New Zealand can’t claim to have produced any of the world’s biggest blues stars. We are 12,000 kilometres from the music’s Mississippi birthplace, and even further from the scene of its adoption in the London clubs of the early 1960s.

But we have bred our own blues men and women. Midge Marsden, Marg Layton, Hammond Gamble, Darren Watson, Rick Bryant, Coco Davis, Bullfrog Rata and Jan Preston are just a handful of New Zealand names known for their convincing and individual interpretations of the blues.

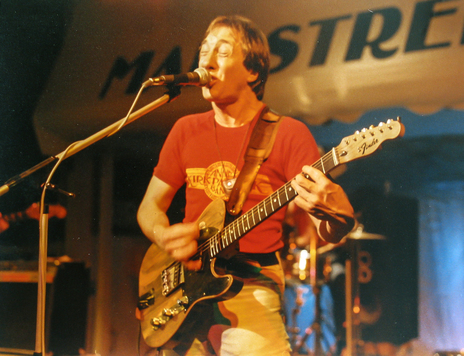

Midge Marsden at Mainstreet in the late 1970s

No one will ever know who sang the first blues, but the first commercial blues recording was made in New York City in 1920, by the vaudeville singer Mamie Smith. By the end of that decade, blues were being recorded in all manner of styles, from the sophisticated arrangements of big bands such as Duke Ellington’s Orchestra to the rowdy guitar and vocal exhibitions of Mississippi blues man Charley Patton.

It is highly unlikely that any of Charley Patton’s 78s ever found their way to New Zealand. Until the 1960s, these were barely heard outside the black communities of the American South. But local listeners would soon become familiar with the blues and its distinctive 12-bar form. In the mid-1920s, the Australian dance band Linn Smith’s Royal Jazz Band, whose repertoire featured such titles as ‘Bow Wow Blues’, paid several visits to New Zealand. Local jazz bandleader Epi Shalfoon, who in 1930 made what is believed to be the first New Zealand jazz recording – for a promotional film – was noted as a good blues pianist.

Epi Shalfoon at the piano, jamming with his band at the Auckland Swing Club, 1947. From left are Bob Griffith,

Nolan Rafferty, Dale Alderton, Frank Gibson and Albie Parkinson - Shalfoon family collection

After World War II, the jazz audience grew. For the jazz connoisseur, a working knowledge of the blues was seen as essential to an understanding of the music’s roots. A 1959 “foundation list” of “50 Basic Jazz Records” in the New Zealand Listener included recordings of Muddy Waters, Blind Willie Johnson and Lead Belly – classic examples of Chicago Blues, gospel-blues and folk blues respectively.

Folk fans too recognised the blues as a tributary of the music they loved. Folk had seen a widespread revival from the late 50s, led by the charismatic and political American singer/banjo player Pete Seeger. Record collections of New Zealand folkies would often contain discs by blues artists like Josh White, Sonny Terry and Lead Belly. The well-publicised left-wing sympathies of these performers added to their credibility in the folk world. When White visited in 1965, he was given a post-performance party at popular Wellington folk venue and coffee bar the Monde Marie.

The Monde Marie - Courtesy of the Wellington City Council Archives Ref: 00138_0_10188)

Though the jazzers tended to look down on the folkies, regarding their music as unsophisticated, the occasional musician would cross the folk-jazz divide, such as Wellington’s Max Winnie. Known in the folk scene for his beautiful voice and eclectic repertoire, his broad musical appreciation led to a stint playing banjo and guitar with local Dixieland band The Valley Stompers. For Winnie, the common denominator between folk and jazz was blues.

