Grindlay became New Zealand’s most prominent jingle writer and a film composer; Hewson joined Dragon in Australia and led them to huge commercial success, and Hunter released three lauded country music albums.

Rayner went on to Split Enz and session work, McKelvie stamped his signature on the Australian classic ‘Girls On The Avenue’ and countless releases at home, Dunningham joined Mi-Sex via Coup D’Etat, and Woolright became Dave McArtney’s right-hand man in The Pink Flamingos, rejoining him in latter-day Hello Sailor.

Over their four-year existence, Cruise Lane released three ineffectual singles, but their most compelling recordings never saw the light of day – a series of Paul Hewson-penned demos that join the dots between his teen band The Arch’s ‘Sit By Your Window’ and his first recorded Dragon composition ‘Show Danny Across The Water’.

The original Cruise Lane came together in early 1971 after a conversation between the Embers nightclub owner Nick Villard and bass guitarist Jerry Biggs in which Villard mentioned he was looking for a new resident band. Biggs had played in a number of groups – though, by his own admission, “nothing worth talking about” – and promised to get him one.

Villard, a folk singer who had released singles on Pye in his native England, arrived in Auckland in the mid-1960s and made a name for himself in the cabaret scene and on television before setting up the Embers and “encouraging artists to create original sounds”, as he told the Central Suburbs Leader in 1968.

Naming themselves Cruise Lane after a street bordering the Embers, they started the next weekend.

Between bands, Biggs hit his contact book and pulled together a line-up of musicians he knew or who were recommended by friends. He was on bass, with former Killing Floor frontman Al Hunter on vocals, Tony Pilcher on guitar, Claude Radics on drums and Paul Lee on tenor saxophone.

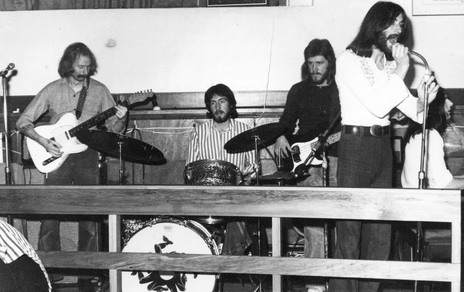

The nameless outfit learned about nine songs, rehearsed like crazy and successfully auditioned for Villard. Naming themselves Cruise Lane after a street bordering the Embers, they started the next weekend, Lee adding the house grand piano and Hammond organ to his arsenal.

“So we had to start with nine songs,” Hunter said. “Every set we’d play them again and again and again. But we soon got a repertoire. We were rehearsing every day. It was great. It was what we’d dreamed of – to have that residency, six nights a week.”

That repertoire of the latest Leon Russell, Van Morrison and Allman Brothers Band releases came from the combined record collections of Hunter, his teenaged nephew Roger Liddle and Hunter’s good friend and Pye employee Rhys Walker, whom the band asked to be their manager.

