Cover artwork for Mark de Clive-Lowe's 2019 album Heritage II, released on Ropeadope Records and Mashibeats. Artwork by Tokio Aoyama.

The music scene in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland was always going to be too small for an ambitious musician like Mark de Clive-Lowe. He would sometimes find snide comments being made about him by music writers who criticised him for his drive.

“In the mid 90s, I was definitely seen as a hustler, but I figured if I didn’t do it myself then no one was gonna do it for me. In those days it was seen as a bad thing, but nowadays if you’re not hustling you don’t exist.”

Mark de Clive-Lowe at the 1999 APRA Silver Scrolls

De Clive-Lowe’s career has been in continual motion ever since – from the jazz clubs on Auckland’s High Street to the hottest dance music spots in London, then over a decade breaking into the US scene while based in Los Angeles. More recently, he moved back to his mother’s homeland of Japan. Along the way, there have been dozens of releases, whether studio recordings, live sessions, or remixes – often with the hottest artists of the moment, whether they were electronic/dance music producers or jazz players. This wealth of work made it hard to cover it with any depth on his AudioCulture page, so this interview fills in some gaps while also trying to give a picture of what it’s like being a New Zealand musician working on the world stage.

--

Mark de Clive-Lowe

What first got you started as a live musician?

The big turning point for me was at school. I was 14 and, up to that point, most of the people around me had been into guitar music that didn’t really connect with me. One day, a friend came up to me with their Walkman and put the headphones on me – it was the first Guy album with Teddy Riley’s production – early new jack swing. It just blew my mind. So I bought a drum machine, a keyboard, and a sequencer and jumped into trying to make music like that. I lived near Selwyn College and entered a talent quest they were holding using a one-man band setup. At the same time, at my own school [Auckland Grammar] I was friends with Zane Lowe and Rob Salmon [Urban Disturbance]. We’d play each other our demo tapes.

Mark de Clive-Lowe in 1981 - from his personal collection

You started playing piano from age four, but did you do formal training in jazz?

My teacher taught me classical music, but when he realised I wanted to play jazz he tried to teach me. He really wasn’t equipped to teach jazz, but he tried. I was into hip hop and RnB for my early high school years, then woke up one morning I was like “all these loops and samples are bullshit”. So I sold all my gear – ironic at this point for sure. Then I just had my piano, a Miles record, a Herbie record and that was it. Over time, I’ve had these extreme pendulum swings between things that have all ended up feeding into my music.

Berklee College of Music is a very prestigious Boston music school, so how did you manage to get accepted given your limited formal training? Were you playing live a lot?

I did my last year of high school in Japan. There were some 60 jazz clubs in Tokyo then and my host dad was a Buddhist priest who happened to be a total jazz nut. When I found that out, we went out to jazz clubs all the time and I got to know a lot of musicians, so I started playing there. I came back and formed a quartet with Jason Jones playing sax and Matt Fields playing bass.

How did there end up being four of you attending Berklee around the same time? There was you, Jason Jones, Greg Tuohey, and Matt Penman.

From 1992 to 1993, we all got to know each other. I mean, how many 18-year-old guys are listening to obscure improvised acoustic jazz music? Meeting at places like the London Bar we started playing together. We all felt like there wasn’t enough here, that we needed to go somewhere else. Where do we go? America. How to get to America? Let’s all go to Berklee. We applied and all got different levels of scholarship around the same time. Greg and Matt went from there to New York, while me and Jason came back.

Jazz in The Present Tense in 1996: Richard Hammond, Jason Jones and Mark de Clive-Lowe. Drummer Steve Hass is out of the picture. - Simon Grigg collection

You started Jazz In The Present Tense with Jason and launched the label Tap with Andrew Dubber to release it. How did you end up having US musicians in that band?

When it came time to tour, I wanted to have the best players possible, so I called a couple of our friends from Berklee. The school actually sponsored that tour and the songs we played became the record. Though these days I pretty much bury that album. I was so young and really had no formed sense of musical identity.

Mark de Clive-Lowe recording in Auckland, mid-1990s, as part of the Tap Records collective - Photo by Andrew Dubber

You moved from jazz to club music, which is not uncommon. There’s other cases like the musicians behind Fat Freddy’s Drop or Yoko-Zuna who had jazz training behind them. Why do you think jazz provides such a great basis for moving into other styles of music?