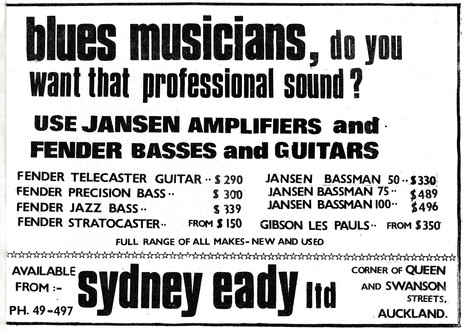

A Fender guitar through a Jansen amp: Sydney Eady Ltd advertises in Blues, issue #2, 1969

When the British beat boom struck in the mid-1960s, blues songs entered the repertoires of countless local bands, though many of the musicians barely realised the origins of the music they were playing. Distinguishing themselves from the more commercial (and less bluesy) sound of The Beatles, groups such as Invercargill’s Unknown Blues, Christchurch’s Chants R&B and Auckland’s The Underdogs gravitated to the rougher music of The Rolling Stones, The Pretty Things, The Animals and Them, which had in turn been learned from black American blues artists.

Taranaki’s Bari & The Breakaways recorded versions of Big Joe Williams’ ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’ and John Lee Hooker’s ‘I’m Mad Again’, secondhand blues songs picked up from recordings by British groups Them and The Animals respectively. Looking back, Breakaways’ rhythm guitarist and harmonica player Keith ‘Midge’ Marsden admits he had no idea who the songwriter credits “Williams” and “Hooker” referred to. “I didn’t even know they were black,” he says, marvelling at his own naivety.

By the time the Breakways broke up in 1967, Marsden had become curious about those songwriter credits. British blues bandleader John Mayall was promoting the music with an almost missionary zeal, drawing attention to its black origins in articles, interviews and liner notes and making converts like Marsden aware of the blues as a genre in its own right, not just a tributary of British beat music. Many others took up the cause.

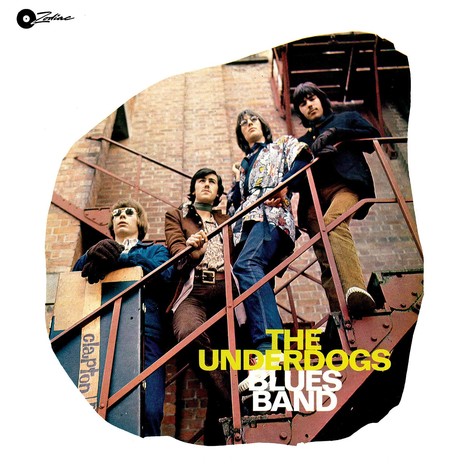

The Underdogs’ classic debut album, released on Zodiac in early 1968

Mayall’s group The Bluesbreakers spawned a series of highly influential blues-based musicians who would go on to form bands of their own, notably Eric Clapton with Cream and Peter Green with Fleetwood Mac. In the wake of Mayall, local bands began to identify themselves specifically as blues bands: The Original Sun Blues Band (Auckland), The Supernatural Blues Band (Wellington), The Bernard Jenkins Blues Band (Christchurch).

When The Underdogs, who had begun in 1964 playing a mixture of R&B, soul, rock’n’roll, released their first album in 1968 it was titled The Underdogs Blues Band. (These bands, for the most part, still modelled themselves on the British rather than the black American blues bands. In the Underdogs’ cover photo, the name “Clapton” is tellingly inscribed on a guitar case, in a font remarkably similar to that used on Mayall’s self-designed album covers.)

Also in 1968, Original Sun guitarist Alastair Riddell and disc jockey Selwyn Jones mounted a National Blues Convention at Moller’s Farm in Oratia, Auckland. The success of the weekend-long outdoor festival spawned a second, larger event the following year.

Alastair Riddell at Battle of the Bands, 1968

Among the groups who brought their blues to the Conventions were Auckland’s The Killing Floor led by guitarist and blues connoisseur Henry Jackson, Wellington’s Capel Hopkins Blues Dredge led by pianist and vocalist John Hannan, and Gutbucket – a New Plymouth-via-Wellington quartet, who featured the vocals of Rick Bryant, a 19-year-old singer from the capital, with a prematurely weathered and convincing voice. These groups showed they had been listening not just to white blues interpreters like Mayall and Clapton, but also to contemporary black blues artists such as B.B. King, Buddy Guy and Junior Wells, whose records had begun to be released in New Zealand.

