Mike Chunn is the New Zealand music industry’s best rebuttal to F Scott Fitzgerald’s maxim that there are no second acts in prominent lives. By the age of 40, Chunn had been deeply involved in local music, as a bass player with Split Enz and Citizen Band, an A&R man, a band manager and a record label manager; in the latter role he signed DD Smash and the Dance Exponents.

In the mid 1980s he looked for a purpose, with a late OE in Britain trying to find a foothold in the UK industry, before returning home with his wife Brigid, a family underway. A promised music role at the startup TV3 evaporated, and he concentrated on writing his 1993 Split Enz biography Stranger Than Fiction.

Then came the second act: his most significant achievements have occurred after he turned 40 in 1992. He became the general manager of music royalty collection society APRA – the Australasian Performing Right Association – increasing its profile, lifting its membership, and becoming involved in the campaign to boost radio airplay for New Zealand music. In 2003 he left to found and manage the Play It Strange Trust, which encourages secondary school pupils to write and record original songs. While at Play It Strange he helped get songwriting into the secondary schools’ curriculum. In early 2025 he stepped aside from his role at the trust, while remaining involved as an advisor.

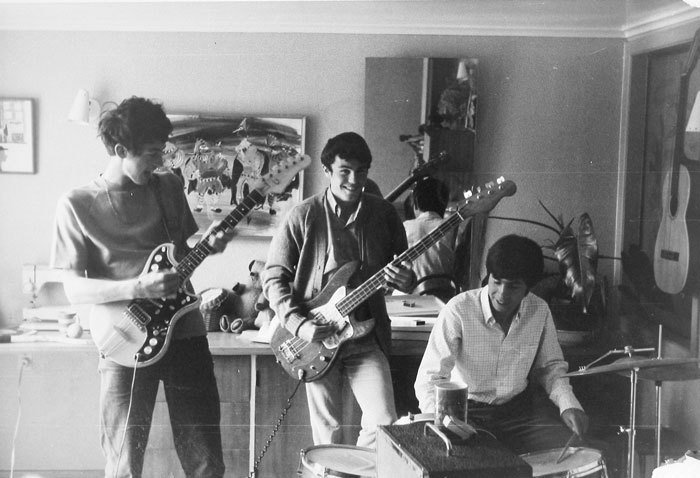

Pre-Ends: Geoff Chunn, Mike Chunn and Paul Fitzgerald, taken at the Chunn family home by their mother Yvonne Chunn

In the beginning was the Song. Although he only contributed a couple of songs and co-writes to Split Enz and Citizen Band, Chunn says he has been “obsessed” with songs from the age of 10. “I was always seeking out more songs to put in my life,” he told me late in 2024. His earliest memories are from a “banal” era of pop: ‘Tammy’ (Debbie Reynolds), ‘Fool No. 1’ (Brenda Lee), ‘Tower of Strength’ (Gene McDaniels), and the increasingly bland but ubiquitous Cliff Richard.

Luckily, his childhood piano teacher Mrs Beazley was open to teaching Chunn to play pop as well as Chopin. After an epiphany at the Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night, his awareness of the power of a song intensified. Fortuitously, his brother Geoffrey was adept at the guitar and songwriting. By the early 1970s both were present watching Phil Judd and Brian (Tim) Finn create and sing songs for Split Ends. “It was like finding a big seam of gold out on the footpath,” reflects Chunn. “A true sense of discovery.”

In 1975, after Split Enz had filled the Auckland Town Hall, his father Jerry quoted French-English writer Hilaire Belloc to him: “Write a good song and the tune leaps up to meet it out of nothingness … It is the best of all trades, to make songs, and the second best to sing them.”