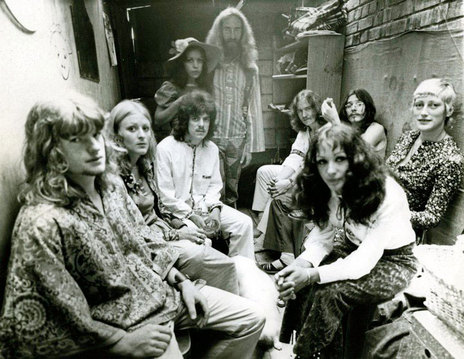

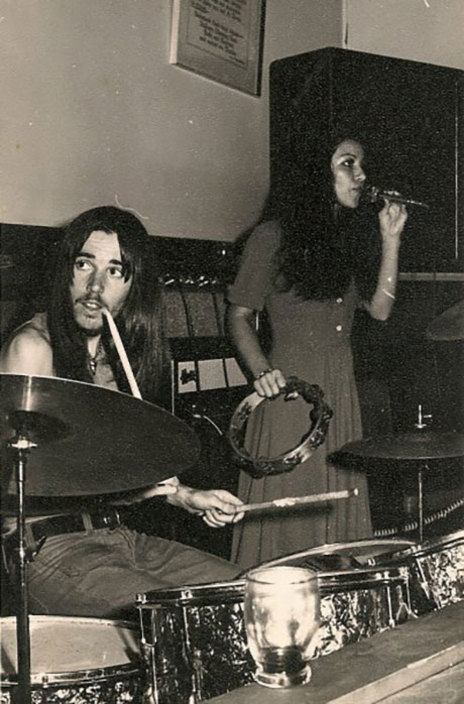

The Embers attracted a lot of musicians who would inevitably get up to jam. At least once a week, Villard would be enticed from the leopard skin lounger in his nautical-themed boudoir office for a set. “Follow me, boys,” he’d intone.

“Villard was just such a great personality,” Hunter said. “He had this little recording booth and he’d quite often record what was going on. If there were a jam session, he’d record it. He had an immense library of reel-to-reel tapes.

“He was a pretty hard taskmaster. He told us, ‘Every night, no matter if there’s one person in the audience, you play like you’re at Madison Square Garden.’ It was a great apprenticeship.”

Other acts would come in for occasional spots, including the folky Tole Puddle and an acoustic duo consisting of former Underdog Murray Grindlay and one-time guitarist with The Action, Mike Wilson.

Months earlier, Grindlay and Wilson had put their own band together for a gig at the Embers but Nick Villard didn’t like them. When they began working as a duo for him, Villard exclaimed, “Oh, I didn’t know you could actually sing, Murray.”

Following a stint in Canada with all-female pop group Fair Sect, singer Kaye Wolfgramm – an acquaintance of Biggs – arrived back in Auckland. After chiming in so sweetly at rehearsal, she was swiftly brought into Cruise Lane.

Not long after, Biggs was sacked in favour of Hunter’s wife’s brother Peter Kershaw. “My demise was sort of political,” Biggs recalled. “Al had a brother-in-law who was a good bassist, so he worked it so that I was pushed, voted out in favour of him. They said that I wasn't a good enough bassist. Shit happens.”