Advertisement for the Second National Blues Convention, Moller's Farm, Oratia, 27-28 December 1969. From Blues, issue #4

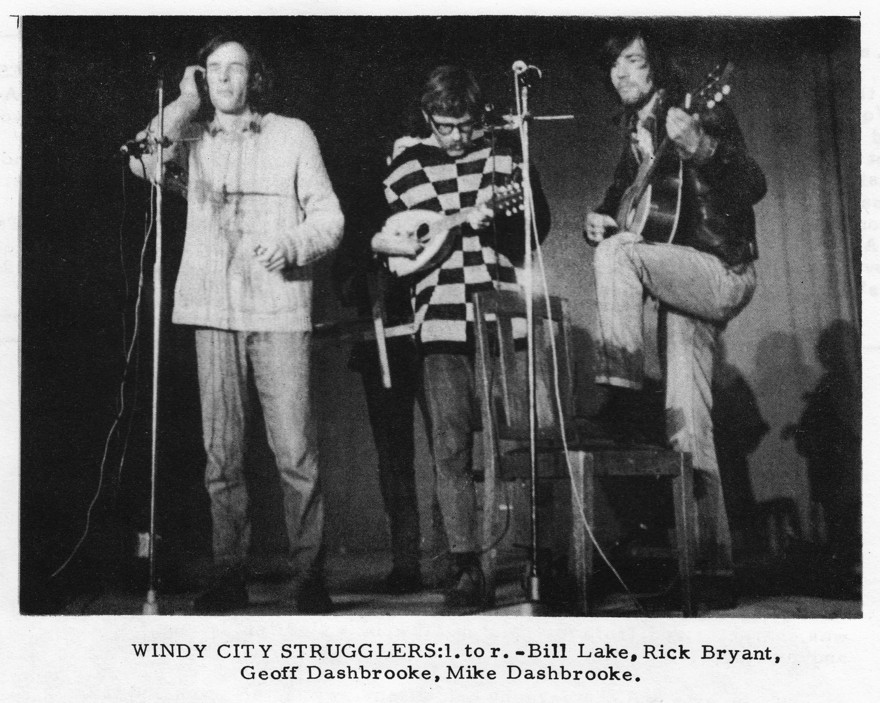

Another feature of the Blues Conventions was a number of acoustic blues groups, including The Mad Dog Jug Jook and Washboard Band and The Greasy Handful (both from Auckland) and Wellington’s Windy City Strugglers. These groups were all variations on the jug band: a pre-war, African-American tradition that mixed blues with vaudeville and medicine show routines. The repertoires of the local jug bands were learned partly from contemporary (and white) American groups such as The Jim Kweskin Jug Band, and partly from collections of 1920s and 30s recordings, which were now appearing on LPs by specialist labels like Folkways and Arhoolie.

Windy City Strugglers, August 1969. From left: Bill Lake, Rick Bryant (obscured), Geoff Rashbrooke, Mike Rashbrooke. They are performing at the 11th annual New Zealand Universities Arts Festival, held in Dunedin.

The Windy City Strugglers were led by Bill Lake, a guitarist, harmonica player and singer who had recently moved to Wellington from Canberra to avoid conscription, bringing his collection of jug band and early blues reissues. Another notable jug band of the period was Christchurch-based Band Of Hope Jug Band. In 1967 their recording of ‘Downtown Blues’, originally cut in the 1920s by Memphis jug band musician Frank Stokes, was released as a single for Kiwi Records, followed by a couple more singles and, in 1968, a self-titled LP.

Mad Dog Jug Jook and Washboard Band, at the National Folk Festival, held at the Wellington Polytechnic, October 1969. From left, Tom Crannitch, Robbie Laven, Andrew Delahunty, Pete Kershaw, Chris Grosz. Besides concerts by many different local acts, there were lectures and workshops, some of which got diverted into discussions about whether white musicians could play the blues

Unlike the electric blues bands, the jug bands found tacit acceptance in the folk scene. The Strugglers, Mad Dogs, Greasy Handful and Band Of Hope also played at folk festivals around the country, as did solo performer Alan Young, who developed a specialty of playing bottleneck style on a National Steel guitar.

