The Proud compilation of 1994 was a game changer. This was South Auckland in a new light – contemporary, confident and unapologetically Polynesian. If it appeared that each act had emerged from nowhere fully formed, that was simply because few had been paying attention. They also shared a connection beyond regional geography, a place everyone had visited and benefitted from in one way or another, the Otara Music Arts Centre, otherwise known as Omac.

Omac auditorium exterior and mural, 2020. - Steven Shaw

The building itself was a community facility going back to the Polynesian immigrants who settled in the area during the 1950s. Sitting alongside the Otara Shopping Centre, it was where socials were held, churches met, bands played, meetings were conducted, boxers trained, and kids hung out.

The concept of transforming it into a dedicated arts centre was first mooted in 1976, so when the Manukau City Council began questioning its future in 1980 it became time for a serious community intervention. First pushed in 1981 by Whakahou, a multi-cultural collective of long-term residents, and then taken up by the students from the local secondary schools, the council put up $3000 to investigate the concept.

This was also when Noma Sio-Faiumu began rehearsing there with Hillary College’s school band, Karma.

“[The centre] gave us access we’d never had. We could touch a speaker or pick up a microphone and I’d never had that. Our school had limited resources, not even a record player, so it took me ages to learn the song we were working on because I had no way of listening to it. Then when I finally heard it [at Omac] I realised I was singing all the wrong words.”

Omac reception entrance.

The facility also gave Karma access to a 4-track recorder, but still without a studio it was set up in an office alongside the Citizen’s Advice Bureau inside the mall.

In 1984 the council approved a $1.7 million upgrade, with the refurbished building being opened by Govenor-General Sir Paul Reeves in July 1988.

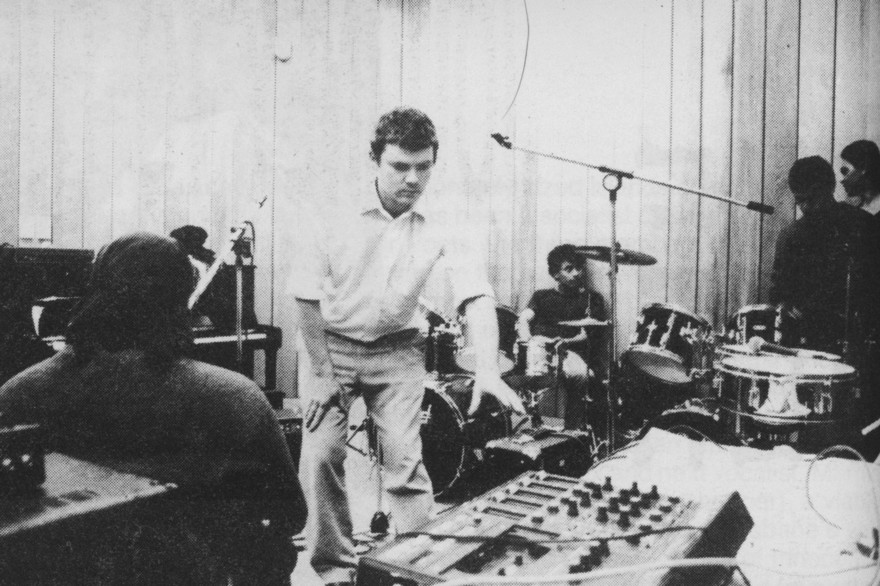

But if Omac offered artists the chance to hone their talents and produce original material, that’s where it ended. Until Tim Mahon came on board.

Tim Mahon in the studio at OMAC, 1988. - Paul Casserley, Book of Bifim 1988.

The former bass player with North Shore post-punks Blam Blam Blam had left for London after recuperating from a road accident: “I was very ill. I’d been in a coma for a couple of weeks, in crutches for 18 months, and I didn’t want the poor me thing, so I split to London at the beginning of 84. I just worked, did some gigs, and had a little band, the Dead Sea Scrolls.”

He returned in 1987 and not wanting to rejoin the central city music scene, began looking for new opportunities. The Blams had worked in South Auckland schools for the government’s PEP (Project Employment Programmes) scheme, so he knew Manukau City Council development manager Dale Hunter and secured an interview for Omac’s new position of programme manager.

Omac - main studio room, 2020. - Steven Shaw

Pitching himself as a conduit to the wider music industry, he soon found himself knee-deep in culture shock.