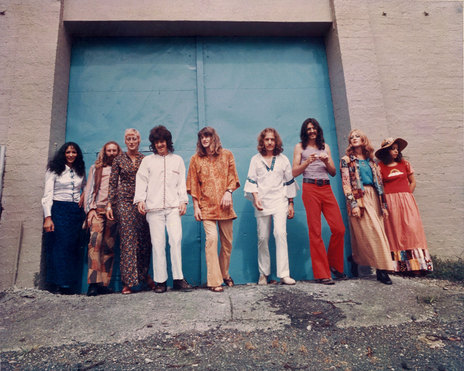

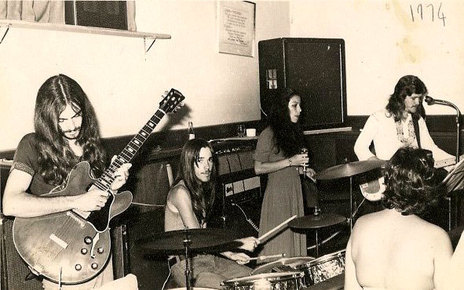

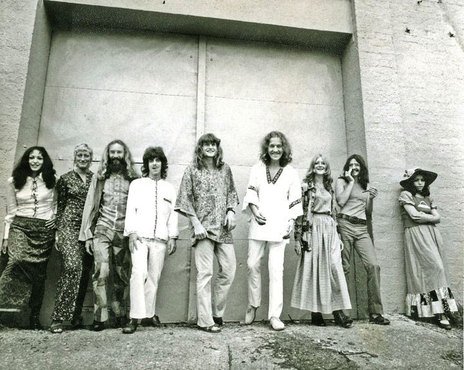

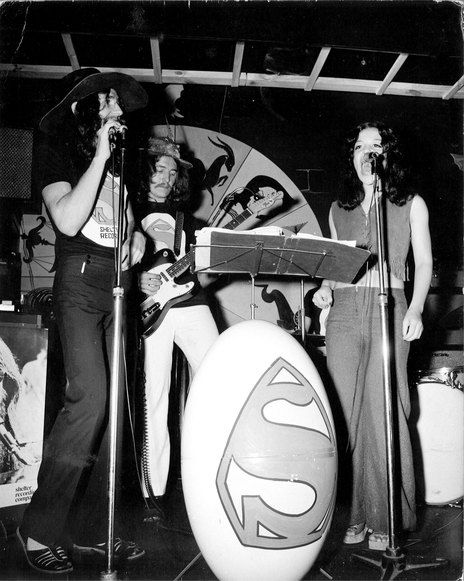

When Cruise Lane were selected as support for Daddy Cool at Carlaw Park, Auckland in late 1971, they went the whole Delaney & Bonnie, Joe Cocker, Mad Dogs & Englishmen route, bringing in Bob Smith on Hammond organ to enable Paul Lee to concentrate on saxophone and even going as far as adding a backing choir which included Josie Rika, Hunter’s first wife Shirley and a waitress named Pauline.

The expanded Cruise Lane blew Daddy Cool off the stage and prompted their Sparmac management team to suggest a move to Melbourne to record an album.

The expanded Cruise Lane blew Daddy Cool off the stage and prompted their Sparmac management team to suggest a move to Melbourne to record an album. Early in the new year, they repeated the feat while opening for Mungo Jerry and Edison Lighthouse at Western Springs.

Punters who turned up at the Embers when one of those support gigs were looming would be lucky enough to see the band and backing choir in full flight. “We’d bring the choir in and we’d all clamber on the little stage and have an onstage rehearsal,” Hunter chuckled.

While planning the Melbourne move, Rhys Walker organised for Cruise Lane’s debut single to be released on the Pye subsidiary Family label in 1972. Although credited to Kaye Wolfgramm And Cruise Lane, the A-side didn’t even feature the band.

Berklee College of Music graduate and jazz musician Tony Baker was looking to build his profile as a songwriter and producer and needed a female voice for his song ‘Death Is In The Air’, hiring Wolfgramm to sing to pre-recorded backing. The flip side was the band with Hunter on vocals on the Paul Lee-written ‘Ego’.

They put down three other songs during the Stebbing session – including Delaney & Bonnie’s ‘Where There’s A Will There’s A Way’ and ‘It’s Hard To Say Goodbye’ – but Pye decided to go with ‘Ego’ as it was an original number.

When Wolfgramm fell pregnant and opted out of the Melbourne trip, the Sparmac offer all but evaporated. “She was a major part of the band,” Hunter said. “She looked good and she sang good, you know, wonderful voice. They might have even got rid of me in the end!”

Paul Lee and Tony Pilcher refused to go without Wolfgramm, but Hunter, Peter Kershaw, Claude Radics and manager Rhys Walker (who was offered an A&R role with Sparmac) ventured to Melbourne to test the water. Former BLERTA organist Alan Moon soon followed.

“We couldn’t get anything happening,” Hunter said. “We didn’t have any contacts. We went over there thinking we’d be able to find players, but we couldn’t find players and we couldn’t find a gig.” To add to the stress, Hunter’s wife was heavily pregnant in Auckland and their dog had died when he was run over by a car.

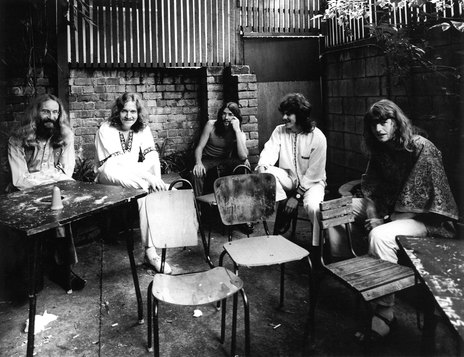

Back at the Embers, Lee and Pilcher hit upon a quick solution to keep Cruise Lane working and amalgamated Murray Grindlay and Mike Wilson – still playing as a duo at the club – into the band, Wilson moving to bass. Drummer Bruno Berens (who later played with Papa) was also recruited and Wolfgramm and Josie Rika performed regular guest spots.

