AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

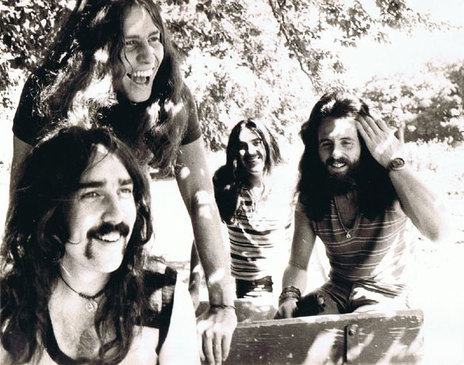

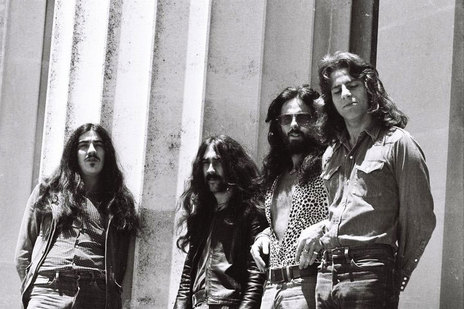

Ticket

But the four members of Ticket did not start out as psych-rockers. Paul Woolright grew up in the state housing suburb of Mt. Roskill, Auckland. As a boy he took piano lessons, but was more interested in plucking tunes on a neighbour’s acoustic guitar. By 1965 Beatlemania had struck, he had finished school and been kicked out of home for refusing to cut his hair.

He found a flat with a couple of musical pals and began teaching himself bass. His first instrument came from a books and bric-a-brac shop in Dominion Road, run by the mother of a friend, Graham Brazier. (A decade or so later Brazier would be well-known as the frontman of Hello Sailor. At the time of writing, the Dominion Road shop is still there, though Mrs. Brazier has retired, leaving her son to manage the store.)

After various names and line-up changes, Woolright’s band became The Entry. They found gigs in the downtown clubs and material on obscure Stax and Atlantic records, purchased from visiting merchant seamen. These records would form the basis of Woolright’s solid funky bass style.

Across town, Ponsonby-born Ricky Ball was getting a reputation as one of Auckland’s hottest young drummers. At thirteen he had bought a snare drum with savings from his paper run. Graduating to a full kit, he formed a band with a pair of brothers, Gary and Steve Clarke, and began learning British-style R&B – Rolling Stones, Pretty Things, Kinks.

The Clarke family was friendly with local entrepreneur Benny Levin, and soon the young group – first known as The Beatboys, then The Courtiers – were picking up work: weddings, parties, RSA (Returned Servicemen’s Association) functions. Though their first love remained R&B, they filled out their sets and widened their appeal with pop hits of the day.

In 1967 they became The Challenge, eventually landing a national hit single with ‘Honey Do’.

By the time they had left school, the teenagers were ready to make a career of music. Necessity dictated they emphasise their pop side, and so in 1967 they became The Challenge, eventually landing a national hit single with ‘Honey Do’ (No.2 on the New Zealand Hit Parade in April 1969).

Trevor Tombleson also grew up in suburban Auckland. He attended Avondale College, where he found he shared his passion for soul and blues with classmate Phil Key. By 1966 the pair had left school and Key was singing with The La De Da’s, on their way to becoming the country’s top band. Hoping to follow his friend into the glamorous world of music, Tombleson bought a bass (“only four strings, how hard could it be?”) and took lessons from La De Da’s’ bassist Trevor Wilson. Hooking up with a bearded bohemian multi-instrumentalist named Robbie Laven, Tombleson formed the short-lived Moses and the Munks. On vocals was Murray Grindlay, later frontman for The Underdogs and now one of New Zealand’s most successful music producers.

But Tombleson struggled with bass, so his next gig was simply as a singer. He knew just one song, the Them/Van Morrison standard ‘Gloria’, yet somehow managed to bluff his way into the band that would first become known as Cheyne, then Jamestown Union. By mid-1967 Jamestown Union were prominent on the Auckland club scene, appearing on top-rating television pop show C’Mon and opening for Eric Burdon and the Animals.