“I had no idea what I was getting into, I just thought it was a wonderful project to have a music centre in a place like Otara. So I started (networking) and … Otara, you have to realise it is a really strong community, it’s the capital of Polynesia – more politics goes down there in a day than happens in the Beehive – and the talent, that was the incredible thing. A guy would wander in the door to enrol: ‘OK, what class to you want to take?’ ‘Oh, I play a bit of drums, I can play the bass, and a bit of guitar, and the piano. Oh, and I sing.’ It was amazing.”

Noma Sio-Faiumu, now a fixture at Omac, had linked up with her school music teachers, Teina Benioni and Peter Hoera (who both played with Ardijah), to form Bamboo, and Mahon liked what he heard. As one of his first projects, he convinced a bigwig from PolyGram to drive south for a listen.

Omac reception area, 2020. - Steven Shaw

Not only did they go on to release to two 45s, Mahon hustled the support slot for the BB King/ U2 gig at Western Springs. “I rang the promoter and said ‘look, PolyGram just signed this new act and they really want them on the bill.’ Then I rang PolyGram, ‘I just heard from the promoter and they’re looking for a Polynesian act to go with BB King and U2.’ Then they talked to each other not knowing I’d spoken to them.”

After the gig, Noma got the signatures of King and all of U2 on the only paper she had, a $20 note, only for the band to use it to buy KFC on the way home.

Mahon spent three years in the role before becoming event manager for Manukau City Council, but in that time he set up a Performing Arts Award (now known as Stand Up Stand Out or “Suso”) while making the connections that would lead to the release of Proud and its follow-up national tour.

His dream had been to create a label, O-Town.

Omac - studio control room, 2020. - Steven Shaw

One group, Napoleon and the Lost Liku Lovers, recorded an album at Omac that went on to sell about 70,000 copies throughout the Pacific. This got the council very interested.

“I thought that (albums) should have kept happening, but then the council said, ‘hey there’s an income stream here, it’s a business’… it wasn’t a business.” Prices went up and progress stalled.

Still in his subsequent role as event manager, Mahon got Omac involved in the arts festival that ran parallel to the 1990 Commonwealth Games and later enlisted several acts born out of the centre – including Bamboo – to play at the Wildflowers Festival headlined by Annie Crummer and Dave Dobbyn in Hayman Park. Omac acts were also playing on the South Auckland “Big Kahuna” circuit that revolved around the Duke of Wellington, Cleopatra’s and Tamaki Tavern, and the venues run by the Black Power and Tribesman gangs.

A sign outside the Otara Music and Arts Centre (OMAC) receives a touch-up of paint, March 1992. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Footprints 03571

After reconnecting with producer Alan Jansson, Mahon also helped MC Slam and DJ Jam to record (at Jansson’s Uptown Studio free of charge) an anti-tagging single, ‘Prove Me Wrong’ (aka ‘Stop Tagging’) which got airplay.

This then became the favoured model because, he says, “Omac didn’t have the gear or the ability to navigate its way around council to produce a commercial project without having to pay through the nose which was silly because it still wasn’t a studio worth paying through the nose for.” This situation eventually improved with the purchase of a 16-track, 1" tape mixing desk, but pricing remained an ongoing issue.

Omac's now-vintage gear – a 16-track Tascam recorder and 2-track mastering recorder. - Steven Shaw

At the same time Mahon’s work in schools meant he had encountered new talent – the Semi MCs, Pacifican Descendants (the Sagala brothers), Sisters Underground, and the Vocal Five, while the Fuemana brothers (playing as OMC) were using Omac as a rehearsal space. Most of these people were already gigging with Voodoo Rhyme Syndicate, and/or being managed and recorded by DJ Andy Vann.

As luck would have it, Jansson knew Australian Andrew Penhallow, who wanted to release a compilation of South Auckland tracks as a companion piece to an Australian collection.

Needing money to record, Mahon got support letters from artists such as Neil Finn and Mike Chunn and convinced the council to back their application for a $30,000 grant from Labour government cabinet minister Parekura Horomia.

Proud: An Urban-Pacific Streetsoul Compilation (Second Nature/ Volition, 1994 / Huh! Records, 2000).

