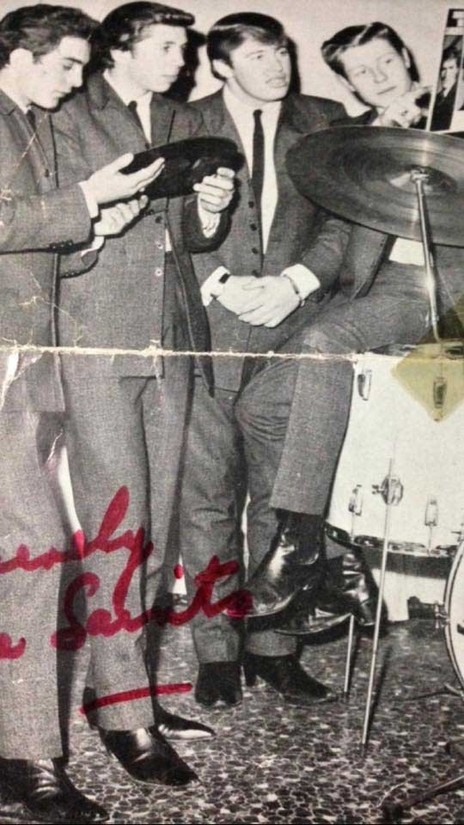

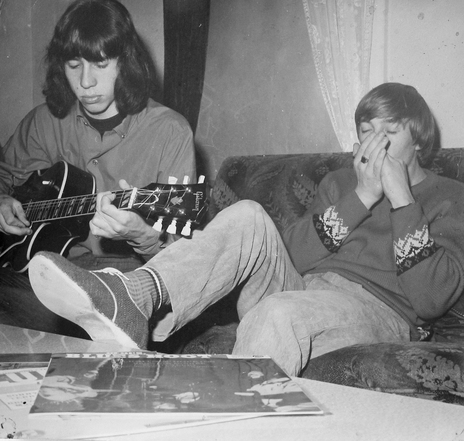

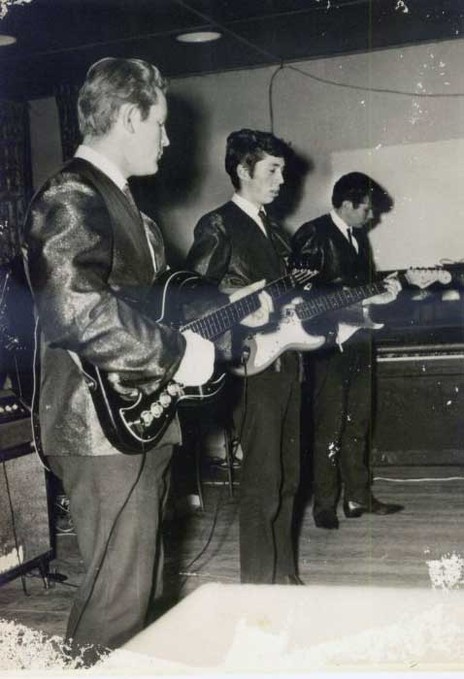

With a Commodore guitar, he studied The Shadows’ catalogue and was in his first band The Cavaliers at the age of 15. Hurley played lead guitar alongside Roy Ingram (rhythm guitar), Mike Long (bass) and Bill Weston (drums). The Cavaliers morphed into The Saints, featuring vocalist Simon Winston, guitarist Winston Cardinal, bassist Doug Rowe and former classmate Maurice Greer on drums.

“In the beginning,” Hurley remembers, “The Cavaliers only played instrumentals, The Shadows etc, because none of us could sing, or had the confidence to sing. That was never going to last, The Beatles were huge. In The Saints the vocals were at the forefront. I was the only one that didn’t sing and a lot of our repertoire was harmony songs, The Searchers, The Beatles of course, The Four Seasons. We even did Sonny & Cher’s ‘I Got You Babe’.”

Hurley left school in 1963 to take up an electrical engineering apprenticeship. When he was 16 his mother handed him the money she had saved from their family benefit. Young Dave purchased a flamingo pink Fender Stratocaster – “my folks were mortified!”

In 1964 The Saints shifted to Wellington, gaining a residency at a Petone coffee bar and playing the dance and youth club circuit.

The Saints were managed by Greer’s brother Frank, providing the band regular gigs at his Palmerston North coffee lounge and nightspot, The Flamingo. They made a name for themselves, gigging extensively around the Manawatu and further afield.