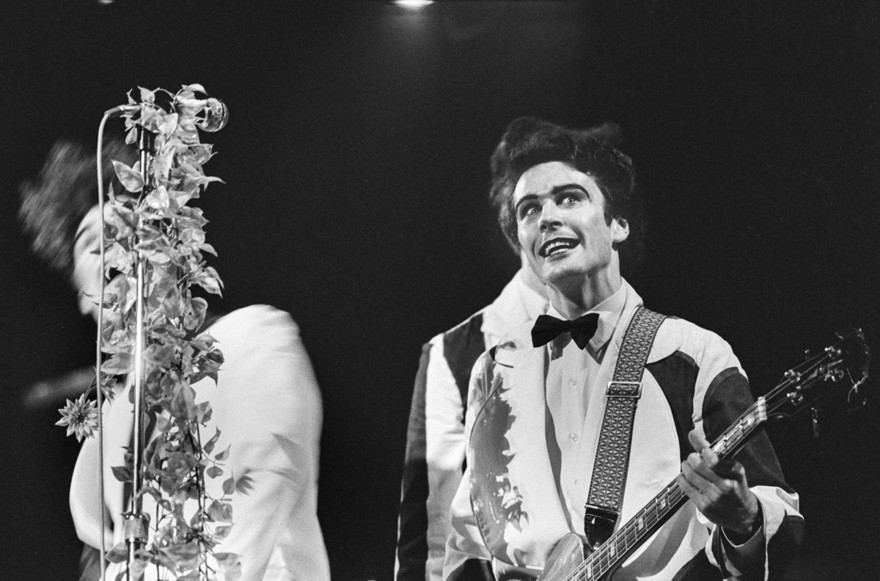

Mike Chunn, Split Enz, Auckland Town Hall, 1975; obscured are Tim Finn and Noel Crombie. - Bruce Jarvis, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1704-1043A-23A

Through the years Chunn’s raison d’être, his life’s purpose, became immersed in the importance of “the song”, and that sense of discovery has intensified. Hearing a new song emerge from a Play It Strange participant is an ongoing thrill that offers personal renewal. In late 2024, the current heart starter was ‘Eyes of a Child’ by Gisborne Girls’ High School pupils Willow Lawton and Kaya Avni. “I just can’t stop playing it. Repetitive playing of a song is a trait of mine, and probably all of humanity. I’d like to drive down to Gisborne and meet them. I’m very excited seeing that talent and talking to them.”

Chunn’s time in Split Enz and Citizen Band, and his part in signing Dave Dobbyn’s DD Smash, the Dance Exponents, and managing The Crocodiles, are already covered elsewhere on AudioCulture and in his 2019 memoir A Sharp Left Turn. It was in the early 90s, after his UK sojourn doing office work, that he rejoined Sony Music NZ as its publishing manager. What he knew about publishing – the little he knew, he says – he learnt from wearing so many hats in the industry.

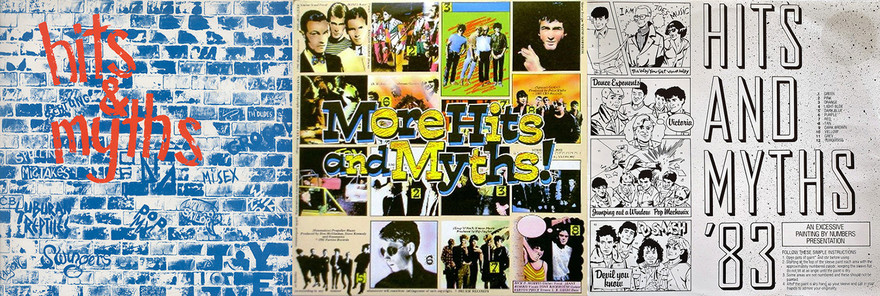

The Hits & Myths series of New Zealand music, compiled by Mike Chunn for his XSF label, 1981-1983

While in Australia for a Sony conference in 1991, he visited Brett Cottle, the longstanding CEO of APRA at its head office in Sydney. Chunn wanted to say to Cottle that APRA wasn’t working in New Zealand: to members and the music industry, it seemed opaque, with poor communication or understanding. Could Cottle help APRA NZ change its ways?

