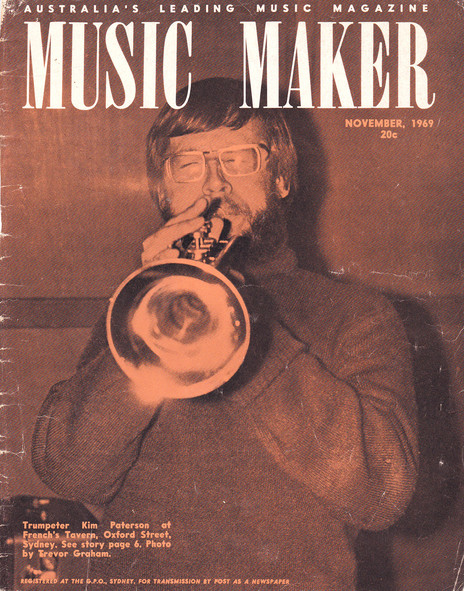

Kim Paterson

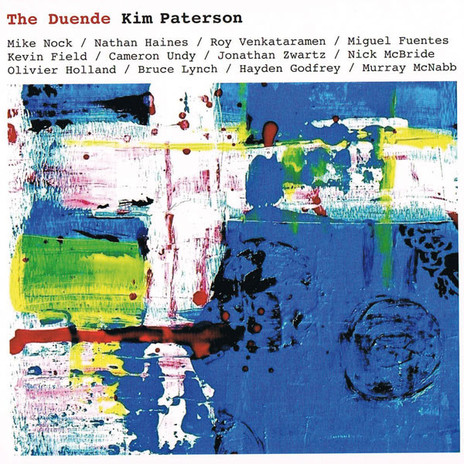

In 2012, when the album The Duende by multi-instrumentalist Kim Paterson was released, he was widely acknowledged as one of the senior statesmen in New Zealand jazz. Yet his catalogue of solo albums was alarmingly small, especially given he had been a mainstay of many acclaimed bands and excellent recordings by others for over four decades.

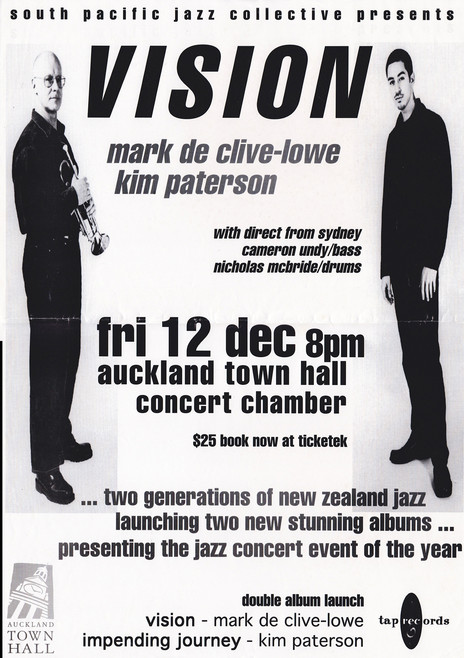

In fact, The Duende was only his second album as leader, the other being his debut Impending Journey in 1997 on the short-lived TAP Records (run by Mark de Clive-Lowe and Andrew Dubber).

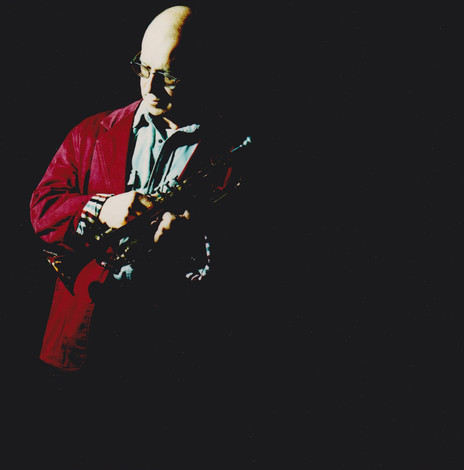

Kim Paterson in the Red Bull studio.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