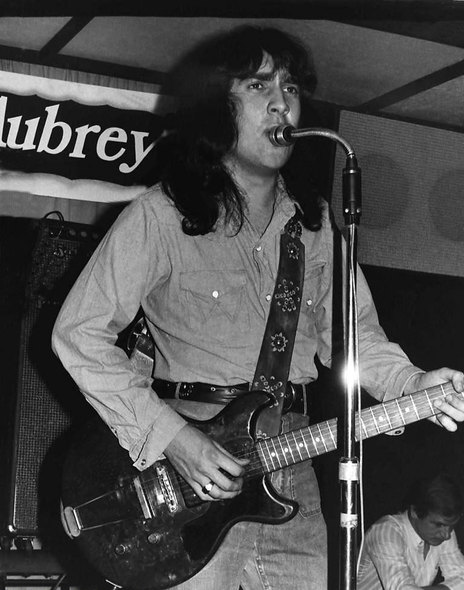

Meanwhile in the South Island city of Christchurch, an aspiring blues guitarist was at a personal crossroads. Eddie Hansen attended Christ’s College, one of New Zealand’s most venerable and prestigious school for boys. His older brother Peter was bass player for Chants R&B, one of the country’s most authentically raw rhythm and blues bands, who held court in a basement club called the Stage Door. Eddie, guitar-obsessed, would visit the club and, whenever he got the chance, get on stage and jam.

One morning Christchurch newspaper The Press ran a photo, taken the previous night, showing young Eddie on stage with the Chants. “I went to school and the next day there I was, for everyone to see. The school weren’t too happy about me, because it was against the school rules to go anywhere, let alone sneak out your bedroom window in the middle of the night to go and play in a grotty little blues club. So I got heavily chastised and told that if I wanted to play music I could play in the orchestra at school, but I declined and left.”

So Hansen became a full-time musician, with a group of fellow musical idealists calling themselves The Blues Revival. But commerce ultimately won over art, and The Blues Revival ditched the 12-bars in favour of a more commercial pop repertoire, adding lead vocalist (and soon to be solo pop idol) Craig Scott and abbreviating their name to The Revival.

By 1969 The Revival had signed to Auckland impresario Phil Warren’s Prestige Promotions and become national stars, with television appearances and a chart single (a cover of English group The Equals’ ‘Viva Bobby Joe’). They were spending an increasing amount of time in Auckland, where the biggest audiences were.

Auckland had a network of nightclubs: The Galaxie, The Top 20, The Platterack, The Tabla, Monaco, and more. The Top 20 catered to the teenybopper crowd, The Tabla was more sophisticated with “underground” groups like The Brew. But the emphasis for the early part of any night, whatever the venue and whoever was playing, tended to be on covers of current pop hits.

The venues were not licensed to sell alcohol. “Coca-Cola, Fanta and toasted sandwiches,” Woolright remembers. For those requiring something stronger there was the Hillman Lounge, as a certain notorious vehicle came to be known. It was a Hillman, driven by a sly-grogger known as Happy Jack. Recalls Ball: “The guy would turn up with his Hillman with the boot full of vodka bottles. You’d pour it into your coke, and it never quite tasted like Vodka. I think it had some chemicals in it. Very strange.”

The Revival found plenty of work in Auckland, but Hansen was not satisfied. Playing pop stars might be paying the bills, but he needed musical nourishment. Hansen: “I started getting really frustrated doing the teenybopper thing. And I started feeling that I was selling out, and I wanted to get into my guitar playing rather than being a pretty boy.

“We were playing somewhere in Tauranga, and I saw The Challenge and I really liked Rick’s energy, the way he played the drums, and we got talking. I joined The Challenge with him for a little bit. But both of us wanted to move on from that sort of thing, so we soon dropped out.”

Rick had also crossed paths with Paul at The Galaxie, where The Challenge and The Entry would often alternate sets. In 1969 The Top 20 was renamed The Bo-Peep and manager Frank Greer installed a new resident band, The Human Instinct fronted by Greer’s brother, Maurice. The Instinct had recently returned from Europe and had a bona fide guitar hero in Billy Te Kahika, better known as Billy TK. While still a teenybopper destination in the early evenings, The Bo-Peep was open until 5 in the morning and after the boppers had gone home it became the popular spot for a late-night jam.

Woolright remembers it was at one of these after-hours jam sessions that the nucleus of Ticket first played together.

Ball: “After hours everyone would go to The Bo-Peep, all the Galaxie crowd and the restaurant crowd. Every band and roadie and manager was there, all the strippers would come down from K’ (Karangahape) Road. And you could get up and have a jam.”

