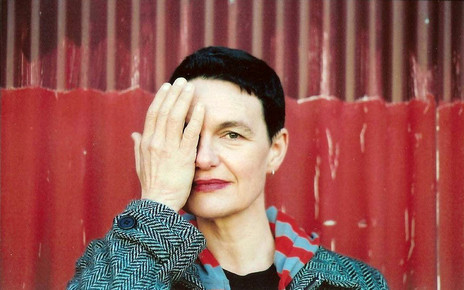

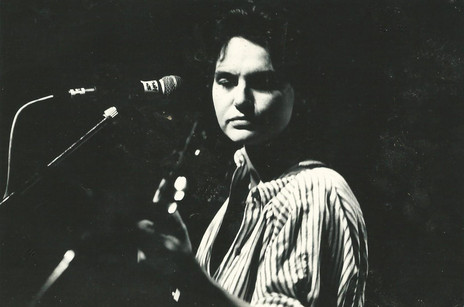

Yet looking back, writing and performing original material has been the thread that runs through her work. “I never thought, ‘I’m going to be a singer-songwriter for the rest of my life’,” says Yates. “I didn’t have the grand master plan.” In 2017 she released her seventh solo album, Then the Stars Start Singing.

Curiously there was no pop music in the Yates household when she was growing up. The family radio was always tuned to the National Programme. Her father, Gavin Yates, presented the station’s children’s holiday series. He was also a minister. Charlotte’s early musical diet consisted largely of Anglican hymns.

At Waimea College in Richmond she learned piano and clarinet, but her academic focus was towards science. Though she felt drawn to music, “it was an adjunct to life really. Not what my destiny was going to be.” Still, an encouraging music teacher introduced her to jazz and the idea of improvisation. She wrote her first couple of songs on piano and – in those pre-Rockquest days – performed them in a school music competition.

She arrived at Massey University in Palmerston North in 1981 to study veterinary science. It was a turbulent time, politically and culturally. It was the year of the nationally divisive Springbok tour, but also a time when innovative post-punk bands were starting to appear on the national stage.

“We had all these people come through for Orientation. The Go-Betweens came through, Nick Cave with The Birthday Party, Hunters and Collectors, every Flying Nun band known to personkind. Split Enz with Blam Blam Blam up front was the first concert I ever went to. So I saw a lot of stuff and lapped it up. I wagged my first anaesthesia class to go and see Avant Garage.”

Around town, local band the Skeptics were trying out on audiences their art-noise experiments. Friends turned her onto Joni Mitchell, Lou Reed, Bob Dylan’s Blood On The Tracks. Through student radio she discovered the likes of The Au Pairs, The Slits and Siouxsee and the Banshees. “The moment there was a woman in a band I was like ‘Who’s she? What’s she doing?’”

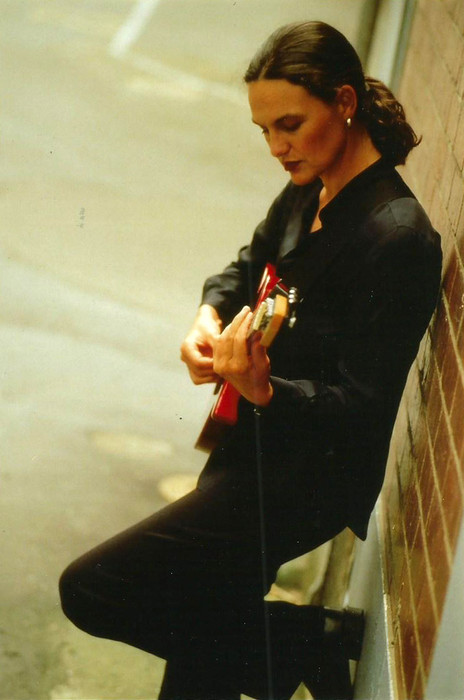

At some point a friend loaned her an acoustic guitar. “For veterinary practice I had to go and work on a sheep farm for six weeks, live in a little shearer’s cottage and help the farmer. And I had a book of Beatles songs and a nylon-string guitar and I learned ‘Eleanor Rigby’.”

Yates moved to Wellington, where musical opportunities seemed more plentiful than veterinary positions.

Back at Massey, Yates met future filmmaker Christine Jeffs, who had already been in an arty indie band. (Their name, Yates recalls, was Insects That Jive Upon Crippled Grassblades.) “I had this interest in making songs up and Christine definitely had a sense of aesthetic.” The two began working on songs together, which led to performing as a duo calling themselves Putty In Her Hands.

