She obtained a Bachelor of Arts from Auckland University of Technology (AUT) in 1997; studied classical piano, guitar theory and cultural and intellectual property, and was awarded “best Māori album” in 2001.

In 2004 Whirimako received the APRA Maioha Award for her songwriting in te reo and the Te Waka Toi Award for her contributions to contemporary Māori music.

Whirimako was made a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to Māori music in the 2006 New Year Honours and received a best performance nomination in the Asia Pacific Screen Awards for her acting debut in the 2013 film White Lies.

She has twice featured solo with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra (NZSO), performed three shows at a leading world music festival The Dreaming, and represented her country at the Anzac commemorations at Gallipoli.

She toured Asia with guitarist Lance Sua for Trade New Zealand and the Ministry of Culture & Heritage, appeared at Womad and various jazz festivals and in 2008 was featured singer with the NZSO and Salmonella Dub in the Feel The Seasons Change show, combining modern music, ancient instruments and te reo.

Whanau of songbirds

Whirimako Black was surrounded by music growing up in the foothills of the Urewera ranges, deep in Tūhoe country where her mother, cousins and sisters were all singer-songwriters.

“The look on their faces when the whānau sang was that they were having the best time ever and I thought as a young girl, I want some of that.”

She loved to see them expressing themselves “with a smile, hands moving and looking at each other when they sang. Then they would break out and do a kapa haka song which Mum and her cousins composed.”

It was far more than just entertainment but an important expression of culture. “They’d bring their songs to each other and say, ‘have a listen to this’ or travel to Turangi for example to get a song to bring it back to a kapa haka group Mum was involved with.”

This, says Whirimako, is part of the glue of the Tūhoe culture, to pass things down, to retain and maintain.

Finding her own way in the music industry and taking some of the songs she heard on the marae and at family gatherings was not always easy or understood, particularly when she improvised or added her own elements and styling to songs that were sometimes over a hundred years old.

“I’ve done that since the early 90s. Some love it and some are sceptical because that’s not how it’s done traditionally.”

She says her phrasing and influences for English songs probably come from listening to the early black singers of her mother’s era: Nat King Cole, Diana Ross, Dionne Warwick, Vicky Carr and “Mahalia Jackson in the days of black-and-white TV when she had her own show.”

A deep heritage

Initially Whirimako was unaware of anyone performing in te reo within the music industry other than her cousin: composer, singer and traditional Māori instrumentalist Hirini (Sydney) Melbourne.

She was also inspired by fellow Tūhoe songstress Kui Wano, who along with Hirini, “made te reo authentic” giving her something to aspire to.

She later discovered that her uncle, Te Arawa elder Hori (George) Tait, wrote the Māori words for Deane Waretini’s ‘The Bridge’, the first chart-topping song to be sung in te reo, and worked with him on the title music for Māori news programme Te Koha, hosted by the late John Rangihau.

In further exploring her whakapapa she was delighted to discover music ran in the family generations back.

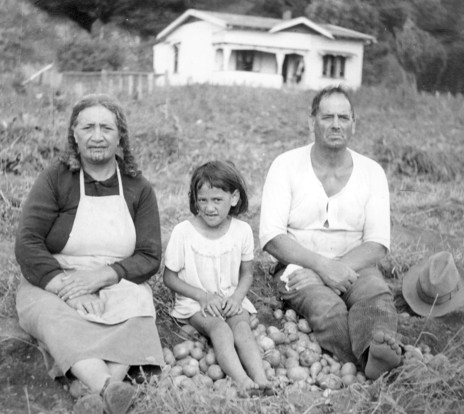

She followed the lineage from Tuhoe Potiki, grandson of Toroa the captain of the Mataatua waaka, “down to my great grandmother Nanny Pihitahi Trainor who recorded some songs … and was picked by Sir Āpirana Ngata to be his kaikaranga when he came through the Tūhoe area.”

Nanny Pihitahi also submitted waiata on behalf of Tūhoe for Ngata’s Ngā Mōteatea (traditional songs) of Ngāti Porou.

Early on the air

Whirimako’s performing debut was as an 11-year-old singing a composition written by her sister, an adaptation of ‘Up On The Roof’, for the opening of Māori news and current affairs on Radio Whakatane 1XX.

When she was about 15 years old she was in a Bay of Plenty covers band that won a talent quest and a residency at the Te Rapa Tavern. Her next unit was Black Label and then she joined Kawana, a group of musicians who had played with Howard Morrison and Prince Tui Teka.

