Parkes’s childhood was spent in Spreydon, Christchurch, playing sports and hanging out with friends. His musical journey started traditionally – classical piano lessons, with a stereotypically scary piano teacher. At 10 he changed teachers, swapping to local jazz drummer Harry Voice for a year of modern piano, and arranging lessons. A subsequent music teacher taught popular hits of the day, including Rod Stewart’s classic, ‘Sailing’, which he played on the piano during assembly at Manning Intermediate. The experience was “scary, but fun!”

His tenure at Christchurch Boys High School was a mixed bag musically – he calls it “horrible” – though other pupils in his brother’s year played in bands such as Ballon d’Essai, and The Berts. “That was pretty inspiring.” He discovered the joy of record buying, collecting “XTC, Split Enz, everything I could on Flying Nun – especially The Pin Group, The Clean, Builders, Gordons, No Tag – [and] any independent 7-inch single I could afford.” Music became central. “I would go into town several times a week for work or to look for records or free magazines. Staying up late to watch Radio With Pictures, tuning into Radio U … I was obsessed!”

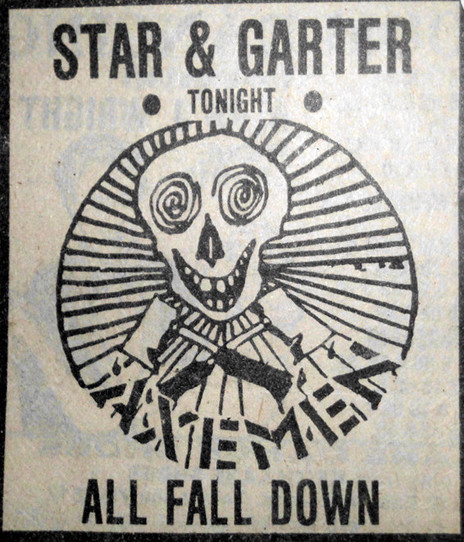

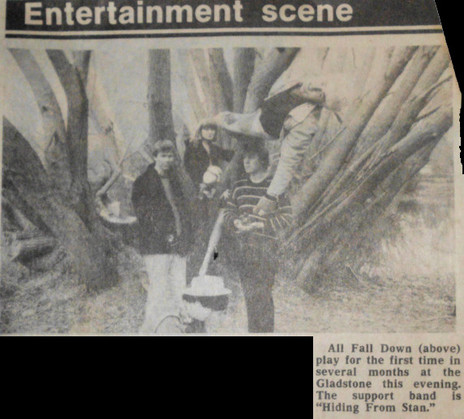

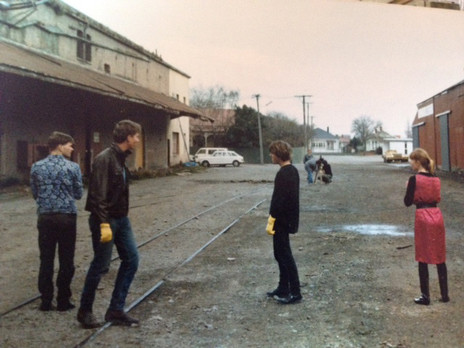

In 1985 ALL FALL DOWN played its first orientation gig.

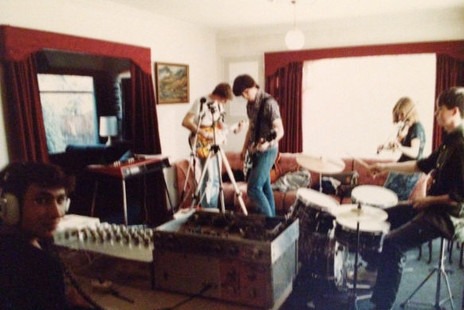

It all started to fall into place after an uncle gave him a guitar (named “wee boy”). He wrote his first song in fourth form, began buying instruments a year later, and started jamming with Campbell Taylor’s band The Bare Essentials. Initially Parkes played keyboards before moving to guitar. Their first “gig” was to friends in a garage during the school holidays. “It was quite fast punky stuff, very much influenced by The Clean and Joy Division,” he says. After playing in more garages, and undergoing line-up changes, they started playing pubs in 1984, supporting bands such as the Axemen, Netherworld Dancing Toys, The Bats, and Scorched Earth Policy. They changed their name to All Fall Down, taken from the television show The Bawdy Adventures of Dick Turpin. With Esther McNaughton joining on vocals and violin, the line-up seemed complete.

