AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Wahanui Wynyard

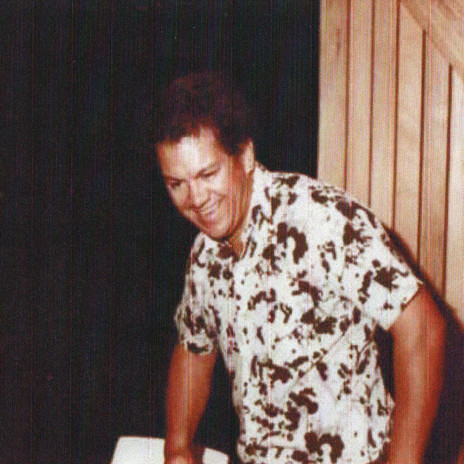

Few names from the era are held in such regard by collectors and yet the man himself remains largely unknown to a wider public and, given his reputation, extremely unassuming and self-effacing.

In the late 1950s, Wahanui was a teenager in Northland; he was born in Whangarei, but raised in Russell in the Bay of Islands. In 2017 he told AudioCulture, “My father was from a little village between Russell and Kawakawa called Karetu. My mum was from Moturoa, which is one of the small islands in the Bay. I think she was from Totara North originally, she used to row from the island to Rawhiti for school every day.”

When Wahanui left school in 1960, his mother asked him what his plans were. He shrugged and said he had no idea, so she suggested he write to the three branches of the armed forces, and to the state broadcaster, the NZBS (New Zealand Broadcasting Service). Wahanui did this, and to his surprise was accepted by all of them for training.

“I asked myself, who pays the most money and I thought it would have to be the NZBS. At the time, I had no idea what I was getting into, but the Army and Navy would have me marching around with a gun on my shoulder. I wasn’t interested in that. I had no idea at all what the NZBS would have me do, but I went for an interview at 1XN and decided that’s what I was going to do.”

There were no vacancies at the Whangarei station, but they wanted to test his possible skills so he was asked to collate a show called Music To Work By, a music-only show of listener requests played daily on the station. The show had to fit the 30-minute time slot and the songs had to flow together. With little more than instinct to guide him, the teenager passed the test with flying colours and was sent to Auckland for another interview, accompanied by his mother. There, after some persuasion from Mum, regional engineer Gordon Baxendale offered Wahanui a job at the NZBS studio in Shortland Street, Auckland.

At age 18 Wahanui Wynyard was a trainee engineer, albeit one who knew little about the job he was supposed to do. But he was eager to learn. “They did the usual with me,” he laughs, “‘find me a left-handed screwdriver and a left-handed hammer and charged-up condensers’. I would say ‘I know nothing about this sort of stuff’, which was true. I did this for four months and then I was sent to Wellington for a training course.” At head office in the capital, the NZBS management would decide if the young trainee would continue on the technical side or move to another role, an on-air DJ perhaps.

In Wellington, Wahanui discovered an aptitude for recording. “I said ‘I want to have a go’. I was better at it than any of the others. They were more interested in how a phone works, how an amplifier works, how a console works … and I was, fine, you go do that I’ll go and do this. But, I never got to do any [recording] until way, way later.”

Back in Auckland, at Shortland Street, Wahanui was put into the recording studio beneath 1YA, transferring tapes, making transcription discs and acetates, and working on current affairs shows, and sports and farming programmes. He also assisted recording radio dramas. “You have one person down one end of the studio doing footsteps and opening/closing doors and ringing bells, and all the other sound effects. I was placing the microphones for these, and I thought this is great, one day I’m going to get in and do these plays.”

He found himself working with the reigning BIG bands of the era.

Many of these were made by a disc jockey from 1ZB, but the results were uneven and unbalanced. The DJ was removed and Wahanui was asked to try his hand. The results were impressive. “So I got to do it. I moved up a little bit further.”

Intrigued by some of the Hawaiian sounds performed by Bill Wolfgramm’s band that he was transcribing for the BBC, Wahanui asked where it was recorded. When told it was done at the 1ZB Radio Theatre across town in Durham Lane West, he approached the studio’s producer, Don Patton, and asked if he could sit in. He soon found himself working with the reigning big bands of the era: "I soon found myself working with the big jazz bands of Bernie Allen, Crombie Murdoch and Merv Thomas, The Oswald Cheeseman Orchestra, Bill Wolfgramm and his Hawaiians, the wonderful vocals of Kiri te Kanawa, the Lew Campbell, George Campbell and Don Branch Jazz Trio – we even did a comedy show with audience called The Life of Fred with Peter Engebretsen producing."

