AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Butler

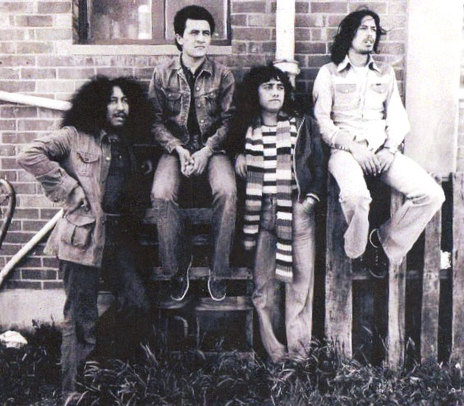

Their fusion of psychedelia, progressive and blues-rock shone in a live setting, and Butler became a highly popular band on the national campus circuit. One of the few all-Māori bands of that era, the story of their formation is one of the most fascinating in NZ rock.

The creation of Butler was both spontaneous and unconventional. A typical New Zealand rock band circa 1970 would comprise high school pals or early twenty-something Pākehā males, jamming in a garage or rehearsal space. The bonds between the four members of Butler were forged in the tobacco fields of Motueka and a drop-in centre in Christchurch.

The bonds between the four members of Butler were forged in the tobacco fields of Motueka and a drop-in centre in Christchurch.

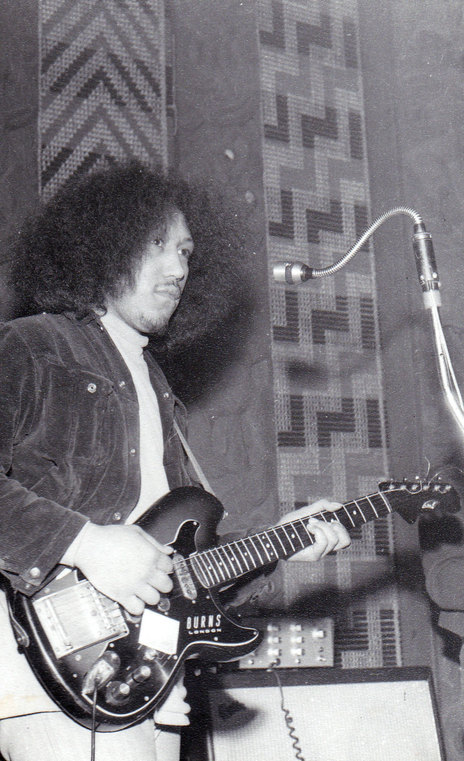

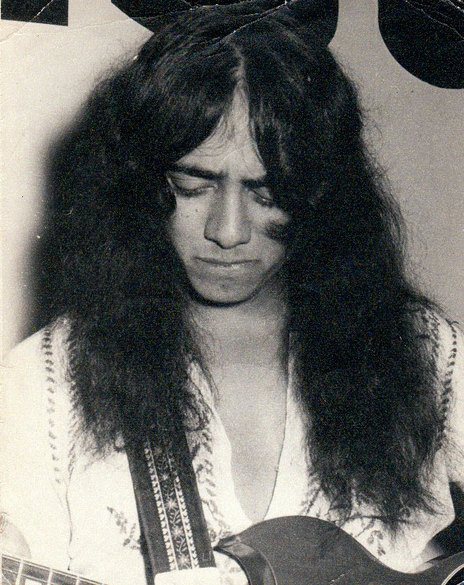

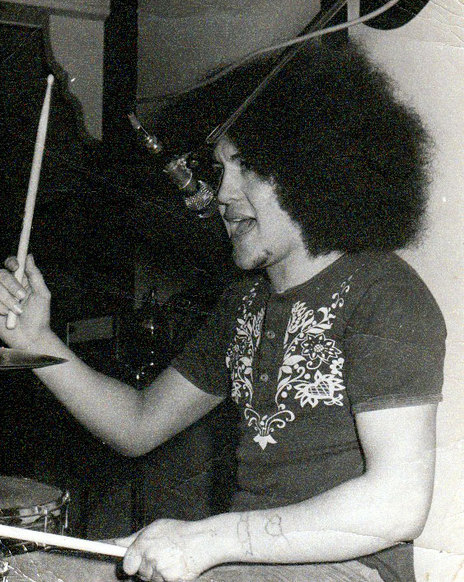

Butler comprised four Rotorua area born and raised Māori teenagers. The original (and only) line-up comprised Steve Apirana (guitar, vocals), Heidi Warren (guitar, vocals), Angel Adams (bass), and Hori Sinnott (drums).