When you cover all the harmonic and rhythmic possibilities as well as learning to improvise so you can spontaneously play with other people then that sets you up great. I mean, if you were a chef and you knew every combination of spices and herbs that tasted great together then you’d be able to prepare any kind of meal.

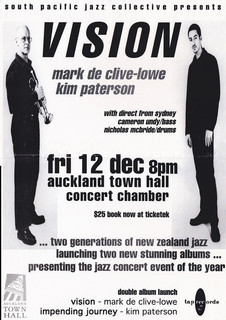

Mark de Clive-Lowe and Kim Paterson, Auckland Town Hall Concert Chamer, 12 December 1997. - Kim Paterson collection

Was taking over Nathan Haines’ band The Enforcers’ slot – at Cause Celebre on Auckland’s High Street – a major turning point?

I feel like I personally had so many major turning points. Cause Celebre was magic. I was growing up amongst serious musicians and Cause Celebre was always more about just having fun. I distinctly remember playing on the grand piano at the Town Hall with Kim Paterson in 1997 and mid-gig thinking to myself, “why am I taking this serious music so seriously, when I could take that fun thing I’m doing at Cause Celebre a little more seriously?” That was a turning point for sure. Then hearing club music that I related to. When I heard jungle I loved how musical it was, whereas I hadn’t been so interested in acid house which had been flavour of the day until then.

There were some other transitional spaces like Deschlers [cocktail bar] where you could play standard jazz or incorporate more modern elements.

Frances Mahoney owned and ran Deschler’s. I was the first musician to play there – I was living on High Street when it first opened, then it became a regular gig. It was cool because it was a perfect spot for people to pre-game before going out elsewhere. Frances let us play whatever we wanted to do: it was a bar before it was a venue, so we really had to work out how to play in that kind of environment keeping it both entertaining and fun as players.

In 1998, you received funding through the NZ Young Achievers Award. As a jazz fan, anyone would’ve predicted that you’d go to New York, London, Paris, and Tokyo – but you also headed over to Cuba.

The whole goal of my life up until that point was go to New York and play with the jazz legends who were still alive and performing – like Art Blakey and Betty Carter. But one of the most inspiring parts of that trip was being in Havana and spending time with Chucho Valdez and other great Cuban musicians. Then being in London and kicking it with Nathan [Haines] and falling into the club scene. That’s when I really moved away from the straight-ahead jazz thing. I arrived in New York with a new MO and did a session with Joe Claussell for a remix he was working on. I remember going in and he said – oh this is François, he’s engineering. It was a great session and afterwards, it was early ’98, I thought I’d look up the engineer on the internet and it turned out it was François Kevorkian, the legendary music producer. Those kinds of experiences were just so eye opening and I really saw how I could contribute to the music as well as learn from it. That wasn’t as clear with jazz. For me at that time, jazz felt more gate-kept.

Mark de Clive-Lowe performing in 1997 at the Manifesto Wine Cellar, Auckland with Kevin Haines, Phil Collings and Nathan Haines. - Mark de Clive-Lowe collection

It seems as if quite a few musicians from a jazz background found a new way forward through experimenting with samples – creating that broken beat sound and cutting up the rhythm in a hip hop fashion. There was a certain movement within dance music – and with innovators like J Dilla within hip hop. It felt like it was just as influential on people from the next generation like Jeremy Toy or Julien Dyne. There was obviously something freeing about improvising around cut-up rhythms. Whether it was making something danceable or making a more syncopated, angular beat.

It took a while to evolve to the point it’s at now. When I first brought in an MPC [MIDI equipment for sampling and sequencing] to use with the band, I had so many musicians giving me the side-eye. Jazzers were saying “that’s not jazz!” So for a while I was in a no-man’s land, before jazz-hybridity as it’s grown to now became more widespread.

Mark de Clive-Lowe - Farah Sosa

Cause Celebre really did feel ahead of its time in that way and had something that wasn’t necessarily going on overseas, partly because Auckland was so small that people from different musical backgrounds were forced to work together.

