--

If his achievements have been driven by ambition, he keeps it well hidden. He could be talking about himself here: “I don’t think that drive to succeed is common in New Zealand artists, or at least it wasn’t when I was playing. There wasn’t even a belief that success could happen and that to even think it could was somehow unseemly.”

But success came all the same (and if it didn’t, he had a good crack). So some credit must go to the teacher who first realised this six-year-old could sing. Encouraged, Black’s mum didn’t stop there: her boy was quickly into ukulele and guitar, and entered into every music competition within a short drive of their home in Waverley, Dunedin.

His neighbour’s Elvis collection set him on course for his first band, Jailhouse. This was led by another local lad, drummer Barry Blackler (later with The Idles, The Starlings, Jesus and Mary Chain). Blackler’s sisters had musician boyfriends who lent them gear.

Black was only 12 when he played his first gig, a church dance organised by veteran radio host Rev Ewing Stevens. From there it was neighbourhood shows and parties – “we were rock stars at school” – and on to the concert chamber in town to play alongside the professionals.

“There were older bands that we looked up to, we’d watch them to learn chords, so playing ourselves seemed like a natural thing to do. Our teens were spent practising and playing, there wasn’t much else to do. There’s that old line, ‘Oh Dunedin, it’s cold and nothing happens’, but it really was cold. In between songs I’d run my hands under hot water so they’d still work.”

Creative differences stymied Jailhouse. Blackler wanted to play rock, Black was all about Marvin Gaye and Renee Geyer. Black then turned to some some kindred, if much older, spirits, and joined After Dark, a covers band specialising in what they called Space Cabaret. Still at high school, he was making reasonable money while testing his chops on Steely Dan songs.

“Our practice room was next door to The Enemy, we basically shared a wall with them. The guys I played with hated them with a vengeance and they hated us. Well, I guess they did, they never really said so. That was my first experience of the punk thing, and in Dunedin at that time there was a real division between the two scenes.”

After Dark soon morphed into Strictly Blues who played exactly what it said on the tin.

At the same time, some Otago Boys’ High School pupils had begun jamming. First called Static and then Temporary Bliss, they enjoyed a summer of gigging out of a transit van before starting at Otago University.

By the end of their first year they’d recruited Nick Sampson, a student from Taranaki. After turning on to Dexys Midnight Runners’ debut album Searching For The Young Soul Rebels, they added a brass section.

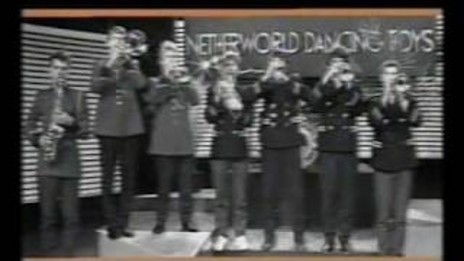

It was trumpet player Alistair Perry who named them Netherworld Dancing Toys: it came from a line in ‘Spin Me Round’ off Roxy Music’s Manifesto album. After a handful of practices they agreed another singer/ guitarist was needed and an advertisement was placed in the local paper.

With Strictly Blues now broken up, Black – in year two of his law degree – saw the ad, and while he wasn’t particularly impressed by their name – “No, it didn’t fit at all. I never knew if it was a good idea or not” – he got in touch.

“We got his reply,” says Sampson, “and the guys were all ‘Ooo, Mal Black’ and I was ‘Mal who?’ They’d all seen Strictly Blues and After Dark who were apparently great.

“Then Mal turned up to a rehearsal and pulled a flash amplifier out of his car and then a flash guitar. I didn’t have an amp so my guitar was plugged into the bass rig. Then he said ‘what do you want to play?’ Someone said ‘Midnight Hour’ and I remember him saying ‘what key?’ ‘Oh, ummm, E?’ Then he started singing and we just looked at each other. So we played some songs, then went to the Robbie Burns for a drink, and that’s how it started.”

“It was a breath of fresh air,” says Black. “The bands I’d played in it were all about covers and being able to play, the idea of writing your own songs was secondary to musicianship.

The Netherworlds wanted to be “big and bright and dance, no shoe gazing.”

“And the Netherworlds knew what we wanted to do from the start: a kind of antithesis to the Flying Nun bands of the time. We wanted to be big and bright and dance, no shoe gazing. We wanted big lights and big sound.”

Their first gig was a private show, The Consummation Party, at the Orphans Hall. “We’d been rehearsing for maybe six or seven months, sold tickets to our friends, put on cheap booze, got about three or four hundred people and had a really good time. The next week we played across the road from the [Oriental] and when they saw the numbers going in, the Ori booked us immediately and we never played to an empty house. We just kicked on.”

