It was as if Fred Astaire had joined the Rolling Stones, with Lou Reed along as a stylist.

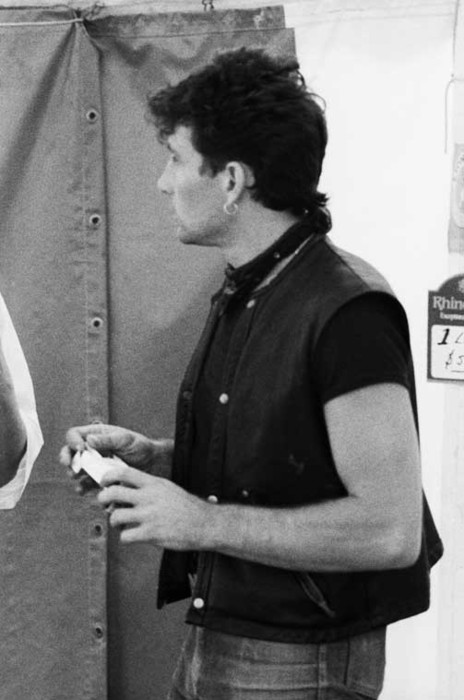

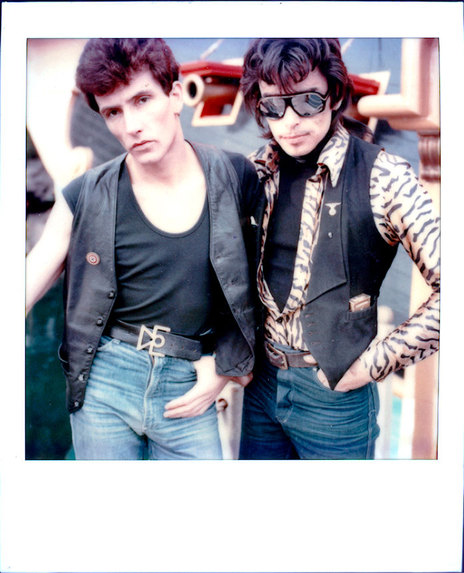

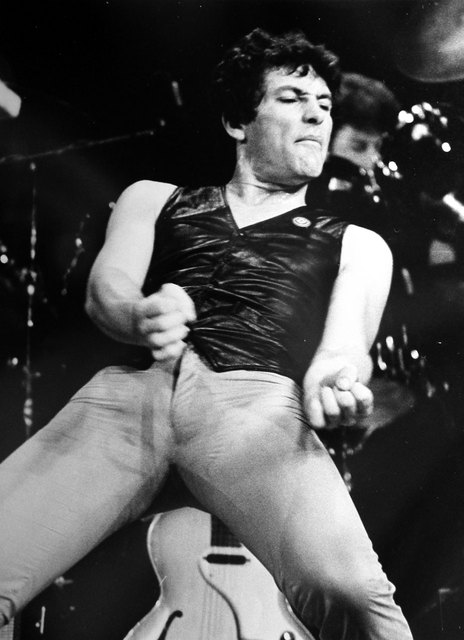

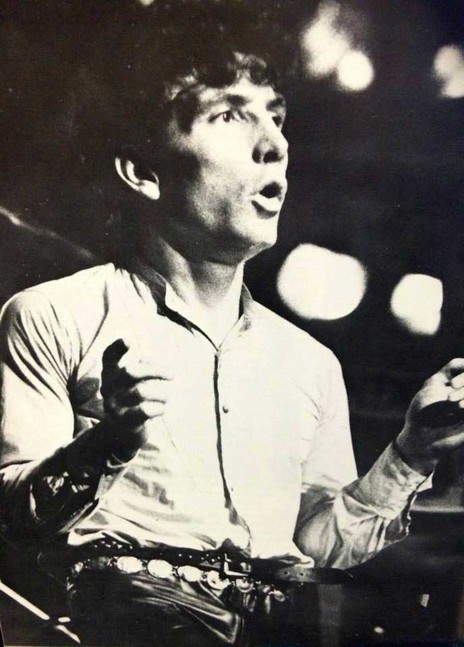

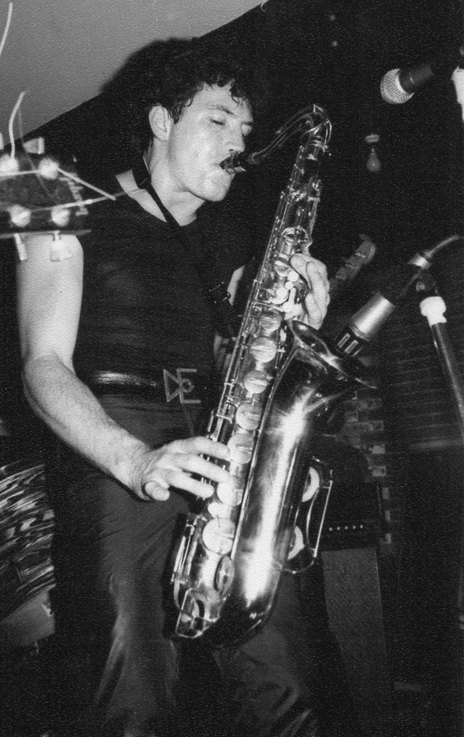

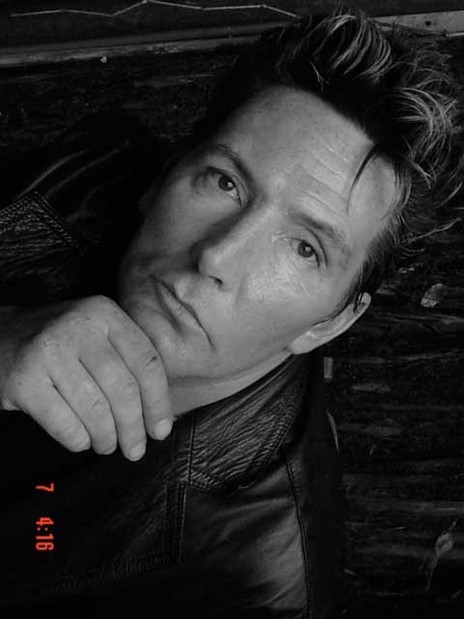

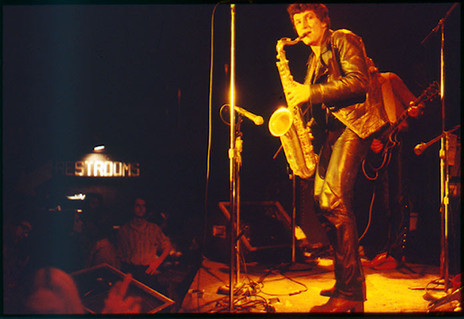

