It wasn’t that we never fell under the spell of the genre. In the early 1970s, albums by progressive rock titans like Emerson, Lake & Palmer and Yes sold like hotcakes, and Jethro Tull performed here to wide acclaim. Classical music critic William Dart could even be found extolling the virtues of the 1972 Yes album Close To The Edge in the pages of The NZ Listener, promoting it as a brave new music that finally legitimised rock as something for serious contemplation.

Running a progressive rock ensemble was seriously expensive.

No, we loved the impossible time signatures, 20 minute epics, sword and sorcery lyrics and massed banks of squealing synthesisers as much as any nation on earth, and remember, that’s heaps: in 1971, Jethro Tull was the second most popular touring act in America, trounced only by The Rolling Stones, and for a brief period in 1973, EL&P were judged the most popular rock band on earth.

It’s just that homegrown examples were almost as rare as hens’ teeth. And it wasn’t that we had the good taste to avoid the more extravagant pomp and excess of progressive rock, it just came down to sheer economics. Running a progressive rock ensemble was seriously expensive, with the necessity to purchase and maintain cutting edge technology (banks of synthesisers) and tour with massive PA systems. That was never going to work in NZ, and there was the small but prescient fact that electronic gear would be taxed heavily at customs.

Unlike England, few of our underground rock groups had evolved from psychedelia through to prog: mere hints of the genre are to be found on the first two Dragon albums, and in the jazz-rock fusion of Living Force. Then there’s the still awe-inspiring Split Enz debut, Mental Notes, which draws from early Genesis and the dystopian Mellotrontopia of King Crimson’s In The Court Of The Crimson King as much as it vibes off the art end of glam via Roxy Music. Others like Schtung and Think would have their moments too, but none matched Ragnarok in the prog stakes.

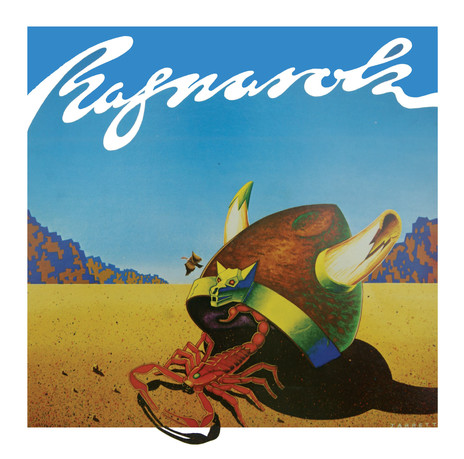

Still undervalued in the 2000s, Ragnarok have never seen their records properly reissued, and there’s no sign of any imminent revival. But listening to those two albums today, they’re phenomenal examples of their genre, a kind of space-rock hybrid with a bit of Hawkwind’s groove mantra, loads of mind-expanding psychedelics, surging Mellotrons, and mystical Norse mythology peppering their lyrics.

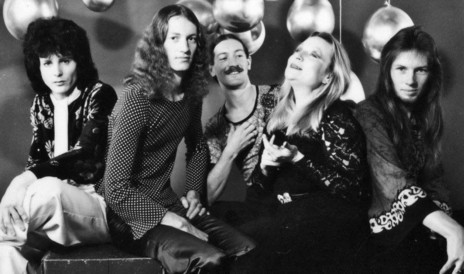

The debut album, released through Revolution, an independent label distributed by Pye, featured brothers Mark and Andre Jayet (drums and keyboards respectively), Ross Muir (bass), Ramon York (vocals, guitar) with the addition of singer-songwriter Lea Maalfrid. She brought a striking, impassioned and almost operatic flavour to the group that was a great contrast to the heaving Mellotrons, buzzing synthesisers and echoing psychedelia of the instruments. It’s one of the most unique albums released in NZ in the 1970s, and the hypnotic and very physical, almost funky at times, bass and drum work still sounds riveting.