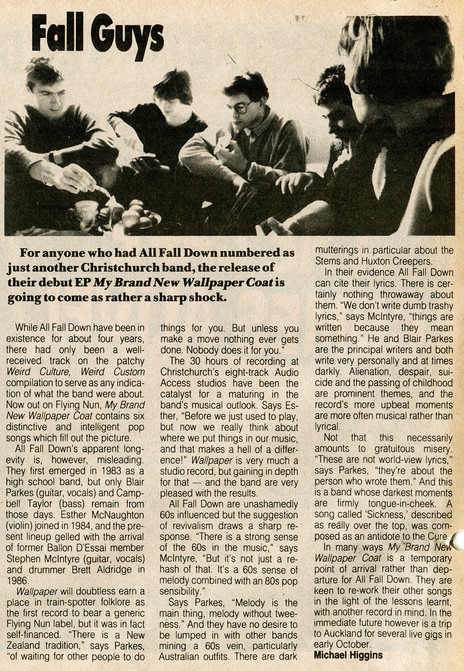

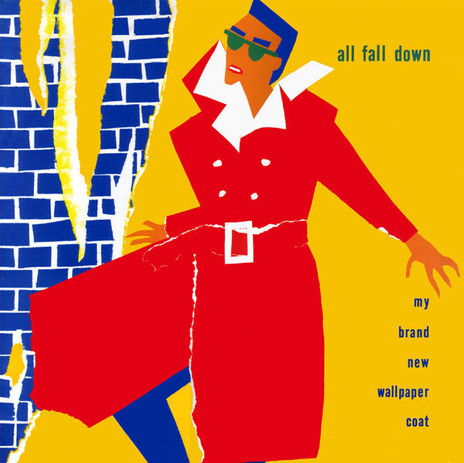

In 1985 All Fall Down played its first orientation gig – 10 more would follow – and began recording demos for a tentative release on Flying Nun. Parkes started experimenting with recording his songs onto cassette, eventually purchasing a Fostex Portastudio for $799. Further line-up changes saw Bert Aldridge and Ballon d’Essai’s Stephen MacIntyre joining Parkes, Taylor, and McNaughton, and this line-up went into Audio Access Studios. On the resulting EP, My Brand New Wallpaper Coat (Flying Nun, 1987), Parkes and MacIntyre’s jangly guitar music reflects much of the early Flying Nun sound.

A video was made for ‘Black Grattan’, however things were shifting, as Parkes recalled online: “Our friendships had ground away. Lives were changing, and sometimes things were a little tense.” At the end of 1987, All Fall Down was over, but new doors were opening for Parkes.

One of them was The Letter 5. Parkes met Richard James in Auckland in 1987, and over the next 18 months they developed a musical rapport. Parkes wrote the song ‘Good Place’ at James’s house, and flew to Auckland to record it with James and Andy Moore. He began travelling there frequently and experienced the Auckland music scene, but decided against moving north, partly for financial reasons. The Letter 5’s upbeat EP Now You Are Here (Flying Nun, 1992) stepped away from the label’s renowned jangle-pop, incorporating folky textures. Its release was delayed due to changes in Flying Nun’s ownership.

Another reason Parkes didn’t move to Auckland permanently for The Letter 5 was his increasing involvement with Swim Everything, a band with Campbell Taylor and Damian Zelas. It was a fun group, he says: “hard, loud music, drum machines and two distortions on your guitar”. Zelas’s interest in electronics and technical aspects of music and recording led the band into what Parkes calls a more “contemporary” approach to music making; it was a conscious shift away from the classic 60s pop structures he had previously used. Initially called F.K.E., they made a self-titled cassette EP in 1988 (again featuring artwork by Parkes), with a video for melodic noise-pop single ‘Bolton’. Further recordings followed in the early 1990s: another self-titled and self-released cassette-only album in 1990, and ‘Clarity’ – a song released on 7" lathe-cut disc under the name Geraldine in 1993, two years after they called it a day.