The resulting album, Proud: An Urban Pacific Streetsoul Compilation, was released in 1994 with three singles coming off it, Semi MC’s ‘Trust Me’ and Sisters Underground’s ‘In the Neighbourhood’ (which reached No.6 on the Singles Chart) and Otara Millionaires Club’s ‘We R The OMC’. The album launched the career of OMC and Pauly Fuemana in particular, who in 1996 had a worldwide hit with ‘How Bizarre’.

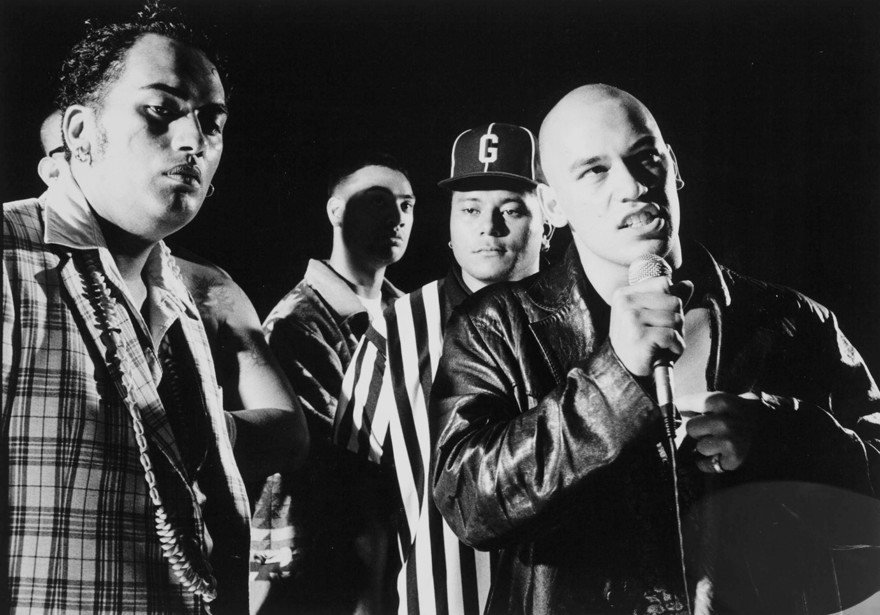

Proud Music Tour artists (L-R): Pauly Fuemana, unidentified, John "Loose Coolin" Nansen (with cap), and Paul Ave, March 1994. They were about to appear at a benefit concert at Hayman Park, Manukau, in memory of Mangere musician Eniasi Tokelau, 17, who had drowned in a swimming accident while the five week-long tour was in Murchison. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Footprints 03604

Despite Omac’s growing reputation, Mahon’s involvement wasn’t universally welcomed. At a planning meeting for the Proud tour he was accused of colonialism by activist/politician Willie Jackson and it took the support of Otara identity Phil Fuemana to settle things down.

