A prominent New Zealand blues guitarist – of the electric variety – once told Bill Lake that any local blues players were lying if they didn’t admit they learnt about the blues from John Mayall. For New Zealand teenagers who came of age during the heyday of The La De Da’s and The Underdogs, that may well be true. But Lake demurred, albeit to himself.

Slightly older, Lake’s experience was different. He became interested in the late 1950s, when the blues revival was a subset of the folk revival. When it was de rigeur for some left-leaning parents and their hipster offspring to include in their collections – alongside major-label folksingers such as The Weavers and trad jazz by the Chris Barber band – the odd blues disc by the likes of Josh White and Big Bill Broonzy. Also, Lake grew up in Australia where, he thinks, more records from the United States were played on the radio, whereas in New Zealand there were local bands covering British bands playing the blues (and pop).

Arriving in Wellington in 1967, Lake quickly found musician friends with a taste for blues.

When he arrived in Wellington in early 1967, aged 19, Lake quickly found a group of musician friends who had deeper roots than the Rolling Stones and Mayall, though they were happy to cover their versions of R&B in their fledgling bands. Among them was Rick Bryant, whose parents were jazz fans and whose listening diet after the lights went out was the hip R&B programme of Cotton-Eye Joe (aka Arthur “Turntable” Pearce) on Wellington’s 2YD. On the folk scene, performers such as Max Winnie and Colin Heath were older and had made a study of blues roots. The scholarly approach of these players – and Pearce – laid the groundwork for Wellington’s dedicated and informed diet for the blues.

Lake’s education in roots music began in Canberra, where his father was with the national library. “My parents were liberal, not to say fellow-travelling people,” he says. “Their musical taste tended to be folk music. I heard The Weavers, but we didn’t have the black end of the folk spectrum: I can’t remember a Josh White record, for example.”

In 1955 – when Lake was eight – his father was posted to Britain for three years. By 1957 Lonnie Donegan was in the hit parade and on television with his own genre, skiffle. “I still have the 10-inch LP, and it’s still really good. He was doing American folk music and blues, rather than the novelty records which made him famous”. On BBC television – in Australia the family didn’t have one – Lake saw the pioneering rock’n’roll programme Six Five Special, which featured Cliff Richard and the Shadows “which was pretty good”, and Lord Rockingham’s ‘Hoots Man’, a big-band instrumental led by a saxophone playing R&B solos. Through Donegan, Lake heard Lead Belly and Lonnie Johnson. “I was intrigued by that. By this time I was 12 or 13.” At the same time, Lake liked Elvis and Little Richard “in that period they talk about as the ‘dead’ period of rock’n’roll”: his sister was a fan of Bobby Vee, who was hired to front Buddy Holly’s Crickets after the plane went down.

At Sydney University, Lake’s older brother Sam was hanging out with bohemian friends who were playing Lead Belly and Lightnin’ Hopkins records. Sydney University was a hotbed of slightly older intellectual talent such as Germaine Greer, Clive James and Richard Neville.

When Lake first picked up the guitar, aged 14, it was a nylon-string model which quickly changed when he realised his heroes played steel strings. A guitar teacher organised by his father was a jazzer who immediately realised Lake was into a more basic approach. “I was much too primitive to learn what he had in mind. He asked what I liked, and when I said acts such as Lightnin’ Hopkins and Lead Belly, he said to my father, ‘I don’t think I can save this guy.’ Obviously I was never going to be a jazzer. I couldn’t relate to jazz chords at all in those days.”

Lake never discussed his his passion for music with his parents; his father was tolerant, and liked The Weavers, so “must have thought, well that’s not that far removed.” Decades later, when he sent his mother an album he made with The Pelicans, she said, “Well, at least the words aren’t stupid.”

Other than that, his parents were non-committal. What they were keen to see was Lake going to university. His mother had missed out, and his father – the son of a teacher at Bendigo’s school of mining – was the only member of his family able to reach the tertiary level.

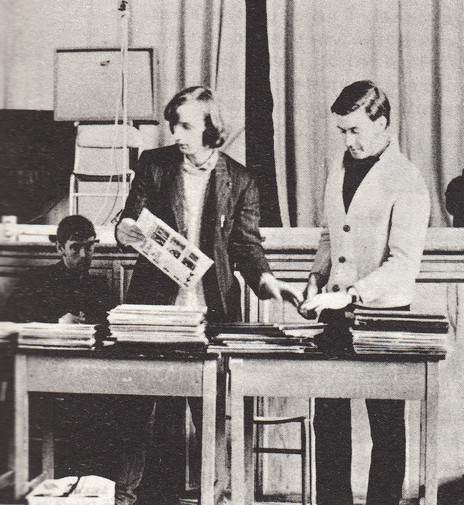

Blues 101 at the National Folk Festival, 1969 with, from left, lecturers Colin Heath, Bill Lake and Max Winnie

Lake’s brother Sam had already gone to the Australian National University in Canberra, and often went “down” to Sydney to mix with the creative bohemians. “He knew Germaine Greer, some of those people. It was a network.”