In 1964 The Saints shifted to Wellington, gaining a residency at a Petone coffee bar and playing the dance and youth club circuit. In 1965, following Cardinal’s departure, they tried their hand in Auckland as a three-piece, including a Saturday night showcase at The Shiralee.

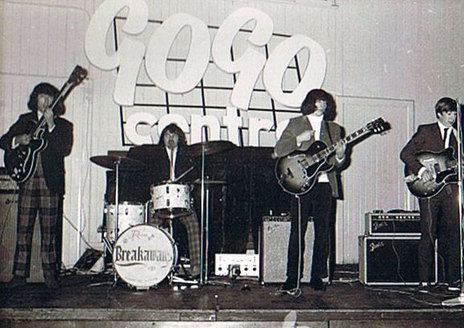

In Auckland the band’s musicianship came to the attention of two established bands, Tauranga’s Four Fours, who filched Maurice Greer, and Peter Nelson & The Castaways, who offered Doug Rowe a gig on the eve of crossing the Tasman. Back in Wellington Hurley spent the Xmas-New Year period filling in with the Silhouettes for a series of engagements in Nelson. In the new year, he was asked to replace Bari Gordon in The Breakaways.

“I’d already met the band members,” Hurley remembers. “We played on one of Johnny Cooper’s talent quests, in the Wairarapa I think, and the fledgling Bari & The Breakaways were touring with Johnny.”

Bari Gordon’s departure from the band he had formed came shortly after they had started recording The Breakaways’ debut album. “I think Bari only played on two tracks, maybe three,” Hurley says, “I play on all the other tracks for both Breakaways albums.”

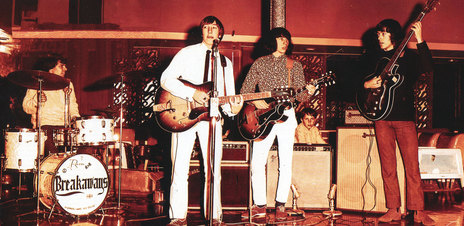

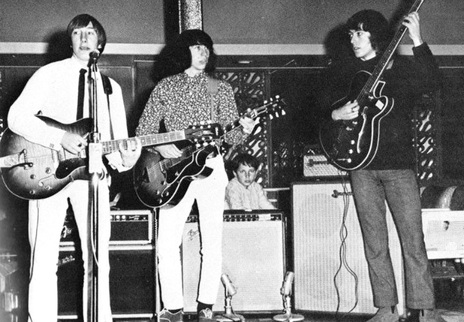

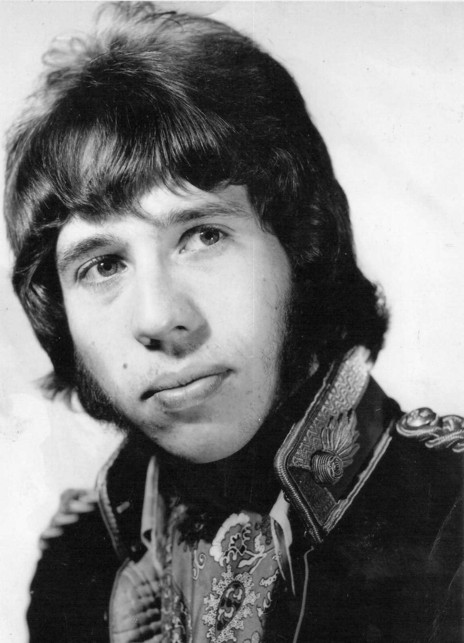

Regarded as one of New Zealand’s premier R&B bands and responsible for launching the career of Midge Marsden, The Breakaways was managed by Tom McDonald, who toured the group incessantly. “We played everywhere,” Hurley says, “from Auckland to Dunedin. We appeared on C’mon (performing ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’) and played at The Top 20 and Galaxie. We might make maybe five pounds a week, sometimes ten, other times we’d owe Tom money – he owned the transport and PA. We just existed, really.”

