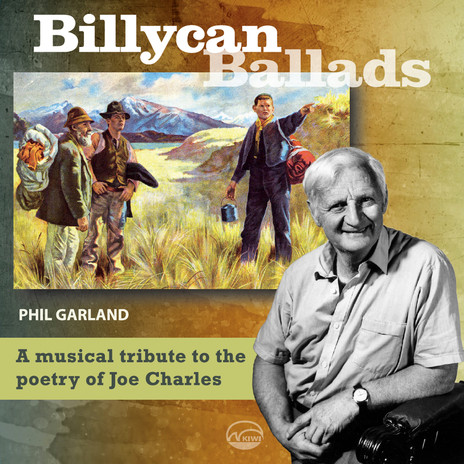

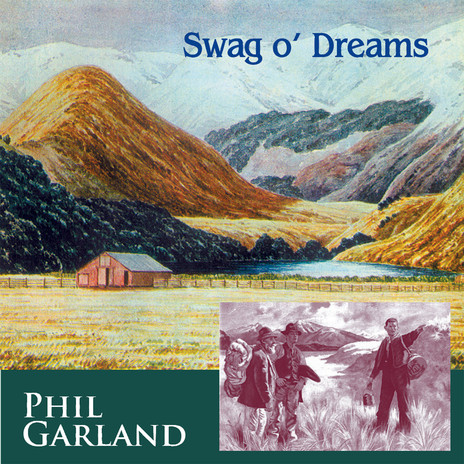

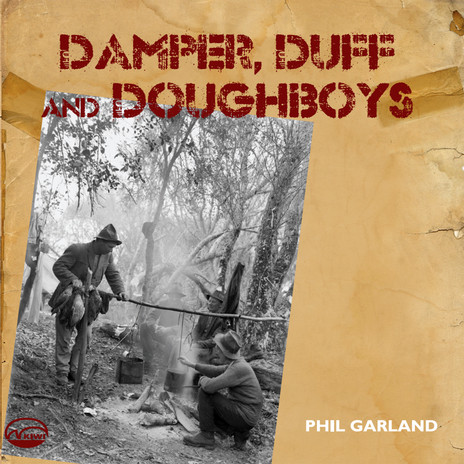

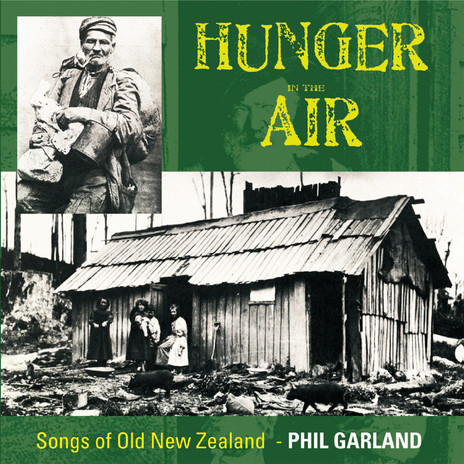

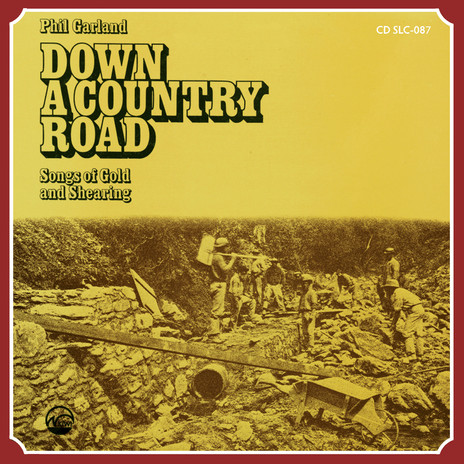

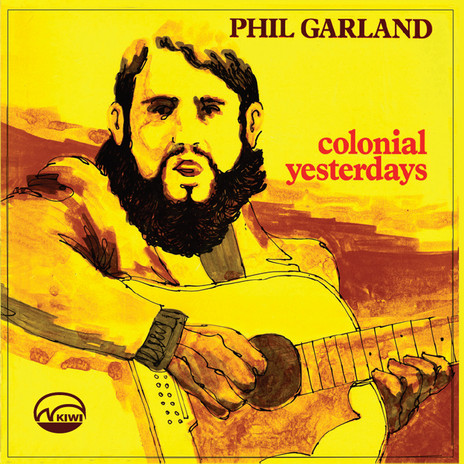

Over 50 years, Garland recorded 19 albums of New Zealand balladry that told stories of the “folk” of this land from the early European-settler days; of the pleasures and difficulties of our wild geography and the people and events that continue to shape this nation.

The arts, in all their multifarious forms, hold a mirror up to society. Pictures and stories, plays and drama, myth and allegory, poetry and song: all of these reveal different aspects of a people. They reflect who we are, how our culture operates, and how what we do affects others.

Alongside the storytellers, authors and historians, Garland sang to us and about us.