On turning 18, her older brother bought her a one-way ticket to Australia. The hope was that a relative with contacts in the music industry and ocean cruise bookings, would give her a kick start.

Whirimako imagined life playing aboard ship but spent most of her time in a “home studio like a little dungeon” singing songs written by her relative and a friend, trying to impress US publishing companies.

There were no contracts or cruises, so she enrolled at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music to study music theory, improve her skills at the piano and learn to read and write music in 1983. From 1985 when the money ran out she teamed up with a flamenco guitarist playing café music.

By this stage Whirimako had two children and was co-managing a pizzeria-video shop with her partner. Things weren’t working out after nine years, so she and her children returned to Aotearoa to start afresh.

Ancient welcome home

On her return, her elder sister sang her the ancient song ‘Taku Rakau’, written in the 1830s by famed Tūhoe and Mātaatua ancestor and composer Mihi-ki-te-kapua from Ruatahuna. “I cried and cried when she sang that to me, it was my welcome home. That was part of the journey of coming back to who I am.”

Whirimako was determined to perform original and traditional songs in her own style, sustained by a powerful spiritual impression. “I had a dream or a vision … if you are going to put yourself out there, do you want to be singing English songs or be who you are as Māori?”

She began to take up the challenge. “There was much talk about Māori race losing its language and who they are because of colonisation. I’m from the last tribe in Aotearoa to be colonised so we have a lot of waiata, tikanga and protocol that is still in place.”

After being commissioned to write the theme music for one of Claudette Hauiti’s TV sports shows it was suggested she get a band together.

After talking to Karen Brown at the Taneatua Hotel in 1991, an all-female unit Tuahine Whakairo (Sisters In Art) was born.

“We practised at Ruatoki with Karen’s partner [at the time] Tame Iti as our chef, chauffer and roadie supporting us a hundred percent. We struggled though, because we were all poor and solo mums.”

The seven-strong band of women with varying musical capabilities and “six lead vocalists” played a variety of gigs including Java Jive in Ponsonby, and the 1993 Women’s Refuge event at The Gluepot MC’d by Karyn Hay.

“When we let our vocals go we bought the house down, particularly doing David Grace’s song ‘Rua Kenana’.”

Keeping the band together was “too hard” for a variety of reasons but “that’s where I got the buzz of writing songs including in te reo,” says Whirimako.

Out of the mist

Her first album was going to be Hohou Te Rongo: Cultivate Peace but after writing and preparing a number of songs she put that project on hold.

Whirimako’s growing sense of connection to her musical heritage, and her favourite book Tuhoe: Children of the Mist by Elsdon Best, were the inspiration for what came next, along with the knowledge that one of Best’s main sources was Tamarau Waiari, a direct ancestor of her mother. “I thought, I’m reading about myself, it’s got to be OK.”

The album Hinepukohurangi: Shrouded in the Mist took shape over four years from 1996. She became deeply anxious, even taking up smoking to hide her inner shyness and concerns about how whanau and iwi might react to her version of songs from the marae.

Deep inside, however, she knew this was what she wanted to do; soon after the album’s release, she felt great relief and kicked the smoking habit.

Shrouded In The Mist won Best Māori Album at the 2001 NZ Music Awards; it featured the track ‘Taku Rakau’, which had welcomed her home from Australia.

“My younger cousins and others in my age group who were living away from home or overseas cried when they heard that first album because it brought them back to themselves. My gut feeling was I knew that would happen.”

The album resulted in an invitation to compose and sing on the titles of the Landmark Productions documentary of James Belich’s The New Zealand Wars.

Return to peace

She quickly returned to the project she had been working on behind the scenes, Hohou Te Rongo, inspired by her daughter, Mihi Ki Te Kapua.

“My whānau [family] are my puna, my source. Each whānau member has a quality and values that fit in with me. In each area, they come through and tautoko [support] me. We all love music and I value all their opinions.” The self-produced album was released in 2003.

Mai Music had been wanting to back her career but she held off until she got into a sticky situation over a recording project which, after a false start, she agreed to strip back and start again.

She signed with Victor Stent of Mai Music to create Tangihaku, an intimate recording session with Joel Haines on acoustic guitar and Whirimako’s long-time collaborator, Justin Kereama, on taonga pūoro (traditional instruments).

It was based on a collection of poems written by her mother Anituatua Black, and older sister Rangitunoa Black, set to music composed by Whirimako and her sister, and arranged by Haines. It was released in May 2004.