Cottle surprised Chunn by starting the conversation with the news that APRA was about to shift its New Zealand office from Wellington to Auckland, in an effort to increase its communication and rapport with its members and the local industry. “Just a query,” Chunn recalls responding, “Have you got anyone in mind to take over as New Zealand director of operations?”

“Well, funny you should ask,” replied Cottle.

APRA, which opened its New Zealand branch office in 1926, seemed to be a step removed the music-making side of the industry. Visiting the Wellington office in the 1980s did indeed feel like going back to a previous century. The office was wood-panelled, its staff small and reserved, its calculators almost like Enigma machines. It didn’t seem part of the entertainment business, but its purpose was crucial: to receive and distribute royalties from New Zealand radio play, background use, and live performances for its composer and songwriter members, locally and on behalf of international collection agencies. Its main public-facing event, the Silver Scroll founded in 1965, was a private function rather than a community’s celebration of songwriting. Among its creative members, for years those at the art-music end of the business held sway: respected composers such as Douglas Lilburn and Ashley Heenan.

Copyright should serve the creator, and Chunn was determined that APRA’s role be better understood. He turned the Silver Scroll into an event primarily for APRA members, the songwriters. Although each year one song would win the Scroll, the event didn’t share the competitive air of the record industry music awards. New Zealand songwriting and musicians in general were the winners.

When Brett Cottle asked Chunn to consider being the GM of APRA NZ, Chunn replied he’d think about it. He left the room, turned around, and said “I’m in.”

The role had an unexpected benefit. After running through what the job involved, and its goal – “happy members” – Cottle said “Working at APRA, there is total security.”

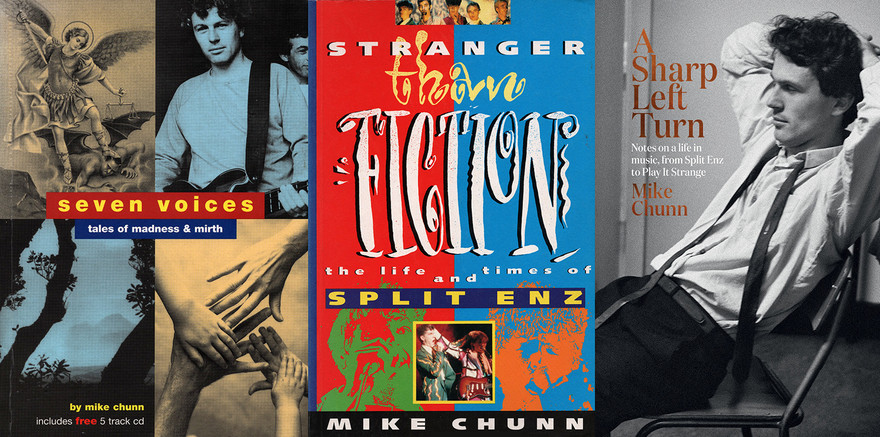

Books by Mike Chunn – Seven Voices: Tales of Madness & Mirth (1997); Stranger Than Fiction: The Life and Times of Split Enz (1992); A Sharp Left Turn: Notes on a Life in Music, from Split Enz to Play It Strange (2019)

Instantaneously, Chunn felt a load lift from his shoulders. As he revealed in his Enz history Stranger Than Fiction, in Seven Voices (a series of autobiographical short stories), and the memoir A Sharp Left Turn, for all his working life – playing in bands, managing them, searching for talent, running a record label – he had never felt security. Going back to Split Enz days, he had been struggling with a “phobic straitjacket”, probably caused by a bad reaction to an LSD trip and strong Thai weed. The term for it was agoraphobia, and it meant he had high anxiety when required to leave Auckland.It was why – much as he loved performing – going on stage caused extreme anxiety. It was why he left Split Enz when they were battling in London, left Citizen Band as they headed to Australia, and froze when required to travel to gigs or meetings, locally or internationally. After years of relying on sedatives when challenged, suddenly his phobia lifted. He felt secure.