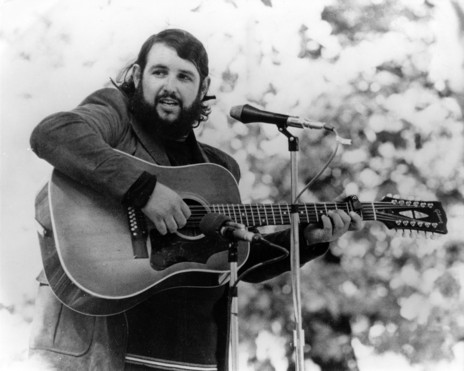

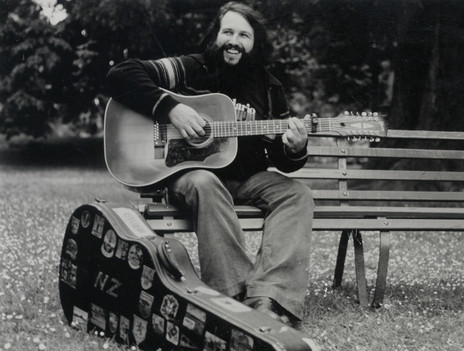

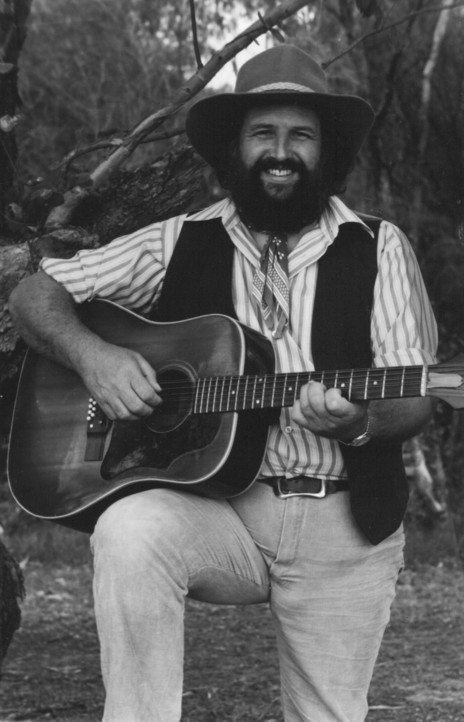

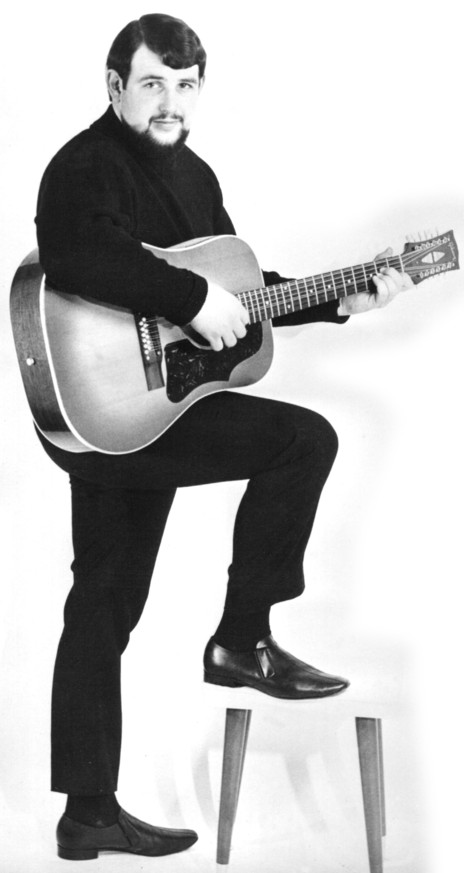

Alongside the storytellers, authors and historians, Garland sang to us and about us in tunes and verse; one man with resonant voice and 12 deftly plucked guitar strings. He sang of the Dalmatian gum diggers of Northland, the coal miners of the West Coast and the gold-miners of Central; of the swaggers and scoundrels, the pioneers and moonshiners; of the snow-crested high-country peaks, Canterbury nor’westers and the wind in the tussock; of the hardship of panning for gold in snowy Tuapeka, the notorious Rising Sun Hotel in Cathedral Square, and of the young New Zealanders who died fighting wars on foreign soil.

Garland liked to tell stories and sing songs about interesting things in the days of old that have long since disappeared. His song of