It was a childhood which not only supplied subjects for later songs, but helped establish a distinctive mixture of documentary-style observation and cock-eyed whimsy.

Early adulthood was similarly restless. Cape spent time teaching, odd-jobbing and studying at university, followed by freelance journalism. Religious training led to an Anglican priesthood in Kalgoorlie, Australia, lasting less than a year. Returning to New Zealand in 1954, public broadcasting proved a more permanent vocation for Cape and it was while producing religious radio programmes in Wellington that his musical activities burgeoned.

The advent of the Wellington folk music scene presented new opportunities.

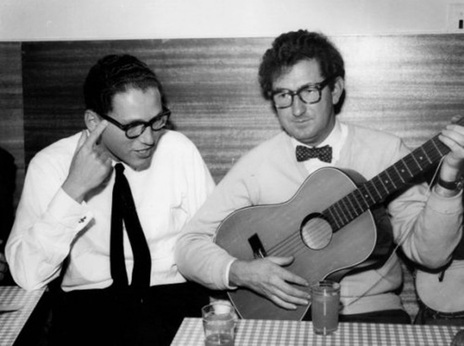

Cape had written poetry in his student days and even had a story published in Landfall, but the advent of the Wellington folk music scene, centred on downtown coffeehouses like the Monde Marie, presented new opportunities. Ballads penned by Cape found ready admirers among folkies receptive to New Zealand stories and accepting of his unusual singing voice (part lisp, part drawl). The songs also caught the attention of Tony Vercoe, director of the Wellington-based Kiwi Records, just as the label was searching around for idiomatic local material. English ex-pat civil servant and folk guitarist Don Toms was drafted in to help with musical arrangements.

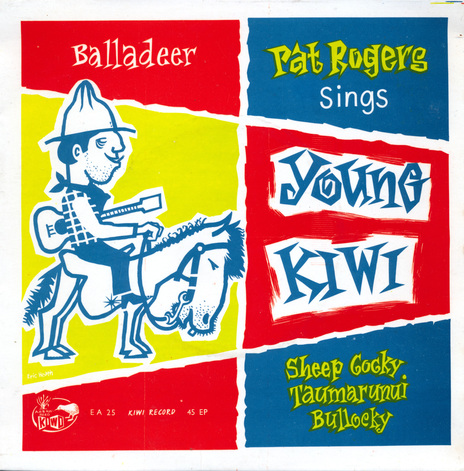

One of the first fruits of their collaboration, ‘Taumarunui’, actually ended up with tram driver and balladeer Pat Rogers. Adding his own singsong melody line, Rogers would help turn this quirky romantic lament set in “Taumarunui On The Main Trunk Line” into perhaps Cape’s most popular number – except in Taumarunui itself, where the song apparently remained a touchy subject for some years.

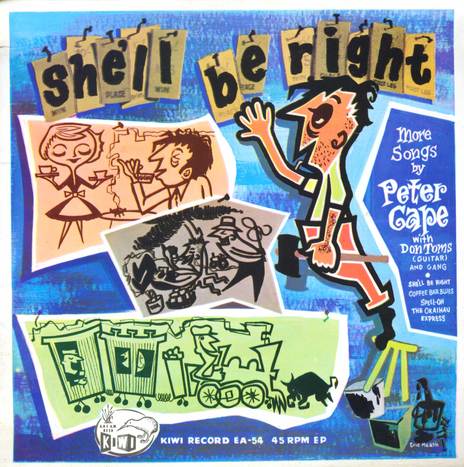

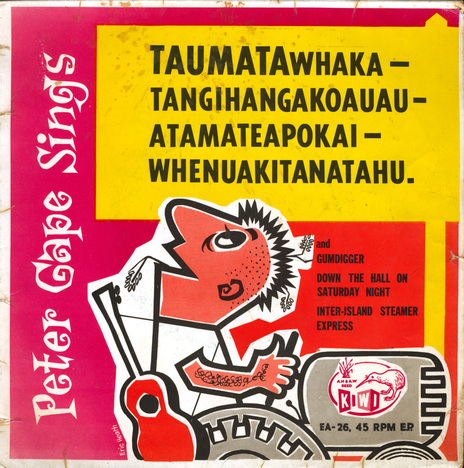

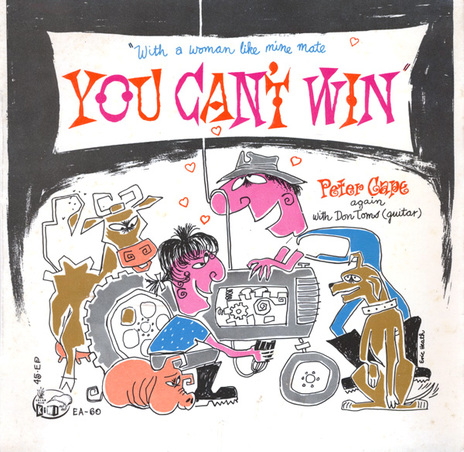

Despite his broadcasting experience, Cape was somewhat apprehensive of studio recording and his own debut EP, Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauatamateapokaiwhenuakitanatahu (1960), named for an eponymous ditty about the country’s longest place name, was instead taped in a lecture theatre at the Dominion Museum. The results were rough-edged but charming. Toms’ accompaniment buoyed Cape’s simple melodies and added amusing musical puns, providing a model for the subsequent EPs She’ll Be Right (1961) and You Can’t Win (1962).