Seven Voices (1997) was an illuminating coming-of-age work. Its stories are honest, funny, wistful, and cathartic, and its themes follow those important to Chunn’s own development. It describes an archetypal childhood of team sports and war games in 1950s Otahuhu, the deprivations and obsessions of boarding school, the frustrations of separation from the outside world (Beatles records, local heroes such as Larry’s Rebels, girls), makeshift early bands, the Enz down on their luck (but living a dream) in Ray Davies’s London, the nightmare of agoraphobia, and a return to New Zealand in the late 70s, with Citizen Band (and our cradle-to-the-grave society) about to implode. No experience comes without a lesson that helped shape his personal philosophy and career.

When Chunn took over as APRA NZ’s general manager, and the local office moved to Auckland, he had a team of four. Just one, Rufus McPherson (song-logging “and other mysterious admin things”) came up from Wellington. The only computer was not connected to the internet. Among the first tasks was addressing the use of background music by businesses: as well as radio and television, that meant cafés, nightclubs, fashion boutiques, jazzercise classes at gyms. Although music was essential to these businesses, many neglected to pay the small APRA fee required by law since the 1920s. Some were outraged – there was even a bomb threat, and a complaint to Fair Go – but through patient explanation and visits from an APRA field worker, rather than litigation, most came on board. Personal connections helped, such as when Chunn gathered together an obstinate group of nightclub operators. Chunn’s experience performing on some of their stages meant a conversation could be started, and cooperation followed.

APRA staff at the Parnell Road office, mid-1990s. From left: Lucy Stone, Ant Healey, Donna White, Sophia Cook, Mike Chunn, Greg Clark, Debbie Little, Stephanie McKinlay, Jo Cleary, and Petrina Togi.

He also got the old guard of APRA composers on side; for years at board level, their views had held more weight than pop songwriters, whose work earned the bulk of the society’s income. Chunn visited Douglas Lilburn at home, a bottle of wine under his arm along with a boxset of Lilburn’s electronic works for him to sign. “Afterwards we had a big hug, and I thought, ‘This is will be okay.’” Undoubtedly Lilburn called his trusty sidekick, Ashley Heenan, who met Chunn for lunch. Rather than talk business, Chunn brought up Heenan’s love of croquet – a game of fiendish strategy – “and that’s when anything untoward between APRA and Ashley stopped.” Forming a rapport with people is better than confronting them. “There are no enemies.”

Chunn says he’s always been a team player – he enjoyed rugby and football, not tennis or golf – and that could be seen in the way he ran APRA and Play It Strange. Soft networking is his style, somehow making unlikely connections work for the cause: Sean Fitzpatrick, meet radio exec Steven Joyce; Helen Clark, meet Auckland nightlife legend Johnny Tabla. Diplomatically getting people on side was a skill that helped when dealing with the radio industry, which had often been antagonistic to APRA – which meant tiresome paperwork and besides, wasn’t playing records free publicity? – or politicians disinterested in the disreputable popular music industry.

Chunn found allies in the radio industry – among them, Josh Easby and Larry Summerville – and APRA made things easier for stations’ music reporting logs by suggesting the programmers use a logging tool that was part of the Selector programming software that organises the schedules of music broadcast. With complete logs available, APRA NZ writer-director Arthur Baysting suggested analysing the logs to see which songs were by New Zealand artists. In that way, an accurate percentage of New Zealand music played on radio could be determined.

The answer was 2.9 percent. For every 100 songs played on New Zealand radio, fewer than three of them were by New Zealanders. And the figure was two percent when it just included commercial radio.

At the APRA Silver Scroll Awards in the early 2000s, from left: Mike Chunn, Bill Moran, Arthur Baysting, Brent Eccles (ex-Citizen Band), and Trevor Mallard.