It was the era of quarter-inch mono tape and studio gear: primitive by later standards. This meant recordings were usually done in one take. “When it was done, they’d ask, ‘any mistakes?’ ‘no’, ‘right, that’s it – next’.”

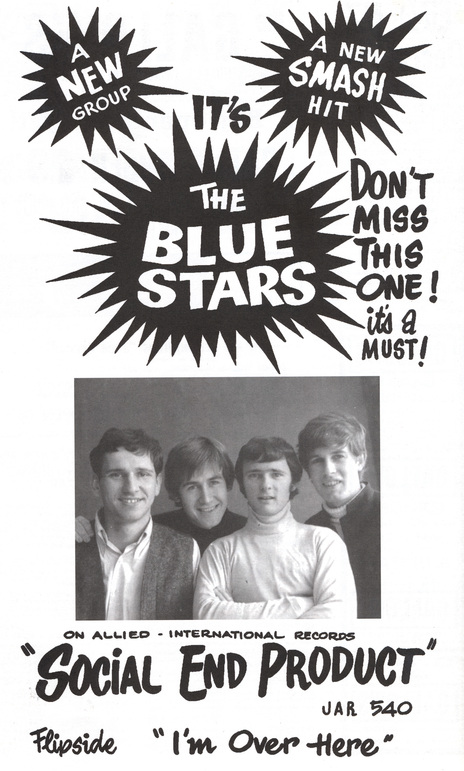

Poor pay, his own growing skills and a desire to experiment in the studio –albeit restricted by the limitations of the equipment – led to Wahanui taking up offers of extra work in the Shortland Street studios (in April 1962 the NZBS became the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation). One of the first sessions was with a young band from Auckland Grammar, The Bluestars, who managed to hurriedly record four songs in mid-1965 at 1YA’s studio before an orchestra arrived to take over the room.

These recordings were sent by the band’s manager to Decca Records in the UK and two of those songs, ‘Please Be A Little Kind’ and ‘I Can Take It’, were issued as a single there in December that year. While the single was not a hit – even in New Zealand when it was released in early 1966 – the B-side of the single was a pointer towards things to come. Although ‘I Can Take It’ was a little more R&B than the records Wahanui Wynyard would later become known for, it had a similar unfettered momentum and raw ferocity.

Around the time the debut Bluestars’ single was recorded, Wahanui Wynyard’s career took an important turn. “We used to have people come in to do advertising work which would then be transferred to acetate by us … there was this bloke from Astor Studios, which was just down the road in Shortland Street, to do these [transfers]. I used to time them and have a listen to them, make sure they sounded all right and things like that. And he said to me one day ‘are you interested in doing some after-hours work?’ I said ‘yeah!’ and so I started doing stuff with him at Astor.”

Shortly afterwards Astor’s city recording studio moved to the new Peach-Wemyss-Astor film facility in Nugent Street, Grafton (although the sound studio was always known as just Astor to the recording industry). Wahanui was offered a full-time job there, which he accepted.

Astor had a close relationship with George Wooller’s Pye/Allied International/RCA recording group and Wahanui quickly developed a friendship with their A&R boss, Fred Noad, which meant he was regularly approached to record artists from their roster over the next five years. Noad was adventurous in his signings and Wahanui was often asked to work with young artists keen to expand their sounds in the studio, in what were increasingly experimental times.

“He said, ‘where the hell did you get that from? You can’t do that, it’s illegal!’.”

It was, however, a friendship tested by Wahanui’s habit of creating acetates of the current radio hits for private use. He would borrow the singles and put the current hits on a single long-playing compilation for his own use. “People used to love them because they had never heard anything like it. I took it down to Fred Noad one day and I said, ‘look at this’. He said, ‘where the hell did you get that from? You can’t do that, it’s illegal!’.” A suggestion that Pye create similar albums for public consumption was dismissed out of hand. In the 1970s the Solid Gold Hits collections, created by PolyGram’s John McCready for the record companies, would sell hundreds of thousands of records and make the industry a substantial sum annually.