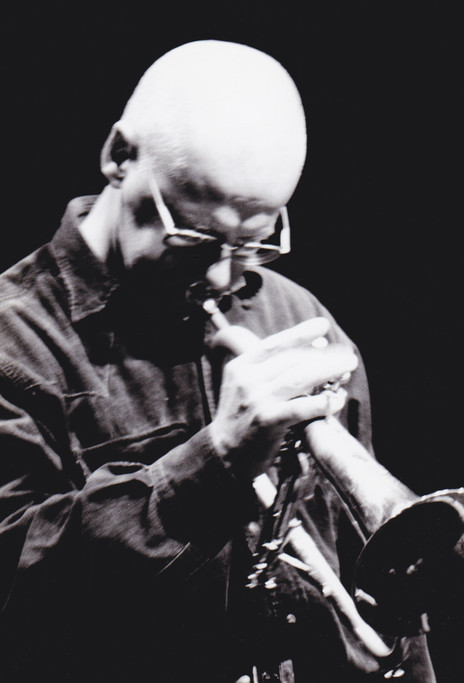

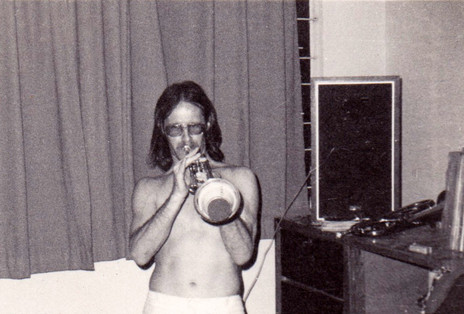

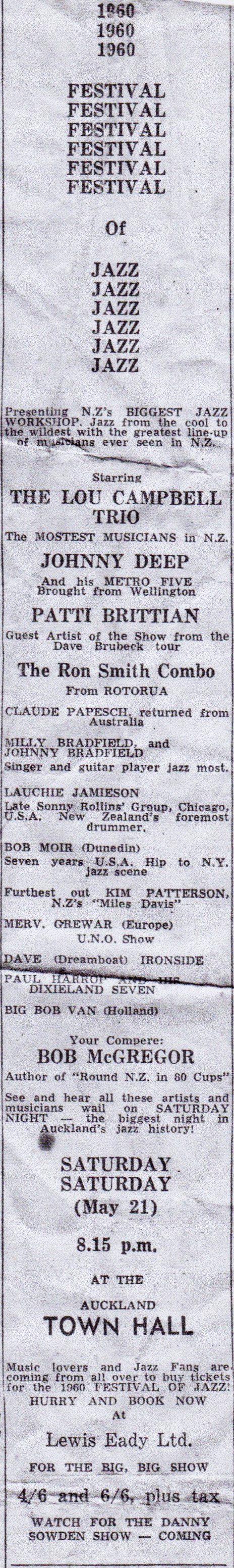

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

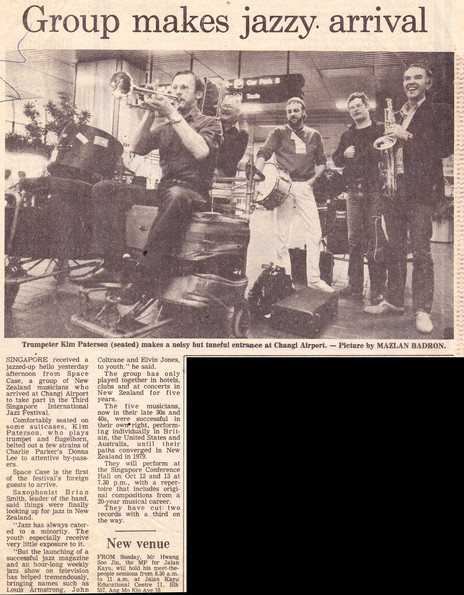

Space Case reviewed in the Singapore Monitor, 1984.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