Woolright remembers it was at one of these after-hours jam sessions that the nucleus of Ticket first played together. “Eddie was up from Christchurch, and the guys from The Challenge were all around with their bottles of vodka smuggled in their back pockets and the jam just fell into place with Eddie, Ricky and I. I can visualise us doing ‘Knock on Wood’.”

Trevor Tombleson was also on the scene. He had received his marching orders from Jamestown Union, his onstage pranks (which would later re-emerge as a feature of Ticket) having exasperated his fellow musicians once too often. It all ended one night when a female patron, disgruntled with Tombleson for reasons now forgotten, stepped onto the stage and emptied a bag of flour over his head.

Tombleson had embarked on a brief solo career, modelling himself on such singers as PJ Proby and Scott Walker. Without a regular backing group, he sometimes used The Challenge to accompany him. When the as-yet-named Ticket started casting around for a singer, Tombleson was the obvious, if risky, choice.

Tombleson: “Eddie said, ‘this is the sort of stuff we’re looking at doing,’ and pulled out a Buddy Miles/Electric Flag album, and played me a song called ‘Them Changes’.”

It would become not just one of the signature songs of Ticket’s live shows but somehow symbolic of changes that were taking place in the culture at large. Hansen: “At that time there were a lot of changes going on, not just in music but in the way kids related to their parents. There was the whole hippie movement and the Vietnam War. Kids generally rebelling, tired of everything squeaky-clean. We were brought together in very interesting times and it all contributed to our makeup, our attitude and our sound.”

"We used to smell this stuff coming from the back of the bus, and it wasn’t bluegrass!”

— Ricky Ball

And there were drugs. Ricky had already got a whiff of that scene during his time with The Challenge. The young idols had been on a package tour, sandwiched between pop-star-turned-bad-boy Larry Morris (who had recently abandoned his successful band Larry’s Rebels for a solo career) and middle-New Zealand favourites The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band. On the road, The Challenge occupied the centre of the bus, both literally and metaphorically. The country pickers sat up front, while Morris and his band took the rear. Ball remembers: “It was about that time Larry started smoking marijuana. We used to smell this stuff coming from the back of the bus, and it wasn’t bluegrass!”

Meanwhile cannabis and LSD were becoming more prevalent in musical and social circles, particularly among the burgeoning hippie crowd. The new music arriving from overseas was like an advertisement for their use.

The covers that initially made up the repertoire of the new band reflected the altered states of the artists who had written them. Woolright: “We listened to all that trippy psychedelic stuff, Hendrix mainly. We were building the set around ‘Manic Depression’, ‘Purple Haze’, some Traffic, Sly and the Family Stone …”

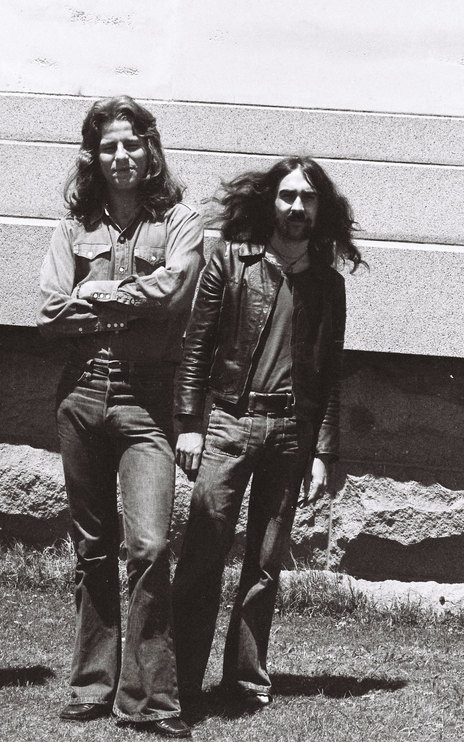

Such material required greater musicianship than the pop on which they had all cut their teeth, something the four were all capable of. But what about a name? Gone was the era of band names beginning with the definite article: The Beatles, The Challenge, The Revival. In was the single evocative word: Traffic, Cream, Free.

“There was a book,” remembers Trevor. “Eddie just picked it up, it had something in it, and he said, ‘What about Ticket?’ It was just plucked out.” The name was perfect, full of promise and possibilities. A ticket to ride, destination: unknown.

By mid-1970 they were ready to unleash themselves on an audience. Their first gig was at The Galaxie. Rick recalls being “very nervous, and I think a bit chemically imbalanced at the time. We actually were inhibited at that first gig. But we grew from there.”