With Grindlay and Wilson in partnership writing jingles, their involvement added to the band’s songwriting stock. Until then Lee had been the only writer, but with Villard insisting on more original songs, Lee and Grindlay began introducing their own material.

Meanwhile, Hunter and Radics returned from Melbourne after a month or two to find Cruise Lane had moved on. Walker came back about six months later, only Kershaw stayed. “Basically, until we got back we didn’t realise that they’d carried on,” Hunter said.

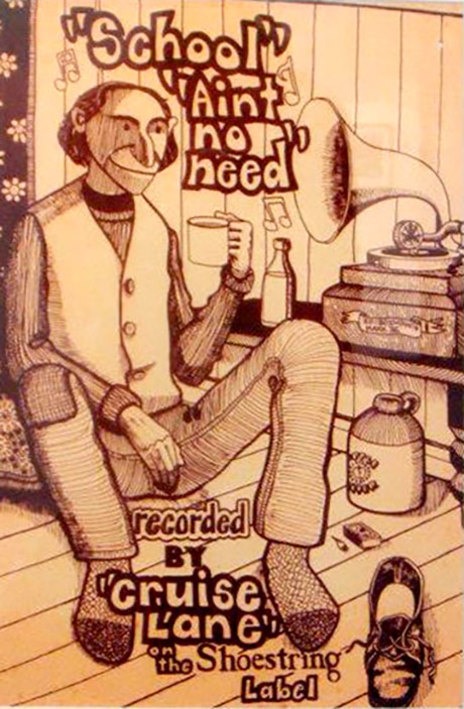

Early in 1973 came the second Cruise Lane single – Lee’s ‘School’ b/w Grindlay’s ‘Ain’t No Need’ – on Pye subsidiary Shoestring Records, but when the Embers closed, Cruise Lane moved to the Tabla three nights a week, where they had to drop most of their own stuff for a commercial repertoire.

Tony Pilcher left after a car accident and, following a spell of temporary guitarists including George Barris and Chaz Burke-Kennedy, Mike Wilson moved to guitar and Paul Woolright joined on bass.

“I can't remember the circumstances that got me into the band, only Murray and I had become good friends and I used to turn up at his flat in Parnell on a Friday night with a bottle of Jack Daniels and fish and chips,” Woolright said. “Maybe I bought myself in.

“Murray Grindlay and Mike Wilson were the first musicians I had worked with that subconsciously taught me how a rhythm section really worked. I learnt a lot from them after being in a totally free-playing band that Ticket were.”

Soon after moving to a residency at De Bretts Hotel in High Street, Cruise Lane folded.

Soon after moving to a residency at De Bretts Hotel in High Street, Cruise Lane folded. “It was a shithole of a venue,” Grindlay remembered. “We were playing two or three nights a week, making $39. We’d just come from the Embers where we were getting $100 each, a Hammond B3 on the stage, grand piano, beautiful recording gear.”

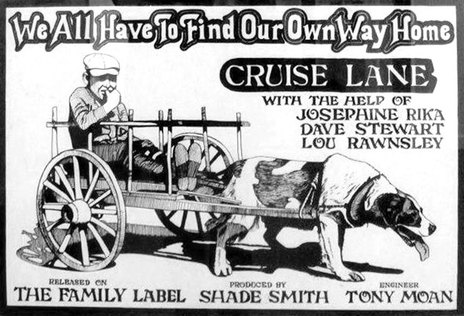

Grindlay and Wilson hung onto the name and even released Grindlay’s ‘We All Have To Find Our Own Way Home’ on Family as Cruise Lane with Lou Rawnsley, Josie Rika And Dave Stewart. The Rumour’s Shade Smith produced the single and the B-side was Rawnsley’s ‘Waiheke’.