Christchurch, ‘Age of Grace’, is a wordscape of the innocent, pre-quake days of his own youth and childhood when characters like the Milko, the Dandy, Ice-Cream Charlie, the Rag’n’Bone man and the Bottle-o were regulars around town. And in the ongoing folk tradition, if he didn’t have his own words he would set poems he had collected to music, or adapt and arrange what went before, for example, replacing Australian allusions, descriptions and place names for those from New Zealand.

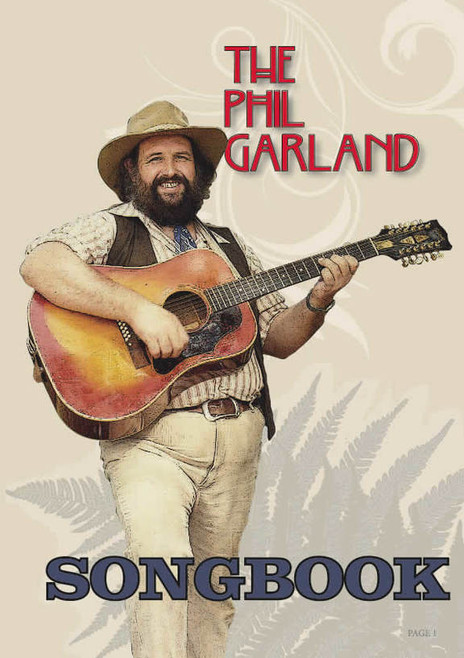

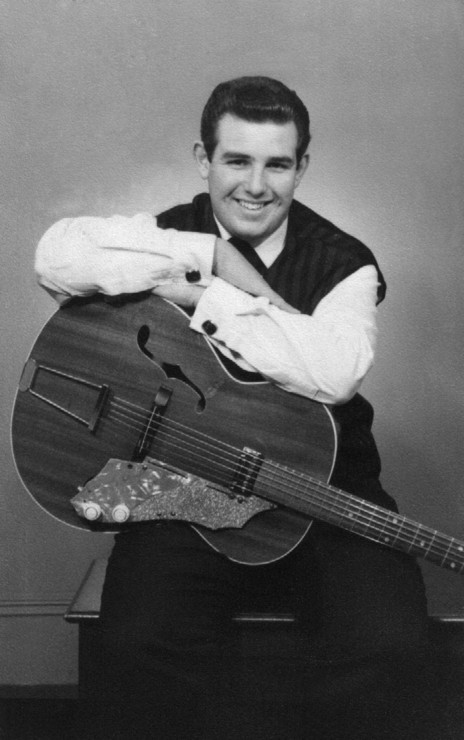

The nature of the musical gift is that it taps you on the shoulder and won’t let go. It picked Garland when he was a child and gave him a good ear for a tune. Later he made the finals of a school talent quest and when the bug really bit, aged 16, with Bill Haley and The Comets revving up the radio waves, he sold his stamp collection and bought his first guitar.

