Acoustic or electric: Bill Lake’s music has worked on alternate currents in the decades since he first appeared on the Wellington blues scene in the late 60s. “There have always been these increasingly divergent paths, but I’ve never let go of either of them.” Despite his passion for acoustic blues, Lake was in demand to contribute electric guitar to blues and R&B bands such as the Original Sin, Capel Hopkins Blues Dredge, and Mammal. (Read: Bill Lake part one, Windy City Blues.)

The 70s would see him work increasingly in a “Pacific R&B” context. Lake had been studying philosophy at Victoria University since his arrival in Wellington in 1967, graduating with honours in 1972. He worked on a doctorate for 18 months; his area was the philosophy of language through texts from Wittgenstein, interpreted by English philosopher Michael Dummett. “He explained Wittgenstein in a way that I’d never seen before, which was really exciting to me.”

Mammal, 1973. From left: Mike Fullerton, Robert Taylor, Bill Lake, Rick Bryant, Tony Backhouse and Mark Hornibrook. - Bill Lake collection

But Lake did not complete his PhD because he found that the academic way of writing philosophy was too constrictive. “I would never find my own voice, my own way of thinking, if I just tried the academic style all the time, where you’re constantly looking over your shoulder at what other people have said.”

Simultaneously, Lake was expanding musical possibilities in Mammal, which featured his underground musician friends such as Rick Bryant, Tony Backhouse, Robert Taylor of Dragon, and Simon Morris of Tamburlaine. The experimental band pushed music boundaries, but was also playing to an audience that wanted to dance. Although Mammal’s music contained elements of blues – which is what attracted Lake to it – he began to write complicated songs from which “you would never guess that I was a blues freak.”

Simultaneously, Lake kept up his interest in more earthly music. Through the 1970s, alongside his study of Mississippi country blues, Lake was immersed in roots and R&B-influenced players such as Ry Cooder and Little Feat. This led to his electric bands of the 80s: the Ducks, the Pelicans, and the Living Daylights, which absorbed these US influences to play original music, mostly by Lake.

An early lineup of the Pelicans, c. late 1982. From left: Andrew Delahunty, Bill Lake, Nick Bollinger, Stephen Jessup. The obscured drummer is Steve Hunt, who left to join Ra and the Pyramids. - Nick Bollinger collection

By 1975 Lake was working as a postie, a day job that lasted several decades. The Windy City Strugglers “mark two” emerged, with Andrew Delahunty, Geoff Rashbrooke and Rick Bryant being joined by a teenage Nick Bollinger on bass. This “semi-electric” version of the Strugglers played a few restaurants and pubs. The manager of the Royal Tiger Tavern on Abel Smith Street hired them “to keep the crowds down” after the long, popular residency of Midge Marsden’s Country Flyers, says Lake. “They wanted something that would bring the heat down. We certainly could have done that.”

Thanks to the matchmaking of counter-cultural music entrepreneur Graeme Nesbitt, in 1978 Lake was tapped by multi-instrumentalist Robbie Lavën to join his band the Red Hot Peppers as guitarist. During this stint in the Peppers – which lasted only three months – Lake formulated a musical approach he wanted to pursue. Partly based on the Curtis Mayfield records of the 1970s, he wanted to form a band that featured acoustic instruments up front, while still having a rhythm section.

Excited, he wrote to his Strugglers cohorts to tell them. “I must have been really hyped up, due to my frustrations in the Peppers,” he says. “And they wrote back saying, Nice idea.”

It took a while to find the outlet, and the songs, to convey his vision.

It took a while for lake to find the outlet, and the songs, to convey his vision.

In 1979 Nesbitt organised Home Grown, a 1979 compilation album of Wellington acts, released by Radio Windy. Lake contributed an original song, ‘Texas Revenge’, on which he was backed by Rough Justice (who also had a rare studio recording on the LP, along with Spats, the Wide Mouthed Frogs and others). “It’s a real cop of ‘Dixie Chicken’ and things like that,” says Lake, modestly.