The rest of Cruise Lane – Lee, Berens and Woolright – began rehearsing a soul repertoire with Josie Rika and guitarist Neil Edwards, another former Underdog, and were quickly picked up by Tommy Ferguson and renamed The Tommy Ferguson Goodtime Band.

In the audience for one of the final Cruise Lane gigs in June 1973 was guitarist Red McKelvie, fresh from several years in Australia as part of The Flying Circus and as a session man and recording artist in his own right. “Grindlay’s band was breaking up and we said, ‘How about we start a band?’” McKelvie said.

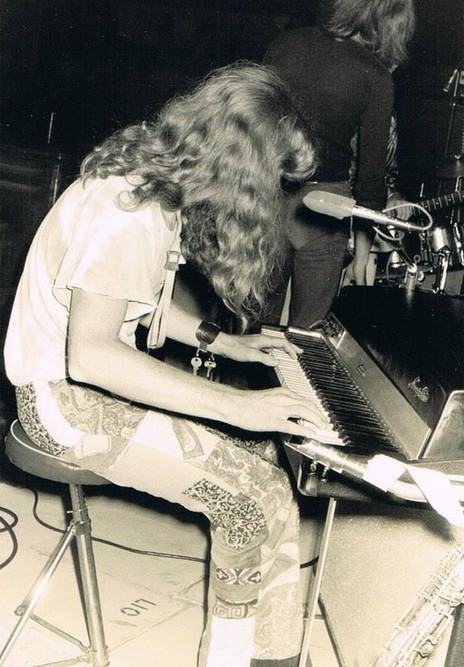

A little-known pianist who had been in an outfit called Freedom Express approached Wilson for a place in the new band. “Paul Hewson came to me begging for the job,” Wilson recalled. “He said, ‘I can play, man. I can really play.’ So we had a jam and he could play.”

“Me and Mike went around to his garret,” Grindlay continued. “My first impression was he would drink anything – he was throwing Cointreau back. He picked up some old Yamaha guitar and did a beautiful version of ‘Oxford Town’ by Bob Dylan.”

Hedging his bets by rehearsing with the new band and Ferguson’s band, drummer Bruno Berens took off with the Goodtime Band when they secured a spot on the breweries circuit. He was replaced by Brett Neilsen, formerly of The La De Da’s.

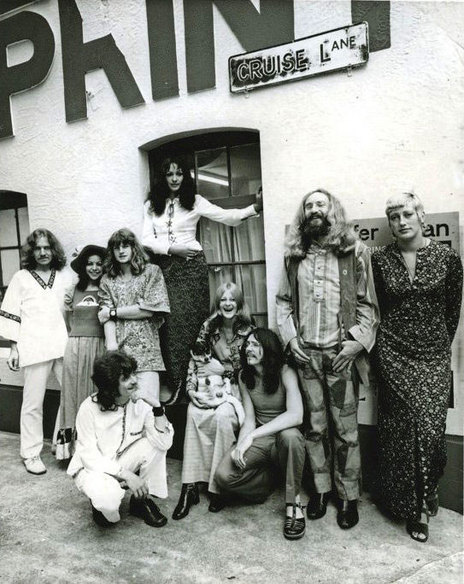

Bereft of any better ideas, the band christened themselves Cruise Lane and even got the De Bretts residency back.

Bereft of any better ideas, the band christened themselves Cruise Lane and even got the De Bretts residency back, augmenting their JJ Cale and Jerry Jeff Walker set lists with the Band-influenced songs of Paul Hewson.

“I’d just begun writing in 1972,” Grindlay recalled, “but when we started rehearsing his songs, I heard them and thought, ‘Wow, I’ve got a long way to go yet.’ They were sophisticated like The Band.”