At Astor, Wahanui Wynyard was doing advertising work during the day and recording bands and other artists during the evening. He was also working on films, including incidental band music for John O’Shea’s Runaway (although this preceded his full-time job at Astor). Among the bands recorded were The Chelsea Beats, featuring a young Red McKelvie (his first documented credit at Astor).

The Bluestars meanwhile had, without Wahanui, recorded a second single at Mascot Studios for Decca, but it was rejected by the UK company, who dropped the band. The Bluestars returned to Wahanui, now at Astor, to try again. In September 1966, the band and the producer recorded their landmark proto-punk classic ‘Social End Product’, the song that would forever establish the reputations of both the band and Wahanui Wynyard. Nothing like ‘Social End Product’ had been recorded in New Zealand before: it is a searing performance and a challenging production from the opening lead riff, to the volley of screams that close it two and a half minutes on. Globally, it made The Pretty Things sound like Herman’s Hermits and it has been heavily bootlegged and compiled in the decades since. Magazines and albums have been named after it, and one copy changed hands in the United States for US$1300 in 2016.

However, Wahanui told AudioCulture in 2017, he can barely remember the session. “I can’t remember what I did … I don’t think it was accidental, I think I think the guys came in with something they would like to hear and they said ‘can you reproduce this?’ and I just reproduced it, that’s basically it.

“It was all done on mono. We had two tape recorders and we would bounce sounds backwards and forwards and overdub. However, we were just losing quality the whole time it was being transferred. Sometimes we would end up with eight or nine dubs across, with extra things going on all the time. It gave it a noisiness ... raucousness!

“You would do a backing track – sometimes you would do a backing and a vocal track together – and then you would dub what you needed.

“We just went with what the band was playing, it wasn’t being put through effects or anything, it was just capturing the performance. We had no choice anyway. You know, that’s all we had and we had no way of changing it. Once it’s on there, that’s it.”

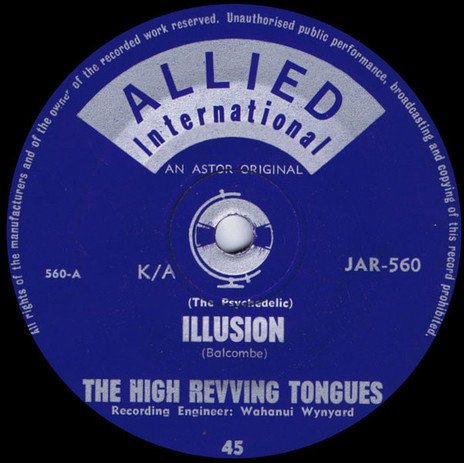

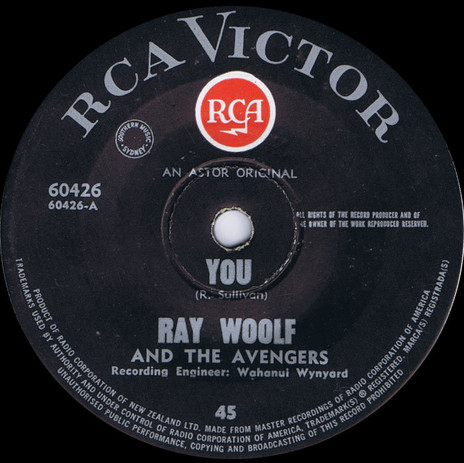

Whatever was done or not done, there was a uniformity of sound now coming from Wahanui Wynyard’s desk at Astor and a string of classic sides recorded by him appeared on RCA, Allied International, Pye and Benny Levin and Russell Clark’s new Impact label over the next years. The Smoke, The Hi-Revving Tongues, Dallas Four, The Principals, Larry’s Rebels, The Music Convention, Le Frame, Tomorrow’s Love, The Fair Sect, The Challenge, and Ray Woolf And The Avengers are just a few of those with Wahanui’s name on the label, either as engineer, producer or “Recorded By” (in 1960s New Zealand, credits were largely interchangeable). Many more – including releases known to include his work – don’t have label credits and Wahanui admits he’s often just forgotten.

“When I was in Sydney, a couple of guys came up to me and shook my hand saying, ‘good to see you again’. I didn’t really know who they were but then they started talking about things and I thought, ‘oh yeah now I remember’.”

“We just tried our best to do to get it out sounding as good as we could with what we had to work with.”