Yates’s graduation as a qualified veterinarian coincided with the 1987 stock market crash. Suddenly professional work was scarce. Of the 63 people she had studied with, only one immediately walked into a job. Yates moved to Wellington, where musical opportunities seemed more plentiful than veterinary positions.

Putty In Her Hands recorded an EP for Jayrem, before expanding from a duo to a six-piece band with the inclusion of singer Jackie Clarke and rhythm section of drummer Neil Cruikshank and bassist Gerard Tahu. The formerly acoustic songs sprouted bigger, funkier arrangements. The band performed regularly, including an appearance in the 1990 Rock The Quota concert (later released on video).

Though Yates eventually found full-time veterinary work, the requirements of switching between being Dr Yates and Charlotte Yates: rock musician, just seemed “too schizophrenic”. She lasted six months as a vet.

By the time Putty broke up later in 1990, Yates knew she wanted to write and sing her own material. And the songs were starting to come.

“Some of them were good, some of them weren’t good,” she remembers. “I knew they had something when people had a reaction and could sing stuff back to me. And then one of them cut through, which was ‘Red Letter’. That got some serious traction. That particular song, I just played it on the guitar, and went, ‘Hmm? Hmm!’”

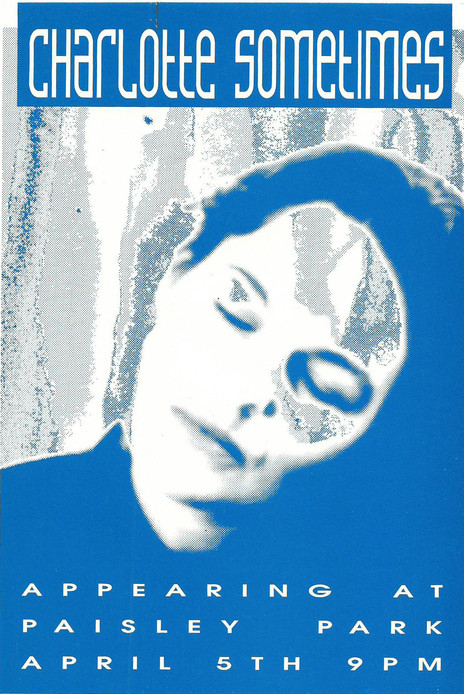

A demo of the song, recorded at Marmalade studio, secured her an Arts Council grant towards making her first solo album. Released in 1991 as Charlotte Sometimes/Queen Charlotte Sounds, the album was noted for its strong intelligent voice and songs that moved easily between the personal and the political.

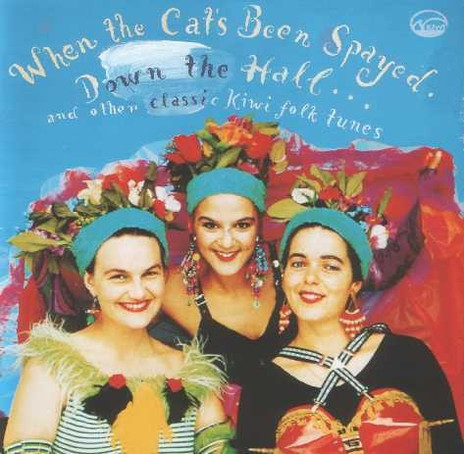

Though her solo career was underway, the next few years were largely dominated by When The Cat’s Been Spayed, the irreverent vaudeville trio in which Yates was joined by singer Jackie Clarke and vocalist/percussionist Robin Nathan. Their name was a veterinarian play on that of popular all-women quintet When The Cat’s Away. Yates also spent time as a coordinator for the Festival Of The Arts in Wellington, and a spell in Australia as director of the Melbourne Fringe Festival.

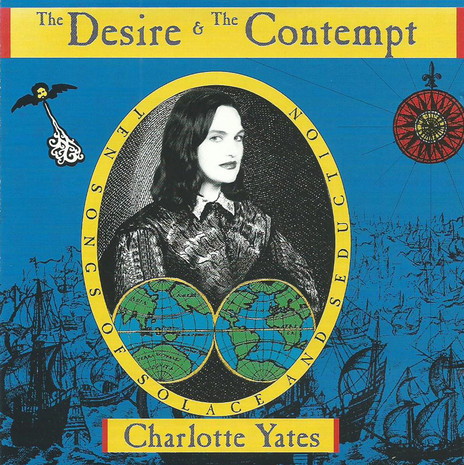

Her second solo album The Desire and The Contempt came out in 1997. Produced by former Crocodile Peter Dasent, it included a couple of vocal quartet arrangements by Tony Backhouse and featured New Zealand expat Jonathan Zwartz on bass. Again the breadth of Yates’s songwriting was on display, from the quiet intimacy of ‘The Summer and The Snow’ to the skanking reggae of ‘Scratches’ and harder-edged rock of ‘Over The Moon’.