Blues 101 at the National Folk Festival, 1969, with lecturers Colin Heath (obscured), Bill Lake and Max Winnie

John Hannan and Colin Heath take part in a jam session at the National Folk Festival, October 1969

At the 1969 National Folk Festival in Wellington, Bill Lake, Max Winnie and double bass player Colin Heath (a British-born jazz musician whose tastes, like Winnie’s, ran to the blues) hosted workshops based around blues recordings, while Australian-born Frank Povah demonstrated the blues guitar techniques he used to accompany his singing. Povah would have an influence on the young Rick Bryant. “Frank was a no-nonsense, big voice blues singer, and he showed me the way”, he says. “He did a reading of ‘My Baby’s Rocking Me With a Jelly Roll’ that became my starting point as a dirty blues singer. He had just the right amount of gruff and gravel for the song, which requires them.”

Val Murphy at the National Folk Festival, Wellington, 1969

Meanwhile a few folkies were crossing the tracks. Val Murphy, a powerful folk singer from Levin who had made two mid-60s albums in the Joan Baez vein for HMV, declared her conversion in the first issue of Good Noise, a cyclostyled blues magazine edited and published by Wellington record retailer Colin Morris. “I began to see folk music as sweet and sugar coated,” said Murphy. “I don’t know when I discovered blues, but folk lost its meaning and blues said it all.”

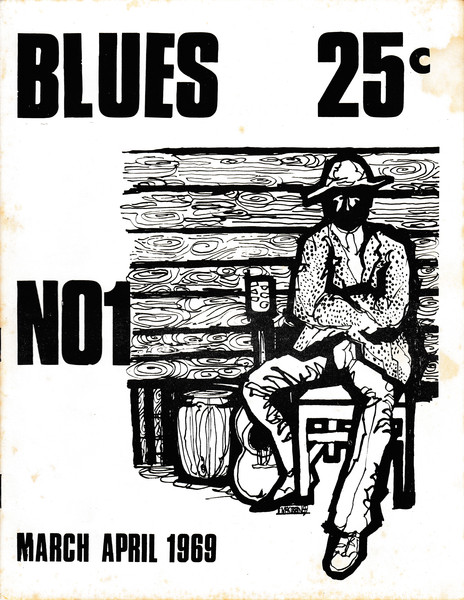

In Auckland, teenage blues aficionado David Colquhoun also launched a blues magazine, Blues. Like Good Noise, it combined essays on the history and practitioners of the music, reports on local blues acts and events, and opinion pieces with a stern and proselytising tone. “Musical apathy must be eliminated quickly so please fight for this music,” concluded an essay on the local blues scene by Henry Jackson. The magazines purveyed the notion of blues as a pure and authentic musical expression, in contrast to commercial pop, which was heavily scorned by some of the writers.

Blues magazine, issue #1, edited in Auckland by Henry Jackson and David Colquhoun, March-April 1969

The blues mission extended to the airwaves in 1969 when Midge Marsden, now working for the NZBC, launched Blues Is News on 2ZB. With fellow musician and NZBC employee David Knowles, he presented a weekly serving of blues records. The show leaned heavily on white British and American blues – Mayall, Paul Butterfield and their ilk – until Marsden received a communication from listeners Rick Bryant and Bill Lake, suggesting he focus more on the music’s black originators. “I got this really nice a very polite letter. It said, ‘Dear Midge, wonderful programme you’re doing here, but there’s a few things you need to know...’ They put me on the right track, giving me the gospel according to St. John Lee Hooker. Turned me on to the real thing.”