A long-running crusade of persuading, lobbying, and cajoling took place in the 1990s to get more New Zealand music on the radio. There were campaigns – public and behind the scenes – led by the Kiwi Music Action Group, which included Chunn, Baysting, and Brendan Smyth of New Zealand On Air. (This period is described in an excerpt from Chunn’s memoir on AudioCulture, New Zealand Radio in the 1990s: Let the Airwaves Flow.)

His high profile notwithstanding, Chunn, following Cottle’s lead, was determined to keep a back seat on Scroll nights, instead working the room, connecting those who needed to be connected. An exception came in 1998, “the year it all changed,” and he took the stage at the Auckland Town Hall. He explained his approach to the job: he wanted to run an organisation which had happy members. And that meant working on their behalf to improve their lot.

Helen Clark, then Leader of the Opposition, had published a white paper on the creative industries and talked in Parliament about the importance of songs. At a lunch, shadow finance minister Michael Cullen asked Chunn, ‘What does this music industry need to grow?” Once in government, the new Minister of Broadcasting, Marian Hobbs, talked to broadcasters. Chunn has no idea what she said. But in May 2000 it was announced that a New Zealand music content quota was happening; it would be self-regulated via a voluntary code, starting at 10 percent and building to 20 percent over five years. Reaching 20 percent only took four years: to some broadcasting executives, long resistant, lifting their percentage became a point of pride.

The campaign to lift the profile of New Zealand’s songs on its media and among the public had taken a “straddling of worlds and a big force of energy”. There were visits from Irish cultural ambassadors, US songwriters from ASCAP and BMI such as Jimmy Webb and Pat Pattison, and street-level initiatives such as the badges and T-shirts of New Zealand Music Week (which quickly expanded to a month at the suggestion of the then-powerful music buyer of The Warehouse).

A peak moment came in 2001, with the 75th anniversary of APRA. Asking its members to suggest “the best New Zealand songs” led to the 30-track compilation Nature’s Best, which eventually sold over 150,000 copies. It showed Chunn that no matter how well the songs did when released, they had become important to the public. “Commercial legacy bore no relevance,” he wrote in A Sharp Left Turn. Alongside the expected ‘Counting the Beat’, ‘Don’t Dream It’s Over’ and ‘Sway’ were ‘She Speeds’, ‘Jesus I Was Evil’ and ‘Not Given Lightly’.”

APRA's privately pressed 30 Songs compilation (2001), which led to the release of Nature's Best (2002). Far right: the Play It Strange compilation of finalists from the 2004 Secondary School songwriting competition.

Soon afterwards, Chunn spoke to pupils who were about to leave secondary school. When he asked how many of them thought they could write a song, only two out of 250 students lifted their hand. A few months later, he spoke to his daughter’s primary age classmates. He was asked to bring his guitar and show that playing a song “wasn’t rocket science.” It was easier than driving a car, he said, then “How many of you think you can write a song?” All of the children put their hands up.

What changed by the time they were in their late teens, he wondered. A loss of self-belief, a fading of the imagination? Something had to be done. In a recent conversation with Chunn, Bill Moran – an economic adviser to the government – had suggested forming a charitable trust to benefit New Zealand music, of which he was a big fan.

But what would the trust do? Chunn thought back to “those secondary-school pupils who thought they couldn’t write a song [yet] they listen to recorded songs every day of their lives.” No schools taught songwriting, and few teachers had written a song. This could be the trust’s purpose: to encourage songwriting among secondary school pupils. But what to call it? “Play It Strange,” Moran replied, after an obscure Split Enz song, written by Phil Judd.

Chunn’s 11 years at APRA had seen most of his goals fulfilled. It was time to pass the baton, and nurture songwriters at the other end of their craft. After obtaining start-up funding from early donations, and a New Zealand music Telethon, Play It Strange began with a songwriting competition. The prize would be recording time for the 20 songs chosen as the best by a judging panel. In the first year, 150 entries were received, and it has kept growing in the two decades since. Professionally recorded songs have come out on CDs, and another major achievement was having songwriting accepted by the New Zealand Qualifications Authority as part of the curriculum, and an NCEA achievement standard.