The best remembered cut on Cape’s debut, ‘Down the Hall On Saturday Night’, exemplifies much of his songwriting achievement. In a series of deft word pictures, he satirises the typical rural “hop” of the period, the amateur dance band, the gauche provincial fashions, the male tendency to cluster by the entranceway and the quasi-legal drinking practices of the “6 o’clock closing” era:

I had a schottische with the tart from the butcher’s

Had a waltz with the constable’s wife

Had a beer from the keg on the cream-truck

An’ the cop had one, too, you can bet your life

In the liner notes, Cape took care to distinguish such pieces from both “imitation” folksongs and folksongs proper, defining them instead as “vernacular ballads”: “They’re just songs about things every Kiwi joker knows, in a language he can understand, and sing.” Cape’s ear for vernacular language shows up throughout his work. “She’d be jake”,“flat stony”; “guri”; “pikau”; “short back and sides”; “porkers”; and “shickered” are among the many colloquialisms that appear.

The habits and fashions of urban New Zealanders interested Cape, too, as heard in ‘Coffee-Bar Blues’ (“My baby sells me coffee/But that’s all she’ll do!”) and ‘Charlie’s Bash’ (“Get with the jokers in the corner/Sing all the smutty songs we know”). Other songs send up national attitudes, most obviously ‘She’ll Be Right’, where each verse sketches out a dire scenario before concluding with a note of proverbial, if naïve, optimism:

When they’ve finished off your forwards

And your backs are wearing thin

And the second spell’s half over

And you’re 40 points to win

And some hulking wing-threequarter’s

Got his teeth stuck in your shin

Don’t worry mate, she’ll be right

The majority of Cape’s work taps into the timeless settings of backblock New Zealand. The treatment is sometimes gently comedic, as with the cheeky sheepdog of ‘Talking Dog’, who tries to improve his owner’s love life (prefiguring Footrot Flats by some 15 years), while pieces like ‘Gumdigger’ provide more realistic glimpses of hard lives. In contrast, ballads like ‘Culler’s Lament’ evoke the romantic yearnings of taciturn “men alone” using metaphors drawn from the natural world:

What are you whispering, wind in the snowgrass

Combing the tussocks and smoothing them down

My love’s hair was golden, like snowgrass in summer

Your love’s left the station, she’s gone to the town

His recordings were hits – each EP sold a minimum of 15,000-20,000 copies – and tracks regularly aired on public radio.

Cape’s vernacular ballads quickly found a national audience beyond the Wellington coffeehouse scene. His recordings were commercial hits – Tony Vercoe estimates retrospectively that each EP sold a minimum of 15,000-20,000 copies – and tracks regularly aired on public radio. In 1962 he even performed on the country’s fledgling television service.

Commentators of the time regarded Cape’s songs as something of a cultural breakthrough. Together with the output of contemporaries such as Les Cleveland and Rod Derrett, his work investigated local subjects to an extent previously unheard of in New Zealand popular song. Looking back, pieces like ‘Taumarunui’ stand with Barry Crump’s novel A Good Keen Man (1960) in pinpointing a particular moment when the “cultural cringe” about hearing our own vernacular voices and accents receded – for a time at least.

But it wasn’t long before Cape himself moved on, once again. “He had said what he wanted to say in that form,” according to Vercoe. The demands of becoming a senior producer at the NZBC's Wellington television studios in 1963 may have been a factor, too. Cape increasingly turned to book writing as a creative outlet, authoring several works on New Zealand arts and crafts before dying unexpectedly in 1979 at the age of 53.

Peter Cape’s legacy in New Zealand popular music belies his relatively modest oeuvre of around 25 songs, three EPs and a 7-inch single. Artists as diverse as The Human Instinct, Danny McGirr and When the Cat’s Been Spayed have covered his compositions, while Phil Garland, Mike Harding and others have kept the flame alive on the folk club circuit. No other local songwriter is represented in so many literary anthologies. Cape has also decisively influenced the development of New Zealand popular humour. Items like ‘She’ll Be Right’ and ‘The All Black Jerseys’ blazed the trail for John Clarke’s 1970s icon Fred Dagg, and echoes of Cape’s rural surrealism and Kiwi self-mockery can be heard in the work of the Topp Twins, the Front Lawn and others, even Flight of the Conchords. Poking fun at ourselves has never been out of style.