It was Sam who introduced Lake to Bob Dylan. “We slept in bunks, and one night he brought home some mates. I was trying to sleep, and they put on a reel-to-reel tape of what turned out to be The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.” On the other side was a woman with a high, pure voice. Lake was more taken by her voice than Dylan’s, so when his next birthday came around, he asked his father for one of her albums. He didn’t know that her name was Joan Baez.

The doors were opening, helped along by the books of early blues scholars such as Samuel Charters and Paul Oliver: proselytisers whose works are still on Lake’s shelves today. He began buying mail-order albums from a Melbourne shop: Lead Belly, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, on the Folkways label with thick vinyl and booklets of information inside. When Lake was about 15, his brother was in the UK studying for a PhD, and sent him the odd album: The Best of Muddy Waters, The Best of Little Walter.

“I was delving more and more into acoustic country blues. I had a sub to Sing Out [a US folk magazine], and its advertisements were enticing. It was a time when reissues of old stuff was coming out. Before Yazoo there was the Original Jazz Library: they put out Charlie Patton, Mississippi blues, all this stuff. I was revelling in it, trying to do it.”

The young blues scholar enjoyed the Rolling Stones as much as any reader of ‘Go-Set’.

But the young blues scholar was fully aware of the Rolling Stones, enjoying their early country blues original ‘Good Times Bad Times’ as much as any reader of Go-Set. He didn’t get to see any of the British invasion acts in person, though there was a Canberra group that imitated the Stones called the Bitter Lemons (their front man Paul Lyman later became famous as a TV host). “They were good musicians, but just a covers band: not as original as [Christchurch’s] Chants R&B.”

Nevertheless, Lake admits, “I was quite purist about it.” The scholar is never too far beneath the surface, no matter how original his songs would eventually become. With his closest friend in Canberra, Gilbert Burgoyne, and another guitarist, Lake formed a jug band in about 1965, soon after leaving school. They learnt several songs from the recently released Jim Kweskin Jug Band album, eschewing Kweskin’s vaudevillian tendencies for the straight blues numbers. “We did incompetent versions of those and got a residency in a pub that lasted three weeks. We had no PA – it was completely acoustic. Gil had a jug, and I played harmonica and mandolin. The other guy sang and played kazoo – I’ve been allergic to it ever since.”

The band practised more than it performed, though once its members were recruited at a pub by the prominent Australian artist John Percival, who gave them £5 to come back to his place and play at a private party. Lake realised his limitations when he went to a suburban dance in Canberra – with a real band – and his friends pushed him on stage to play lead guitar on The Shadows’ (typically cautious) instrumental ‘The Rise and Fall of Flingel Bunt’. “I couldn’t. After half a bar I lost it. I was very drunk but I didn’t know how to play in public, especially not with a band.”

In 1965 Lake enrolled at the Australian National University to do a double major in law and the arts. “But I had never learnt how to study on my own, and I failed the lot at the end of the year.” He got a job at the Government Printing Office as a pay clerk, and at the end of 1966 he and Burgoyne had the idea “of going bohemian in Canberra. This was quite hard: it didn’t have anywhere you’d call a slum. There was one famous place, the Causeway: a legendary dump. But I never went there.”

Lake went flatting in the suburbs and rehearsed. “After three months, I was a bit sick of it. Then, the guitarist in the jug band said, ‘How would you like to go to New Zealand and avoid the draft?’”

Although Lake had been on protests against the Vietnam War, dodging the draft was more a bonus of coming to New Zealand than the real motive, for him or his guitarist friend. The guitarist was chasing a girl, the daughter of the New Zealand trade commissioner, who had returned home. Lake knew he might be drafted at 20, but emigrating “just appealed to me.” Although the initiator bailed on the idea, another friend – “also chasing the same woman” – joined a gang of four who boarded the MS Achille Lauro heading for Wellington. “This other friend had actually been called up. He was 20, and as I recall there were voices over the Tannoy on the wharf saying, ‘Owen O’Brien, please report …’ He didn’t, of course, and we stayed low and we got away with it.”

(Lake later heard from his father that half of all birthdates in Australia were drafted to do compulsory military training, and draftees could be sent to Vietnam. Whereas in New Zealand only a third of all birthdates were called up for three months of CMT, and conscripts had to volunteer to go to Vietnam.)

The Achille Lauro steamed into Wellington harbour in February 1967, past a pod of dolphins; the day was sunny and warm. While Lake’s first impressions of Wellington may have been atypical, the welcome wasn’t, and he has lived in the city ever since.