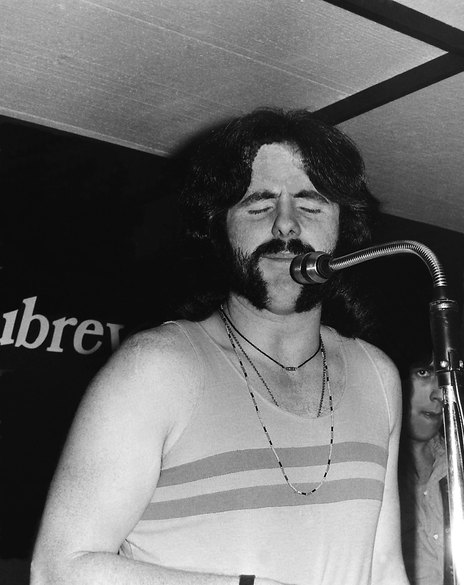

But if Auckland had plenty of venues, it also had no shortage of bands, and competition was heavy, with the poppier more commercial acts usually winning the gigs. Desperate for work, Hansen contacted Trevor Spitz, a Christchurch promoter and southern associate of Phil Warren who The Revival had worked for at a club called Snoopy’s. The club had since closed and was laying idle, but on a hearing a demo tape of Ticket, Spitz agreed to reopen as a venue for Hansen’s new band, renaming the club Aubrey’s.

Ticket headed into the chilly south as winter descended, taking up residence at a flat in Armagh St, which Tombleson remembers as “a brand new complex which had turned into a hippie commune by the time we’d left”.

Seeing the hirsute quartet in the hairy flesh gave Spitz his publicity angle. The controversial musical Hair (promoted by New Zealand-born impresario Harry M. Miller) had recently opened in Sydney amid bomb threats and eager crowds. With its headline-catching nudity, bad language, references to drugs and free love, there was debate as to whether it would ever be allowed into New Zealand. ‘HAIR HAS COME TO CHRISTCHURCH’ declared the newspaper ads for Spitz’s new house band, illustrated with back shots of the fleecy foursome.

Spitz’s cheeky campaign aroused some curiosity about the new band at Aubrey’s. Yet most punters remained aloof, feeling safer with the middle-of-the-road pop sounds emanating from nearby Mojo’s and The Plainsman.

No crowds, no money. Tombleson: “We were so hungry one night we went down to the Avon River and ran over a duck. We had to cook it all day, it was so bloody tough.”

"It was the only way we could eat, stealing food."

— Paul Woolright

They would stage raids on the kitchen at Mojo’s, risking the wrath of the club’s notorious bouncer. Woolright: “We’d sneak out the back, lift the lid of the deep freeze, take out steak, peas, potatoes, take it home and cook it all up. It was the only way we could eat, stealing food. The doorman was the kind of guy who had had a bad night if hadn’t had a fight and thrown five people down the stairs. He used to glower at us and say, ‘I’ve always wanted to punch a Ticket.’ ”

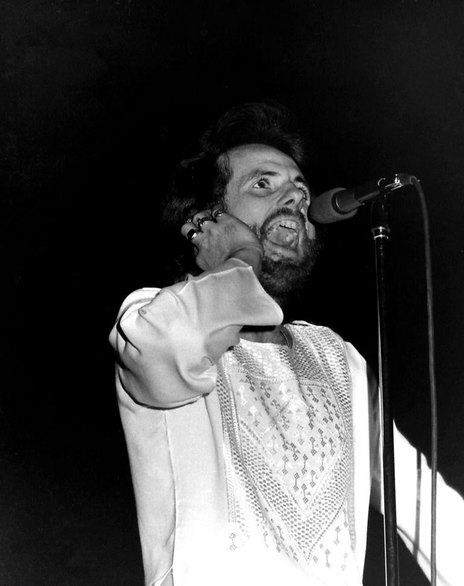

To keep the rest of the band amused, and attract the attention of any passing punters, Tombleson would devise various pranks. One night, he let a couple of female friends dress him in drag, complete with makeup, in which he performed for the entire evening.

Then one Sunday night the group’s fortunes began to change.