At the start of 1988, Parkes also regrouped with Campbell Taylor and All Fall Down drummer Brett Lupton to form Little Dead Things with John Chrisstoffels, Mark Tyler and Francis Hunt. The group performed largely around Christchurch, with a gig at The Pitz nightclub in Dunedin being especially memorable. Parkes recalled in his blog, “The venue was well named – a skinhead-run room in a freezing, damp cellar … there was a near-fight with an enormous drunk, angry skinhead and his friends. We gave up on trying to play and managed to quietly pack up and slip out the door.” Little Dead Things’ self-titled mini-album of guitar-based alt-rock was released in 1991 on Failsafe Records, before the band went its separate ways. During this time Parkes recorded Black Light – his now hard-to-find first solo album – on cassette.

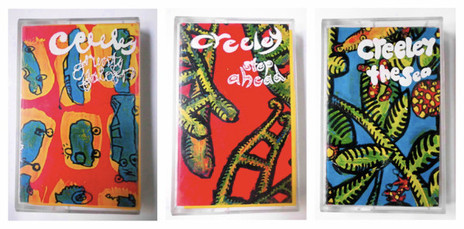

A new band called Creeley developed out of a burgeoning friendship with John Kelcher.

As the 1990s began, a new band called Creeley developed out of a burgeoning friendship with John Kelcher (Sneaky Feelings). The pair met during the final days of All Fall Down, and initially collaborated on music for Sonlite, Campbell Taylor’s local production about the invention of a sun machine.

With the addition of Bert Aldridge on drums, and later Dean Aldridge on bass, Creeley eventually released three cassette EPs on the ahM label: Grunty Falcon, Step Ahead, and The Sea. Parkes is clearly proud of Creeley, telling New Zealand Musician magazine the band challenged him – “the other players were really good” – but there was also disillusionment. “You work really hard, and you think you’ve done quite good work, and nobody really cares.” Parkes thinks their best material is unreleased. “We were a lot more creative in the practice room and in our final couple of years,” he says. Failsafe Records supported the band, but called their sound “a little out of sync with that of the current scene in Christchurch.”

Before the end of Creeley, Parkes started Range, a trio with Hayden Sharp and Bert Aldridge. Originally intended as an outlet to record songs that didn’t suit Creeley, Range began as a request to play country music. After 1997, when Sharp moved overseas, it was primarily a recording group. Parkes liked the collaborative aspect: “It’s some of the stuff I’m most proud of.” In 1997 Wrong Records compilation Dollar Mixture included ‘Nothing’, a favourite of Parkes. Two years later Range’s first album arrived. All the Way to Lunch, a 20-song collection of guitar-based alt-rock, was a b-Net finalist. Range is a continuing project: Henry Rivers, a mellower album of beautifully crafted material emerged in 2014, and a follow-up EP, Shed Range, was self-released. The trio is especially important for Parkes in terms of writing and performance; Henry Rivers “felt like we’d lifted our game”.

As the 2000s began, Parkes had fingers in multiple musical pies. With Richard James and Marcus Thomas he formed 103, named after the band members’ combined ages. The group unexpectedly took Parkes away from the guitar. “It was a lovely singing band … that was the end of me and guitars for quite a long time!” Their album Coaster was released on Seaside in 2003.

Meanwhile Parkes was quietly working away on another solo release, The End. Recorded on a Tascam 4-track cassette recorder, The End has some intricately arranged and composed songs (eg ‘19 Moments’) among the lo-fi production and often experimental textures. The following year, Parkes found himself again in Wellington with Zelas, recording East Coast, a light and airy collection of acoustic pop songs, the last under his name for 15 years.

After 103 ended, Parkes and Thomas continued writing together, forming their duo Thomas:Parkes to explore electronica using keyboards and a synthesiser. They promoted their synth-electronica album Big Machine with live gigs at The Wunderbar and Creation venues; the duo sometimes felt trepidation as they often couldn’t hear the backing tracks which incorporated many of the parts. Chosen as the South Island support act for The Phoenix Foundation’s 2005 Pegasus tour, Thomas:Parkes’s star was on the ascendant. Further gigs followed before beginning to collaborate with vocalist Helen Greenfield from Barnard’s Star. “It sounded really, really good having that extra voice, so we decided [to] ask Helen to join the group,” says Parkes. Now a trio called The L.E.D.s, they quickly put out the album We are the L.E.D.s. in 2006. Unfortunately, their previous label, South Recordings was dissolving: a situation Parkes describes as a “pretty shitty experience!”