Totally man. That’s where we all got to know each other – DJs, MCs, and musicians. A similar scene was happening in New York with Giant Step, in London with Straight No Chaser and undoubtedly other parts of the world too, but you had to know where to find it.

Around the turn of the century, you moved to London. How did you make a living over there? You did have a deal with the jazz wing of Universal Records, did that help?

The Universal deal definitely didn’t provide enough income to live off, but it provided me with great exposure and opportunity. I’d be out and playing in Europe every weekend. I was also doing a lot of studio sessions, remixes, and production work. That, and a modest publishing deal, gave me enough to live off.

It feels like dance music culture thrives on finding interesting underground acts, in the same way that a jazz fanatic might be willing to search out some obscure artist. So while a rock festival might just want the big names, sometimes a dance festival might bring in someone more unknown if they are doing something fresh.

Exactly. It’s like the Detroit Electronic Music Festival which used to be called DEMF. I remember in 2001 the artistic director was Carl Craig, and he invited me to play the main stage after hearing my album Six Degrees. So that’s just a case of one person finding a record that they like and having the opportunity to get that person from across the Atlantic to perform. It’s almost like the DJ that has got the deep cut that nobody else knows about – crate diggers!

Mark de Clive-Lowe live remixing

It wasn’t such an online world in that era, so you must have always felt like people back home had no idea that you and Nathan were at the forefront of that scene in London and were able to pack out different clubs every weekend.

Yes, 100%. It was a bit weird. When I got signed to Universal, there was some press in New Zealand in the classic Kiwi style of “local boy does good”, but you definitely felt the tall poppy attitude. I don’t really understand why there isn’t more celebration across the board of every musician who is doing well overseas. I may have left New Zealand a long time ago but have always proudly represented as a Kiwi.

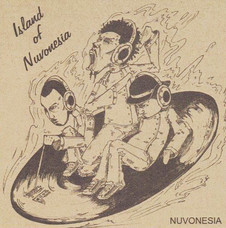

Nuvonesia - Island of Nuvonesia with Imon Star, Manuel Bundy, Mark de Clive-Lowe (Kog Transmissions, 2000)

Was your Nuvonesia album an attempt to reconnect with the scene back in New Zealand?

Me and Manuel [Bundy] had been collaborating a lot over the years – a lot of remixes, my album Six Degrees, and of course the Cause Celebre gigs even before all that. I had a gig with him on Beresford Street and Manuel said there was this MC we have to get on board. That turned out to be Imon Star. He absolutely killed it, so I invited him to join us in the studio the next day. We went into RNZ’s Helen Young studio where – I’ve been accused of fabricating the mythology of this – but it really was a four-hour session, start to finish. We just hit record and there’s the album. Then Tiki [Taane] came in a few days later and did a live mix in one pass. I love the idea of friendships and genuine personal relationships as the vehicle and foundation for music. That’s always been part of my mandate.

Your next albums Tides Arising and Journey 2 The Light felt like a natural progression of what you were doing in London. Renegades had some of the same vocalists, but also seemed to reflect the fact that you’d moved to LA.

Each album is a documentation of each moment for sure. Tides was me trying to prove my mettle as a producer – the aim was to create the music I wanted to hear when I turned on the radio in a parallel universe. Journey 2 the Light was me trying to make a jazz record combined with everything I loved about broken-beat club music. In hindsight, I wasn’t quite ready to fully realise that concept. I finally achieved it though with Church (2014), which was another seven years later.

It felt like you had to find your own way back to jazz?

I barely played the acoustic piano in my 10 years in London. Producers would be like – let’s have piano on this track. And I’d decline, insisting on Rhodes or a synth. They all interface through a physical keyboard the same way, but piano is just a different instrument. Then in LA, I reconnected with piano in a big way. Renegades was half-completed when I moved across the Atlantic, so it became a documentation of the transition. Sheila E, Nia Andrews, and Miguel Atwood-Ferguson were all new connections thanks to moving to LA. The move to LA was actually due to a breakup and my son’s mother and I wanting to be able to raise our son in the same city as each other. I’d always wanted to be in New York, but ironically LA turned out [to be] the right location for me. After 10 years in London, to be back next to the Pacific, with this amazing weather and somewhere everyone seems happier, it actually suited me really well.