Word soon reached Flying Nun’s Roger Shepherd who made a point of seeing them play the Gladstone in Christchurch. “I think he quite liked the music, but he may have liked how many people were there more, so [signing us] was probably partly a commercial decision. Chris Knox was good to us too, he didn’t ever like us and always made sure we knew it, but that didn’t stop him from putting us up in his house.”

Then after a slot at the 1983 Sweetwaters festival near Auckland earned a good review, followed by Radio With Pictures using ‘Change to the Contrary’ (one of Black’s first songs, which used lyrics written by Sampson’s flatmate) as the theme for their festival special, the band hit the national circuit.

Which is where their original plan ran out: “We’d only thought about playing live really, recording may not have happened at all if Roger hadn’t made us an offer. We just thought we’d finish our degrees and see what happened.”

Come 1984 and Virgin Records’ New Zealand office was under pressure to do something local. Marketing manager Annabel Carr headed out to sign a band.

“She looked around,” says Black, “and kind of went, ‘you guys’.”

Now with a decent budget, the NDTs took on producer Nigel Stone from Wellington’s Marmalade Studios, who had experience recording horn bands.

One of his first calls was to bring in drummer Ross Burge, bass player Rob Winch and the Newton Hoons horn section (Chris Green and Mike Russell, plus Rodger Fox). They all feature on the NDTs’ best-selling single, ‘For Today’, which peaked at No.3 on the singles chart in 1985.

“A big part of the reason ‘For Today’ sold so well was that the rhythm section is cooking. It’s not ours. That was a hard decision for Nigel, but we were pretty pragmatic about it. We surrounded ourselves with professionals and it worked.”

Still, success was unexpected.

“We were on tour as that record was taking off, and every now and then Annabel would find out where it was on the charts. Then the crowds started to get bigger, and they started to change, not always in a way that was necessarily for the better.

“So now we were thinking: ‘Oh, this is how it works. Maybe this is what we’re going to do for a while, maybe this is going to be big.’ Then we won all the [New Zealand music] awards and we were ‘What do we do now?’ Everyone was finishing at uni, but some decisions were being made for us, especially when Virgin couldn’t get the record released outside New Zealand. That was the obvious next step.

“I know Nick [Sampson] would have loved to have kept going and made a career out of it, but for me … well, there are musicians who just have to play because that’s who they are, people like Shayne Carter, or Bic and Che; they’re musicians in that way and we weren’t. I know I wasn’t and, apart from Nick, the rest of were ‘Well, that was good.’

“I couldn’t deal with the insecurity of band life anymore either. In a band what you get out of it never equates to what you put in – there’s no kind of cause and effect – and that was too wobbly for me and so when it ended I had no inclination to play with anyone else, none at all.”

Black can’t even remember the band’s last gig: “To be really honest, if we’d left New Zealand and gone up against the top-level soul acts, that would have been a tough ask. I don’t think we were good enough.”

An ex-pop star at 24, Black lined up a job as an entertainment lawyer.

Now an ex-pop star at 24, Black lined up a job as an entertainment lawyer with law firm Russell McVeagh (the band’s lawyers) and aside from a brief reunion in 1989 – resulting in the album Everything Will Be Alright on CBS – that was it for the NDTs.

“I ended up working on all those film partnerships and bloodstock deals. It was 1986 and they were dodgy dealings, but it felt quite glam. I was in Auckland, living in Emily Place in the Brooklyn Apartments and the firm was down in Shortland St, just around the corner from High St and stuff.”

After three years Black, then 28, returned to Dunedin to complete his masters in law and was offered a lectureship. He also ran a music consultancy from his office and, after being brought on board by Straitjacket Fits manager Debbi Gibbs, was soon representing Flying Nun bands (including SJF, The Verlaines and The Chills) looking to release music offshore.

“I didn’t have much of a relationship with all those guys prior to that. We sort of knew each other, but I think on the whole they liked having me as a lawyer because I’d played and I knew their world. There were no real lawyers specialising in that area either, so I learnt fast. After Russell McVeagh, I was reasonably competent and they had this big set of books, they were like the bible of entertainment law contracts and with those I could bluff my way through. Lawyers in that business were kind of hustlers and everyone was using the same bible I was, so it was a dance. They wanted [the bands] and they knew what they wanted to pay. We didn’t get A deals, but they were offered B deals and those go all the way to D so they were serious and piled in a fair bit of money.”

Then the three-year itch struck again and – realising he’d stumbled across a potential career – he returned to Auckland without completing his masters.