In a 2013 AudioCulture interview, Steve Apirana, Butler's acknowledged leader, relates the story of the band's formation. “A bunch of us from Rotorua went down to Motueka to work in the tobacco crop. Back then there was a scheme where the government would fly you down. If you stayed working for six weeks, you didn’t have to pay back the fare. They were going to fly us back but we decided we’d try living in Christchurch. We didn’t know how cold it’d get! We were basically street kids. We’d sometimes crash on people’s sofas for a few nights, but we often slept in the park too."

To find warmth and a cheap meal, the four guys and their friends began hanging out at The Open Door, a Christian drop-in centre on Tuam Street. "It used to be an old pub and it was donated to the Anglican Church," says Apirana. "There were three centres like that in central Christchurch, but we chose this one because it had band gear there."

In an interview with English music website Cross Rhythms in 1997, Apirana recalled the centre. "It was the only place that would let smelly-looking kids come into their buildings. We were heavily into rock music and they had a dilapidated drum kit, an amplifier and a couple of guitars. They let us play on them and we thought we were the Rolling Stones or somethin'. We would toss a coin to see who was going to play the drums because no-one wanted to play the drums, we all wanted to play the guitar. We taught each other how to play. Being brought up in a Maori community, just about everyone would have a guitar and just about everyone sings. We would have a lot of parties ... and that would be where you learnt to sing as well."

Apirana started playing guitar at age 15, and a year later he and Warren (who was a year younger) decided they'd start a band. Their dream, however, only coalesced with these jams in Christchurch. "We approached the guy who was running the centre and got him to open it up on a night it was not normally open so we could practice," Steve told Cross Rhythms. "Three days later, the son of the minister offered to be our manager. Here we were, a band formed in three days, nowhere to play, only a couple of instruments, but we had a manager!"

"He saw something in us," says Apirana. "He said ‘see how far you can take this'. To me, it was just a dream. I didn’t expect anything from us. We started practising more and saving up to get proper gear within a year. He kept us on the straight and narrow, as we were all over the place emotionally then.”

Perhaps not totally straight and narrow, he mentioned to Cross Rhythms. "We still got into a bit of trouble, but we stopped the crime side of our lives. I'd been in trouble all my life, sent to boys homes, family homes and stuff, and I just carried that into my adult life."

The story behind the choice of band name has a tragic side.

There was safety in numbers for Apirana and his fellow street kids then, he recalled. "There were eight or nine of us, so we never got bothered by anyone ... except the police."

The story behind the choice of band name has a tragic side, says Apirana. "Butler was one of our friends, a street kid too. He was maybe going to be our singer. He was a good-looking guy with a big afro. He’d be out on photo shoots and we’d often see his poster around, modelling clothes. He was going to call into the drop-in centre for us to audition him, but I was picked up by the police that day, for non-payment of fines, and I spent the weekend in Addington Prison. Butler turned up for the audition but it wasn’t on. He went out to a party instead and later that night he was killed in a car crash. We didn’t have a band name then and we decided to call ourselves Butler as a tribute to him."

Nicknames for some of the band members stuck. "Heidi was nickname of our other guitarist Matt Warren, and Angel and Hori were nicknames too, dating back to our Rotorua days," says Steve.

The natural musical talent of the newly minted band was soon audible. "Even the staff and social workers and the mostly middle-class pākehā volunteers there started to enjoy it," Steve recalled. "We started to get a following, and we’d play a concert there every Sunday night. Word of mouth spread and it was often packed. Quite a few students and general town people started coming. There were plenty of Polynesians and Māori in town, so we’d get invited to play at their parties and weddings sometimes too.”

The campus circuit

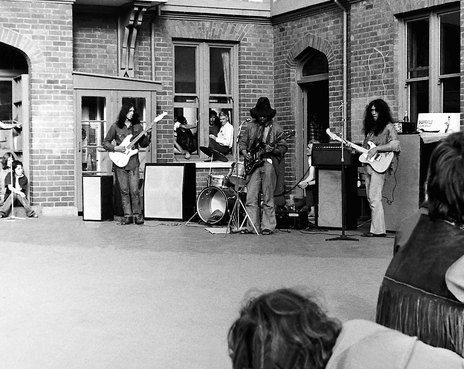

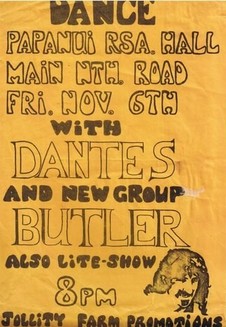

As a buzz around Butler built, the band was invited to play orientation week gigs at the University of Canterbury, starting in early 1971. I had just begun studies there, and I have fond memories of beer-soaked campus gigs featuring Butler serving up high-energy and more than competent cover versions of the songs we'd play in our frigid student flats.