Hansen: “The guy who owned the Plainsman lived in Brighton, and he arrived to open the club but had forgotten the keys. There were hundreds of people outside and he and didn’t want to drive all the way back to Brighton, come back and open it, so it stayed closed. And so everyone came to Aubrey’s, the only other club that was open. I couldn’t believe it, all these people swarming up the stairs. We fired that night. That was what we were waiting for. They heard us, finally. We were hungry for it. And they kept coming back after that.”

Soon Spitz had extended their residency from two to four nights a week. Among the regulars were a growing number of American servicemen. Since signing the Antarctic Treaty in 1959, New Zealand had housed an American air base at Christchurch airport which was not only used for Antarctic research. Servicemen stationed at Christchurch, or on rest and recreation leave from Vietnam, found the sounds at Aubrey’s comfortingly reminiscent of the psychedelic rock they had known back home. For those fresh from the horrors of combat it provided a kind of sonic balm.

“They could relate to it,” says Paul. “And we could take them further away from wherever their mind was, the combat situation. That was a very important part of it.”

Another way of losing their minds was to take lots of drugs. As the airbase was not subject to New Zealand customs controls, servicemen were able to bring various illegal substances into the country.

Paul: “They’d just come straight in from Vietnam and hit the town. They’d have mescalin, acid, grass … and they just gravitated to where we were.”

The Americans provided Ticket with drugs, and a soundtrack. Trevor remembers the walls moving as he listened to Iron Butterfly’s lysergic classic ‘In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida’ in the company of stoned American soldiers.

With the growing crowds and chemical enhancement, Ticket grew louder, tighter, more musically daring, and the songs kept getting longer.

With the growing crowds and chemical enhancement, Ticket grew louder, tighter, more musically daring, and the songs kept getting longer, while Hansen’s soloing became increasingly fluid and confident.

Woolright: “Our thing was just to stretch ourselves and the music as much as we could. And the audience was right there with us. Eddie was becoming a virtuoso, Rick would start off with a drum pattern or I’d start off with a bass riff and Rick would jump in on it, or Eddie with a guitar lick, and we’d just go. And half an hour later it would still be going.”

They were also starting to perform a significant amount of original material, which they would work on during long afternoon rehearsals at the club. Soon they had enough for an album.

In August they flew to Wellington to record. They had been signed by Terence O’Neill-Joyce to Ode Recording Co., having been brought to the independent label’s attention by Del Richards, manager of Christchurch’s HMV record shop.

The long nights at Aubrey’s had seen the material well honed. All that was required was a little editing – after all, a Ticket song could last for 45 minutes on stage. Recording was handled by Frank Douglas, a studio veteran whose training as a radio engineer in the 1950s had led him to a job with New Zealand’s first record company, Tanza. In 1960 he helped build what would become HMV’s Wakefield Street Studios, where Awake was recorded. A classic Kiwi do-it-yourself-er, what the studio lacked in facilities he would make up for with ingenuity.

Among other things, he and a fellow engineer had designed and built the studio’s echo plate unit, accomplishing for fifty quid what would at the time have cost thousands of pounds commercially.

the entire album – from tune-up to mix-down – took three days, tops.

Douglas’s recording technique was straightforward, and the entire album – from tune-up to mix-down – took three days, tops. The band played live and separation was minimal, Trevor outlining a soft guide vocal so as not to bleed into the other mics. Final vocals were then overdubbed, along with backing voices, percussion and some of Eddie’s solos and second guitar parts.

A single from the sessions was released in November: ‘Country High’, backed with ‘Highway Of Love’. The A-side had grown from an Eddie riff into a group composition, with a lyric that reflected the mood of the times.

Tombleson: “See, we used to trip out or whatever, stay up all night, go and watch the sunrise. There were lots of those days. And there’s a lot of country around Christchurch, before they put the houses up.”

Ball: “But I don’t think it was all about acid. When you read the lyrics it’s also a nature song.”

The single tracks also appeared (in slightly different mixes) on the album, along with five more originals that amounted to a lightning tour of the group’s live show, with Tombleson in top voice, Hansen’s guitar dancing between funky comping and Hendrixoid solos, and the magically interlocking grooves of Woolright and Ball – heavy yet funky – propelling the whole thing.

While Ticket’s popularity in Christchurch was snowballing, word was spreading north. One night at Aubrey’s, they were paid a visit by a flamboyant Australian music entrepreneur named Robert Raymond, who had teamed up with a local promoter, Barry Coburn.