Midge Marsden was an early champion of Lake’s writing, giving songs such as ‘Blue Murder’ and ‘I Wanna Be With You’ exposure on his 1982 album 12 Bars from Mars. Mike Farrell was the musical director, Lake recalls, “even more obsessed with Little Feat than I was”, which was reflected in the half-time rhythms used.

In the early 80s, putting his passion towards acoustic country-blues to one side, Lake established a band that combined his love for “soul Americana” while performing his original songs which reflected life in New Zealand. As a vehicle to play the songs he had been writing, some with Arthur Baysting, Lake formed The Ducks, a band he describes as amateur – more in approach than experience. Delahunty, who had been part of the jugband/folk scene, was going through a phase of playing raw, Dr Feelgood-style guitar.

The Ducks “grew like topsy, like most of my things do,” Lake reflected in 2018. “Probably when I heard the Hulamen I thought, Oh, this is what we could do. Something electric with a horn section, and really project the songs in a bigger way.”

The Pelicans, 1983. At back, from left: Nick Bollinger, Stephen Jessup, Steve Hunt. In front: Bill Lake, Tim Nees, and saxophonist Peter Famularo. - Matthew McKee

By late 1982 the garagey Ducks evolved into The Pelicans, a bigger, showier bird formed from Lake’s circle of Wellington musicians. The band played original R&B with Little Feat rhythms (‘Shuffleitis’) in songs by Lake that emphasised their locale (‘Banana Dominion’). There was a funky, light-heartedness to the music, but the songs described a society on edge post-Springbok Tour. Besides Lake on vocals and guitar, core Pelicans were guitarist Stephen Jessup, rhythm section Nick Bollinger on bass and Andrew Cross on drums, plus percussionist Tim Bollinger. Jessup and Cross were both ex-Hulamen, as were keyboardist John Niland and brass players such as Dave Armstrong who soon became regulars. Nick Bollinger recalls: “The reason the Pelicans had a horn section was that the Hulamen had broken up, so there were unemployed horn players around. Bill identified with them – their love of funk and soul – though they were younger.”

Early gigs at Cosgrove’s – a back bar of the Cambridge Hotel – quickly drew a regular crowd, many of them from the Hulamen’s loyal audience, others who had, a decade earlier, enjoyed Mammal. One night in 1983, remembers Bollinger, Nick Cave’s Birthday Party was staying at the Cambridge Hotel while the Pelicans was playing in Cosgrove’s. “We were playing our sunny Pacific music, and these dark, tall silhouettes loomed in the doorway, looked in, and left, recoiling.”

The Pelicans’ existence was like a baton being passed back and forth in the timeline of Wellington R&B. As Mark Cubey wrote in TOM magazine, Jessup and Nick Bollinger had grown up seeing Mammal perform, and become part of Rough Justice, which Dave Armstrong and Tim Bollinger had witnessed before their stints in the Rodents and the Hulamen. Local indie label Eelman was on the spot to release this wave of Wellington funk.

Watch: The Pelicans, in an excerpt from a Radio With Pictures special on North Island music, 1984.

Lake was, in effect, a mentor to the Hulamen generation, but he told Cubey how the young band’s exuberant gigs and diverse EP had an impact on him. The Hulamen were “the most immediate sort of influence. I can’t write songs like the Hulamen wrote, but the idea of a band like that … I mean, I was amazed when I saw them, they were the best band I’d seen in ages. And while the Hulamen were occupying the spotlight and a whole lot of musicians I wanted to have in my band, there was nothing for it but to try and organise some songs I’d written, in a very modest way.”

