AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Dick Frizzell

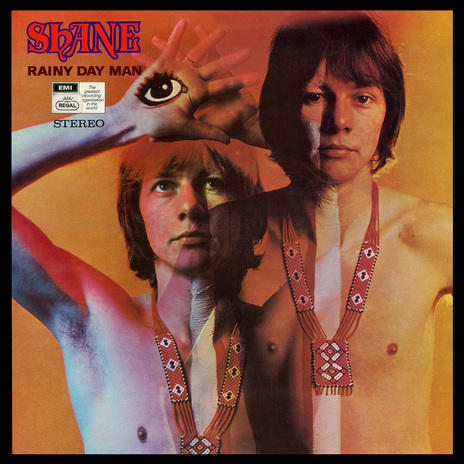

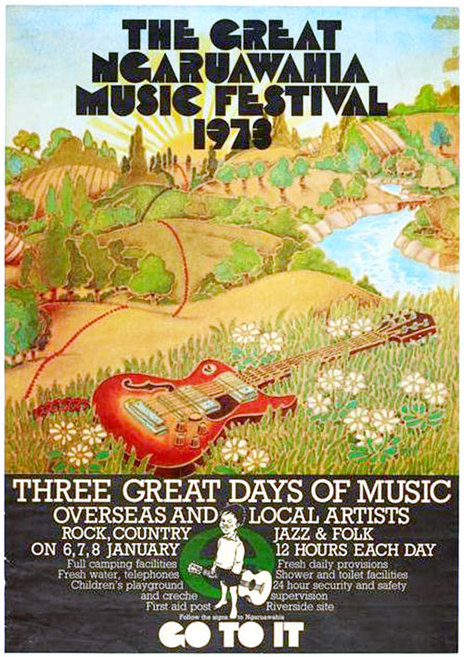

He designed posters for Radio Hauraki concerts and the Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival, covers for local bands Human Instinct, Ticket and Dragon and was called in to tone down David Bowie’s Hunky Dory cover for record executives who thought he was too outrageous and likely to be a one hit wonder.

Frizzell messed with the hei-tiki, delivering cubist and art deco versions and gave Charlie the Four Square man several decades of makeovers, most recently with a guitar slung over his shoulder on the cover of the Great New Zealand Songbook.

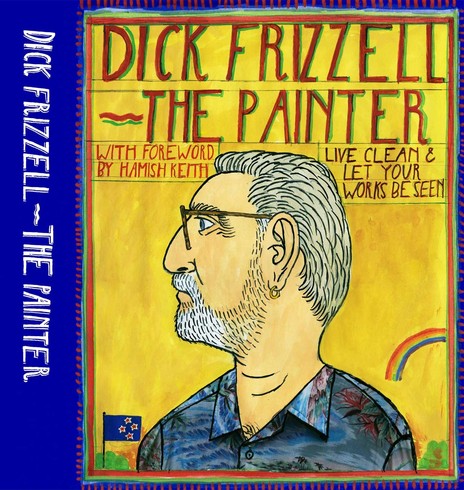

The body of his work so far features in a coffee table book, Dick Frizzell the Painter, laid out in collaboration with eclectic New Zealand artist-musician Fane Flaws.

For a fleeting moment music might have supplanted art as a priority for Frizzell.

For a fleeting moment music might have supplanted art as a priority for Frizzell until a reality check about uncertain income and playing in dusty nightclubs hit home.

He had purchased a bass guitar, taken lessons from top jazz and session player Kevin Haines, learned all the funky Sly & the Family Stone riffs and reckoned he was getting pretty good until he adjusted his trajectory toward art school.

On his return from three years at Ilam School of Fine Arts at University of Canterbury in 1964 he and his young family headed to Auckland where he took a major about turn and joined the advertising industry.

Vulgar and exciting

Frizzell quickly became part of an in-crowd hungry to devour the latest international cultural influences.

“It has been my good fortune to have been right there during interesting moments in our pop cultural history. It was inevitable that I would get involved in something as vulgar and exciting as advertising.”

Rock and roll was exploding out at the same time. “It was one big, mad, exciting, drunken, drugged sort of thing ... very colourful.”

Part of the fun was the number of clients who seemed to have endless budgets to sell product, giving commercial artists like himself pretty much a free rein. “There was no market research or anything in those days.”