Back then, American crooners with slicked-back teddy boy quiffs were rocking around the clock or singing their baby back home, and British skiffle artist Lonnie Donegan was plying a jumpy line between trad jazz and the rhythmic, driving folk of such imposing forerunners as Lead Belly.

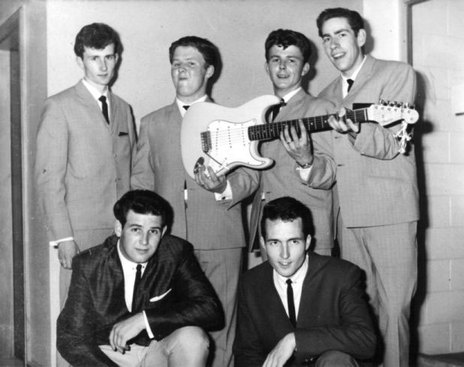

Garland was in several prominent Christchurch groups in the early 1960s, including his former school band Phil Garland and the Fortunes, the Saints, the Dynamics, and the Playboys, which he founded with stylish girl singer, his then-girlfriend Diane Jacobs (aka Dinah Lee).

Of those days, he later wrote: “Diane and I became a couple and supported each other’s musical ideas. Dad used to transport us to and from performances, never uttering a word against what I was doing.”

Before going their own ways, Garland and Jacobs headed to Auckland in April 1963 to try their luck in showbiz. While there, Garland recorded the song ‘Little Band of Gold’ for Viking Records, whose A&R man Ron Dalton had heard him singing with the Playboys at the Top 20 Niteclub in Durham Lane. The song topped the Coca-Cola Hit Parade.

By the mid-60s, popular music was at the crossroads. Electric rock and pop were heading in one direction and the acoustic folk scene had taken off in another with its own myriad styles, from centuries-old minstrel tunes and ethnic folksong to original narrative ballads, field hollers, and colonial bush songs.

The 200,000-strong March on Washington DC in 1963 for jobs and freedom attracted worldwide attention to civil rights for the oppressed and gave voice to the plangent African-based gospel and other powerful protest songs rooted in the black vocal tradition. The anti-Vietnam War and anti-nuclear movements spawned their own protest songs sung by scruffy individuals, earnest wailers, or pristine college vocal groups; all of these sounds were fresh and appealing against be-my-baby pop, with their messages going out loud and clear through 45s, top-20 lists and the international reach of television.

By 1964, Garland developed a strong interest in folk music and it soon became his abiding passion and totally absorbing lifestyle. The following year he travelled to Britain and Europe with the few New Zealand songs he knew, and while there heard the whole gamut of folk styles. This experience encouraged him to further his knowledge of New Zealand’s heritage, and he became convinced of two things: his hometown Christchurch needed its own folk music club, and he needed to travel around the country to collect as much rich historic material as he could before it was lost forever.

