set up Jawsh for life. Despite the perseverance of Derulo’s team, they hadn’t been able to bully their way past the young man they had originally been dealing with. Instead, they had to deal with Columbia and settled for a royalty. The song went on to be the biggest hit of the US summer and made No.1 in many countries.

Hocquard was overjoyed with the result. “We set it up in a way that Jawsh would be protected and I watched proudly as he went on to buy his family their dream home. It was funny how it all came together, it was like everything I had done over the years suddenly made sense. I understood how the digital thing worked thanks to DRM, I had the legal skills and the international knowledge thanks to working with Ashley, Joel, and Dryden Street and, most importantly, I had people around me I trusted who could help me make this work.”

DRM screenshot

Over this time, DRM became a key player in the New Zealand music industry. Its key point of difference in comparison to overseas-based aggregators was that artists were able to speak directly to staff at the company to get advice on how to supply their work and, in some cases, the best ways to position themselves to get on playlists and improve the performance of their tracks. DRM even started a marketing arm to help artists in this manner.

By 2024, Hocquard saw that the huge amount of music being supplied to Spotify was changing the marketplace. While previously there was the possibility of contacting Spotify’s team in Australia to pitch new music, this was increasingly becoming ineffective.

“It has become very hard now and everyone is promising artists things that I know that they can’t deliver, but they don’t care. Everyone is also cutting their margins to the point where the only way it can work is if you use a bot and you take an absolute mass-market approach. That’s when I decided it was time to get out. There is a margin that you need to make to make it work, and as soon as you start going under that, you’re going to get to the point where you have to reduce your service. I spent so much time and energy making DRM a trusted partner I wasn’t prepared to let DRM make promises which we couldn’t fulfil. It was just time to make a change. We needed a partner with some serious muscle.”

The result was that DRM sold to US distributor/aggregator The Orchard in June 2024. DRM is still run out of the same office in the Auckland suburb of Kingsland with the same staff, but now has an international partner that Hocquard believes can deliver what a small New Zealand independent couldn’t. As far as he was concerned, it was the perfect arrangement. His work as a lawyer continues, but these days he delegates much of the operation to his new legal partner, Joel Tashkoff. Hocquard is still on-hand for long-term clients or more complicated issues.

--