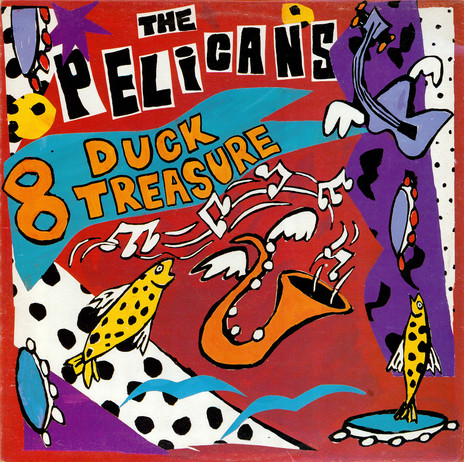

The Pelicans’ 1983 album 8 Duck Treasure was recorded and produced by Tony Burns and Nigel Stone at RNZ’s Broadcasting House studio. Providing strong support was a five-piece horn section; among them Armstrong on trumpet, and Niland on keyboards, both ex-Hulamen, and Callie Blood on backing vocals.

The Pelicans - 8 Duck Treasure (Eelman, 1983); cover design by Debra Bustin.

Rip It Up reviewer George Kay of Dunedin saw 8 Duck Treasure as a standout release in a lethargic year for New Zealand albums. The Pelicans, he noticed, had inherited the Hulamen’s spirit as well as many of their musicians, and their label. “Guided by the dominant presence of guitarist/vocalist/songwriter (invariably political) Bill Lake, they lean towards an easy funk horn-laced feel that allows Lake’s songs to be conveyed naturally. As a singer, he’s no Peter Marshall – more of an untroubled David Byrne.”

It was Lake’s songwriting that made the album special, said Kay. “The best means ‘Shuffleitis’, the loping reggae punch of ‘Banana Dominion’ (listen to the lyrics) and the slow, measured funk of ‘Down to the River’. The rest – ‘Curiosity’, ‘Dead Cars’, ‘Out of the Fying Pan’ and ‘If It Ain’t Easy’ – aren’t too inferior. And this all means the Pelicans have managed to close the Kiwi year with optimism still beating in a few breasts.”

‘Banana Dominion’ got a lot of attention, although it wasn’t a single. “It summed up New Zealand in the Muldoon era,” says Bollinger. “Bill couldn’t help but be political. The song consciously used the Maori strum. It was cod reggae but more than that: cod Pacific reggae. We loved Herbs, and Diatribe. We felt an affinity with their Aotearoa reggae, even though we were from Wellington and all Pākehā.”

In the Auckland Star Colin Hogg enjoyed 8 Duck Treasure’s “sheer good tunes, fine singing, playing, and a lot of style.” Reviewing the band live at the Gluepot, on their first trip to Auckland, he urged readers to catch the last of three nights, “They all have to be back at work in the Windy City come Monday morning.”

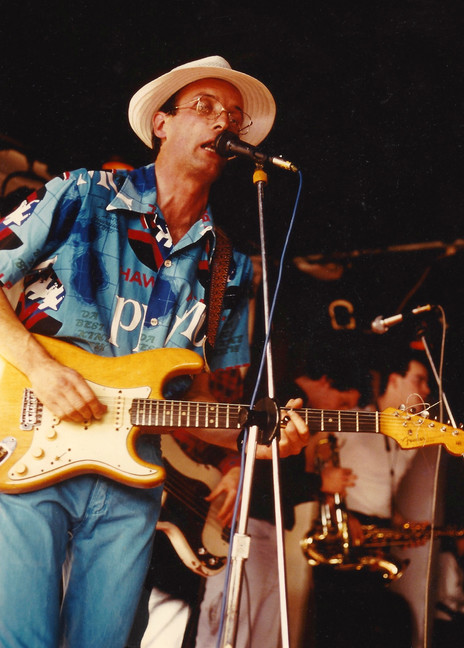

Bill Lake with the Pelicans, 1984 (at right: Dave Armstrong and Andrew Clouston).