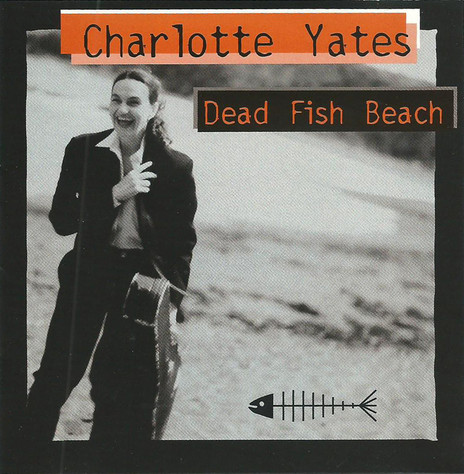

Before her next album, Dead Fish Beach, recorded in Wellington in 2001 and featuring Darren Mathiassen on drums, Yates fell into the first of her “poet” projects.

“I was asked to write a song for a Vietnam tribute and I was flummoxed because I didn’t know anything about Vietnam. I’d been a kid during the Vietnam War, and was not interested in any sort of militaristic situation. They wanted a female song. They’d heard a song on The Desire and the Contempt, ‘Last Night’, and liked that. That was the sound. I felt pretty uncomfortable but I took it seriously and read books, doing research about it.”

The breakthrough came when she stumbled on an anti-war poem by James K Baxter.

The breakthrough came when she stumbled on an anti-war poem by James K Baxter in a pack of clippings from the period. “Most things seemed so dated, but Baxter wasn’t. It leapt off the page at me. I remember thinking, ‘This sounds like a rock song. Wouldn’t it be cool to put this to music?’”

So pleased was she with her discovery, that she began to imagine what a whole album of Baxter poems set to music might sound like. “I just did a wish list. What if I got Dave Dobbyn, what if I got so-and-so, wouldn’t that be cool?”

She approached the late poet’s publishers who put her in touch with Baxter’s widow, Jacquie Sturm. To Yates’s surprise, Sturm gave her approval. Then she sent a tentative proposal out to several record companies, to gauge interest. Universal came back quickly, requesting a meeting. “They said, ‘We really like it, can you do this?’ Game on! They wrote me a letter of support for a funding application there and then.”

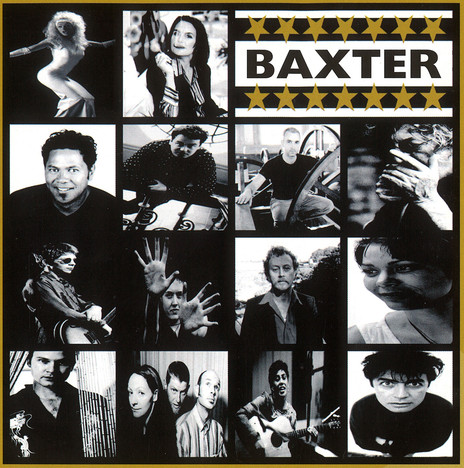

Once the Baxter album was completed – featuring performances by some of New Zealand’s biggest names including Dobbyn, Martin Phillipps, Emma Paki, and poets Sam Hunt and David Eggleton, as well as Yates – a live show was mounted as part of the 2000 International Festival Of The Arts.