Wahanui Wynyard recorded all of Ray Woolf And The Avengers’ singles. He recalls that they were a lot of fun. “[Ray Woolf] used to come in with records he got from his mother or his brother or something and he’d say, this is one I want to record, and they would have a particular sound they wanted to get. I’d say ‘Ohhhh! ...’ because I had nothing to help me. I’d just have to work out ‘how did they do that? How do you expect me to do this? I’ve got nothing here apart from these two tape recorders’. But you’d get it down and then you’d give to someone like [presenter and radio DJ] Peter Sinclair. I used to do these pop shows at Astor for him every week and I’d throw one in there and it sounded like all the other records that were coming out of an AM radio speaker … once you got it on an AM station you really couldn’t tell the difference between that the other ones and what we were doing. But you would soon notice it when you played it on a record player.

“We just tried our best to do to get it out sounding as good as we could with what we had to work with.”

In 1967 Astor purchased a 4-track tape machine, offering a huge jump in sound. Levin and Clark pushed for it and the first recording was Larry’s Rebels’ ‘Do What You Gotta Do’, followed by the soundtrack to Andy McAlpine’s surf flick, Children Of The Sun, featuring Hamilton band The Music Convention. The psychedelic, sitar-driven surf instrumentals were written by the band and then recorded and slowly constructed in the necessary sequence for the film, with Wahanui editing the tapes using razorblades. An extended 7” EP was drawn from the soundtrack and issued by RCA, but it sold sparsely given that even the pirate station Radio Hauraki found it challenging. In the decades to follow it would become yet another expensive collectable.

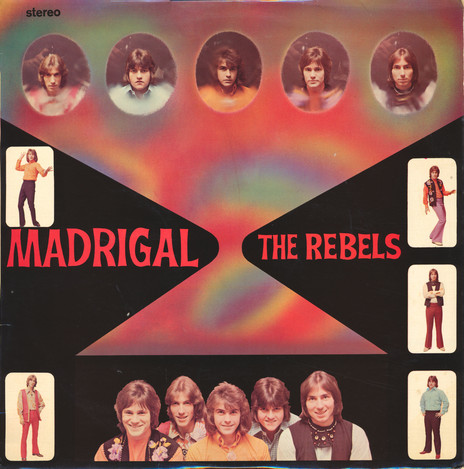

As the 1960s rolled into the 70s, Wahanui Wynyard kept up a hectic pace, as Astor was the go-to film studio. “I was just so flat out. When you have a film suite next door and you are doing soundtracks for them as well as doing things for radio – it was very busy. And then at night-time, it was time to make records!” In March 1969, he recorded Madrigal by The Rebels (post-Larry Morris). It was done in under two days because the band was off to Australia, but in 2016 it was hailed by writer Nick Bollinger as an essential New Zealand album. Capturing soulful vocals perfectly was now a Wahanui Wynyard trademark, and the reviews at the time noted this over and over.

A key recording credit that Wahanui has little memory of is one side of The Human Instinct’s era-defining blues-rock album, Burning Up Years. The band had become a tough blues trio featuring Billy TK’s formidable guitar. Burning Up Years was the first hard-rock album recorded in New Zealand, and, yes, it too is very collectable now. Recorded at Astor, the band and Gary Potts confirm that Wahanui did the night sessions, whilst Potts did the days. A recent reissue has added both Wahanui Wynyard and Gary Potts to the credits, an oversight when it was first released.

This intense work schedule at Astor probably could have carried on for a long time, but in 1970 Wahanui took a call that would change his life.

“I got a phone call from an old mate I used to work with at the NZBS. He’d gone to Australia and produced the first commercials for the Ten television network. He rang me one day and said, ‘What are you doing?’ ‘Working’, I said, and he asked, ‘Do you want to come to Australia?’”

“He said to me that [Sydney studio] United Sound were looking for an engineer. I said, ‘Yep!’.”

United’s boss Ron Purvis soon arrived in Auckland and immediately offered Wahanui a job. His initial response to the offer was, “To leave I’ve got to have something pretty concrete. I’ve just bought a home and we’ve just had our first child: it’s a big move …” Purvis responded with “I’ll book your fares, all your family, all your luggage, six months accommodation and $200 clear a week".

Wahanui was earning $36 a week in New Zealand and needed little persuasion. He moved across the Tasman in July 1970, on a 12-month contract.