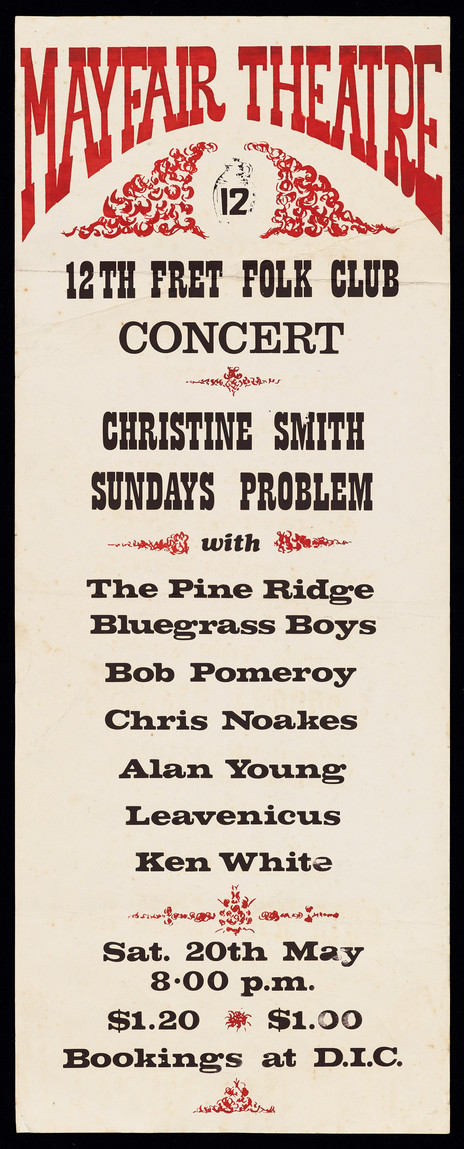

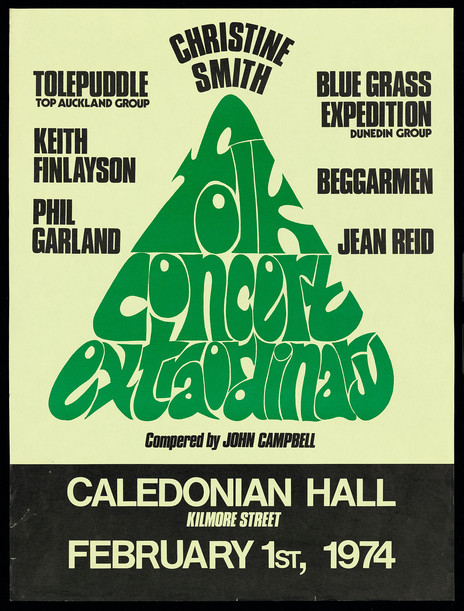

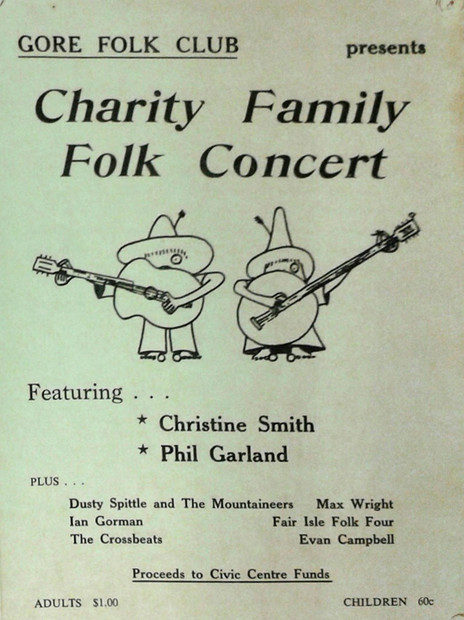

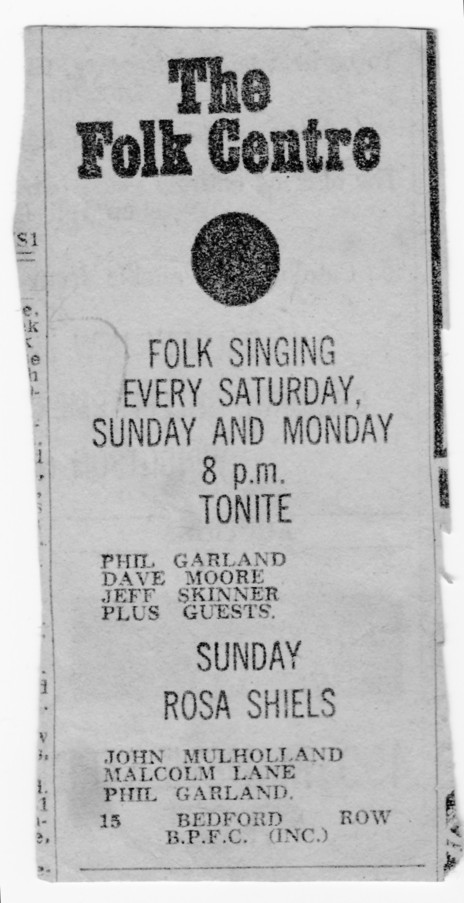

In 1967 he formed the Christchurch Folk Club (incorporated as the Banks Peninsula Folk Club) and set up its first venue as the Christchurch Folk Centre. By then there were various coffee bars around town that were happy to have musos on stools in the corner, but it was the rich interchange between the University of Canterbury Folk Music Club, with its strong membership and regular concerts, and Garland’s Folk Centre that resulted in them becoming the default venues for folk music in Christchurch.

For the next eight years, while Garland and then-wife Libby hosted, the Folk Centre in its various locations would be chocka on opening nights, especially weekends. Local performers would share the bill with guest artists from Australia, Britain, the US and Canada, and the backroom resonated with musical banter in many different accents and the tuning twangs of guitars, banjos, violins, mandolins, dulcimers and so on.

Garland performED songs from his catalogue of Kiwiana, or maybe blowing the jug with the Band of Hope Jug Band.

Audiences saw Garland playing solo, performing songs from his rapidly growing catalogue of Kiwiana, or maybe blowing the jug with the Band of Hope Jug Band alongside the likes of graphic artist Chris Grosz, Warwick Brock, Bill Hammond (the renowned visual artist) on washboard, Robin “Dobbin” Elliot and Gordon Collier, and many others.