Rick: “Raymond heard the band and went, ‘Wow!’ Loved us. ‘Come to Auckland, we’ll do a show.’ He was Prince Charming in those days. He had the Stetson and the Mercedes, very impressive. I was a bit wary of him but everyone was like ‘He’s the man’ and he booked us, so we went north.”

Before the end of 1971 Ticket had shared bills with Jerry Lee Lewis and Mungo Jerry, toured nationally with Australian chart-toppers Daddy Cool as part of the Summer Rock Revival, and opened for Elton John.

Before the end of 1971 Ticket had shared bills with Jerry Lee Lewis and Mungo Jerry, toured nationally with Australian chart-toppers Daddy Cool as part of the Summer Rock Revival, and opened for Elton John at Western Springs Stadium in Auckland. The latter was the first stadium rock show the country had ever seen, with more than 20,000 punters and a bigger sound system than Ticket had ever dreamed of.

Triumphant, they returned south to headline at one of New Zealand’s first open-air rock festivals in the southern city of Gore, drawing the Southland Times headline: “After Ticket, Nothing Else Mattered.”

Awake, which Raymond and Coburn had purchased from O’Neill-Joyce as part of their management deal with the band, was released in early 1972. Meanwhile ‘Country High’ had already shot into the Top 20 the previous November; almost unheard of for a band identified as “underground”. Radio programmers turned a blind eye to its drug connotations and put the song on high rotation. They were less forgiving in the case of the follow-up, the provocatively titled ‘Stoned Condition’, while a further single – the funk-inflected ‘Mr Music’ – also failed in the charts.

By this stage Ticket’s sights were set beyond New Zealand. In March 1972 they left for Sydney. Raymond hooked them up with a residency at the King’s Cross club Whiskey Au Go Go, playing up to six nights a week, five sets a night. When they weren’t at the Whiskey or Chequers (another popular Sydney nightspot) they were on the road, establishing bases in Queensland and Victoria.

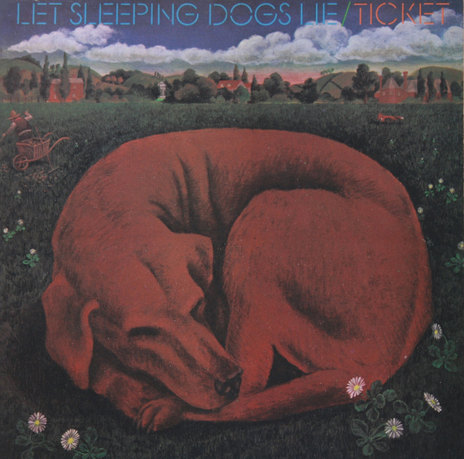

In May they went to Melbourne, where over two weeks they recorded their second album, Let Sleeping Dogs Lie. In many ways this was a more sophisticated offering than its predecessor. With Hansen taking charge of the production, the guitars were more intricately layered, and there was greater use of studio effects. Tombleson’s vocals were frequently multi-tracked, creating rich textures of unison and harmony, and the years of playing together were evident in the rhythm work of Ball and Woolright, whose drums and bass locked together with punch and precision.

The songwriting, too, was more varied and detailed. Each of the six long tracks is an exercise in light and shade, shifting in the course of a tune between driving riffs that show they enduring influence of Hendrix, and lighter, more ethereal passages tinged with folk, funk and eastern flavours. The eastern modes are particularly evident in the meditative title track, while the group’s wacky humour finds its way into the brief and mad closing cut, ‘We Love Rock And Roll!’, its minimalist lyric dissolving into a riot of psychedelic noise.

The long hours and attendant lifestyle were starting to take their toll.

But the long hours and attendant lifestyle were starting to take their toll, while the Australian club scene had brought them into contact with some marginal characters.

“A lot of the underworld used to drink at Whiskey,” Rick recalls. “One night as we were loading out, these big heavy guys, underbelly boys, were walking up the street and this other guy pulled a gun on them.”

Tombleson: “One of them was saying ‘go on, fucking shoot, go on’. And I was just thinking, God I wish I could be a mic stand right now!”

On another occasion their truck went missing between gigs, with all of their gear inside it. As Rick remembers, a local roadie, known as Mick the Shivv, volunteered to find it.

“He was a wiry little speed freak. He said, ‘Don’t worry, boys, I’ll find your gear.’ And he turned up with it the day after at the Whiskey, but the truck was full of bullet holes!”