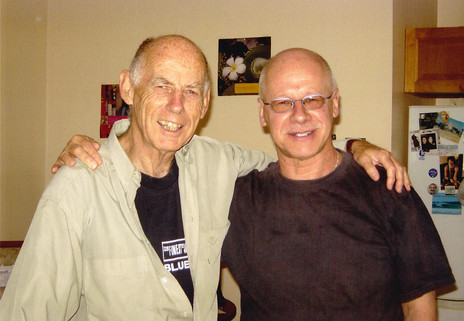

Mike Nock and Kim Paterson

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

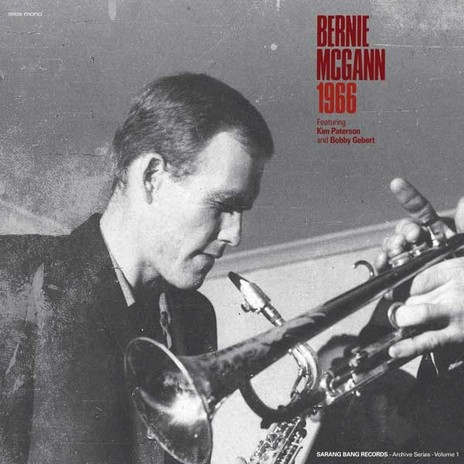

Australian saxophonist Bernie McGann with New Zealanders Kim Paterson and Andy Brown in previously unreleased recordings from 1966. Issued on double vinyl in November 2014.

Space Case.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

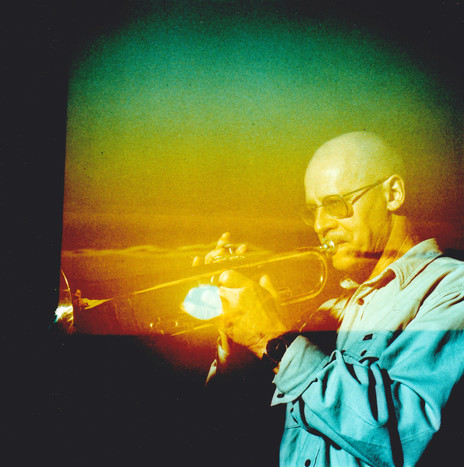

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

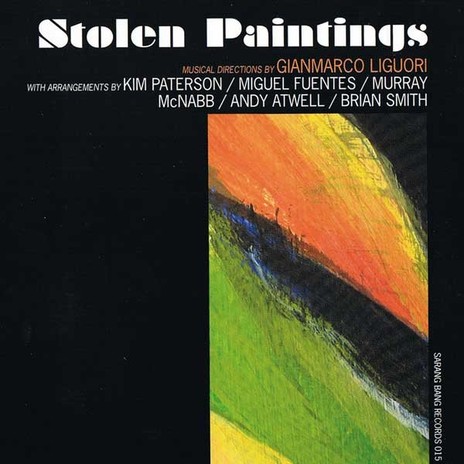

Gianmarco Liguori's 2007 solo album Stolen Paintings featured a stellar line-up of supporting musicians including Kim Paterson and Murray McNabb, and received reviews to match.