“Because of my interest in music you were always hanging around the record stores, like Taste in Lorne Street where the guys behind the counter would play you the latest Elton John or King Crimson.”

In record stores Frizzell would often meet up with record company executives, who would ask him to design a poster or a record cover.

Bowie’s a tosser

He recalls Pye boss Tim Murdoch asking him to come in and view the cover for the local release of David Bowie’s Hunky Dory album. “He said ‘this guy’s a complete tosser, the record cover’s a disaster, he’s all covered in make-up and we can’t release the album with all this full colour, drag queen stuff’.”

He wanted something in one colour so Frizzell simply used the back cover, a sepia image of Bowie in bellbottoms with the song titles panned around the image and that became the New Zealand cover.

Every colour meant additional printing plates and cost and that kind of skimping on cover art went on all the time, says Frizzell, who had regular requests to adapt or simplify, preferably using only one or two colours to save cost.

Typically they were printed on light cardboard with ugly outside folds; only rarely would they do a gatefold. “They’d throw away half and do one sleeve and then paste the edge over the top rather than the inside so you had a horrible seam.”

Frizzell was always keen to have the original cover art for his personal albums and he and his friends would try and have aircrew bring the original covers back from the US or UK.

For example the “beautiful big fold out” of the Doors Waiting For The Sun or the Bob Marley cover of Catch A Fire shaped as an open-out Zippo cigarette lighter with Marley smoking a doobie. “We didn’t do that, we just photographed the whole thing when it was shut.”

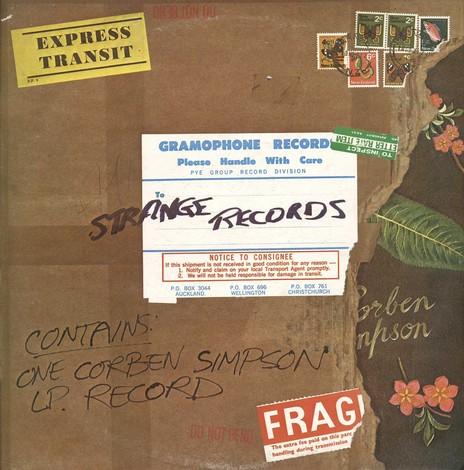

He was called on to create the cover art for Corben Simpson’s self-titled first solo album with Bruno Lawrence on drums, Alan Moon on keys and Tony Littlejohn on bass. “Because Corben is such a strange man I had real difficulty coming up with an image that worked for that crazy album.”

In the end he says he got desperate and opted to make it look like registered package in cardboard that had come in from England. “I had it franked at the NZ Post Office, had string tied around it and then ripped one corner off which showed what the album inside might have looked like.”

Conceptually, he says “it was a great cover” and one of the album projects he most enjoyed working on.

That’s the Ticket

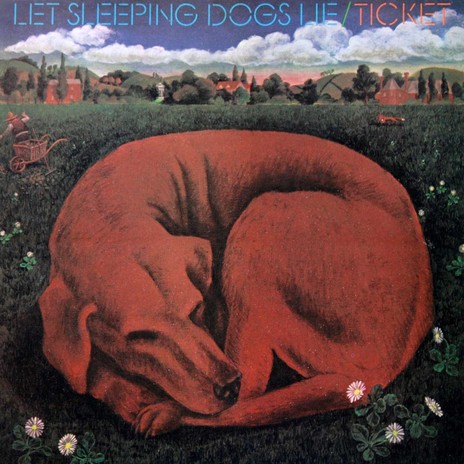

Ticket, a powerhouse of guitar driven original New Zealand prog-rock, featuring Eddie Hansen on guitar, Ricky Ball on drums, Paul Woolright on bass and Trevor Tombleson on percussion and vocals, called on Frizzell to design the cover for their second album and final album, Let Sleeping Dogs Lie.

“I suggested a dog lying on the grass and they went for it. I made it look close to a painting which was about the closest I got to a full on Frizzell image. You’d always get to meet the band at some point ... exotic creatures they were,” he laughs.

Frizzell says he was always an American guitar band fan and loved good use of the wah wah pedal. “A complete guitar lead break nutcase ... The Doors, Canned Heat, Country Joe and the Fish ... Grateful Dead.”