Apirana recalls, "We built up a repertoire of covers early on. People loved Hendrix, Santana and Joe Cocker, stuff we liked too." A next step was to begin writing group originals. "I’d write some words that rhymed and the others chipped in," says Steve.

"I watched Howard Morrison sing with the Quartet, and I saw the reaction of the audience, all loving him. I thought, 'that's what I want'."

— Steve Apirana

One asset that helped Butler stand out was a warm sense of humour, something their peers often lacked. One website post remembers Steve introducing a Santana cover as a song "by Carlos and the Sultanas". Another post on the ProgNotFrog site recalls their Christchurch Town Hall gig supporting Osibisa: "When someone's guitar strings broke, the band left onstage started singing a song about 'blowing their big break' cause the guy broke his guitar strings."

The eclectic sound of Butler came naturally, Apirana explains. "Growing up in the 50s and 60s we all liked pop music, whatever was on the radio," says Apirana. "Howard Morrison was a big influence, 'cos he was from Rotorua." In a June 2013, Māori TV interview called Unsung Hero, Apirana expanded on this. "I watched Howard Morrison sing with the Quartet, and I saw the reaction of the audience, all loving him. I thought, 'that's what I want'."

"When I was 15 or 16 the psychedelic and hippie thing started so I got into people like The Lovin' Spoonful, Vanilla Fudge, and Donovan," says Apirana. "By the time we got to Christchurch, we had a head full of different stuff. Initially I thought blues was boring, all that 12 bar stuff, but from hanging around student flats then I heard more of it. I loved early Fleetwood Mac and John Mayall. I became a huge Peter Green fan, as a guitarist and singer. Then of course there was Hendrix, Santana, Jeff Beck, Clapton and Janis Joplin – all that blues-rock. I always loved vocal harmonies too, from The Beatles to The Four Seasons and early Bee Gees. It was more the cool stuff we’d play at gigs though. Another inspiration was a Māori band from Rotorua, Collision, and we rather modelled ourselves on them." Other New Zealand rock bands to have a big impact on the young Apirana included The Underdogs, The La De Da’s, and The Human Instinct with Māori guitar hero Billy TK.

Butler's career took a significant leap in 1972 when they took over from fellow blues-rockers Ticket in a residency at top Christchurch music club, Aubrey's. Apirana told Māori TV, "Ticket were like The Beatles to us. They were the number one band around. I'd go to see them whenever I could, getting tips from their compositions."

Regular playing at Aubrey's, support slots for visiting bands like Daddy Cool and other gigs in Christchurch and beyond helped Butler hone their skills, and they began asserting themselves as one of the best live bands in the country.

A Record Deal

This fast-growing reputation led to an invite to appear at the now-legendary Ngaruawahia Festival in early 1973, alongside such other fledgling New Zealand bands as Dragon and Split Enz. "Back then everyone was getting record deals," notes Apirana. "Our manager asked around for a deal and Pye took us up on it. They put us on a new label, Family. I think John Hanlon was the only other artist on it."

Initial high hopes would soon sour, however. "In June 1973 we went into Stebbings studio in Auckland to make our first album. It was a fantastic studio but we had a hard time with the producers and engineers. We were very green about the studio. We thought we’d just play live, but they wanted to record our parts separately. We were so used to playing together as a band that we got so disoriented by this. It was such an unpleasant experience."

Butler's disenchantment with the record and the label grew as time went by. "It took them 18 months to release it and by then we’d progressed more into prog rock and bands like Wishbone Ash. We weren’t even playing many of those songs on the record." An initial single had a cover of Creedence Clearwater Revival hit 'Green River' as the A-side, but it fared poorly. "The label never really got behind it," Apirana laments.

Nine group originals nestled alongside covers of 'Green River’, Cher's hit 'Bang Bang’ and the Four Tops classic 'Reach Out I’ll Be There'.

On the Butler album, nine group originals nestled alongside covers of 'Green River’, Cher's hit 'Bang Bang’ and the Four Tops classic 'Reach Out I’ll Be There'.

Despite the album's failure, Butler remained popular on the touring circuit, and they opened for such visiting groups as The Average White Band and Osibisa. "It was great to meet legends like that," he says.

The story behind the AWB slot is an interesting example of positive racial discrimination. "When Average White Band toured New Zealand in early 1975, they wanted a black band to open and they asked us. We did three gigs with them, Nelson, Mount Maunganui and Auckland. That was a great tour."

Apirana notes that, "Some of the media attention we got around the country was based on being all-Māori. We were proud of that identity and we did get some gigs because of that."

By 1976, Butler were hoping to make another album, one that better captured their improved musical chops, but internal and philosophical differences within the band deepened, causing them to call it quits in 1977.