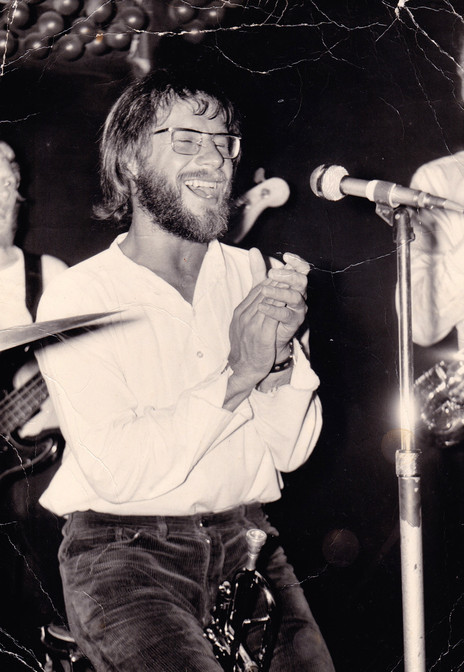

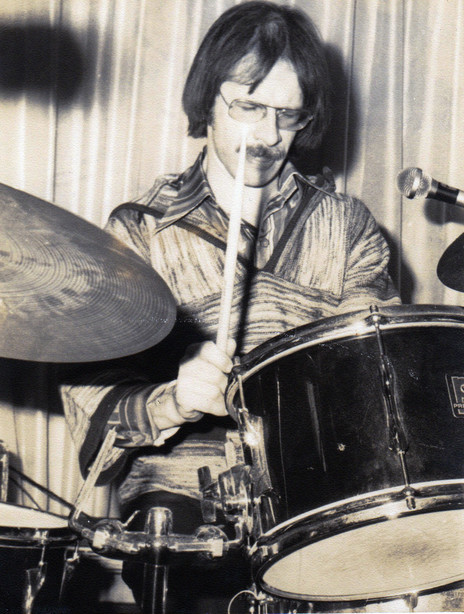

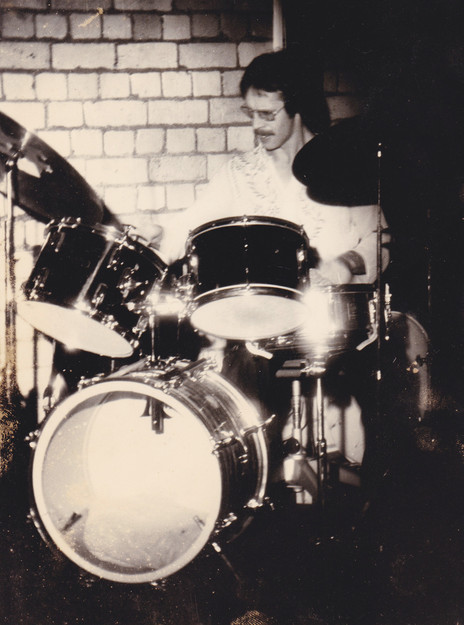

Kim Paterson on drums, 1971: "I was in Manila, Philippines playing trumpet in an 11-piece soul band entertaining American troops on R&R from Vietnam. This was me jamming on drums with a soul band after hours. I'd been drinking and the drums gradually disintegrated."

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson (flugelhorn, percussion), Kevin Field (Rhodes), Lewis McCallum (tenor & soprano saxophone), Cameron McArthur (bass), Stephen Thomas (drums) @ Backbeat Bar for the CJC Creative Jazz Club, Auckland, April 04, 2018.

Kim Paterson's The Duende, released May 2012 on Sarang Bang.

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

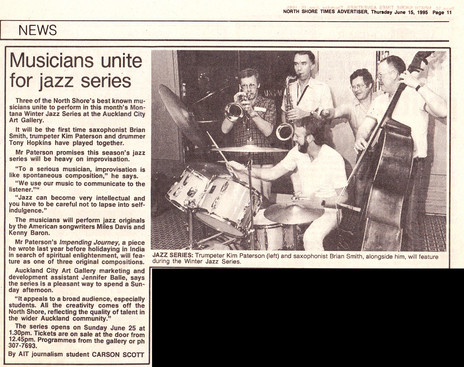

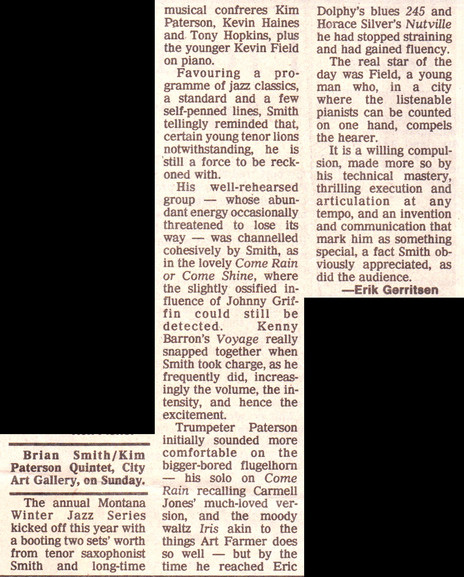

Kim Paterson with Brian Smith at left.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Jimmie Sloggett performing at Western Springs in Superpop 70. Kim Paterson can be seen in the far distance over his shoulder.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