Hansen: “I started getting worn out with the whole thing. We wouldn’t start until 10.30 or 11 at night. As the sun was coming up we’d go back to the motel and at 6pm we’d be off to play again. It doesn’t equate to a really healthy lifestyle. And then there’s everything else that goes along with it – the alcohol, the drugs. I felt like I was losing the freshness in my music. When I tried to write songs they didn’t come to me like they used to.”

Even relations between the four musicians were showing signs of strain. Hansen: “Four people hanging out together and living in each other’s pockets, you are bound to have little skirmishes. We were like brothers, and brothers have disagreements.”

That summer they also played a prominent slot shortly before Black Sabbath at the Great Ngaruawahia Festival.

The band returned to New Zealand in November 1972 to open Levi’s Saloon, Raymond and Coburn’s new Auckland club. That summer they also played a prominent slot shortly before Black Sabbath at the Great Ngaruawahia Festival, the biggest event of its kind New Zealand had seen.

But it would be the original Ticket’s final gig.

Hansen left to pursue his growing interest in meditation, soon resurfacing in the more spiritually concerned Living Force. By the end of the decade he had relocated to Australia, where he has continued to play and work as a producer.

Eddie Hansen: “Even in Ticket I was always interested in spiritual matters. It was in the lyrics, I was always questioning. And I still am to this day. But I never ever joined a team or became this or became that. Anybody tells me you’ve got to join this, give up this, be this, be that, my tendency is to turn around and walk away. That’s why I left school!”

Tombleson, too, went on to pursue an interest in things spiritual. “What LSD did for me was make me more aware and appreciate the things I took for granted. It opened doors I would never have opened at that time. But drugs are a material experience; a temporary tool to show everything material is temporary, so why hanker after it? What I concluded was you don’t have to take such stimulants. Just change your life style to accommodate and be sincere in your search.”

Hansen reformed Ticket in 1974-5, with Glen Absolum (drums), Billy Williams (bass) and Trevor Tombleson renamed briefly as Steve Gunn (it was a management idea that fell flat), although he soon reverted to his own name.

Tombleson then left New Zealand, although he briefly resurfaced as Trevor Keith in the Keef Hartley Band in the UK, and then Monsoon in Australia.

Ricky Ball returned to his old stomping ground of Ponsonby and by 1976 his drumming was providing the anchor for legendary Ponsonby rockers Hello Sailor.

Paul Woolright returned to the Auckland club scene to play with Cruise Lane and Rainbow before heading overseas in the mid-70s, working with Manfred Mann singer (and fellow Kiwi) Chris Thompson. He was also a member of Dave McArtney’s Pink Flamingos, The Legionnaires, and later, replaced Lisle Kinney in Hello Sailor and played with them until Dave McArtney's passing in 2013.

Eddie Hansen was later in Living Force and The Spyz. He's now based in Australia.

But interest in Ticket never completely went away. In the 80s and 90s, the collectors’ market for rare and unusual artefacts of the psych-rock era took off, and Ticket’s two albums – neither of which had ever been reissued – became highly sought after. At last in 2009, Awake was reissued by Australian label Aztec. The occasion was celebrated by the reunion of the original band for emotionally and musically charged launch gigs at Auckland’s Kings Arms and Christchurch’s Al’s Bar. The second album, Let Sleeping Dogs Lie, was reissued in 2014.

Ticket reformed in November 2011 for gigs at Auckland's Powerstation with Hello Sailor and Dragon