You did find a different way to connect with jazz through the Take The Space Trane (2013) album. You did it with the Rotterdam Jazz Orchestra, but it’s clear it’s not going to be a regular big band album given that it starts with such an upfront synth line and electronic beat.

Take The Space Trane is from a live recording. I was playing an improv festival in Holland, and a trumpet player came up to me afterwards and asked me if I wanted to play with his big band. It was something like, “are you free on this date in two years’ time?” So we recorded the shows and that became the record. I do remember during the shows there were some people walking out – “this isn’t big band music!” – which I love. It proves that there’s something unexpected or challenging going on.

That’s where the Church project got started?

I started Church with Nia Andrews, an amazingly gifted LA singer songwriter. We had a slot at a venue called Angels on Sundays once a month and she was like “oh, it’s got to be called Church”. My idea was to document my journey through music from jazz to club music, soundtracking that over one night. It gradually became this modular, revolving door session which took place monthly in both LA and New York. In New York, Nate Smith was the first drummer in the band and the regular bass player was Mark Kelly who plays with The Roots. Loads of horn players would come through, and vocalists. Having people taking part like trombonist Robin Eubanks, rapper Jean Grae, and Questlove DJing was super cool. Just having people I’ve always respected, giving props to what I was trying to do, that was very special. It was the perfect way for me to integrate and collaborate with musicians in both LA and New York too. Eventually I wanted to document the relationship that I’d formed with these great musicians on record. The album was very much about that intersection between jazz and club music, but in a more balanced way than Journey 2 The Light had been.

Mark de Clive-Lowe with Nia Andrews in 2014.

Meanwhile, during the years since you’d been at Berklee together, Matt Penman and Greg Tuohey both created sustainable careers in music for themselves. Though most people in New Zealand probably weren’t aware of their progress. Matt has played with Aaron Parks in the past and now Greg Tuohey is a regular member of his group; there was a feature article on the band in Downbeat magazine.

All of us have been grafting away the whole time. You have someone like Greg Johnson, a Kiwi music legend, whose name might not even be known now to that next generation of kids back in New Zealand, but he’s in the US working all the time, doing his thing. Matt and Greg [Tuohey] have spent the whole time playing and evolving with some of the greatest musicians alive, they’re working at the highest level possible. Sometimes the public doesn’t realise how consistently we all create and work if it doesn’t have a big PR push behind it – it’s the same thing in LA when Kamasi Washington blew up. He’d been around and playing at an extraordinary level for 15 years before the global audience got to hear of him.

Mark de Clive-Lowe with Kamasi Washington in 2015. - Farah Sosa

Kamasi played at your Church events?

Yes, he used to come through with his horn before I even knew who he was. Nia would tell me, “That’s Kamasi, he’s incredible, you should ask him if he wants to play”. And so it was! It’s always great to see everyone you know blossom and become recognised. I just played with a Korean drummer who’s in New York – Jongkuk Kim – who has both played with Matt and is now in Aaron Park’s Little Big band with Greg. He found it so funny when he learnt we are all friends from New Zealand. Knowing all three of us separately, he was like “man, I just want to get you all together in a room and just watch how you kind of interact with each other!”

Your releases over the next couple of years seemed to just be catching up on what you’d done before. There was the Church Remixed (2015) album which included a track with Myele Manzanza. Then there was the Leaving This Planet (2016) collection of B-sides. At the same time, the remixes you did for Fania Records of Latin music from their collection. So you’ve always kept moving forward with new albums, but I’m guessing that your main income over your career has always come from playing live rather than albums?

Yeah. Up until a pandemic, I’d been on the road for 22 years, non-stop. Financially, publishing is part of the picture, studio work is part of the picture and so is my remix work. But yeah – if we did a revenue pie chart, live shows would be the biggest slice.

A couple of years prior to the pandemic you explored your Japanese side through the Heritage pair of albums.

Tracking all the way back, growing up in Auckland there were always Japanese kids’ songs, nursery rhymes, and folk songs that my mother would teach me. The language was always spoken in the house because my Kiwi dad was also bilingual.

Then you did the last year of high school in Japan?