He’d already been contacted by Shane Simpson, a Sydney music lawyer who was hoping Black would open a branch of Simpson Solicitors. But after spending some time with Simpson he decided to open an office of his own. Black also travelled to America to door-knock entertainment law firms to hear how the industry was changing. Then he approached Mick Sinclair, an Auckland film lawyer, and the pair established Sinclair Black.

“Everything was evolving and I just happened be around when it started to take off a bit. I started acting for Supergroove – the first local band to sell a serious amount of records – then Shihad and Dave Dobbyn, pretty much everybody then, and those bands, for the first time really, were starting to sell.

“The Netherworlds sold maybe 10 to 12,000 and that was a lot back then. Supergroove sold 60,000 or something and it was just another level. So the momentum was building and New Zealand music was becoming a thing which created something for me to work off. But saying that, it was hard work and I wasn’t getting paid a whole lot because some bands could pay and some couldn’t, I wasn’t too tough on it. But if I [represented] a band, I would try to get them a deal [as he did with the feelers]. I was following the American lawyers I’d met who were very proactive. They acted as gateways into record companies.

“But really it was great to still be part of music and involved with the artists, I felt really strongly about that, and I’d say I had a lot to do with organising accountants and stuff like that, support that didn’t really exist in that band-world before.”

From 1992 to 1996 Black had a hand in most of the deals signed in this country, working on behalf of the labels, and more often he was seated opposite Campbell Smith who had moved into artist representation. Sony at that time were particularly aggressive in the New Zealand market and Black found himself working with them more and more. When Paul Ellis left to join Sony Music Publishing in New York, Black was the obvious replacement.

Now 35, he left Sinclair Black to assume the roles of Sony Director of A&R, Director of Business Affairs, and general manager of their publishing company.

“That was fun, it was nice to be able to influence things a bit more than just being a lawyer, and there was money. Michael Glading was running things, it was all white marble and big boardroom tables. CDs were being introduced and they were living large, but to Michael’s credit he did pour a lot into local A&R.”

Black inherited a roster boasting Dave Dobbyn, Bic Runga and Strawpeople and set about signing Stellar*, Che Fu, Brooke Fraser and Dimmer. “We had a proper roster.”

His one miss was Hayley Westenra: “I didn’t quite understand the music, it wasn’t my thing, but I’m sure some others did. But signing Dimmer, that was a real pleasure. It was nice to be in a position to do that sort of stuff.”

After a few months he attended a music conference in Barcelona and sat in on a session about A&R work within a big label. It became clear that his best move would be to run his own label with its own deal and negotiate a consultancy deal with a major label to cover the rest of his work.

So he became an independent contractor and set up Heart Music with his then-wife, artist Tracey Tawhiao.

“[Heart Music] was driven by Tracey to a large extent to support Māori and Pacific Island music. My thing in those days, I wanted to do a Fugees, I wanted to try and get Danny Haimoana [Dam Native], Teremoana Rapley, DLT, Che Fu, King Kapisi all in the same band. To me, that was like ‘woah, what would that be like’ because they were so fantastic individually. But I couldn’t make it work and they didn’t want to work together. So the next best thing was to try and do that through Sony, and they were keen.

“It didn’t happen, so I ended up signing Che to Sony, and he was as out there as Sony were prepared to go. The 2 B Spacific record worked well, but if I hadn’t been there I don’t think they would have been able to work with him. Che didn’t play the corporate game, he just wasn't interested.

“Sony is designed to sell American music to the world, not to take local artists back.”

“I’d also been trying to sell Bic and Dave overseas through the Sony system, but Sony is designed to sell American music to the world, not to take local artists back. When you try to get a local artist supported you quickly realise Sony are tied up with their own priorities and their own artists, thousands of them.

“So, with Heart, I thought two things: the uniqueness of New Zealanders and those Pacific Island and Māori musicians – they’ve got something no one else has – and that if I could run it independently I could find distribution outlets that wouldn’t mean trying to shove stuff through Sony’s corporate channel. None of those artists could work in the Sony environment anyway – even Tha Feelstyle wouldn’t have been commercial enough.”

But big ideas and idealism only go so far and by the time it folded Heart Music had only managed four (hugely influential) releases. They’d tried and pitched their wares each year at the Midem trade show in Cannes: “We took Danny [Dam Native] once and he was his usual larger-than-life self. He didn’t behave particularly well, but that was kind of cool, everyone soon knew who he was. He was a star, Danny, he could hold a stage like no one else can. But like a lot of those guys, he was self-destructive in a lot of ways. It was hard work.