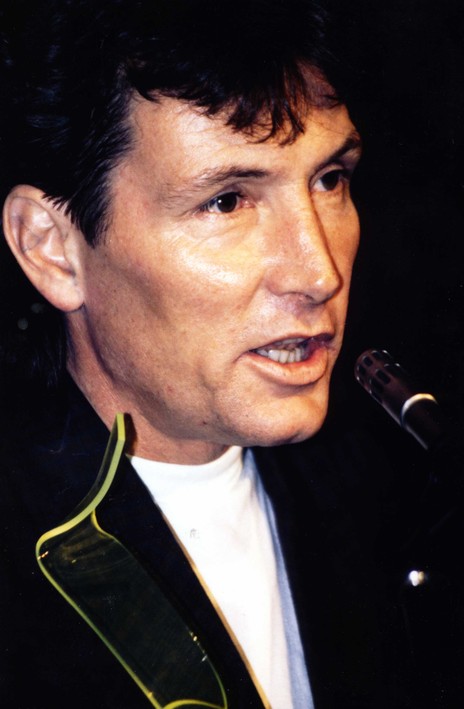

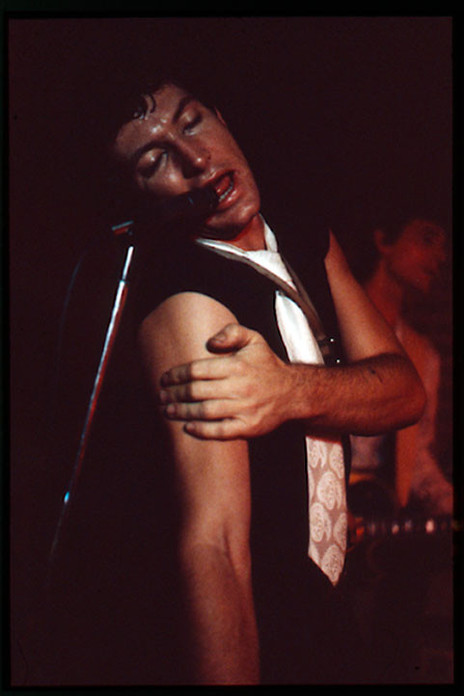

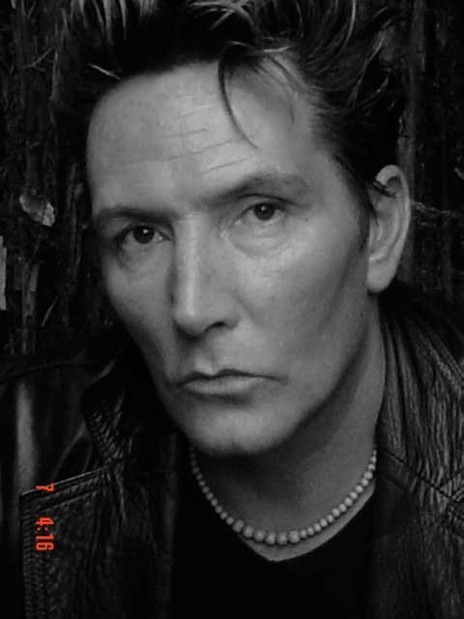

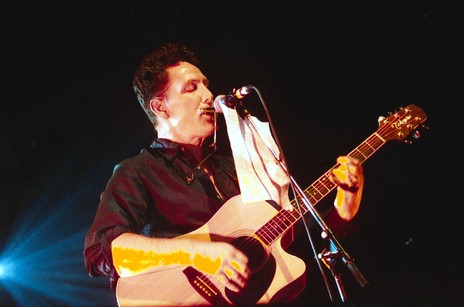

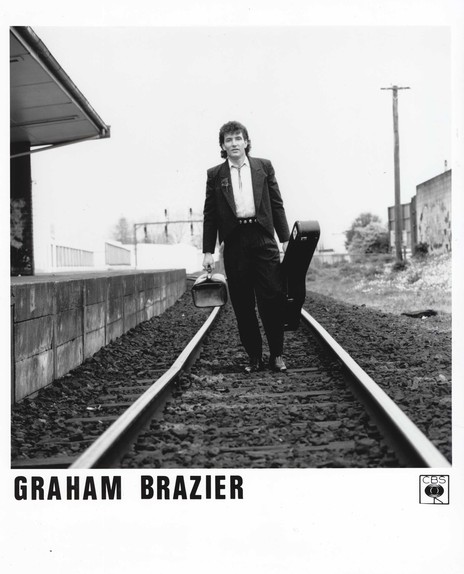

On stage, he was spellbinding. Sailor liked to keep its audiences waiting, then arrive roaring like a twin-guitar V8. Brazier hit the stage running, his long legs in trousers as tight as leather condoms, his torso – powerful from years of hard manual labour – squeezed into a tank top. The wide leather belt around his slim waist exaggerated his already broad shoulders. His Cuban-heeled boots made him lean forward, as though poised to run for the try line on Carlaw Park, or to react to a left hook.