Among the soundtracks to his late night life working on advertising or other art projects was Grateful Dead’s Anthem of the Sun. “I used to listen to it down really low so as not to wake the wife and kids ... and I’d ring up friends and hold the phone close to the speakers and say, ‘hey listen to this’.”

He admits he never purchased much local music back in the day. “Money was tight. Let’s be honest, if you had a choice between Grateful Dead or Human Instinct … you couldn’t afford both.”

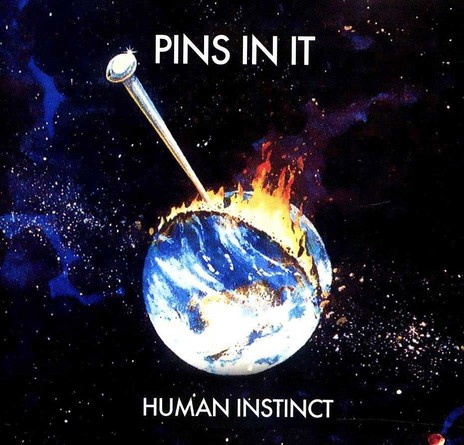

Planetary pin cushion

Dick did get the invitation to design the cover of the third album from The Human Instinct, featuring at the time Billy TK on guitar, Neil Edwards on bass and Maurice Greer on drums.

Frizzell and his friends liked the band not only for the searing guitar work but because they seemed “like the real thing”. Band leader Greer put forward the idea of Planet Earth with a pin stuck in it.

“I used acrylic paints and did a lot of research into design techniques that were happening overseas at the time.”

Frizzell was excited at the album cover art, animation and books that were being produced at the time, including Alan Aldridge’s Beatles Illustrated Lyrics and the animation of Yellow Submarine. “There was so much that was new happening in the world ... art didn’t matter ... it was always like what’s next.”

The Haight Ashbury psychedelic explosion led to the idea of making large posters “you can’t read”.

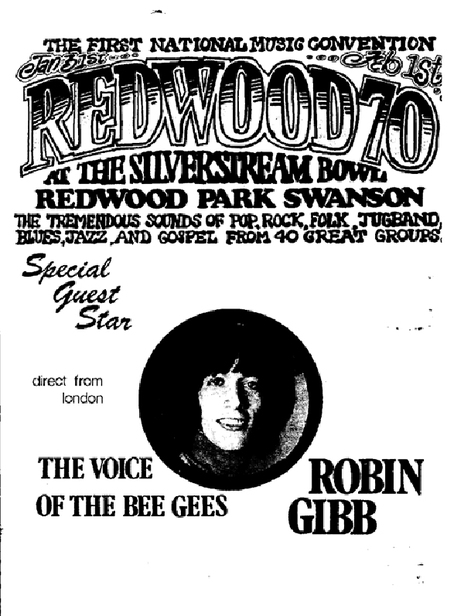

The Haight Ashbury psychedelic explosion led to the idea of making large posters “you can’t read”. He chuckles and repeats the sentence, “That was a great idea, let’s make a cover you can’t read ... next thing Phil Warren is running a big music festival at Swanson [Redwood 70] and wants ‘a big Fillmore East poster’ so you’d go away and whip this thing up with oodles of information on it.”

Being asked to produce the poster for The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival was another challenge that certainly wasn’t going to be delivered “with minimalist Helvetica flush left design.”

The memorable poster for the big outdoor event organised by “big Robert Raymond and little Barry Coburn ... a kind of good cop, bad cop duo” featured a “little Māori boy against the Greenpeace logo,” which Frizzell says was adapted from a sketch by World War II artist and landscape painter Peter McIntyre.

“Only a fine artist working as a commercial artist would be able to make those links which I think probably underscore a lot of my work and my parallel life as a studier of art.”

Robotic duck wanted

Frizzell recalls a visit from Marc and Todd Hunter and the boys from Dragon while working at Bob Harvey’s advertising agency. Future keyboard player Paul Hewson would also often drop by in his school uniform to hang out and draw.

“He was quite conservative and didn’t like ‘all that modern art rubbish’. He used to have me on about why I was doing all this cubism, modernism and pop or anything that wasn’t representational or straight realism, when I was so talented.”