Other nights Garland would step aside for performers from north and south, such as Christine Smith, Jae Renaut, Hugh Canard, Neill Pickard (later founder of the Christchurch Polytechnic Jazz School), Serenity, Annie Whittle, Val Murphy, Tony Brittenden, Bernie Cherry, the Stoney Lonesomes, Max Winnie, John Hayday, Phil Calder, Dave Hart, Geoff Skinner, Paul Metsers, and many others.

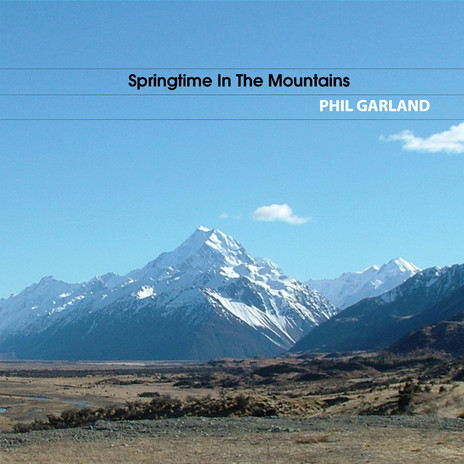

Garland began touring regularly, singing New Zealand’s stories to audiences far and wide. Plaudits started rolling in. Rotary International recognised his work with an award in 1971 and two of his songs were chosen to represent the country in the United Nations Songbook. Out of 60 entries, his 1977 Radio New Zealand music documentary, ‘Landfall New Zealand’, won a prestigious Japanese award. In 1981 Garland was invited to sing New Zealand songs on an America-wide television broadcast. Garland’s Springtime in the Mountains won the Folk Album of the Year Award at the New Zealand Music Awards in 1984; two years later Send the Boats Away – an album to which he contributed – won the same award.

Moving to Australia in the late 1980s, Garland gained immediate acclaim for his performances and recordings. From his Armadale base in West Australia, he played the Australian folk circuit and, with his band Bush Telegraph, made another two albums, garnering an award from the Armadale Council for his contributions to the WA music scene and a description in the West Australian newspaper as “cultural wealth from New Zealand”.