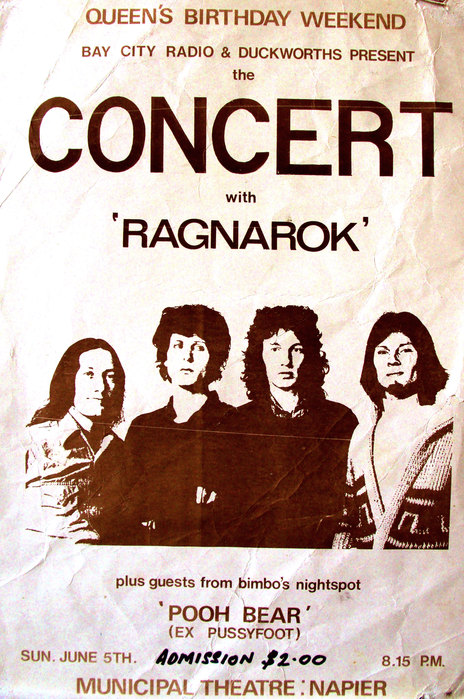

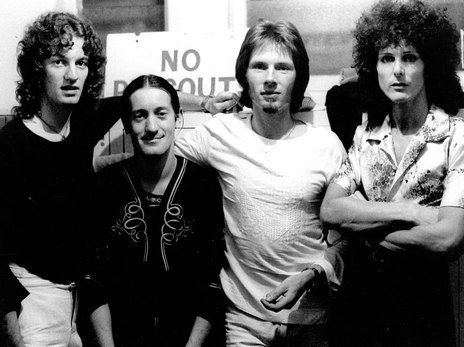

By the time of Nooks, released through Polydor, Maalfrid had taken off to England, where she ended up writing hit songs for the likes of Sheena Easton and Bonnie Raitt, so it was down to a four-piece, now based in Napier. Though not as pummelling, psychedelic or consistent as its predecessor, Nooks has its own charm, with more space given to the textures of instruments which, let’s face it, were seldom heard on NZ stages: it’s buzzing with a variety of synthesisers, guitar synthesisers, the aforesaid Mellotron and a variety of percussion effects.

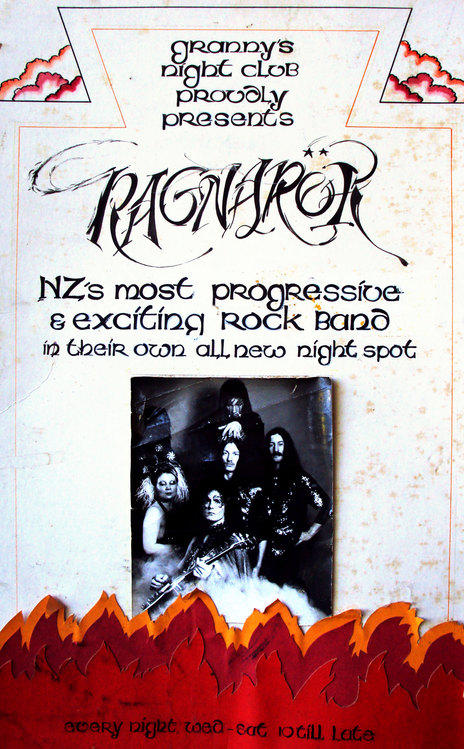

The group started out well, with a popular residency at Tommy Adderley’s Granny’s club.