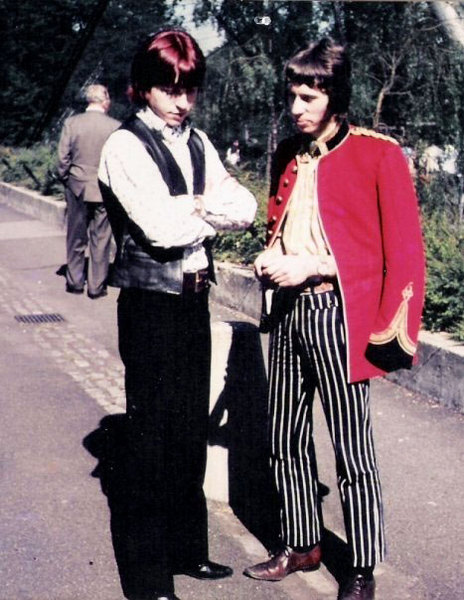

The Breakaways disbanded in December 1966 although they later reformed without Hurley, who was replaced by Tim Piper. (“I got married and got a real job, says Hurley.”) But not before spending three months in London, travelling with Frank Greer and hanging out with the recently renamed The Human Instinct. Hurley was no sooner back in New Zealand when he received a call from Maurice Greer, inviting him to replace Bill Ward in The Human Instinct. Having just become a father, he declined.

The “real job” was at a Wellington bakery before shifting to Auckland in 1968, opening his own business, a fish and chip shop on Dominion Road. Dave Hurley’s rock and roll days appeared to be behind him and his fish and chip shop career didn’t last much longer (“Too many hours, seven days a week.”)

He spent a couple of years working for Jansen, assembling amps and speakers, and there was a fledgling band featuring Paul Crowther, Paul Cuddihy, Eddie Rayner and, briefly, Alistair Riddell – “we never went past the rehearsal stages”.

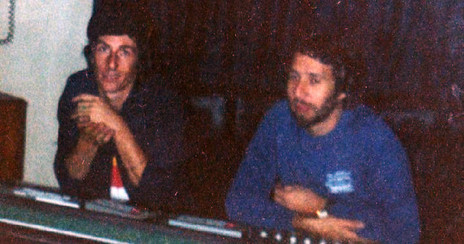

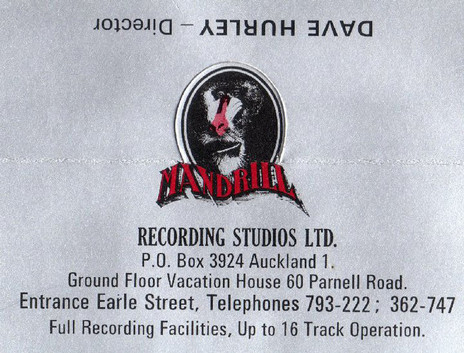

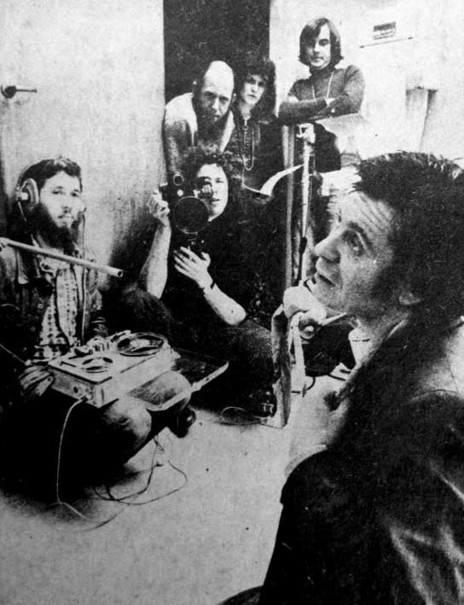

In 1973 Hurley’s life took a different direction when he got a job at the University of Auckland Audio Visual Department. The following year he teamed up with Glyn Tucker to found Mandrill Studios, purchasing a 4-track TEAC recorder and renting basement premises in downtown Auckland, where they insulated the studio with egg cartons.

Split Enz was an early client, recording demos of the songs that for their first album. Others to use the fledgling studio included Murray Grindlay and Henry Jackson bands Country Pie and Killing Floor.

Despite import restrictions in the mid-1970s, after much perseverance Hurley and Tucker were able to import a 16-track recorder and mixer, and they shifted the studio to Parnell, much to the displeasure of some other established studios.

“I was just moonlighting in the early years of Mandrill, still working at the university, but it started to get full-on, recording lots of ads and jingles, plus bands like Space Waltz, Mike Harvey. It started to grow. Graeme Myhre and Bruce Lynch bought shares in the company; Bruce’s contribution was a 24-track which had belonged to Cat Stevens.”