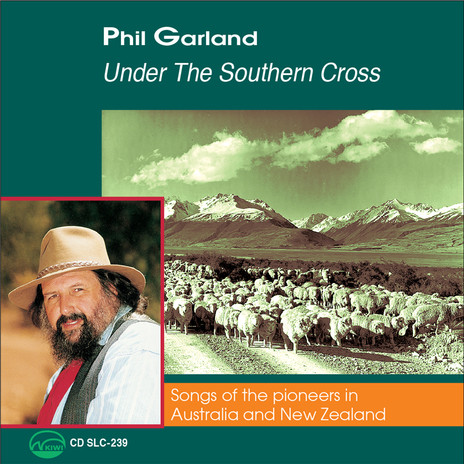

He celebrated his return to New Zealand in 1996 with the compilation album Under the Southern Cross and with the release of his Australian-published songbook, The Singing Kiwi. It featured 120 of the songs he had collected over the previous 30 years.

Garland was inducted into ROCKONZ – the Christchurch Rock and Roll Hall of Fame – in 2007 and, in the same year, again won the best folk album at the New Zealand Music Awards for Southern Odyssey.

In 2009 he published his major opus, a book called Faces in the Firelight: New Zealand Folksong & Story (Steele Roberts), a compendium of songs, poetry, yarns, rhymes and tall tales. The includes profiles of the people he encountered during his song-collecting expeditions, combined with material he gathered and from the New Zealand Folklore Society archives. Faces in the Firelight allows us to look deeper into the colourful fabric of New Zealand, its people and their ways. Flick through the pages and little gems jump out, such as this rhyme that Garland said kept cropping up in the South Island high country:

With a little bit of sugar and a little bit of tea,

A little bit of flour you can hardly see.

With hardly any meat between you and me,

It’s a bugger of a life, by Jesus.

Although that ditty might have originated in Australia, Garland gives it a New Zealand spin in another version:

Where the keas call and the trees grow tall

And there’s very little to please us.

It’s here I’ve to stay till the end of May

What a hell of a place, by Jesus.

For 50 years Garland performed solo in clubs, festivals and schools throughout Australia and New Zealand; at ceilidhs or in concert with several rollicking bush and country bands, such as the Woolly Daggs Bush Band, Shagroon, the Canterbury Crutchings Bush & Ceilidh Band, and the Bush Telegraph. He has run musical history and folklore workshops at clubs, festivals, universities and conferences in Australia and New Zealand. He researched and wrote for Southland tourism and Radio New Zealand, taught music, appeared on radio and television, composed and recorded his own songs, and set bush ballads to music. His songs have been covered by solo artists and bands in New Zealand, Australia, the US and Canada, and the folk music club that he started in Christchurch back in 1967 continues to this very day.

Garland’s lifetime mission was to collect and preserve our heritage, verbal or written, in prose or in song, and his work speaks for itself and his achievements. In 2014, he was awarded a Queen’s Service Medal (QSM) in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List for services to New Zealand folk music.

“As an interpreter of New Zealand’s folk and country heritage, Phil Garland is without peer,” wrote the Press a few years ago. “He must surely have a reasonable case for being regarded as a National Living Treasure.”

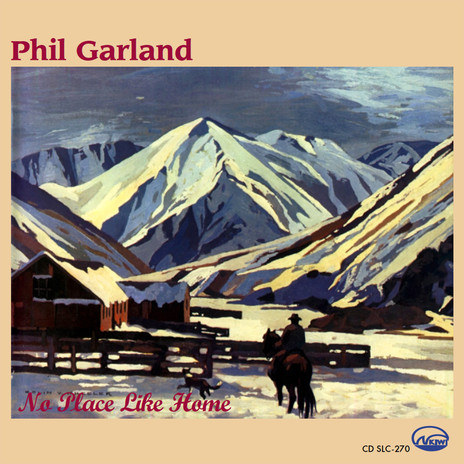

Garland’s legacy of story and song will endure through his work: 19 albums of New Zealand material; his two books, Faces in the Firelight and The Singing Kiwi Songbook; archived radio interviews and television appearances; numerous print articles by or about him, and all the heritage material that would never have seen the light of day if he had not unearthed it. Garland’s archives, including an extensive poster collection, are held in the Alexander Turnbull Library.

--

Read Rosa Shiels's article about Phil Garland's song collecting in the 1960s here