The L.E.D.s’ debut album of melodic electropop was a slow-burner, accelerating 10 months after its release when Russell Brown featured it on his Public Address blog. The reviews were positive, Real Groove magazine calling it “a finely executed work”. There was a huge amount of interest in the band, and they played throughout New Zealand extensively, with their songs featured on TV shows including Outrageous Fortune and Go Girls. While a good time was had, it coincided with both Parkes and Thomas having young children, so sleep was in short supply. “I’d play a gig that night, but not until one in the morning. You’d play till two, pack down by three, get home at four, not sleep, and be up at six. It was really, great fun, but would take me a week to recover!” The L.E.D.s. were a great performance outlet. “We just used to have absolutely fantastic gigs … it was a very challenging group to be in, in a sense of just technically pulling it off every time.”

Again showing a restless side, in 2009 Parkes had a minor revolt against electronica, creating a short-lived duo, Bridle Path, with banjo player David Haywood. Their musical philosophy was to eschew electronic instruments and effects, and their subsequent four-track EP The Monteith’s Sessions was bluegrass. Adding to his projects, Parkes wrote 100 Things You Might Use When Songwriting and Recording, a booklet of suggestions for creating music.

The 2011 Canterbury earthquake, unsurprisingly, halted any plans for live performances.

Parkes says The L.E.D.s. experience was “incredibly satisfying artistically, doing something new and exciting.” But it came to an end after one EP (the poppier Goodbye to the Light) and four albums of electronica (We Are the L.E.D.s, Still, Glass Comforts,and Dunes). “It was … music with quite a lot of constraints!” he says. “I needed to do something else.”

Fate stepped in on 22 February 2011: the Canterbury earthquake, unsurprisingly, halted any plans for live performances. “The earthquake got in everyone’s way, really … if you’ve got to work really hard on getting your house fixed, then that’s … a greater priority.” In the end, The L.E.D.s retreated quietly; Dunes was released digitally in 2012. Parkes, however, was already looking to projects without any constraints of conventional songwriting.

One such outlet was Chimney Book, a time-based diary-cum-experimental film made for the Public Address Orcon Great Blend event, and Parkes’s personal response to the earthquakes. Created over a month, it is evocative and powerful, examining images and journal entries that chart life during the earthquakes’ aftermath. Phrases, and keywords – dust, memory, and place – form markers in the narrative, and the navigation through his damaged city and home was a response to what he termed online “the shifting emotional and physical landscape”. He also created the soundtrack: a collage of spoken words, music and everyday noise to accompany his and his family’s experiences during that time.

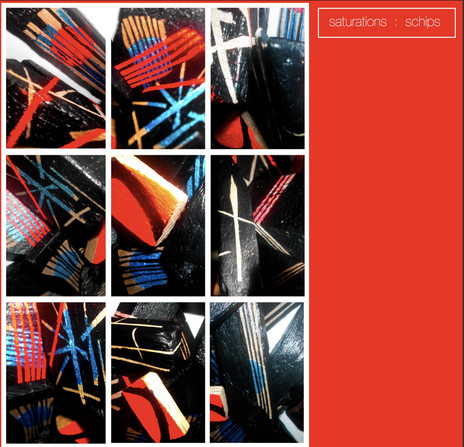

Parkes’s next move – a solo experimental project called Saturations – he describes as a freeing experience. “I could do really loud, unsubtle things,” he says. “I just needed to blow off some steam!” … Saturations is all about how can I much make something that’s still acceptable to listen to, but still have the biggest delay possible, or the nastiest sound.” Coming after the earthquakes, the process and outcome were cathartic; the single ‘Kittens’ was a burst of electro-rock energy. “It’s more like seeking fun … everything in life at that point was extremely difficult … I was being absurdly positive.”

The five Saturations releases are a stylistic mix. Experimental, pop, rock, and electronica tracks all share space together, and document Parkes cutting loose from the restrictions of writing or performing in an expected way. There’s a sense of glee and freedom, with infectious pop hiding beneath an experimental layer.