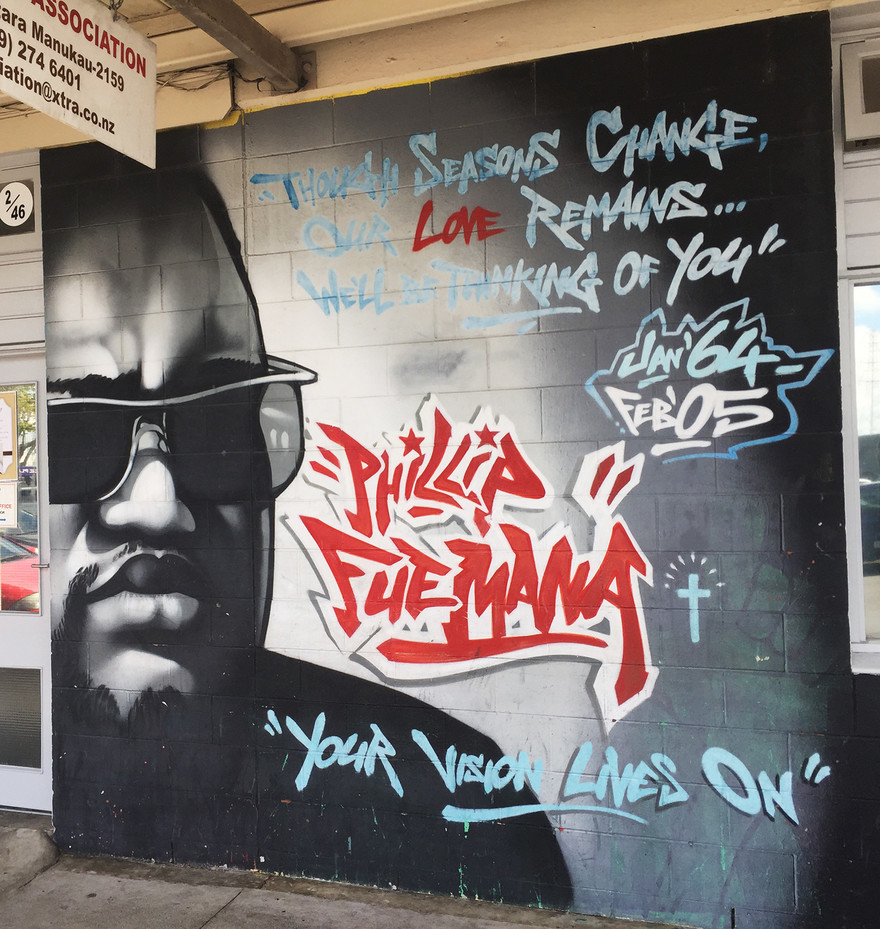

The early 2000s then saw a drop off in Omac’s community usage – mostly put down to digital home recording – which led the centre to introduce a “sound house” for teaching music software. The community then suffered two huge blows with the deaths of Fuemana brothers, Phil (February 2005) and Pauly (January 2010).

Phil Fuemana mural and dedication, Omac, 2020. - Steven Shaw

Omac remained popular with established acts for rehearsals and demos. A time sheet from this period shows acts such Ermehn, Dei Hamo, Matty J, Jamoa Jam, Lost Tribe, Che Fu and DLT using the centre over a single day.

After stepping up to serve as manager, Noma Sio-Faiumu left Omac to work with the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra. The APO’s education manager, Lee Martelli-Wood, had returned from a UK trip wanting to adopt a programme that mixed classical with hip-hop. Did anyone know of a venue?

From 2008, Omac (then ran by Greg Whaiapu) was home to “Remix the Orchestra” for 11 years, a run that was recognised by a Unesco award. One of the remixers was Noma’s husband, Matt Salapu, now better known as Anonymouz.

But Noma wasn’t done, and in 2012 she helped introduce a Venezuelan project, renamed Sistema Aotearoa, to Otara as well. This programme sees youth trained in classical music with the aim of building an orchestra good enough to compete nationally.

“These kids come from organic environments,” she says, “and now they can read and write music. That’s a huge advantage point, half of the musicians from those early Omac years still can’t read or write music, or write chord charts, and if we’d had that, who knows? So if this continues and the kids are supported they’ll not only be playing in classical sections, they’ll be creating new genres.”

Those prospects are currently under the care of OpShop (and formerly Stereo Bus) drummer and Omac manager, Bobby Kennedy.

“[Omac] is more than just a building, it’s a community, it’s the beating heart of the Otara Town Centre, and that’s something you understand when you walk in. They say walls have memory and I truly believe that here, you always feel something from different studios and performance areas, but with Omac, there’s something that just feels right even if I can’t quite put my finger on what that is.”

Omac, 2020. - Steven Shaw

In 2020 Omac’s studio is being renovated to include a new vocal isolation booth, new computers are being installed in the digital workshop rooms, and new programmes are due to be launched. In addition, Anonymouz was commissioned to produce a 30-part series of short interviews, which can be found on Omac’s Facebook page.

The annual Suso competition has expanded to include schools from outside South Auckland and is, as ever, producing new talent. Kennedy predicts big things for two current Omac students, singer-dancer-actress, Irene Folau, and vocalist Selika, this year’s Suso winner.

Omac’s success has also seen two sister facilities open, the Mangere Arts Centre (Mac) and Te Oro in Glen Innes. The budget remains tight. Kennedy manages four facilities with only one full-time employee, the receptionist.

Te Oro, Glen Innes, 2020. - Steven Shaw

But if times change, says Sio-Faiumu, the wider benefits of Omac’s work remain the same.

“Music can change lives. A lot of the people we grew up with could have ended up in jail, or ended up in not so good environments, but music gave them the opportunity to connect with themselves at a very deep level and express things that prevented them from ‘being’.

“I see kids I grew up with now, and I’m so proud of them because they’re the best dads, and maybe they wouldn’t have been if they hadn’t had that opportunity to discover themselves. Music is bringing change to our community.”

Omac auditorium and live performance area.

--