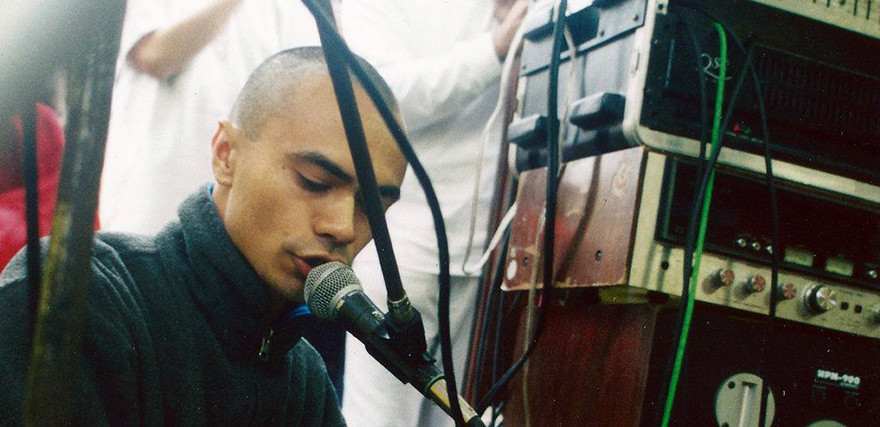

Denver McCarthy/ Micronism.

In March 2023, Micronism’s Inside a Quiet Mind (Kog Transmissions, 1998) received Independent Music NZ’s Classic Record award, part of the Taite Music Prize 2023. Created by Denver McCarthy, Inside a Quiet Mind was included in Grant Smithies’ 2007 book Soundtrack: 118 New Zealand Albums (CPP, 2007). His essay about the album is republished here with his permission.

--

Inside a Quiet Mind was the third release from Auckland label Kog Transmissions, a tiny independent label whose entire annual promo budget wouldn’t buy the Sony boardroom a round of lattes. Consequently, many people never got to hear it, and that’s a great pity, because it remains the best electronic album ever made in this country. Luxuriously melodic, rhythmically complex, tinged blue with sadness, and – occasionally – bright red with joy, it is a record that’s not so much touched by the hand of God as given a lengthy massage.

The album was recorded on a fairly basic bedroom studio set-up when Tokoroa-born producer Denver McCarthy was just 21. It wasn’t McCarthy’s first record – he’d previously recorded a brace of scalding hardcore techno tracks for American producer Lenny Dee’s Industrial Strength label, some of them under the related moniker, Mechanism – but it remains his most introspective and his best.

People have called it an “ambient” record, but I disagree. Certainly, it’s not ambient music in the insipid and soporific New Age sense. Echoing flutes, fuzzy guitar arpeggios, Vangelis-on-Valium synth washes, tabla and whale song are all thankfully absent. Admittedly, many tracks here share qualities with the more cerebral ambient music of composers such as Brian Eno or Erik Satie in that they calm the mind while also leaving it feeling more alert and focused, but, overall, what we have here is techno, pure and simple – or in this case, pure and complex.

Micronism - Inside a Quiet Mind (Kog Transmissions, 1998)

Though entirely instrumental, these are songs rather than facile DJ mixing tools or superficially funky club fodder. Each song has a discernable beginning, middle and end, and a thematic through-line. Musical ideas are introduced, developed, explored from different angles, and then resolved before the final fade.

It’s clear that McCarthy has studied the electronic music of Detroit very closely. His albums share a pervasive soulful melancholia with those of Detroit techno pioneers Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson, Derrick May and Carl Craig, and also the meticulous drum programming and thick robo-funk basslines of Detroit electro outfits such as Dopplereffekt, Drexciya, Ectomorph, and Flexitone.

I talked to Detroit producer Carl Craig when he performed in Wellington in 2005. He explained to me why he thought Detroit techno sounded the way it did. “Detroit is one of the most desolate, crime-ridden places in America,” he said quietly. “You drive around the city and there’s all these monolithic factories with blown-out windows. There’s burnt-out cars like a war zone, and crack-heads wandering around the wreckage. It’s very worn-out looking, but also very futuristic looking, like something out of Blade Runner or Robo-Cop. When we were inventing this music as teenagers, we all thought automation, computerisation and electronics were the things that were going to transform society and lead to a better world, which is ironic, because they’re the things that actually put all the factory workers in Detroit out of work and made this place so damn bleak. But my point is, we made this kind of music because we wanted to imagine alternative realities. And we made our music to make the place we were living in more beautiful.”

Detroit techno wasn’t about escapism, as people so often suggested, Craig said. It was all about beautification. It was about creating a unique kind of urban renewal programme you could dance to.

“Techno is driven by an obsession with the future and what the future should be, and it’s an attempt to represent that in sound. The best techno music sounds like nothing you’ve ever heard before, yet the mood it’s expressing is instantly familiar. When you get a bunch of black ghetto kids reporting on what they see around them, that’s hip hop. But when a bunch of black ghetto kids with electronic instruments start dreaming of alternative futures, that’s techno.”