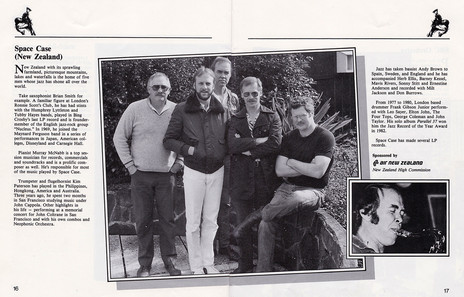

New Zealand jazz funk fusion band Space Case, active in the early 1980s. Clockwise from top left: Kim Paterson, Brian Smith, Murray McNabb, Andy Brown, Frank Gibson Jr.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Space Case, from left: Andy Brown, Frank Gibson Jr, Brian Smith, Kim Paterson, Murray McNabb.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson at home in Hong Kong while on contract to the Hong Kong Hilton, around 1972-73.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

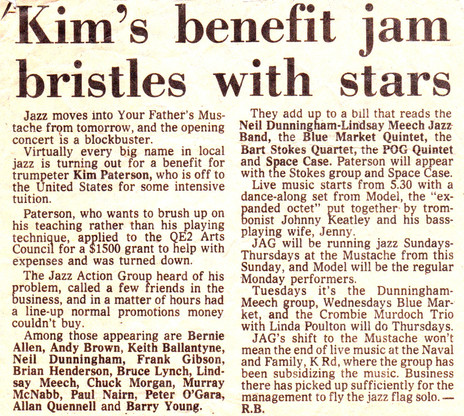

The jazz community rallies around to help Kim Paterson get tuition in the USA.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson on drums at Your Father's Mustache, Auckland, with Andy Brown (bass), Bart Stokes (saxophone), Chuck Morgan (guitar).

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson, second from left after playing drums for American trumpeter Bobby Shew at Mainstreet Cabaret. Bassist Andy Brown is at left and Murray McNabb (not pictured) was on piano. Also pictured, Ray Edmondson (second from right). Edmondson had jammed with Clifford Brown in the US and was present at the famous 1953 Massey Hall concert of Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Edmondson was later known as the masked jazz-hip hop performer "Killer Ray" and performed at Auckland's Big Day Out and Squid bar.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

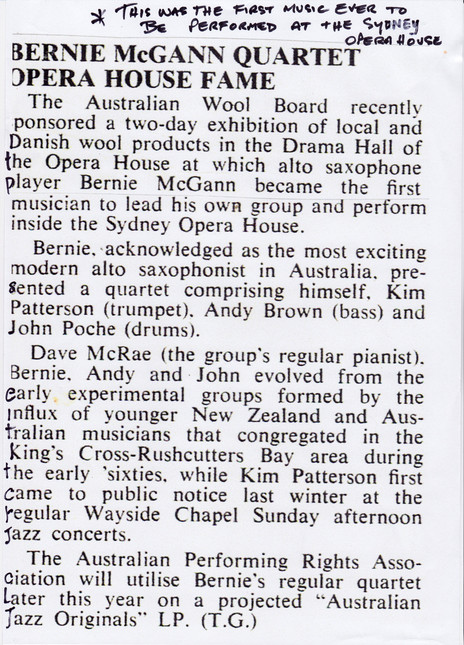

As part of the Bernie McGann Quartet, Kim Paterson was among the first players to perform at Sydney opera House.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