In Australia, the money may have been good but the job had its frustrations. “Nobody would work with me. [They] didn’t know who I was. I was not on the list of good engineers.”

However, the studio gear available compensated for that somewhat. “I just could not believe what I was seeing. There was this huge room which could seat about 70 people, a big vocal booth, a 35mm projector, a huge screen, a 40-something channel console, an 8-track recorder, four huge Tannoy speakers in front of you and two stereo master track recorders.

“And there was this guy with red hair all the way down to the back of his bum, holes in his jeans … I couldn’t believe it, I thought who is this guy? He turned out to be one of the best engineers in Australia at the time [Spencer Lee]. He was doing a mix of a track for [Australian country singer] Lee Conway. He said, ‘Have a listen to this and tell me what you think’. He put it up and I just could not believe how good it sounded. I said, ‘Bloody hell, where did you do that?’ He replied, ‘In there’. It was just mind-boggling. I asked, ‘Did you ever listen to any of the stuff I did?’ and he said, ‘Yeah, I loved it!’”

However, the next six months were spent doing dubs, copying commercials for radio stations and suchlike, with Wahanui not getting near the big console he’d seen. Frustrated, he decided to do something about it. “I thought I’m not going to be stuck in this room all the time, I’m going to go and learn how to run that big bloody room in there. So, I used to go into that big room every day there was a session on and I’d set him [Lee] up. I’d ring him, and say, what’s your setup for today and he’d say what it was and I’d set it up for him. He was very appreciative of that and he showed me how to work the console.

“I also learned how they did things: it was nothing like I’d done before, microphones about three or four inches away from instruments whereas in the old NZBS system you were trying to get an overall sound so I’d never done that. It was a really ‘present’ sound.”

His chance came exactly six months to the day after he’d arrived in Sydney when the studio owners had an argument with a client. Overhearing the fuss, Wahanui asked who the problem was with. Told by the receptionist that it was [composer and conductor] Patrick Flynn, he said “I know Patrick, I did a job with him at Peach-Wyness-Astor. He had a big orchestra on the stage and the band was in the other little studio, it was really good, they loved it – he loved it – just tell them that I’ll do his job for him.”

Flynn shouted back, “I’ll see you at 11 o’clock after I’ve finished this Jesus Christ Superstar concert.” The job was for Air New Zealand, and despite it taking far longer than expected, the client was thrilled with the result. Word soon got around …

Three weeks later, a caller from advertising agency Leo Burnett asked, “Are you the Māori prince from New Zealand? … You did a job for Patrick Flynn, we’d like you to do our job for Ampol Petroleum Service Stations, a full-on job, promotions, commercials for television and radio: the full promotion.”

Wahanui was given a raise but as the work flowed in he was unable to find the studio time at United he needed and eventually went freelance. Band work arrived too, and the name Wahanui Wynyard appears on the credits of a substantial number of Australian records in the 1970s and 1980s, including Australian glam band Hush (their hit debut live album), The Johnny Rocco Band (featuring New Zealand vocalist Leo de Castro) (recorded at Atlantic Studios), Norman Gunston, the Breaker Morant soundtrack, Bob Hudson’s huge hit ‘The Newcastle Song’, Marcia Hines, Jon English, and several country hits by Digby Richards. Even Kamahl benefited from the Wahanui Wynyard touch.

Two recordings made by Wahanui dwarfed any others commercially. The first of these was the theme to the globally successful TV series Home and Away, featuring expat vocalist Mark Williams. A contractual dispute meant that it only had limited release on record in Australia, but it was a hit in the UK. For years, Wahanui was responsible for much of the incidental music in the show, working with another notable New Zealander, Mike Perjanik (who wrote much of the music, including the Home and Away theme) with whom he had worked steadily since arriving in Australia.

Other New Zealand musicians also featured professionally, one of these being the pianist Julian Lee and it was with Lee that Wahanui recorded the biggest-selling release of his career: “A guy from K-Tel [Theo Tambakis] came in one day and said, ‘I want to record a Hooked On Swing album, who do I use?’ I said the two best guys would be Julian Lee and [Australian jazz trombonist and pianist] Jack Grimsley so that’s what happened.” Hooked on Swing went on to be an international smash for K-Tel, charting in almost every country in the world and selling millions of records.