Lake and his friends slept on the floor of the alluring girl’s flat. He had brought with him two large boxes of blues LPs which were soon pored over by the local aficionados, starved of the real thing. Lake quickly met like-minded friends, at the upstairs bar at the St George Hotel, and the Balladeer folk club further up Willis Street. (By an odd coincidence Frank Fyfe, the Australian expat who started the Balladeer, knew Lake’s father.) He began playing harmonica with Paul Tolley at the Balladeer, and accompanying other singers on guitar.

In mid-1967 Rick Bryant asked Lake to audition for the Original Sin, a fledgling R&B band that also included Simon Morris, Rod Bryant, Aff Fraser and Norm McPherson (a drummer who played standing up). “It was all Pretty Things, Stones, the odd Bo Diddley song, ‘Gloria’, that bunch of songs.” But the aspirant R&B performers didn’t get all their tips from the British invasion. “As a teenager Rick listened to a lot of jazz and Cotton-Eye Joe – he knew a lot about American music.” Other Wellington aficionados included Andrew Delahunty and Max Winnie.

The most scholarly of all the local blues buffs was Colin Heath, says Lake. A big record collector – of 78s as well as LPs – he was trad jazz fan “who made the switch. He was about 30 when we were 18.”

Lake began playing with a group of friends forming a jug band: Geoff and Mike Rashbrooke, Cathy McGrath, Lindy Mason, Steven Robinson, Simon Morris. They gathered in a flat on Kelburn Parade, near the university, and had a group audition for a Jim Kweskin-style jug band. “More leaning to the vaudeville side of it, but with guitar players, harmonica players – people who could actually play and arrange. But although that side of it appealed to me, Geoff and I immediately thought, ewww, we don’t like this inauthentic stuff. We want to do proper blues, proper jug band music, which we had already heard. I don’t know whether that’s where the Strugglers started, but that where the stream began.”

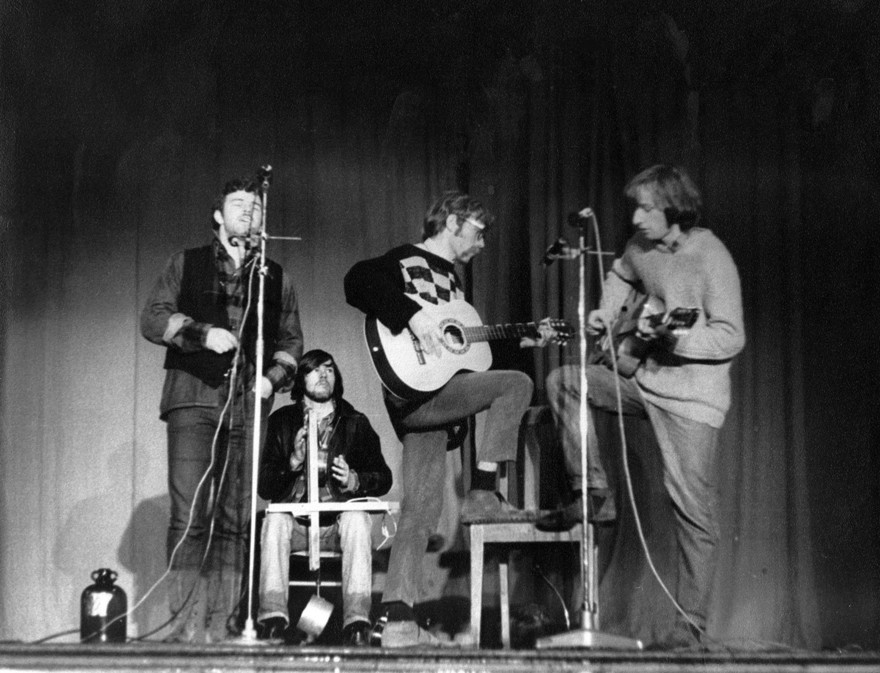

Windy City Strugglers, at the National Folk Festival, Wellington, 1969. From left: Rick Bryant, Mike Rashbrooke, Geoff Rashbrooke, and Bill Lake. - Nick Bollinger collection

The Windy City Strugglers first played in March 1968 at the National Folk Festival in Wellington. In the group were Lake and the Rashbrooke brothers; Rick Bryant joined shortly afterwards. He and Lake were in Original Sin together, Bryant was also in Gutbucket, and Mammal began to form the following year.

The folk denizens at the National Folk Festival were a little taken aback by Wellington’s fledgling jug band, taking its lead from Memphis in the 1920s. “Geoff took great pride – and Rick did too – that, as people who played real blues, we were out of place in the folk scene, which consisted of Dylan, and a lot of English folk.” While the folk scene was eclectic, its preference was for the British variety and its virtuoso guitarists such as Davy Graham, Bert Jansch and John Renbourn. Female singers enjoyed performing in the style of Judy Collins (who visited Wellington’s Monde Marie in the late 1960s).