The second album from Auckland folk-rock band Waves was recorded by Hurley at Mandrill early on but WEA boss Tim Murdoch was unhappy with the results. Hurley recalls, "He ordered me to erase them, but I didn't". It would see release finally in 2015.

At Mandrill Hurley engineered many recordings by Auckland punk bands including The Scavengers, the Phil Judd-era Suburban Reptiles (‘Saturday Night Stay At Home’) and Toy Love’s first two singles (‘Rebel’ b/w ‘Squeeze’ and ‘Don’t Ask Me’ b/w ‘Sheep’). “A lot of the punk musicians couldn’t even tune their guitars,” Hurley says. “I had to do it for them. Despite that, there was no denying the energy of those punk bands.”

In 1981 Dave Hurley was named Engineer of the Year for his work on Dave McArtney and The Pink Flamingos’ self-titled debut album.

Now boasting a 24-track studio, Mandrill was in demand. Citizen Band and Street Talk recorded two albums apiece, with Citizen Band’s Just Drove Through Town and Street Talk’s self-titled debut produced by Americans Jay Lewis and Kim Fowley respectively.

Other heavyweights followed, including Hammond Gamble solo, the Pink Flamingos and Coup D’Etat, all engineered by Hurley. Looking back, Hurley says, “Working with the likes of Hammond, Dave McArtney and Harry Lyon probably provided the highlights of my studio career.”

In 1981 Dave Hurley was named Engineer of the Year for his work on Dave McArtney and The Pink Flamingos’ self-titled debut album.

Production work at Mandrill included Midge Marsden’s classic Connection album in 1981.

That career slowed down in later that year, Hurley leaving the Mandrill partnership to go freelance, mostly working at Hugh Lynn’s Mascot Studios.

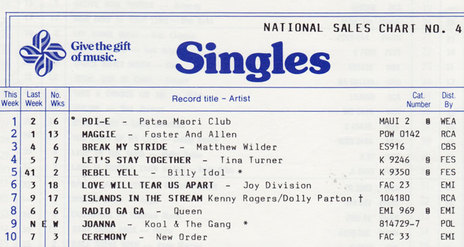

It was at Mascot that Dave Hurley engineered (and co-produced, albeit uncredited at the time – that credit would eventually appear on the album) The Patea Māori Club’s landmark ‘Poi-E’, a record that would become the biggest selling single in New Zealand in 1984.

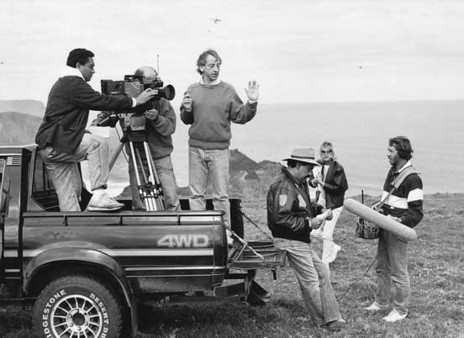

In 1983 he turned his talents to film work. Hurley’s first film credit was in 1972, as soundman on Derek, an early Roger Donaldson production, starring Ian Mune. “I didn’t realise that I was expected to work gratis,” Hurley remembers. “I’d taken time off from my university gig and had a family to feed. I insisted on getting something – it was $100 in the end.”

Since 1983, though, the film industry has provided Dave Hurley with his steadiest income. His credits including Xena: Warrior Princess, Hercules and Power Rangers. In 2006 he recorded much of Len Lye: Composing Motion at Taranaki’s Govett-Brewster Gallery.

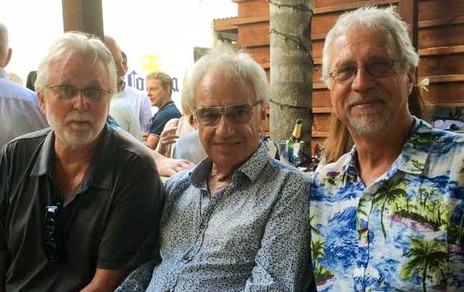

Since The Breakaways, Dave Hurley has only occasionally taken to the stage. In the late 1990s he teamed up with a loose-knit collective who called themselves The Outcasts. Members included Mike Donnelly, Lou Rawnsley and Archie Bowie, covering The Kinks, Pretty Things and Yardbirds among others. But mostly he spends his days tweaking the sound on film and television productions and planning to “hang up my head phones sometime soon.”