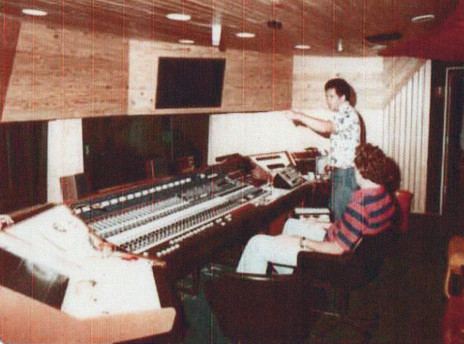

By 1977, Wahanui Wynyard was over running from studio to studio. “I was sick and tired of rushing around all over the place, and I thought if I can get a studio that I can go to all the time that would be better for me than going from one side of Sydney to the other: I was getting sick of doing that.” A visit to Albert’s, the Australian production house and music publisher founded by Jack Albert in the early 1900s, and home to songwriters Vanda & Young and AC/DC, offered a solution.

“Bruce Brown, the manager – an engineer/producer too – said to me, ‘We’ve got three studios here’. One was the main one which he worked in most of the time, and there was Vanda & Young’s studio which they only used at night, and then downstairs they had another little studio which was used for doing overdubs. All had 24-track digital recorders. I went there and I did one job and I thought, ‘Oh this is bloody good’ and the clients loved it. It was new and it had a good vibe about it, so I started working there. My clientele started building up, I was getting really busy and I didn’t have to go very far: I just went in at 9am and didn’t leave until the last person left, which could be nine o’clock at night or one in the morning.

In Sydney, Wynyard was so in demand that Albert’s Publishing Company built him a studio.

“The first year there I pushed Bruce out of his studio, basically. He used to come down and work four days a week, and I used to do night stuff on the other days. Friday, Saturday, Sunday. He’d be back on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, Thursday. I said to them one day, ‘Look, I’d like to do a bit more time, I’m not able to finish jobs completely’. So, then I started on Monday and did the whole week and the only time he could get in there was at night. Bruce then said, ‘This is not going to work, we’ll have to come to some other arrangement’, So they built me my own studio in 1983, Studio 4.”

Later in the 1980s, when the studio moved, it was fitted with a new Fairlight CMI, the Australian-designed digital synthesiser/sampler that defined much of the sound of the 1980s. It was both a blessing and a curse. A quantum leap from the mono tape-to-tape dubs of the NZBS and early Astor days, the Fairlight and similar technologies would also eventually spell the end of the old, large, studio production houses that dominated audio and video sound for decades. They were becoming redundant in a world where much could be created digitally, often on increasingly compact gear. An era was ending.

“I don’t think there are many engineers left who would know how to do what I did,” Wahanui Wynyard told AudioCulture in 2017.

When the old Albert’s studios were sold in the late 1980s, the company moved to much smaller premises in Neutral Bay. In 1990 Ted Albert, the grandson of the founder and the visionary who had driven Albert’s massive success in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, passed away. As Wahanui recalls, “the end was nigh.”

In 1991 he was let go by Albert’s and left the recording industry, moving into a new career as a domestic engineer. Wahanui Wynyard now lives near Brisbane, retired and justifiably proud of what he achieved in the years since the teenager left the Bay of Islands to become a trainee audio engineer almost 60 years ago.

The vast catalogue of Albert’s was sold to the German-owned multinational media group BMG in 2016 and the company that employed Wahanui Wynyard no longer exists. Astor Studios, or PWA Film Productions Limited as it was later known, left the industry in the 1980s. The Shortland Street and Durham Lane studios of the NZBS and NZBC are long gone: the former repurposed, the latter demolished. The surviving publicly owned New Zealand radio stations, in the form of Radio New Zealand, still record New Zealand artists, usually now just for live to air broadcast (RNZ’s last Auckland studio, the Helen Young Studio, closed in the late-2000s).

Wahanui Wynyard is one of the giants of the New Zealand recording industry. His recordings, initially made on rudimentary equipment, would have tested the even the most experienced technicians of the day, and yet the discs he made by bouncing mono tracks back and forth, trying to both preserve quality and capture the unfettered rawness of the performance, have been lauded around the world. The man himself is modest about his achievements, but those who have followed are aware of the debt.

Wahanui translates to 'big mouth', and the name came from his grandfather, who was given it because he was a great orator. The late Canon Wi Huata, from Ngāti Kahungunu, told Wahanui that "whilst you are not a great orator you are a maker of great sound."

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air