The Pelicans were on a roll: 17 years after getting off the boat from Australia, this was Lake’s moment. One night Bruno Lawrence, whose acting career was in the ascendant, told Lake it was time for “us oldies” to “languish in the spotlight”. The band drew big crowds at regular gigs at Wellington’s pub venues Cosgrove’s, the Cricketers and the Clyde Quay, and put any money earned back into the recording kitty for a second album. This approach bought time to polish the album, for which rhythm tracks were recorded by Ian Morris at Marmalade.

Three of the bandmembers (Lake, Nick Bollinger, and Jessup) worked mornings as posties, which provided afternoons for rehearsal and meant they weren’t reliant on the band’s limited earnings. However, it also meant the band’s excursions out of Wellington were limited.

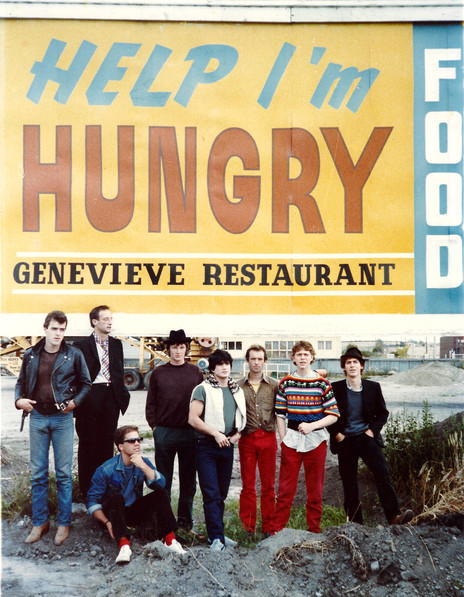

Bill Lake and the Pelicans go hungry in the South Island during their 1984 orientation tour (L-R): Andrew

Clouston, Bill Lake, Tim Nees (seated), Simon Lewis, Nigel Stone (sound engineer), Stephen Jessup, Tim Bollinger, Nick Bollinger. - Nick Bollinger collection

An exception was an Orientation tour in early 1984, which took them as far south as Dunedin, where no posters arrived from the Students Arts Council, so the three graphic artists in or with the band – Debra Bustin, Tim Bollinger, Andrew Clouston – bought a stash of paper and quickly created several dozen posters. (On this and other visits to Dunedin, the Pelicans played incongruous double-bills with The Verlaines and The Orange. A touring busker once appointed himself the support act, then wouldn’t get off stage. The Pelicans had to get up and start tuning their instruments.)

Under a pseudonym, percussionist Tim Bollinger wrote a humorous account of the South Island leg of the Orientation tour for Salient: “Our next gig was Blackball, and we had a long drive ahead of us. Certain members of our troop that, until now, had seemed quite mature and responsible musicians, were already showing signs of roadwear. An undescribable consomme of manic elation was beginning to brew amongst us.”

An unforgettable gig was at Lincoln College, outside of Christchurch. On the dance floor while the band played, several students got on their friends’ shoulders, and spun around like helicopters, while vomiting. “Our accommodation was on the mezzanine above the dance floor, on camp stretchers,” recalls Nick Bollinger. “At 3am we had to go to bed, with the stench of vomit and beer rising up.”

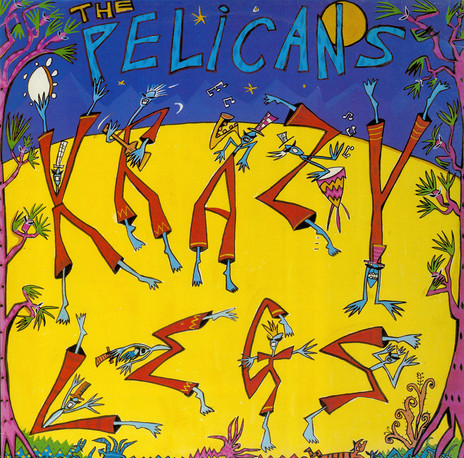

Krazy Legs, a six-track album released in 1984, retained the relaxed feel of 8 Duck Treasure but was a step up in confidence and craftsmanship, with Armstrong and saxophonist Andrew Clouston (fresh from DD Smash) being doubled by the Newton Hoons horn section, Chris Green and Mike Russell. The album was completed at RNZ, once again with Tony Burns and Nigel Stone.