“It didn’t help that we had no money, we were scraping together to make things work and it took a long time to make records, but that Tha Feelstyle record, that was a piece of genius, it’s beautiful and that was producer Andy Morton [Submariner]. He’s a genius. He worked on Bic Runga, Che Fu and Dimmer, everything, he’s a clever guy.

“But my one true disappointment is that Tha Feelstyle [a joint venture on the label Can’t Stop Music through Festival] didn’t do better.”

In retrospect he thinks they took on too much: “We needed a lot more money, then I could have bought my way through and organised everything. But even while Tracey and I were trying to do this, I was still working full time at Sony and we had little kids. There was only so much time to give and it needed way more care and attention with the added frustration that you couldn’t particularly rely on the artists to do their part.

“But, you know, Emma [Paki] and Danny have lived hard lives so they don’t trust easily. So [we] gave it a crack and had a cool thing going on but never quite pulled it off then. At the same time, Tracey and I sort of imploded and that didn’t help, but still I love those records and I’m proud of that period of time even though I feel like we didn’t do enough. Maybe should have gone all in? I’m not sure, I don’t know that it would have ended any differently.”

If a change was needed it was fast arriving when Les Mills CEO, Phillip Mills, called looking for help with a complex and potentially lucrative problem.

Les Mills were selling a range of exercise programmes to about 100 countries around the world and needed to licence the music used to drive each class.

In terms of music law, it was groundbreaking stuff: “They’d tried going through American lawyers but no one could work out how to secure worldwide music licences. It was an amazing challenge and they were kind of landmark deals in a way. I got lucky on that stuff I think, so Phil said if you can do that you can have a chunk [of the resulting income].”

In his final great bit of A&Ring, Black – who was still working for Sony – contracted Joost Langeveld (Strawpeople, NRA, Greg Johnson et al), Chris van de Geer (Second Child, Stellar*), and Andrew Maclaren (Stellar*). In turn, they created Big Pop, who continue to record huge amounts of music for Les Mills for worldwide distribution. Big Pop are perhaps the country’s most prolific group and almost no one has heard of them.

Les Mills became a huge project for Black: he circled the world about five times a year, until he stepped down in 2016, but not before setting up a joint venture which provides something of a Netflix-type service for people to exercise to at home.

In the meantime – if nothing else he’s always open to new opportunities – he had also become co-manager of Neil Finn and Crowded House.

Black and Finn had met on a flight out of Los Angeles with Finn saying how he wanted to replace his London management with something more local. But three jobs wasn’t going to work, so Black left Sony and brought in Mike Bradshaw – who had been running Sony – as his co-manager.

Then Crowded House reformed, recorded Intriguer and undertook a world tour before Finn released two solo records and the Pajama Club LP.

“That was an incredible experience for me and a really transitional time for him,” says Black. “Quite a delicate time really, he was navigating his way through a mid-career sort of thing – he wasn’t old enough to be iconic – with a young family.”

Their association lasted five years. “It was cool because he encouraged us to do things a bit differently.”

One of Black’s first tasks was to consolidate Finn’s material that had become spread over a range of record companies and publishers and find new ways to market and distribute it.

“Neil would be successful at whatever he does because he’s seriously intelligent and driven. He really works so hard and so efficiently, and if I compare that to the Heart Music I understand why that was never going to happen. That was the insight he gave me: ‘Oh I get it.’ Then I started to see other bands Neil knew like Radiohead and realised that in all those bands there’s always at least one person success doesn’t just happen for – that drive and functionality is there – and I think that goes without exception.”

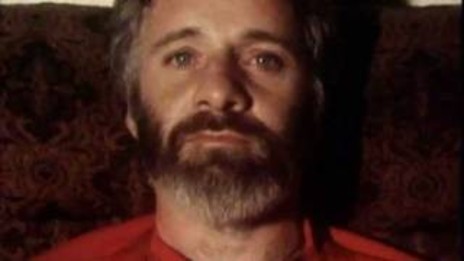

On April 1, 2018, and after a music career spanning five decades, Malcolm Black retired to enjoy his new family. Six months later he was diagnosed with cancer.

But that hasn’t meant an end to music, he’s playing bass and recording with his original bandmate Barry Blackler and NDT cohort Nick Sampson. They began as Grecian 2000 but the name is still up for debate.

Black is also getting classical piano lessons from composer, arranger and vocalist, Victoria Kelly.

He was elected as New Zealand writer/director of APRA AMCOS, succeeding Don McGlashan, and in 2019 was made an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit.