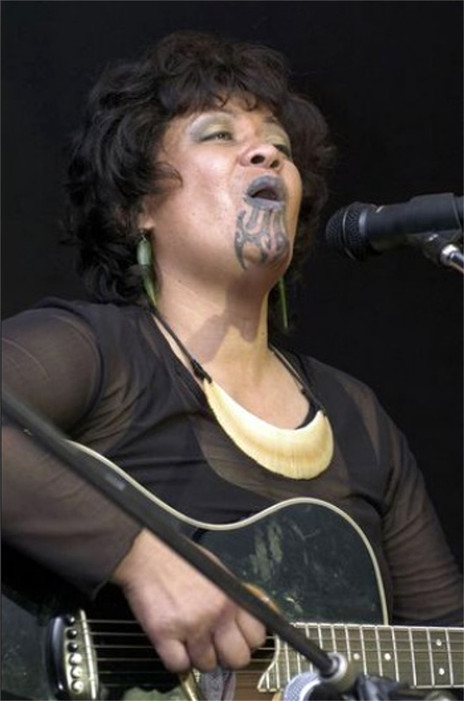

Meanwhile, Shrouded In The Mist resulted in her first international invitation. She was walking past Inia Taylor’s Moko Ink in Grey Lynn,when her son pleaded to have a tattoo. She relented and admitted to the artist she had no money but could offer a copy of her newly released CD.

He completed what she thought was a Māori tattoo: “I discovered later it was Hawaiian.”

Taylor, well connected in the music industry, played it to English musician Jamie Catto, who along with Duncan Bridgeman formed electronic world music band 1 Giant Leap.

World music ambience

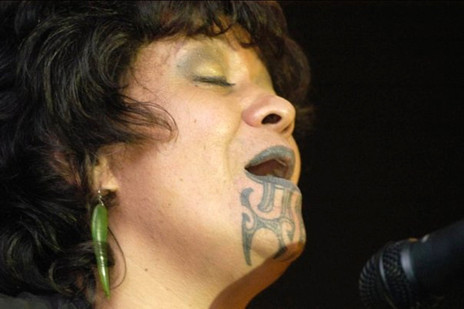

The cross-cultural collaborative unit was looking for an indigenous Māori singer for their first album. “My uncle, Hirini Melbourne, wasn’t available but Jamie heard my album while he was getting a six-hour tā moko.”

He called the next day saying “it had transported him to another place; that it was soothing and took his focus off the tā moko he was getting.”

Whirimako was then invited to the home of acclaimed Māori artist George Nuku, where they recorded two songs. “There was drum beat and one note on the synthesiser and I just did my recording over those bare bones.”

The songs she collaborated on were ‘Tā Moko’ and ‘The Way You Dream’ which both ended up on 1 Giant Leap’s debut album in April 2002 and the movie length DVD, with footage of her from the original recording session.

‘The Way You Dream’ was included on some versions of the soundtrack for the Jackie Chan movie Bulletproof Monk and licensed for several compilation albums.

The connection with 1 Giant Leap resulted in an invitation to join the innovative world music duo at the Athens Song Festival in June 2004 in the lead up to the Athens Olympics.

Baba Maal, the other vocalist booked for their headlining gig, was held up by customs with passport issues so Whirimako became the only vocalist, performing to over 10,000 people — “the biggest crowd I ever sang to.”

Immediately after the Athens concert, 1 Giant Leap asked her to join them at the Glastonbury Music Festival, but she declined. “They were just too crazy for me … I was still very conservative but they were right out there with all these ideas … I just felt like they were going to bastardise my culture so I turned them down.”

She says they didn’t seem to know the difference between what was tapu (sacred or set aside) and what was noa (neutral) when it came to dealing with an indigenous culture.

On reflection, Whirimako says that was one of her great regrets. “A few years later when I saw Beyonce was singing there I realised I’d turned down an appearance before 150,000 people. Who knows what might have happened.”

Hooked on recording

Whirimako used the Athens opportunity to get the word out about her new album Tangihaku, including UK media interviews and a live performance on BBC radio in early September 2004.

Mai Music general manager Victor Stent said: “In less than 48 hours, Whirimako travelled from local artist to world music star,” with singers and musicians of every nationality, complimenting her on her new album, “proving the power of great original music to cross all barriers and languages.”

Stent said this was “a triumph for te reo, tikanga Māori [and] Whirimako's extraordinary ability to communicate her values and the beauty of her language in both the way she acquitted herself and in her moving vocal performance,” which, he said, left an indelible impression on the people of Athens.