Yeah, that really helped me solidify my foundation in the language. Then I started touring Japan from 1996. I’d always go once a year and play trio gigs with a regular Japanese rhythm section. We’d play the New Zealand embassy every year and I remember my mother would say “well, if you’re gonna play in Japan, you have to play some Japanese music.” Honestly at that age, I didn’t really want to do it, but she insisted. So I would find a traditional Japanese melody and just create what I thought was a hip arrangement – make it sound like Ahmad Jamal or something without having a real connection with the source material. Over the subsequent years, there would be these little moments where I would tap into a Japanese theme. The last track on Six Degrees is called ‘Motherland’ and my first trio record First Thoughts has an arrangement of the folk song ‘Sakura Sakura’.

Then in the late 2010s, I found I was feeling drawn to Japan on a very personal level. I felt a connection I hadn’t really felt before, driven more than anything by a search for belonging and identity: home. Even though I was raised in New Zealand, I hadn’t been back that often since leaving in the late 90s and there was something about Japan calling me there – I just felt so connected to it through family and an intuitive personal resonance.

Yeah, I think sometimes you don’t always realise how culture can come through in the way a parent raises you, even if it’s a different country than their homeland.

The house I grew up in was literally my dad’s own little slice of Japan in Auckland! There’s an organisation in LA called Grand Performances who do big outdoor summer shows every year. I’d always wanted to do a project deep-diving into my Japanese side, and in 2017 they commissioned me to create a live show which I called Mirai no Rekishi – History of the Future. I wrote two sets of music for it for my LA jazz group, then I brought in a koto player, a taiko player, and a shinobue flute player. We also had Shing02, a great Japanese rapper who collaborated with the late great Nujabes a lot.

It was interesting, because I’d never felt so much personal satisfaction after a show before. It felt like I wasn’t trying to play someone else’s music or history. This was honest. In a straight-ahead jazz setting, the history weighs so heavily on the music – it’s almost like you’re in competition with the past. Similarly, with a club gig my points of reference are very clear. I might think “I love this type of house music, so I’m going to make something in that vein.” But in this context, it was my own life story – undeniably personal, so it really was a special moment. That material became the foundation of the two Heritage albums, which were recorded a year and a half later, along with some new compositions. Every track has a story behind it, so whenever I performed those records, I’d share those stories with the audience. I remember right before the first Heritage album came out, I had insecurity around it because I’d never released something this personal before, and it was more subtle than any of my previous work. I wasn’t sure how people would receive it, but it really went over well. After the concerts, people would share how much they resonated with the ancestry and heritage themes, irrespective of their individual cultural backgrounds. The idea of engaging with your ancestry and your roots is a conversation which isn’t always as public as it could be. Audiences at the shows in LA were really engaged with it, especially elders, sharing that they felt so many points of resonance with those stories. It’s cool to realise that no matter how specific our personal story is, there is a universality to it. That was exciting and opened up a whole new avenue of possibility for me.

Ronin Arkestra, the Japanese-NZ jazz collective led by Mark De Clive-Lowe. Their debut release was the First Meeting EP in 2019.

After that, you started a band in Japan.

Ronin Arkestra was a reaction to Heritage, almost a flipside of the coin. I’d created Heritage with my LA band, so then I wanted to do something else with Japanese musicians, feeling like it would provide a more complete picture of my whole personal narrative. Ronin Arkestra was me pulling together my favourite Tokyo musicians and seeing what that would sound like. The album Sonkei (2019) was actually themed around an anime called Samurai Champloo. These two renegade samurai and a girl are on a quest to find “the samurai who smells like sunflowers”. So the album cover shows a woodblock print of a sunflower and every track title is the name of an episode of the show. The album came out right before the pandemic, so we only just finally played our first live show this year [2024].

You have had quite a productive period since then. You did the collaborative project Dreamweavers (2020) with Andrea Lombardini (bass) and Tommaso Cappellato (drums) and then there was the album, Freedom – Celebrating the Music of Pharaoh Sanders (2022). It seems like Hotel San Claudio (2023) was particularly popular with your audience.