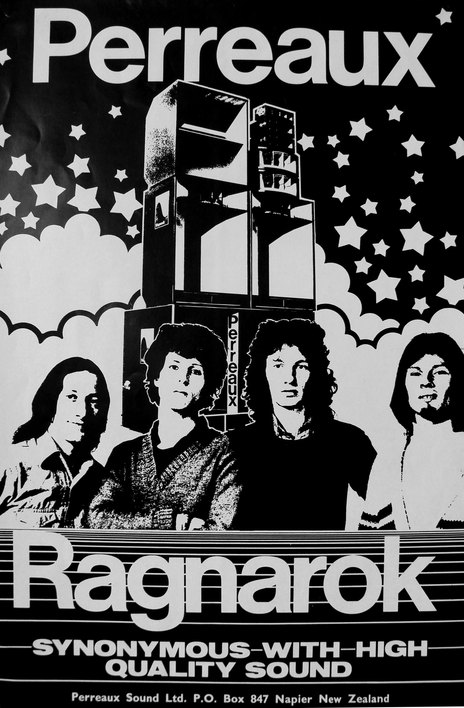

The group, who launched a financially disastrous national tour of theatres around Nooks, was a wonder to witness live, especially in the last years with their huge, exceptionally good (for the era) PA that had been assembled by Peter Perreaux of highly regarded hi-fi company Perreaux. But it was that combo of hi-tech instrumentation and gear that Andre Jayet blames on the group’s early demise. As he writes on the liner notes of a limited edition CD-R of live material: “And no thanks to ‘Piggy’ Muldoon who deemed that band equipment was not tax deductible. Our investment became a millstone which facilitated in the demise, not only of Ragnarok, but many businesses in the music industry.”

The group started out so promisingly, with a popular residency at Tommy Adderley’s Granny’s club, and they were just as popular a drawcard at the “Buck-a-Head” concerts as Dragon and Split Enz. Touring extensively from 1975, they proved a top earner, perhaps giving them the misguided determination to invest in the expensive technology that ended up killing them off.

Ragnarok’s genesis (so to speak) was in Christchurch band Flying Wild, which started in 1965 and featured Muir and the Jayet brothers. Later in the 60s they recorded for the Robbins label before relocating to Auckland. They seem to be the first group to have free and unlimited recording time at Stebbing’s then-new Jervois Rd studio.

After the break up of Flying Wild, Andre Jayet and Ross Muir played with the group Sweet Feat and eventually recruited Mark Jayet and Ramon York to form Ragnarok. Lea Wyber – later known as Lea Maalfrid – joined as vocalist. Her husband Tony, she said, “was the inspiration behind the name and the Nordic theme of the group. We were all friends and Tony Fernandez of Revolution Records was included in that group. Just prior to joining I worked with the wonderful Mr Billy Farnell at the La Boheme cabaret in Auckland singing jazz standards.”

Like most New Zealand bands of the era, part of each set consisted of covers, and Ragnarok staples were the likes of Led Zeppelin (‘Kashmir’), Pink Floyd (‘Have A Cigar’, ‘Wish You Were Here’) and uh … Peter Frampton (‘Do You Feel Like I Do’). Visually, they looked like hippies dressed up in drag, with long hair, makeup and shiny glam costumes (created by David Hartnell and Kevin Berkahn). The meat was the group’s own compositions, however. The show featured the requisite billowing dry ice, and yes, even a long drum solo.

By 1975, the tide was already turning on progressive rock overseas.

With the original tapes thought long lost, and no one offering to fund a careful mastering from vinyl, Ragnarok and Nooks have never been reissued, apart from “grey area” issues of Nooks in Japan in the mid-90s, and a mysterious 2008 US release combining Ragnarok with a live performance from 1976 (including an 18-minute version of Pink Floyd’s ‘Us And Them’).

In 2011, Andre Jayet transferred versions of both studio albums from hissy reel-to-reel and offered these as CD-Rs by mail order. One track, damaged on the reel-to-reel, is even missing from Nooks. Of more interest, perhaps, is the previously unreleased The Live Recordings, comprising desk recordings from gigs performed between 1976 and 1978.

Perhaps it was inevitable that Ragnarok’s story wouldn’t be a long one. By 1975, when their debut album appeared, the tide was already turning on progressive rock in England and America (although it simmered on in Europe for decades), and stripped-back hard-edged punk-flecked records like Patti Smith’s Horses were already starting to appear. By 1976, Auckland audiences apparently thought them passé, hence their eventual withdrawal to the provinces, where some level of acceptance was a given.

But in the post-everything environment of the second decade of the 2000s, even progressive rock has been largely forgiven its indiscretions, and given a decent release, those two Ragnarok albums might just find a whole new audience to love them.