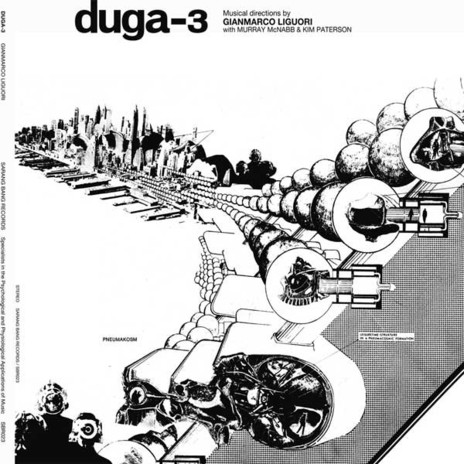

Gianmarco Liguori with Kim Paterson and Murray McNabb - Ancient Flight Text (2009, Sarang Bang)

The Claude Papesch soul band, which included Papesch (piano, vocals), Kim Paterson (trumpet), Stu Parsons (baritone saxophone), Bernie McGann (alto saxophone), Tony Hopkins (drums), Andy Brown (bass), with Joy Yates on lead vocals. Kim Paterson: "We covered Ray Charles music plus some originals ... we also did a quintet with rhythm section and Bernie and I out front. We did Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Cannonball Adderley and some originals."

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson on trumpet, back row second from left. Paterson was on a six-month contract at Thredbo Alpine Hotel in NSW, Australia, playing drums in a jazz quartet and trumpet in an eight-piece soul band. "Also skiing six hours a day!"

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Bernie McGann and Kim Paterson, Wayside Chapel, Sydney, 1966.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson on valve trombone.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Duga 3: Gianmarco Liguori with Murray McNabb and Kim Paterson. Released in February 2012 on 12-inch vinyl.

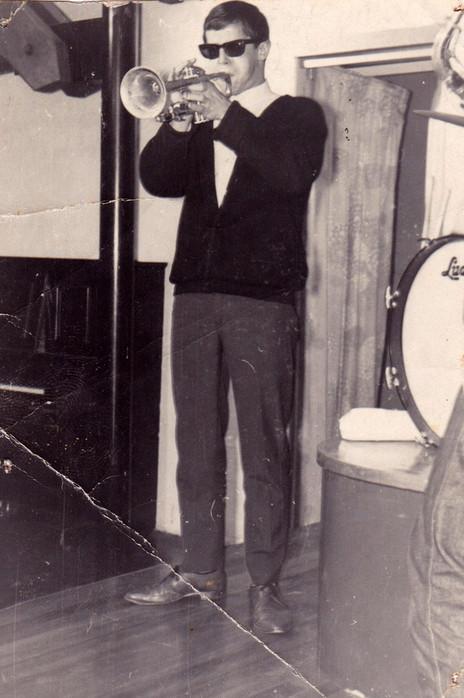

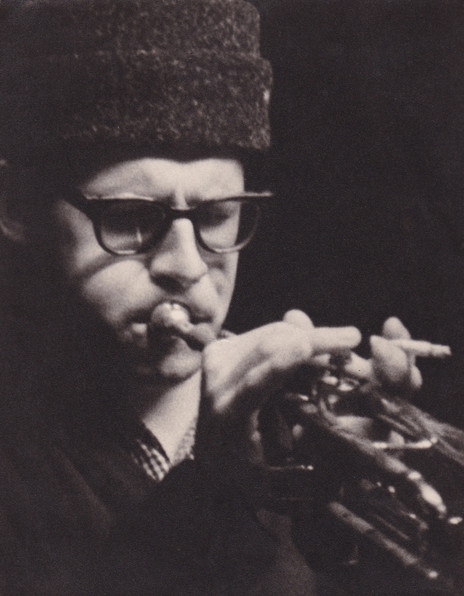

Kim Paterson, aged 18-19, photographed around 1958-59 at saxophonist Brian Smith's flat.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson with Denis Hepi and Walter Bianco between sets at a bar in St Heliers, Auckland, early 2000s.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson on drums in a disco band at Cleopatras, late 1980s. Beaver was the vocalist.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

A young Kim Paterson playing his first cornet in 1955: "Aged 14 with my James Dean haircut and my uncle's jacket."