Black is a founding trustee of the New Zealand Music Foundation, which raises money for musicians in need, and set up a company with Philippa Boyens (Lord of the Rings etc) which represented directors, key artists and film composers in the film industry. “We started that in about 1997 and it ran for a couple of years.”

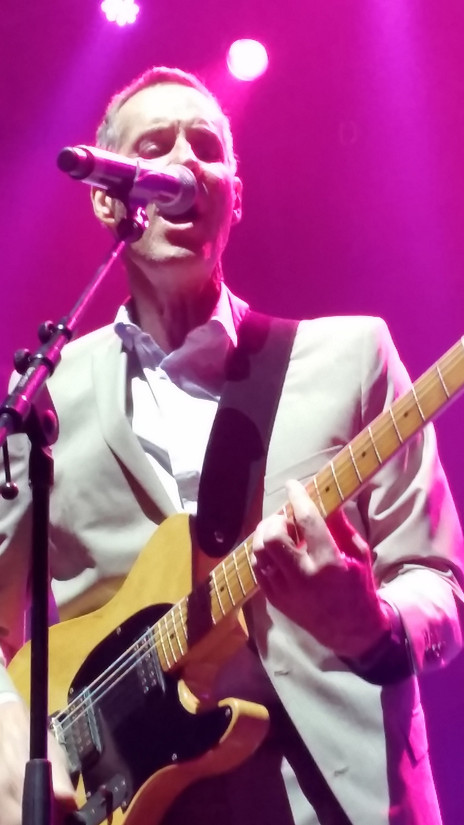

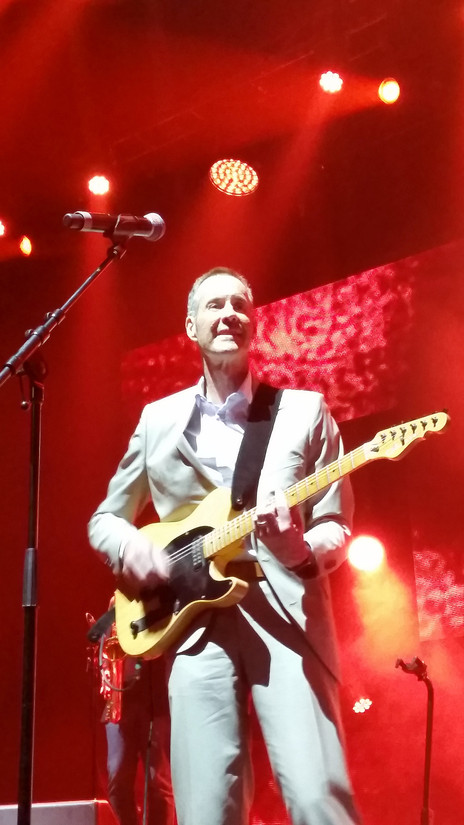

In 2018, The Netherworld Dancing Toys made a surprise appearance to close the Silver Scroll awards: “I was asked if I could close the show and because of my health I was ‘Oh, dunno.’ I couldn’t guarantee how I’d be, so they kept it a complete secret. But that was cool.”

But what have been Black’s highlights?

“As a lawyer, that whole Flying Nun thing with the American labels. It felt like being in the international market and flying the flag with New Zealand product. The music was exploding, the substance was there, and the bands were really good, but looking back what they didn’t have was that Neil Finn belief or killer instinct or facility to hold it all together.

“For me, the Straitjacket Fits break-up [Andrew Brough’s departure] was a tragedy.”

“For me, the Straitjacket Fits break-up [Andrew Brough’s departure] was a tragedy because the vibe of the band changed and it stopped the momentum. You only get one chance where the perfect world has formed and they were in that position.

“Then working with Bic and Che and Shayne. Bic’s Beautiful Collision and travelling in Europe and the US with that record. She’s the real deal Bic, no question. The same with Che and Shayne and Brooke Fraser, so that was a really cool time. But they didn’t have the killer instinct. Brooke probably did and she took it further.

“I don’t know what it is, I wonder if it’s too comfortable here. You can get pretty successful really quickly so you don’t necessarily do the grunt work. That’s what I found with [the Netherworlds]. Within a couple of years, we’d become successful, but hadn’t really put in the hard yards or understood what the business was. We couldn’t even imagine that we could get that big and started out with that in mind. I guess we weren’t ambitious enough.”

Maybe so, but if Malcolm Black’s life in music teaches us anything it’s that there are many ways to have an impact in the industry. In his own ever-adaptable way, he’s just continued churning out the hits.

–

Malcolm Black's album Songs For The Family was issued posthumously on 10 May 2021, the second anniversary of his death.