And when you get a young Māori kid with a vivid imagination, a burgeoning spirituality, a bedroom full of electronic instruments and an intensely beautiful natural environment to respond to, you get Inside a Quiet Mind. It’s as if McCarthy has sat himself down in a shady clearing in the New Zealand bush, plugged his instruments into a portable generator, and got to work, distilling what surrounds him – deep green leaves, bellbird calls, smooth round stones, icy water, scuttling insects, clammy mud – into a forest of fluttering frequencies. He has taken a musical style born of cracked grey concrete and urban desolation and employed it to express a thousand shades of green. It seems entirely apt that the Inside a Quiet Mind disc itself is screen-printed with a photo taken from the forest floor, looking up to the sky through the fronds of a gigantic native tree fern.

So, press Play and what do we hear? The album fades in on a distant bass throb and crisp Carl Craig-inspired high hats, and carries on for another seven and a half blissful minutes with just subtle changes in high frequency cymbal percussion and low frequency bass churn. It’s a track that has always said a lot to me about McCarthy’s aloof relationship with the local techno scene. It sounds as though the listener is on top of a high hill and somewhere down in the valley, a couple of miles away, a huge outdoor dance party is happening. Distance has dulled all the bright middle frequencies, and music that would be intense and overwhelming up close has become wistful and hypnotic.

Ironically, the next track, ‘First Reflections’, really was played at outdoor dance parties all over the country for many years. With its extended intro of echo-heavy keyboard runs, bountiful sub-bass and a profusion of chords that melt away like sugar on your tongue, it became Aotearoa’s first indigenous techno anthem, and to play it today is to be teleported back into a corner of the House Tent at The Gathering at 4am, smiling until your face hurts, the room liquid with spinning mirror balls.

But the track that always sends the needle on my genius detector way up into the red zone is ‘Rainbow City’, three minutes of thrilling electro-squelch laid over a beat like a square wheel travelling down a bumpy road. The analogue synth riffs here seem to be under pressure, starting off somewhere deep in the earth and then having to bubble up through several layers of denser, more viscous keyboard sounds. Imagine a conversation between two robots. One of them has been on holiday, visiting the “scenic wonderland” of Rotorua for the first time. It comes home, and tries to describe those boiling mud pools to its mate. These are the noises it makes.

A similarly high standard prevails throughout the rest of this album. McCarthy keeps rolling out gem after gem – the buoyant euphoria of ‘Twinkle Twinkle Little Star’, the cavernous dub of ‘Restless Address’, the strangely tender dance-floor cut ‘Engaging Causeless Mercy’, the sleepy haze of ‘An Unfulfilled Wish’, which subverts a fairly traditional hip hop break-beat with updrafts of keyboards that hover, shimmering, like musical mirages in the heat.

As a man who long ago chose meditation over drugs, McCarthy is probably not chuffed with the fact that this generously emotional album became our nation’s premier post-E comedown record for several years. Or perhaps he couldn’t care less. McCarthy has written of himself as a person “chosen” to make music, which seems more a reflection of his religious belief in predestination than any glimmer of arrogance. He has also written that he sees Inside a Quiet Mind as an aid to silencing the mental commotion that is central to modern life.

“The mind can be quite chaotic at times thoughts arising and falling of our own illusions (dreams, aspirations) and realities (day-to-day living). Surely all this movement brings fatigue? Reading chaos is no easy task, taming the chaos seemingly impossible. Creative construction can be a great focus for one’s mind, for both the givers and the receivers. It is this focus which has the ability to capture a mind and elevate its thoughts to those aside from illusion and reality, and sometimes to the graceful platform of the quiet mind.”

So, this is an album designed to help you get to that mystical third place, to achieve a peaceful blankness where your mind is unencumbered by either reality or illusion. Never found such a place myself – my head’s always busy as a bottleful of bees – and last I heard McCarthy was still trying, living in a Hari Krishna compound near Wellington, chanting and meditating, and occasionally still making music. What he might come up with in the future is anyone’s guess, but I expect great things.

The man has a rare gift for coaxing warm spirits from cold circuitry, which is why Inside a Quiet Mind gets inside you, soothing your soul and reaching deeper emotional places than any other local electronic music to date.

--

When advised of the 2023 award McCarthy responded, “This acknowledgment of my small contribution to New Zealand music is wildly misplaced – so it is received with great shock and even greater humility and gratitude. Looking forward to trying to fire up the machines once again, to journey into the land of Electronica, forgive me if I take a few wrong turns ... it has been a while ...”

In 2018, 20 years after Inside a Quiet Mind was first released on CD, Kog re-issued it on vinyl and digital platforms; another vinyl pressing is planned.

Like the Taite Music Prize main award, the Independent Music NZ Classic Record is a critically judged award for originality considering the artistic merit, creativity, innovation and excellence of an album in its entirety irrespective of album sales, artist popularity, previous awards or international achievements.

--