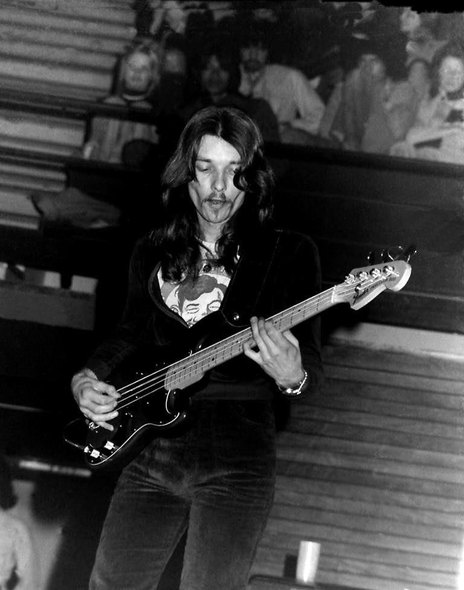

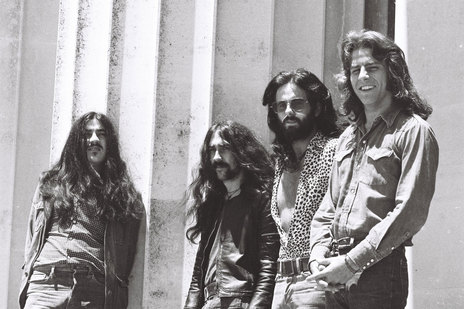

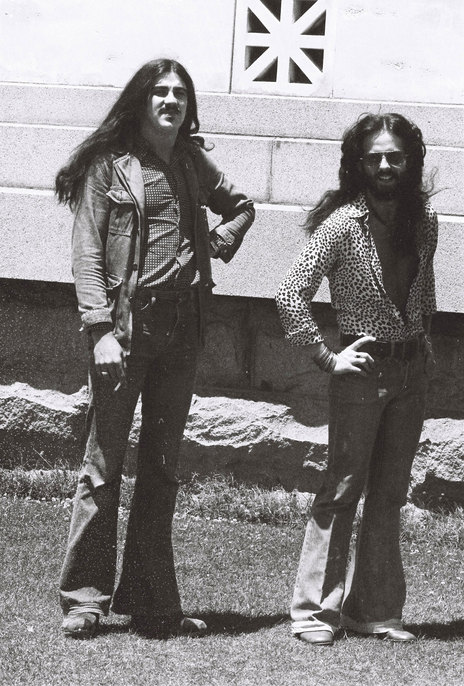

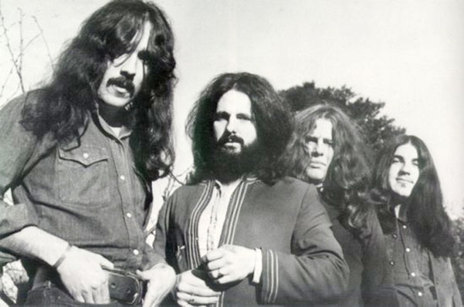

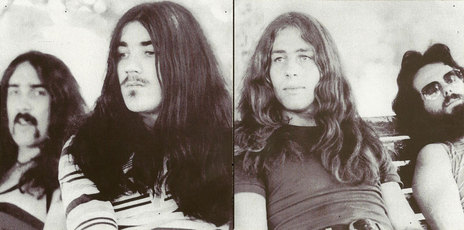

Paul Woolright - bass

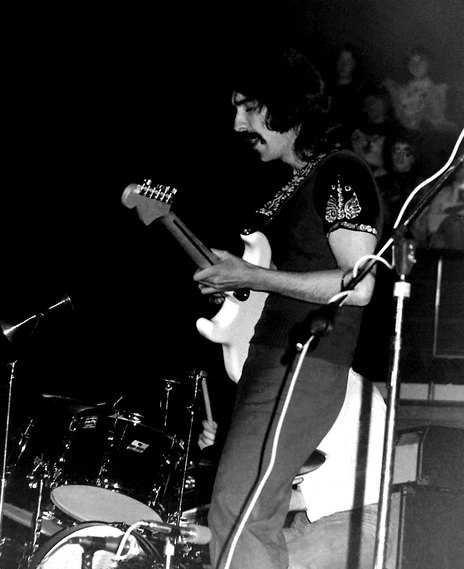

Eddie Hansen - guitar

Ricky Ball - drums

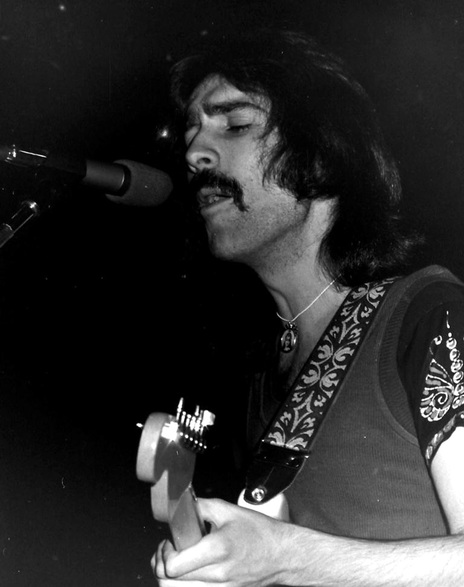

Trevor Tombleson - vocals, percussion

Glen Absolum - drums

Billy Williams - bass

Steve Gunn - vocals

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air