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

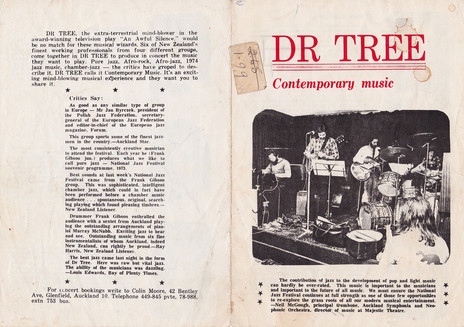

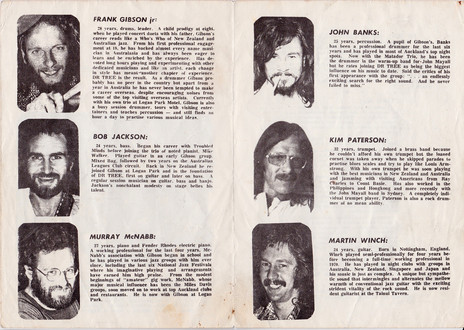

Dr Tree press kit. Members were Frank Gibson Jr on drums, Bob Jackson (bass), Murray McNabb (keyboards), John Banks (percussion), Kim Paterson (trumpet), Martin Winch (guitar).

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson on drums.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

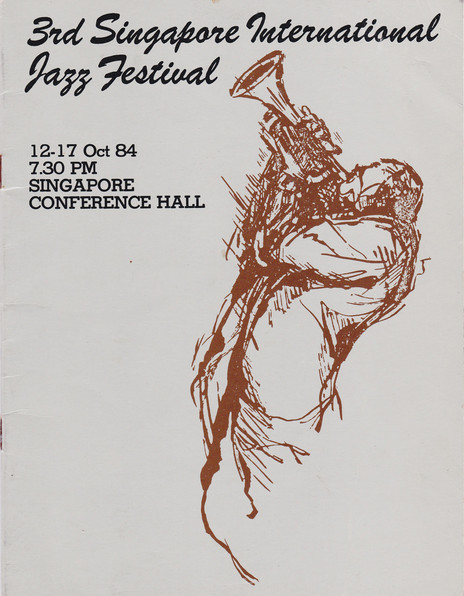

Third Singapore International Jazz Festival 1984 programme.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson (centre back) on trumpet, Thredbo Alpine Resort, NSW.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson and Mark de Clive-Lowe.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson on drums.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson onstage at Your Father's Mustache, Auckland, with Space Case: Frank Gibson Jr (drums), Bruce Lynch (bass), Murray McNabb (keyboards).

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

An image taken for the cover of Frank Gibson's Jazzmobile, a group that made one album for Kiwi in 1987. The lineup was Frank plus Phil Broadhurst (piano), Brian Smith (saxophone), David Woodbridge (trombone), David Colven (saxophone), Andy Brown (bass) and Kim Paterson (flugelhorn and trumpet).

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson at right with daughter Mareea Paterson on bass.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Alan Broadbent’s farewell concert at Embers Nightclub, Auckland, 1965. Kim Paterson on trumpet, Tony Baker (alto saxophone), Bernie Allen (tenor saxophone), Frank Gibson (drums), Alan Broadbent (piano), Denny Boreham (bass). All music composed by Alan Broadbent.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson and Kevin Haines at the London Bar, Auckland.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson on trumpet, Wayside Chapel, Sydney, 1966. A weekly gig with the Bernie McGann quartet, which included Andy Brown on bass and John Pochee on drums. The music was a selection of Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker and Ornette Coleman tunes, and McGann originals.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson Quintet - 57th National Jazz Festival, Tauranga 2019.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Dr Tree members profiled: Frank Gibson Jr, Bob Jackson, Murray McNabb, John Banks, Kim Paterson, Martin Winch.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Kim Paterson on flugel horn.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection

Corporate gig during the 1990s with Bernie Allen on alto saxophone, Kim Paterson on trumpet, an unidentified saxophonist, Barry Young on drums, Alan Quennell on guitar. Pianist is thought to be Phil Broadhurst.

Photo credit:

Kim Paterson collection