The Pelicans - Krazy Legs (Eelman, 1984); cover design by Debra Bustin.

In a Rip It Up feature, Duncan Campbell wrote, “Krazy Legs is actually a much better record than the rather mixed reviews it’s received would suggest. Certainly it’s derivative (there’s more than one unabashed Lowell George disciple in the band), but the songs are well written, intelligently arranged, and played with plenty of confidence.”

With the Krazy Legs songs, Lake was writing specifically with the Pelicans in mind, or the band worked them up in rehearsal jams. “That’s a much better way to write songs for a band,” says Lake. New Orleans rhythms and Little Feat grooves notwithstanding, the songs epitomised Lake’s soul Aotearoa: ‘Story of a Love Affair’, ‘Krazy Legs’, ‘The Big Picture’. While still sunny, Pacific music, songs such as the Carribean-inflected ‘Path of Least Resistance’ reflected the anxieties of early 80s New Zealand.

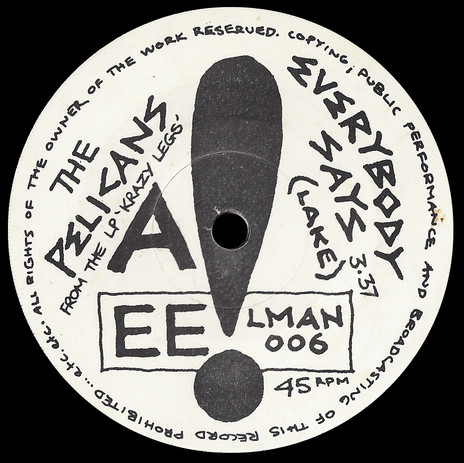

Pelicans - Everybody Says (Eelman 45rpm single, 1984)

The relative speed with which Krazy Legs appeared after 8 Duck Treasure worked to its advantage. The album’s title track, plus ‘The Big Picture’ and ‘Everybody Says’ were written soon before the sessions began, giving their recordings a freshness. ‘Working’ and ‘Path of Least Resistance’ were popular at gigs. ‘Working’ had a Dr John feel in its bassline bed, and rich backing vocals; ‘Path of Least Resistance’ was underpinned by joyful steel drums, strutting New Orleans bass, and stabbing brass, with a spoken playlet in the middle eight.

During this period, the Pelicans stretched out, backing saxophonist Andrew Clouston on his only solo disc, the 12" instrumental EP The Bag (Funky Barp), on Eelman. Among the tracks was Allen Toussaint’s ‘Freedom for the Stallion’.

After ‘Krazy Legs’ the band had a “winter of discontent”.

Despite the upbeat disposition of The Pelicans – reflected in Lake’s Hawaiian shirts and the bright folk-art album covers and videos by Debra Bustin – after Krazy Legs the band had a “winter of discontent”. Cold rehearsal rooms and a lack of forward momentum meant the edge was wearing off, recalls Lake. “I just got this feeling that people weren’t very happy doing it any more. So I just said, let’s flag it. Natural death. There weren’t any big arguments about it, I guess everybody felt the same.”

Lake regrets that he didn’t have the drive to write more songs and go on the road more often. Organising gigs wasn’t his strength, and the musicians’ availability was limited. “Also, I’d come to feel that electric bands weren’t quite my thing, especially bands with horn sections.”

Within two years, another band appeared: Bill Lake and the Living Daylights. They were like a stripped-back version of The Pelicans, and flightless by choice. Lake and Bollinger remained core members, and other players included singers Ra Te Whaiti, formerly of the Pyramids, and Martha Samasoni, ex-Netherworlds saxophonist Neville Schwabe, pianist Alan Norman, and in-demand drummer Ross Burge.