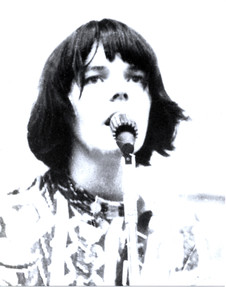

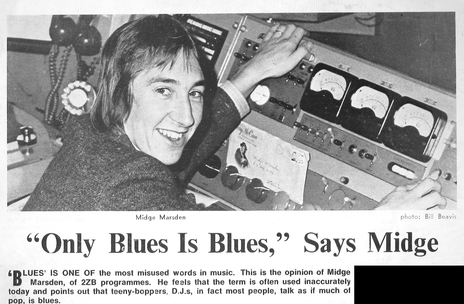

"Only blues is blues," says Midge, early 1970s

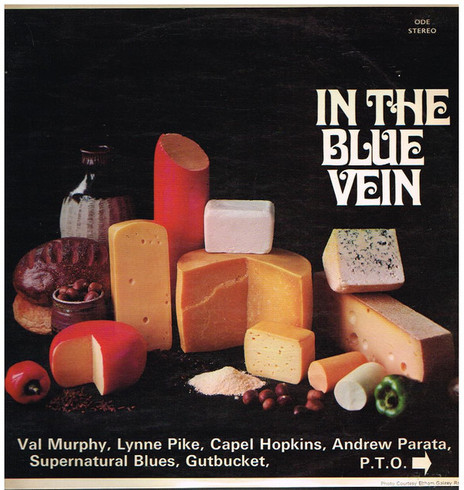

Between the late 60s and early 70s, blues reached critical mass, with blues clubs blooming in Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, Dunedin – even Hawera. An aural snapshot of the Wellington scene can be found in the 1969 album In The Blue Vein, produced by local record retailer and blues enthusiast Colin Morris, with liner notes by Midge Marsden, and featuring tracks by Val Murphy, The Capel Hopkins Blues Dredge, Gutbucket, and The Supernatural Blues Band, among others.

In the Blue Vein - a compilation of late 1960s Wellington blues acts, released on Ode in 1969

New Zealand finally began to see many of the international blues legends in the flesh. Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Muddy Waters, B.B. King and Willie Dixon all toured in the early 70s, while John Mayall paid several visits, sometimes bringing significant black musicians in his line-up, such as the Texan guitarist Freddie Robinson. These concerts would reliably fill town halls, opera houses and student union halls in the main centres. But promoter Barry Coburn may have been overestimating the pulling power of the blues when he booked Western Springs Stadium for a one-day international blues festival in March 1975. The lineup was for connoisseurs: Hound Dog Taylor, Freddie King, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, plus English bluesmen Alexis Korner and Duster Bennett. But there were other factors the meant the turnout was disappointing. Don ‘American Pie’ McLean was playing in the city, and the weather was poor. Coburn lost money.

British bluesman Duster Bennett and Barry Coburn as the Western Springs Blues Concert was about to start in 1975 - Photo by Murray Cammick

Curiously, just as New Zealanders were finally getting to hear some of their blues heroes up close, the “blues boom” seemed to be ending and the first wave of local blues groups began to dissipate. Alastair Riddell (of The Original Sun) turned towards prog-rock with his next group Orb, and Killing Floor’s Henry Jackson formed a group inspired by the music of Frank Zappa. Bill Lake and Rick Bryant – while maintaining a vehicle for pre-war blues in the Windy City Strugglers – headed towards funk and art-rock with Mammal. Even Midge Marsden briefly forsook blues for country rock, leading the popular bar band Country Flyers.

By the end of the decade, Midge had reaffirmed his vows to the blues, and after a spell in Australia fronting the heavily blues-based Phil Manning Band he returned to lead a series of blues-dominated outfits of his own.