Ironically when the Hunters and their band mates, “these tall Westie boys in their leathers”, came to discuss a cover for their album Universal Radio they wanted “a robot that looked like a duck which they had seen somewhere and a weird finger of doom with static electricity pointing to the sky.”

Another “static electricity, cubey, horned devil thing” was later completed for the band Ragnarok.

Designing record covers for K-Tel compilations remained Frizzell’s dark secret for many years; jewellery boxes with baubles tumbling out in lurid pink and teal colours with Tony Orlando and Dawn and other artist names written in them. “It was all pre-computer, Rotaring drawing pens and compasses ... I tell you it wasn’t easy being cheesy.”

Being involved in animation at a critical time in the evolution of both advertising and television saw Dick involved in the creation of some warm and friendly two dimensional characters whose initial purpose was to sell ice-creams, cheese or peanuts … many of them fixed themselves firmly in the New Zealand psyche, later becoming pop-art Kiwiana

He still likes all those “logo boys”, Eskimo Pie man, Eta Peanut guy, Four Square Man, Frosty Boy, Ches n Dale ...

Intensely New Zealand focus

Dick Frizzell headed to New York to expand his horizons and work for a time but was encouraged by mentors to head back home and paint things that were uniquely New Zealand.

To many people, that might have meant landscapes, buildings and indigenous or colonial imagery, but he saw the challenge quite literally.

“I never wanted to be anything but a New Zealand artist in New Zealand and so I approached a lawnmower the same way I would look at a sunset with the same intensity as a landscape.”

Frizzell says he has a non-hierarchical overview. “I think it’s a sort of Asperger’s thing sometimes ... to me everything’s got a story.”

His controversial lithograph Mickey to Tiki, a cartoon Mickey Mouse morphing in stages into a Māori hei-tiki is considered one of the best-selling New Zealand prints. The original sold in mid-2013 for $94,000.

Early in 2009, Dick was asked to contribute to the Great Kiwi Songbook, a double CD compiled by former record company executive and marketer Murray Thom. At first the brief involved “some Kiwi scenes” but that was before Thom woke up to Frizzell’s long association with the music industry.

He saw his collection of Radio Hauraki posters and the next thing you know Charlie the iconic Four Square man had a Fender Strat slapped over his shoulder for the front cover and on the back. “No one’s ever seen the back of the Four-Square man before.”

The works of Frizzell, now part of the cultural establishment he once challenged, are in demand at home and abroad. Instead of creating brands for others as he did in the advertising industry, he and his wife Jude manage and market his own brand which includes a wine label.

Compiling the past

In a 2009 interview for Radio New Zealand’s Musical Chairs programme Frizzell was reflecting on the eclectic collection of images that make up his life’s work … cubism, realism, surrealism, canvas convergences of the sacred and the secular, the symbolic and the literal, all mixed up with advertising copy, concert posters and record covers.

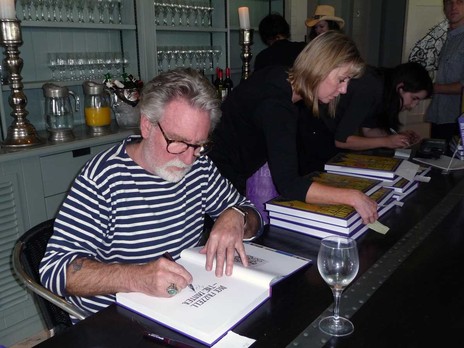

The result? A glossy coffee table book interspersed with photographs and his life story, Dick Frizzell, the Painter (Random House, 2009).

“I’ve just treated it like an illustrated autobiography really … Hamish Keith was going to write it and I kept providing bullet points that kept joining up so I thought why don’t I do it. I can string a sentence together ... longhand ... and so I kept going and had so much fun.”

Hamish wrote the introduction “because he knows me best” and Fane Flaws did the layout. “He’s out there and took me beyond myself. I had to keep a close eye on him but I thought ‘C’mon Dick just get over yourself and go with it’.”

Flaws wanted the book to pull in everything; commercial work, advertising, fine art. “The only thing I didn’t put in were those K-Tel covers,” he laughs.

In 2012, Frizzell completed a series of paintings based on the poems of his friend Sam Hunt, first exhibited on 7 February 2012, and was quoted in the Dominion Post as saying he and Hunt in their respective poems and paintings had committed the ultimate sin: the “sin of being understood”.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air