A residency at the Oaks Tavern on Manners Street suited the Living Daylights’ modest ambitions. “We work on a different principle from the Pelicans,” Lake told me in late 1987. “Even though they weren’t pushing terribly hard for success, we did have a vague idea that we might become something. It sort of grew into something that people took seriously, and we took seriously. I don’t really like getting into that syndrome, but you get to a point where you do these gigs and make a huge investment, risk your all, and maybe make $100. Playing a place like the Oaks, you’re paid a fee and don’t outlay any money. The cost of it is you don’t become a well-known band.”

Like the Warratahs – then emerging from the Cricketers with their debut album – the Daylights found a happy medium, a regular gig that enabled them to play mostly originals and still keep a crowd happy.

While Lake had become an assured frontman, he was keen to see his songs performed by stronger singers: Te Whaiti had a great voice and charisma, and when he left his temporary replacement was Patrick Lenniston. Standouts in the Living Daylights were the saxophonists: Schwabe, who left to briefly join Ardijah, and then James Daniels. Both managed a classic rock’n’roll feel (‘Dance Crazy’), while having serious jazz chops.

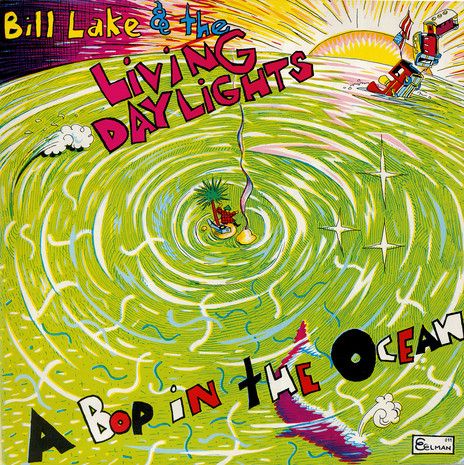

The Living Daylights’ album A Bop in the Ocean had more spontaneity than the Pelicans’ perfectionism, and the R&B couldn’t help but show through. Regular playing at the Oaks meant constant overdubs could be avoided: it was possible to record live in the studio to a high standard.

Bill Lake and Living Daylights, 1988. From left: Alan Norman, Ed Ware, Bill Lake, James Daniels, and Nick Bollinger. - Nick Bollinger collection

Produced by the Daylights themselves, with help from Tim Farrant and Fane Flaws, the use of space and R&B recording techniques emphasised the band’s vocal strengths. Lake’s songs (the ballad ‘Defrost Your Heart’, the rug-cutting ‘Good For You’) were written with strong R&B vocalists in mind – and the BVs came from gospel – but the songs were uniquely Lake’s, despite the stew of influences. “I think about this a lot,” said Lake. “When I come up with a piece of music, I hear all the antecedents myself. ‘This sounds like …’

“Arthur’s always saying, ‘Forget that, just do it.’ Because it’s going to turn out different, and it usually does. You can’t eliminate it. The only stuff I listen to is black music, from blues to the present day, and that’s the way I want to write.”

Bill Lake & The Living Daylights - A Bop in the Ocean (Eelman, 1987); cover design by Tim Bollinger.

Just to confuse the Wellington R&B tree, the Daylights – with A Bop in the Ocean out on Eelman – was thinking of morphing into two bands: one to play covers, the other for Lake’s originals. They were aware of the pitfalls, of working hard to become proficient and finding a unique voice – only to find the audience has moved on. “I suppose we are a bit anachronistic,” Bollinger said of the Daylights, “but music does keep coming round in cycles.”

Instead, in the 90s into the 2010s, Lake and his divergent paths – acoustic vs. electric – would find an outlet with his oldest musician friends, in a revival of the Windy City Strugglers. The group would see Lake return to acoustic guitar for big-band roots music, while also recording solo albums playing original blues written on Wellington’s south coast.

--

To be continued: home truths and Windy City struggles