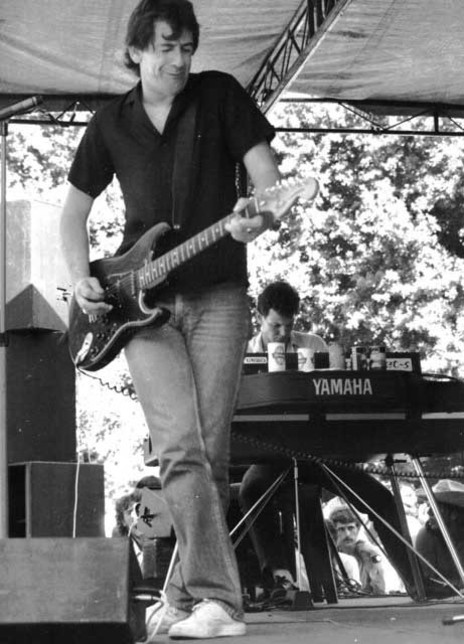

An important figure to emerge in the mid-70s was the Lancashire-born Hammond Gamble, whose group Street Talk were a major fixture on the Auckland pub scene for the latter half of the decade. Though Street Talk was never exclusively a blues band, Hammond brought a bluesy delivery to everything he sang, combined with a guitar style that showed a long and deep immersion in the playing of Clapton, Green and their black antecedents.

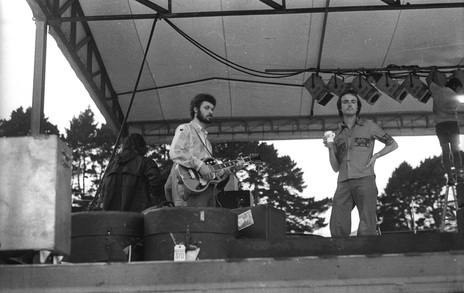

Hammond Gamble with Street Talk at Albert Park, 1975. Stuart Pearce is behind.

The 1980s arrived and a new generation of local blues bands began to appear. The predominantly 12-bar music, by now widely familiar, became a kind of shorthand for boozy good times. Blues bands proved a good fit with the large number of pubs and taverns now hosting live music, in both the major centres and the provinces.

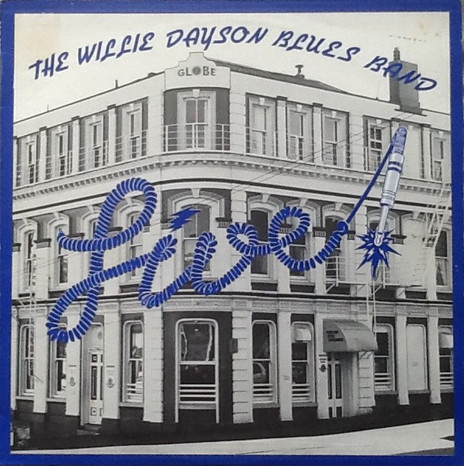

The Willie Dayson Blues Band's 1981 LP, Live at the Globe

In Auckland The Willie Dayson Blues Band formed around guitarist Dayson and harmonica player Brian Glamuzina. Their rock-infused blues proved a crowd-pleaser in pubs up and down the country. A typical set is captured on their 1981 album Live At The Globe, recorded at one of their favourite Auckland haunts. In Wellington, a similarly bar-friendly variety of blues was served by The Mangaweka Viaduct Blues Band, featuring the guitar pyrotechnics of Dougal Spier.

The Backdoor Blues Band took the blues to more histrionic levels. Originally from Dunedin, they began as the busking duo of harmonica player/vocalist Ted Clarke and guitarist Ainsley Day, but grew into a seven-piece travelling showband, complete with horn section and leopard-skin jackets, and became one of the country’s biggest-drawing pub acts. Their performances would climax with the manically energetic Clarke climbing on top of the speaker columns, interspersing harmonica solos with fire-eating displays and full-body gymnastics.

From the Hutt Valley came the Dick Thrust Blues Band, fronted by Nick “Tich” Rowney, whose approach to the blues was hardly any more sophisticated than their name, and Chicago Smoke Shop, which launched the career of Darren Watson, one of New Zealand’s most enduring blues players. Watson was barely out of his teens when he formed Chicago Smoke Shop in the early 80s, with harmonica player Terry Casey and drummer Richard Te One. Influenced by contemporary American blues bands like The Fabulous Thunderbirds and Roomful Of Blues, Smoke Shop combined high-level musicianship with a sharp stage presence. Since the group disbanded in the early 90s, Watson has maintained a profile as a solo artist (though usually backed by a band) and developed as a writer of original songs that are steeped in – but not beholden to – the blues. A sideshow of the 2014 general election was the Electoral Commission’s decision to ban from broadcast or sale his song ‘Planet Key’, unless it was labelled as an election advertisement. Watson, who wrote the funky blues as a piece of satire, fought against the ban on the basis of freedom of expression, finally winning his case two years later.