After Tangihaku, Whirimako admits she was in love with the recording process and determined to go for 10 albums, something she had achieved by 2017.

She collaborated with oboe player Russell Walder for the evocative soundscape that comprised her fourth album Kura Huna (Hidden Treasures) a collection of ancient waiata and chants from the Mātaatua region.

“Tūhoe love the slow beats. They love the back beat, way back there,” Whirimako told the NZ Herald's Scott Kara (13 September 2006). “They don't like showing off like the tīrairaka [fantail]. You know, the bird that does all that fancy carry on. They don't like that. They like to be solid and firm.”

Kara describes Whirimako's music as “gently paced, yet spirited and vital” acknowledging her as one of the most prominent Māori voices on the local scene.

Bilingual soul

Her fifth album, Soul Sessions, in 2006, featured her take on 11 popular jazz and blues standards translated into Māori, including ‘Stormy Weather’, ‘Black Coffee’, and ‘Summertime’, and another four in English.

“My agenda is that Pākehā will catch on to this language of ours and start using it. So ... anyone who's non-Māori will enjoy the music and think, ‘Oh, that’s a lovely, soft sounding language.’”

Learning about traditional Māori songs and music, involved tracing the whakapapa of a song, and also helped her understand the standards she performed on Soul Sessions.

"I've always been a great believer [that] when you sing a song you've got to own it. That's the only way to give it the mana it deserves,” she told Kara. “If a singer can lift someone to a higher plane then that's a magical performance. Music certainly reveals my soul."

The bilingual jazz album featured father-and-son team Kevin Haines on bass and Joel Haines on guitar, along with seasoned players Kevin Field on keyboards, Ron Samson drums, Kim Paterson on flugelhorn and Alan Brown on Hammond organ.

Soul Sessions was the fastest-selling New Zealand jazz album of 2006, entering the finals in the Best Jazz Album category of the 2007 New Zealand Music Awards.

In his review, jazz aficionado Graham Reid lamented the lack of mainstream coverage of Whirimako’s previous albums. “Black's voice is a thing of great sensitivity, and those albums should have made her a household name.”

Reid wrote on his Elsewhere site: “Once again Black sympathetically takes listeners to the heart of a song, brings that soft but strong and supple voice into focus on the familiar melodies and, in the company of fine Auckland jazz musicians, brings a fresh perspective to songs which sound written by and for her.”

Affirming her sound

In 2007 she was back with Whirimako Black Sings, another compilation of classic jazz songs in te reo and English.

Her proudest moment, when her lifelong anxiety seemed to disappear, was performing as a guest vocalists with the NZSO at the 10-year anniversary of Te Papa's opening, in 2008.

“My mum and Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan were sitting side by side behind the string section; there were hundreds of people, and I sang perfectly with the orchestra … they were right there all the way and for some reason I felt totally grounded and relaxed and was able to express myself beautifully it was just divine.”

Whirimako received an Arts Foundation Laureate Award in 2011 as an artist of prominence, excellence across a range of art forms, and outstanding potential for future growth.

That year she stamped her unique vocal styling on a songbook of even more accessible 20th century classics, almost in defiance at the mainstream industry’s apparent indifference to her now significant cultural contribution.

The Late Night Plays, another self-produced album, had full English renditions of songs from U2, Joni Mitchell, Stevie Wonder, Billie Holliday, Etta James, Leonard Cohen, Sting and Al Green; each featuring her own style and phrasing.

Russel Walder, known for his own compositions on the Windham Hill Records label, joined Whirimako again, assembling top players for the album, including Michael Chaves on guitar, Aron Ottignon on piano, Kim Paterson on trumpet and Jonathan Zwartz on bass.

The Late Night Plays was recorded at Auckland's Roundhead Studios, with no overdubs on the live sessions.

Restating her commitment to the Māori language and the jazz idiom, in 2012 Whirimako delivered Te Reo Māori Sessions, a two-CD set featuring 20 classic jazz and blues standards.

This was followed closely by a collaboration with Richard Nunns on Rattle Records, Te More, using traditional Māori instruments in a tribute to 1870s composer Mahi-ki-te-kapua, a further acknowledgement to the ancestral songs that welcomed her back to New Zealand.

And for Whirimako Black the journey is only getting more interesting as she works up a new project of traditional Mātaatua songs and explores another expression of her spirituality, an album of gospel-focused songs due sometime in 2018.