Hotel San Claudio was another collaboration story. Shigeto is a Detroit based drummer, DJ, and producer. He’s a second-generation Japanese-American, and we connected when I was playing shows in Detroit. Then a festival in Italy heard that we’d played together and asked us to come over, but I thought we needed a third element to the band. At that time, Melanie Charles wasn’t that [well] known, though her acclaim has grown since then and the festival was open to the idea. So we went to Italy and had a week together to create the show for the festival. We stayed in Hotel San Claudio and the whole week, it was really all about the hang. In classic Italian style we’d have four-hour lunches and spend a lot of that time talking about what we’d eat for dinner! That was the hang, and the music was almost a byproduct of that and our friendship. Soon after we decided we should document that through an album and tour it.

Mark de Clive-Lowe on stage with Melanie Charles and Shigeto in Italy, 2019. - Mark de Clive-Lowe collection

More recently, you’ve researched your dad’s history?

It always seemed so obvious and natural to me to explore my Japanese side. Japan’s so evocative, and I’ve always loved it. It didn’t seem as obvious – or enticing – to me to look at my father’s side. It was only when I was awarded a research fellowship in 2023 that I spent four months in Japan looking into my dad’s time there. He spent 20 years there in the 50s and 60s – he moved to Hiroshima in 1953, just eight years after the nuclear bomb had been dropped. Digging into his experiences and looking at things through his lens was an amazing way to discover a new focus and spark an interest for me in his side of the family. Prior to that, I’d pretty much ignored the white side of the family. It always felt like it might be problematic on a systemic level – small things like the entire history of colonialism. But we can’t deny our roots and embracing that has opened up so many questions and so much inspiration for me.

How did that translate into music?

I’m still finding out the answer to that. My next album is – for want of a better description – an ambient synth-jazz record. It’s all multi-tracked synths, Rhodes and a Yamaha electric piano. There’s no rhythm, no loops, no beats, and no one else. Just the keyboards with some field recordings I captured in Japan. It’s themed around, not so much my dad’s time in Japan, more how my relationship with him healed through the process of discovering his journey. He died 13 years ago and I didn’t necessarily get along with him the best when he was alive. However, I found connection with his younger self through his letters, photos, and archives from over 70 years ago and, through that process, fell in love with my father. It was the most beautiful, cathartic and healing feeling.

Mark de Clive-Lowe on stage with Burniss Travis, Nate Smith and Jaleel Shaw for the launch of Live at the Blue Whale. Joe's Pub, New York City, 2017. - Mark de Clive-Lowe collection

The trend of New Zealand musicians from a jazz background going overseas and doing well – without perhaps the full knowledge of people back home – continues with Myele Manzanza. You and Matt Penman have both worked with him?

I remember when Matt and I were in LA and went to see Electric Wire Hustle play a show. We were at the bar with Myele and laughed about how we had the makings of a dope trio. We’ve never played together in the end, but Myele really is fantastic. Matt’s recorded with him and I’m on a couple of tracks on his album One and then when he recorded OnePointOne (2016) live in LA, I was on piano for that. Then I played on a record he did for Theo Parrish’s Signature Sounds [‘Love Is War For Miles’]. Those records might actually be the most piano I’ve played on a record since my pre-Six Degrees 90s NZ albums. It’s been great to see Myele explore beyond New Zealand and it’s exciting to see what more he’s going to do in London and beyond.

He has that late-night slot at Ronnie Scott’s, which is prestigious, so it does feel like a similar situation where he is working at a high level like you are, but without always getting that recognised at home?

Definitely. I guess to a certain extent with New Zealand audiences, we’re out of sight, out of mind but, for example, Myele just played on Ron Trent’s live band tour and that’s legendary stuff. Similarly for me, a couple months ago I did a collaborative project in LA with Moodymann. We performed together for Dilla’s House – a house music tribute to J Dilla. It’s not like that’s my calling card, but for sure there’s always something happening that I know people at home would love if they only knew about it. I spent over a decade playing with Harvey Mason’s. He’s a drum god, I grew up listening to him on Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters album and so many others. For me these things are really huge and pivotal moments. Ultimately, whether music fans in New Zealand know about those moments isn’t vital – but in the business of music, the industry of it, it’s always nice to know your efforts are reaching people.

--