Through the 80s, Wellington-based Dave Murphy and Marg Layton maintained the link between blues and folk, taking their acoustic blues – both individually and as a duo – to folk clubs and festivals as well as pubs around the country. Bullfrog Rata started out in the late 80s, busking his blues around the towns of the Manawatu. He went on to play with Midge Marsden, and sometimes teams up with fellow acoustic blues troubadour, Shayn “Hurricane” Wills.

The Southern Blues Club, formed in Christchurch in 1984 by a group of local enthusiasts, and ran a series of bars devoted to live blues – most notably the Southern Blues Bar, which ran from the late 80s until the earthquake of 2010. The Hamilton Blues Society was formed in 1995 by British expat and Bay of Plenty guitar-slinger Mike Garner, has organised festivals and concerts and continues to host a monthly jam night, while in Wellington, Capital Blues Inc – formed by Dougal Speir and fellow Wellington blues player Pip Payne – has hosted the weekly Roomfulla Blues night every Thursday since 1996.

In the 90s, the Blues, Brews & BBQs franchise capitalised on the popular association between the blues and alcohol with outdoor festivals around the country, while locally-based blues clubs continued to sprout in the regions.

Jan Preston - Jan Preston collection

British-born, Tauranga-based guitarist and singer Derek Jacombs formed Kokomo in 1991, initially playing pre-war Delta and ragtime material with focus on guitar and harmonica, gradually becoming a vehicle for Jacombs’ original songs, with full rhythm section and horns.

Local blues performers continue to emerge in the new century. Auckland guitarist Tom Rodwell, who often performs in tandem with his partner Coco Davis, has developed a unique but decidedly bluesy style, incorporating rhythms from the Caribbean and ring-shouts from the Georgia Sea Islands.

And the old ones keep on going. In the late 80s, Rick Bryant and Bill Lake, after long spells in various rock and R&B bands, resurrected the Windy City Strugglers, blues remaining the foundation if no longer the sole ingredient of their music. In 2005 they toured France and Britain, appearing at blues clubs and festivals.

The Windy City Strugglers, 1995 - Bill Lake, Andrew Delahunty, Rick Bryant, Nick Bollinger, Geoff Rashbrooke

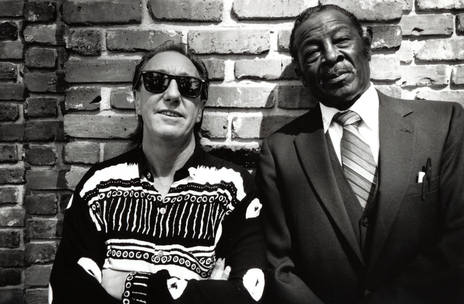

Midge Marsden has also performed extensively overseas, touring in Australia, Britain and the USA, and for a time took up residency in Mississippi. After meeting and performing with the veteran harmonica player Willie Foster in Mississippi, Marsden brought Foster to New Zealand in the early 90s, where he toured as a guest with Marsden’s band.

Midge Marsden and Mississippi Willie Foster, 1991

In 2009 Darren Watson won the blues category of the International Songwriting Competition. Blues and boogie-woogie piano specialist Jan Preston, who now bases herself in Sydney, regular appears at festivals around the world. When Brownie McGhee toured here in the early 1990s, several years after the death of his long-time sidekick Sonny Terry, he chose local guitar and harmonica player Neil Finlay to accompany him.

For the most part, though, New Zealand’s blues performers adhere to the music’s blue-collar ethos, playing in bars more often than concert halls; more journeymen-and-women than superstars. On the upside, the genre they have chosen is an enduring one that has outlasted fads and fashions, and ensured long careers for its practitioners.