“We tried rehearsing once at Paul’s pad in New North Road,” McKelvie said, “but the lady in the front flat called the landlord and he came around and gave Paul and us such a bollocking it was decided that we’d go out to Brett’s big, old villa in Kelston in the future. Which was brilliant until the lads really gave Brett’s wine cellar a real hammering one night!”

Planning to record a single, they went into Stebbings with producer (and former Invaders and Meteors member) Dave Russell to lay down demos, including Hewson’s ‘Just Like The Bible Said’ and ‘Life Has Just Begun’ and McKelvie’s ‘Anna Lee’.

Before the recording could be finished, the line-up blew apart on account of an awful assault after a gig at De Bretts. Upon refusing two drunken gang members “one more song”, the men came at Grindlay and Wilson, Wilson defending himself with the butt of his Fender Precision to one assailant’s face.

Eventually the bouncers intervened and shepherded the men away, but one of them hurled a shot glass at the stage, hitting Grindlay below the left eye. The incident was more than enough to have him give up gigging and also spelled the end of his jingles partnership with Mike Wilson when he decided to strike out on his own.

Hell-bent on staving off a day job, Wilson scrambled to keep the De Bretts gig but found McKelvie, Neilsen and Hewson reluctant. When he heard that the newly married Kaye Wolfgramm’s Kindred Spirit were finishing up at the Do Re Mi in Queen Street, Wilson nabbed her, her guitarist husband Steve Wilson and their drummer Paul Dunningham to complete a new-look Cruise Lane.

The inclusion of Kaye and Steve Wilson brought with it a new repertoire of Chaka Khan, Steely Dan, Earth, Wind & Fire, Rufus and Tower Of Power covers. It was definitely a dance band with Steve Wilson’s propensity for “heavy black funk”.

They quickly added pianist Tony Rayner, but he lasted just a few months before deciding to throw in his lot with arty originals band Split Enz.

They quickly added pianist Tony Rayner, but he lasted just a few months before deciding to throw in his lot with arty originals band Split Enz, changing his name to Eddie Rayner in the process. “Are you sure you know what you’re doing?” Mike Wilson asked him. “This is a pretty good gig.”

Having found nothing better, Paul Hewson was eventually coaxed back on piano and two weeks later had Dunningham ousted in favour of his old Freedom Express buddy Dennis Ryan.

One night saw Dragon guitarist Ray Goodwin swing by to catch up with Steve Wilson, his old mate from OK Dinghy days. Goodwin was impressed by Hewson’s piano playing and the pair swapped numbers.

This was the first version of Cruise Lane to occasionally venture outside of Auckland, including one trip to Waikato University where Mike Wilson and Hewson needled Ryan mercilessly all the way there for the sign taped to the back of the front seats in his immaculate Morris Oxford – “No eating or drinking in this vehicle.”

They also returned to Stebbings, demoing the Hewson songs ‘Goodnight Good Life’ and ‘Good Guys Never Die’. Despite Hewson exploring a more commercial vein, the demos failed to attract record company interest. Marc Hunter’s bombastic take on the latter song would appear on his 1981 LP Big City Talk.

A move to Gatsby’s in the Century Arcade three nights a week in early 1975 spelled the end for Paul Hewson. With baby number two on the way, he accepted a more lucrative offer from Jim Ford’s Dallas in South Auckland. Original member Paul Lee returned in his place but Cruise Lane’s days were numbered.

The demise of the band was recorded a few months later in Mike Wilson’s scrapbook. “After playing at Gatsby’s for several months and getting ripped off one more time I quit the band and got a day job,” he wrote.

“Steve and Kaye are in Brown Street, Dennis is with Billy Kristian in Hot Snuff, and Paul (Hewson) has, after a few months with The Dallas Four (sic), split to Oz to join Dragon.”

Inevitably any recollection of Cruise Lane begs the question, “Whatever happened to Kaye?”