In 2013, he started a more experimental sound-art project, Condensations, which examined the effect of his audio and physical environments. He began with field recordings that observed space and time, and the 2016 Condensations release Flies, Rain, Thunder, Cats took this further, using the sounds to find a more urban soundtrack.

In 2016, Parkes released the digital solo album Cardigan Bay, again on the Seaside label. The album was written after Parkes picked up a guitar that his uncle gave to his son, but was too big for him. “I’d really avoided songwriting on an acoustic guitar,” he says. After writing 10 songs he wasn’t enthused about, one called ‘Yours and Mine’ emerged. “That felt a bit new to me in terms of songwriting, and I got quite excited … when you write a lot of music, you realise not every one is a gem,” he says, laughing.

The themes of Cardigan Bay are a mix of life, death, and imaginary situations, and ‘Stormy Seas’, ‘Yours and Mine’ and ‘Shoulders’ stand out for Parkes as they reflect his original vision. ‘Stormy Seas’ in particular is radio-friendly, something he wanted. “I wanted it to be something you put on and enjoy listening to.” Cardigan Bay, he says, is stylistically “a very small strand of the music I do, and not really the stuff that pushes me artistically ... It wasn’t really the direction I was, or am going, in.”

Saturations came in 2017, under his own name. Parkes began the album “as a reaction to the challenges of some of the things I had been doing … I allowed myself a lot of the same freedoms with the treatment of the songs.” The year before, after a lengthy break from live performance, Parkes had started gigging again, with his band Blair Parkes and Cardigan Bay (Luke Sole, Ben Baird, and Ryan Chin). Sole had suggested to Parkes they form a band to play his new material.

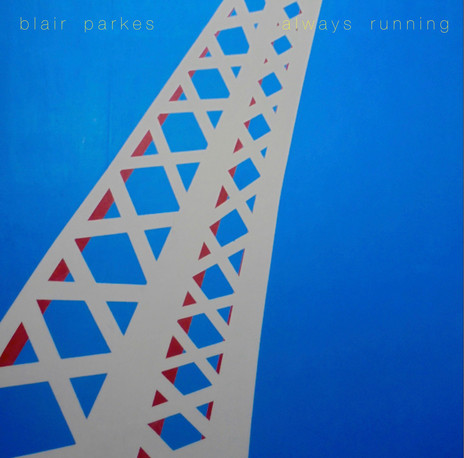

Parkes continues to work on new material in his shed, releasing the album Always Running on Seaside in July 2018. ‘Heavy Lifting’ – a “fuzzed out” song from it – hit a nerve almost immediately, charting as RDU’s single of the week, and receiving plaudits from the websites of Flying Out and Under the Radar.

With drums by Ryan Chin, and backing vocals from Miss Mercury (Helen Greenfield), ‘Heavy Lifting’ fuses alt rock and shoegaze, with some vintage vocal stylings thrown in. Always Running is a collection of synth-based, snappy songs which often juxtapose darkness with a lighter sonic touch. It marks a return to a harder, heavier sound, which wasn’t a conscious decision, “more a way of grouping songs together that worked … more cohesion in tempos and vibe.”

Little Rapids, Parkes’s second album for 2018, also features Chin on drums. Its acoustic-guitar based pop songs are strong in melody and beautifully crafted – a constant in Parkes’s work. ‘Little Rapids’ and ‘Dig for Water’ in particular appeal – the former a lovely dark track that sonically harks back to Parkes’s days in Creeley, while the latter has a hypnotic, flowing, vibe. The difference between the two albums is clear: Almost Running is “quite a forward-leaning set of songs … definitely more in your face, while Little Rapids is more pastoral and contemplative, perhaps.”

When Parkes looks back, many things stand out: playing live at The Gladstone with All Fall Down at age 17; times with Creeley in the bandroom, jamming and finding those transcendent moments; his refining of a deliberate and uncluttered aesthetic on the first L.E.D.s. album.

He remains “incredibly grateful” to the help he has had from friends and family, who have lent gear, advice, time and support. Without them, he’s adamant “none of this would have been possible”.

Parkes’s artistic output goes beyond music; he works in other media including the written word, photography and painting. However he keeps returning to music because, he says with a laugh, “as fun as it is, I try a bit harder ... It’s what I do.”