A key factor here for Steve Apirana and Heidi Warren was their deepening faith, Apirana recalls. "By the end of 1976 we had new management and we’d bought a bus, but the timing was not so good. We became Christians and that had a big impact on Heidi and myself especially. We split when our bassist Angel decided he wanted to spend more time on his marriage and with his family. Both Heidi and I had been married and had children by then. After Angel‘s wife said he had to reassess things, we decided not to replace him. Heidi and I decided to explore the Christian music scene and make more of a commitment to Jesus."

The problems inherent in pursuing both their faith and a rock and roll life came into full focus when Butler was offered the support slot for a show by a musical hero, Joe Cocker. They reluctantly turned it down in as it conflicted with a bible study night and their friends Dragon stepped in.

Reflecting on their earlier rock and roll lifestyle, Steve Apirana now candidly expresses some regret. "We treated our wives like rubbish. We thought it’d all be fine when we bought them fur coats and flash cars!"

Steve is equally blunt in explaining why such material gains never came Butler's way. "We were a messy and undisciplined band. We were not a hungry band. We were unambitious in terms of working hard. We spent too much time trying to find drugs. I remember Dragon were rehearsing in Christchurch at one stage, so we thought we’d go over and hang out with them. They were like ‘sorry guys, we’re working'. This was in the middle of the day. They were working hard – they had plans. We just thought it’d come to us, so I guess we were arrogant then.”

Solo career

A long career as a solo artist in the Christian/gospel/blues music field has definitely taken Steve Apirana much further geographically than Butler did. Upon the demise of Butler, he became a social worker for the Anglican City Mission in Christchurch, a role that fittingly included work at the Open Door drop-in centre as well as running his own drop-in centre out of a caravan in Cathedral Square.

In 1981, Apirana formed The Velvettes, an entertaining rock and roll covers band that was popular on the New Zealand circuit over a decade-long career. Since then, he has performed primarily as a solo singer-songwriter. "I have been playing gospel music full-time professionally for 25 years," he says.

In 1992, Apirana moved to Noosa, Queensland, with his second wife Ainsley. They have three children together and three from earlier marriages, and they frequently perform together, as the duo Steve and Ainsley and as members of the rootsy Dirt Floor Alliance. "As Steve and Ainsley, it is a more laidback style of music," he says. "It is often about our relationship, Māori and Pākehā, Kiwi and Australian. It is about reconciliation, from a spiritual point of view. I had a rugged upbringing, and had cultural issues to sort out, but it is working for us. We're in quite a cruisy position, socially and spiritually."

They have often been cited on international music websites dedicated to the psych/prog sounds of the 1970s.

Apirana has toured Australia extensively, played in England (including appearances at the major Greenbelt Festival), the USA, and Europe, and released a number of solo albums. He has a home recording studio and has produced albums by other Australian gospel artists.

He frequently returns to New Zealand to tour (often with his wife), at both church and public concerts and festivals (including Parachute). In 2013, for instance, he toured NZ in July and August, then November, performing at maraes, RSAs, churches, festivals, conferences, colleges, and house concerts

"I do still love music. I am more laidback and less ambitious about it now," he says. "Now it is about meeting people and having them enjoy it. I'm writing music that has a wholesome message. I got more into the social part of life, communicating with people and trying to be a solid father to my kids." The Māori TV interview [Unsung Hero on Native Affairs] termed him "one of New Zealand's iconic Christian artists."

Angel Adams also now lives on the Gold Coast and works as a landscaper. Heidi (Matthew) Warren lives in Rotorua, while Hori Sinnott died in 2012.

The only record they ever made is not one they're proud of, but Butler has not been forgotten. Those who caught their always-entertaining gigs around the country retain fond memories, while they have often been cited on international music websites dedicated to the psychedelic/prog sounds of the 1970s.

Looking back on their legacy, Steve Apirana observes, "Butler has become more of a myth than anything. People swear they saw us play at such and such a gig, I know we were never at. It is hard to live up to that myth."

The same drop-in centre scene that spawned Butler also featured some other musical talents. "There were plenty of potential musicians in our crowd," says Steve Apirana. "Other bands started from that scene. One featured Tama Renata [later of Herbs] who wrote the instrumental theme for Once Were Warriors and the father of Scribe was in one too."

One post-Butler musical collaboration in the 1980s saw Steve and Heidi co-write the theme song to My Friends Are Dying, a film by controversial New Zealand-born evangelist Ray Comfort.

Steve Apirana - guitar, vocals

Heidi Warren - guitar, vocals

Angel Adams - bass

Hori Sinnott - drums

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air