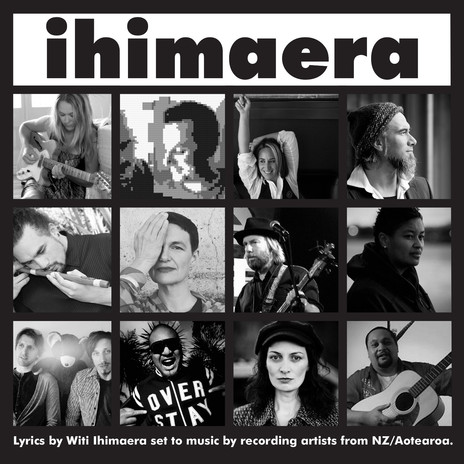

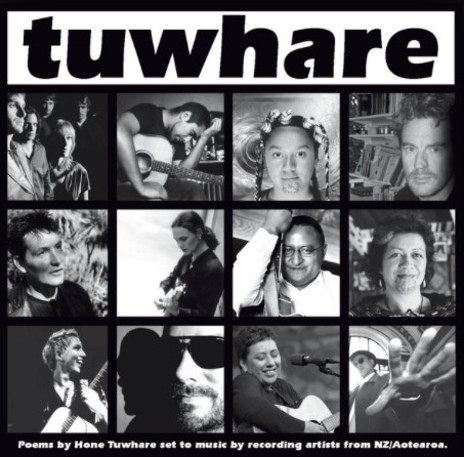

During the next decade Yates devised and oversaw similar projects around the work of poet Hone Tuwhare and novelist Witi Ihimaera. Featured performers included Don McGlashan, Goldenhorse, Whirimako Black, Graham Brazier and Te Kupu.

Working with Māori authors required an extra set of considerations. “As you can imagine, a Pākehā person producing an album of New Zealand’s first published Māori poet and first published Māori novelist, I received some challenges, and had lots of discussions about that.”

A source of support during these projects was Mahinaarangi Tocker, who Yates had first encountered at a women’s music festival in the 80s. (“She did a bitchin’ version of ‘Roxanne’,” Yates recalls of the singer, who died in 2008.)

“I’d take her advice and sometimes I’d sit on my hands and let the iwi deal with it. I hugely appreciated her advice and support. She could argue with me as well, which is a gift to be able to do because I can be pretty strong-minded. But you korero till you sort it out in a respectful way. We all have to live together in a small couple of islands so how are we going to do this?”

The projects have had long lives, especially Tuwhare, which was revisited in 2016 to mark its 10th anniversary.

Yates is sure that working with such a range of artists has informed and influenced her own work. “I got to see how they did things and what they’d come up with. And it was completely fascinating from a behind-the-scenes point of view.”

Her own albums have continued to appear at roughly five-yearly intervals; Plainsong in 2003, Beggar’s Choice in 2008, Archipelago in 2013, and the forthcoming Then the Stars Start Singing.

Yates has continued to forge further strong working relationships, notably with bass player, keyboardist, tenor horn player and recording engineer Gil Eva Craig, who has worked on all of Yates’ albums since Beggar’s Choice.

The new songs inevitably reflect the current phase of Yates’ life, living in Wellington with her civil union partner and stepchildren. “I write middle-aged music now,” she says, laughing. “As one of the kids said to me, ‘Well you’ve got the girl now haven’t you?’ You can’t keep writing about getting the girl. I remember Pete Townshend saying in an interview, ‘Well no one wants to hear me write songs about how much I love my wife.’

“But we do! What do you do when you’re years into a relationship and one of the kids is leaving home? Or you’ve got no time because they’re everywhere? Or you’re not what you were once but it’s better? Or what happens when you have a massive fight but no one’s leaving because we’re kind of over that? The nuances of the life cycle are different. What happens when one of your parents dies?”

The passion for writing burns as brightly ever, though Yates also regards it as a discipline. “Look,” she says, opening her appointment diary of the past year and flicking through a series of pages. “Buy toothbrush … finish lyrics! Song, song. And here, song! I knew I had to have four under my belt by the end of last year, because Gil was going away so I had to have the songs done. And because some of them might not work.”

Yates has also remained conscious of the need, as a music professional, to keep upskilling. “I have a very strong scientific background and way of processing the world, and that married up with the technological revolutions that happened around the time I was starting out. So I was very comfortable with changes from analogue to digital, and becoming your own recording engineer.

“I’m not a purist. I like new stuff. Some stuff just sounds cool. As you learn more on the guitar, or finally learn the difference between a major 7th and a dominant 7th, to me that’s no different from upgrading Pro Tools yet again. But I’m only using it in so far as: does it make what I’ve got to say more fun? Is there more ear candy?”

Every decade or so she has taken some sort of course, “either a tech thing or a guitar thing. I’m just interested.” In the 1990s she studied music technology in Melbourne. Recently she took a three-month online course in songwriting through Berklee College. Though she has released close to 80 original songs, there’s always more you can learn, she says. In particular, studying songwriting has made her a better editor of her own work.

“That’s my definition of success. Do I like what I’m doing, and does it allow me to live with my family, and get better?”

--

Read more: Charlotte Yates profiles Mahinaarangi Tocker for AudioCulture