Looking back in 2024, Chunn said the songs recorded in 2004 – the first year – had a “naivety” about them. “There was quite a haphazard putting together of melodies, chord structures, lyrics, and all that. And I really believe that now, in 2024, the sophistication of the lyrics and the way they weave them into and around wonderful music, is very exciting. The songs written now reflect a whole new aura of understanding about what makes a song wonderful.”

Mike Chunn with his wife Brigid, early 1990s; and with Debbie Little (of APRA then Play It Strange) and Play It Strange songwriting finalist Lydia Gammie at an event in Hamilton, 2005.

The purpose isn’t for the participants to develop careers as songwriters, it’s about empowerment. In the recording sessions, the songwriters “become giants in that room, and the studio environment has become so much more vibrant than it was.”

As so often happens, Chunn refers back to school days for an analogy, and taps a Sacred Heart alumnus for help. Thinking of Play It Strange songwriting in terms of careers is, says Chunn, “a bit like saying, ‘Surely, if you’re in the First XV at school, you’re going to be an All Black.’ I asked Sean Fitzpatrick once, how many First XV players in a year might become an All Black? He said, ‘One or two’.”

There have been some participants whose early talent is now flourishing – he mentions Louis Baker, Ed Norris, Graham Candy, Annah Mac, Chaii – but the most important thing is encouraging self-belief.

After 21 years, with Play It Strange firmly embedded in the New Zealand music ecosystem, Chunn decided to step aside from running the charity in 2025. “It’s got a momentum,” he says. “For about five years I’ve looked in the mirror and thought, there’s nothing that can stop it or slow it down or kill it.” In 2024, the board asked if he had put any thought into a CEO succession. “I just said, no, I haven’t. But yes, let’s do it.”

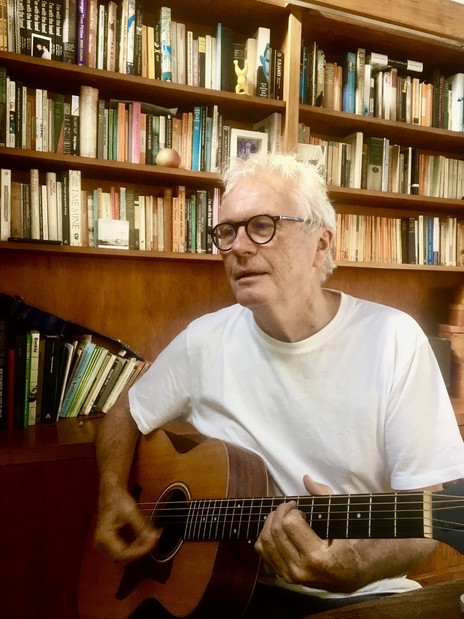

Mike Chunn, 2024. - Play It Strange

There were 98 applications for the job, and the new Play It Strange CEO is Stephanie Brown, from the Dingle Foundation. Chunn will still be involved as an advisor, and he will continue to be part of the judging team. His favourite part of the job has always been listening to the new creations from the fledgling songwriters.

When formulating Play It Strange, and looking for support, Chunn bought a school exercise book and wrote out the philosophy of the intended trust. The formality of a mission statement made him uncomfortable; instead he wrote from within. Part of it says: “The performance and writing of songs, as a natural consequence, can provide huge benefits to many, many people. To witness a child conquering their adversities through the craft of songwriting is a celebration. To hear a class of disadvantaged children playing in a ukulele orchestra is no less so. There is empowerment. There is a beautiful distillation where a young person’s value is realised.”

For so long Chunn, and his community in the campaigns to bring New Zealand music to its public, were voices in the wilderness. Now, the Song dwells among us.

--

APRA Silver Scrolls: Heavenly Pop Hits

Mike Chunn and the 1993 APRA Silver Scroll awards

APRA Silver Scrolls: the musical directors

Play It Strange: a 2005 documentary on NZ On Screen