“There was a version of blues from people such as Max Winnie and Val Murphy: it was definitely blues, but it wasn’t back in the 20s like us, it was probably based more on Josh White, Big Bill Broonzy, and Brownie than what we were about. In a way we didn’t fit in.”

Ground zero for the city’s counterculture was a bar in the Duke of Edinburgh, a pub on the corner of Willis and Manners Streets. (In 1964 the Beatles looked down upon it from the balcony of the St George.) It was a home for bohemians, the artistically oriented “… and criminals,” says Lake. The public bar was on the corner, and while some of its “rougher” patrons strayed into the artists’ bar, the traffic didn’t go the other way. The cultural clientele was “mostly students, a few journalists, and probably musicians like Bruno who weren’t actually students but hung out with them. Geoff Murphy. A certain kind of petty criminal element, who were also bohemians. Some had jobs but they would have taken their tie off to go to the Duke.

“We drank and smoked and talked a lot. Because I primarily hung out with the musicians I knew: Jeff Kennedy, Simon, Rick, some others, and people very interested in music. That was who I mixed with, I didn’t even mix with Bruno. I knew who he was, but I didn’t really talk to him because he was older and in the jazz scene.”

Afterwards, there would be parties in nearby, rundown flats on streets such as McDonald Crescent, location of squats, an urban commune and James K Baxter’s ‘Firetrap Castle’. Janis Joplin and Rolling Stones on the turntable, over and over, flagon beer and, occasionally, “really horrible wine”.

The windy city music scene in which Lake was moving was underground, almost oblivious to the promoters putting pop acts in the clubs and getting them recorded at HMV on Wakefield Street. To the promoters, it was an industry, an income.

“We had nothing to do with that whole scene. But there were gradations. Even in the blues/R&B spectrum, we were at one end, the rough end, and then there were people who were much better players than us, and bands who played really well.” Among them was John O’Connor of the “wonderful” Supernatural Blues Band, Chris Seresin of Steampacket, and Milton Parker of The Relics. “Milton reputedly described the Original Sin as ‘cavemen’,” says Lake. “Which we took as a compliment!”

The Original Sin was uncompromising; Roger Watkins describes the group as giving the impression “everything could collapse into utter chaos at any moment. In a way, Original Sin became the patron saints of the numbers of revolting, also-ran R&B groups of the time.”

Original Sin, Battle of the Bands, Lower Hutt, 1967. L to R: Rick Bryant, Norm McPherson, Rod Bryant, Aff Fraser, Simon Morris, Bill Lake. - Buchanan Studios/Rick Bryant collection

The mix of Chicago blues, and “meandering originals” did attract the students, though, and they appeared at the Hard concerts at the university, and at the Mystic. This club was like an offshoot of the Duke, run by a regular called Tom Shorrocks. An “incredibly energetic” Liverpudlian who jumped ship in Wellington,Shorrocks created the Mystic in an unused space on Willis Street 100 metres from the Duke: upstairs, bare floorboards, bring your own under your coat. The Original Sin was “sort of the house band” at this casual place, which later moved to Tennyson Street next door to Club 25, the premises of a motorbike club “with a bit of a reputation.”

They were all the same, these venues, says Lake. Opens spaces above empty shops. “We’d rent them out and play, people would dance and drink. With 10 o’clock closing you needed somewhere to go afterwards.”

Lake’s slide guitar playing can be heard on 'Work Song', recorded by the Wellington’s Capel Hopkins Blues Dredge led by pianist and vocalist John Hannan. It appears on the 1970 Ode compilation of Wellington blues acts, In the Blue Vein.

Bill Manhire once described Wellington as a boutique city. The weather is often hostile, which drives like-minded people indoors to create. Roger Watkins picks this up when describing Gutbucket in his book When Rock Got Rolling: the Wellington Scene, 1958-1970. “By its very nature, blues lends itself to the pastime known as jamming. This is great fun for participants, but it can be confusing and tedious in the extreme for onlookers.

“So it happened that quite often with Rick Bryant out front hollerin’, and Bill Lake huffing and puffing on an assortment of mouth-organs. Then the next night you might go and watch Original Sin, or Mammal, or Capel Hopkins perform, and see the mighty sweating and vein-popping Rick in tandem with the wailing Bill fronting any of them. This was Rick and Bill jamming with everyone, a situation quite acceptable to all concerned.”

And so it would prove, over the next 50 years.

--

Read more: Bill Lake in Mammal, the Pelicans, and the Living Daylights