It was as if Fred Astaire had joined the Rolling Stones, with Lou Reed along as a stylist. A naturally fluid dancer, his moves were musical, menacing – and entertaining. He copied no one, and should have trademarked his choreography. The day Brazier died, his friend the drummer Wayne Bell wrote a prose poem in tribute to his stagecraft:

On a good night, he’d fling a cigarette six feet in the air, spin three times on those Cuban heels and, in a shower of sparks, clap the cigarette out above his head perfectly in time with the music.

On a good night, he’d heave his tambo skyward and, without looking, let it fall over his outstretched arm, sliding up to rest on his shoulder.

On a good night he might suddenly fall to the floor and do 10 to 15 one-handed press-ups.

On a good night, you’d play out of your skin because it was a hellish crazy ride!

Truly mesmerising.

What a rock star!

RIP GB.

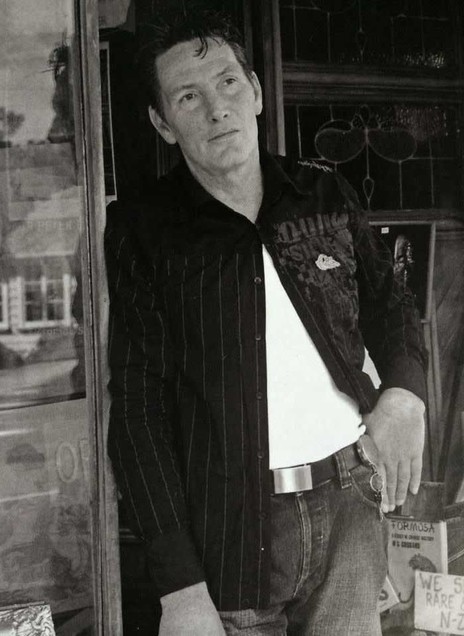

As well as being a flamboyant rock’n’roller of world class – our first original rock star – Brazier was a romantic and a poet, a great reader and a dedicated socialist. ‘Blue Lady’ told one side of his story: it was a love song to a syringe. ‘Billy Bold’ told another: his pride in his left-wing ancestry. He specialised in myth-making, and most of those myths emerged, enlarged, from his own life story. The best songs after Sailor’s halcyon late 70s were biographical: ‘Billy Bold’, ‘No Mystery’ and ‘Juan Pacenta’ from his classic first solo album, Inside Out; ‘Motorway’ about his friend Paul Hewson, who overdosed; ‘New Tattoo’ and ‘Under A Surrey Crescent Moon’ from latter-day Sailor; ‘Desert Of Love’ and ‘Closing Time’ from his last solo album, East Of Eden.

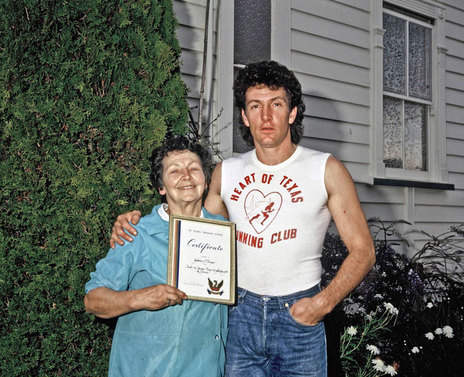

Brazier would have liked the James Dean reference of that last album, but he actually grew up south of Mt Eden, in the unflashy Auckland suburb of strugglers and Bible-readers, Mt Roskill. Halfway down Dominion Road, his beloved mother Christine ran a renowned, cluttered second-hand bookshop, and introduced her son to customers such as Frank Sargeson, James K Baxter and Kevin Ireland. He developed a lifelong passion for American popular culture and hard-nosed literature: Bukowski, Burroughs, Ferlinghetti. His father Philip was “born in the sight of a Liverpool dock”, became a merchant seaman and an early member of the New Zealand Communist Party; he was a unionist, a social campaigner, and died an alcoholic.

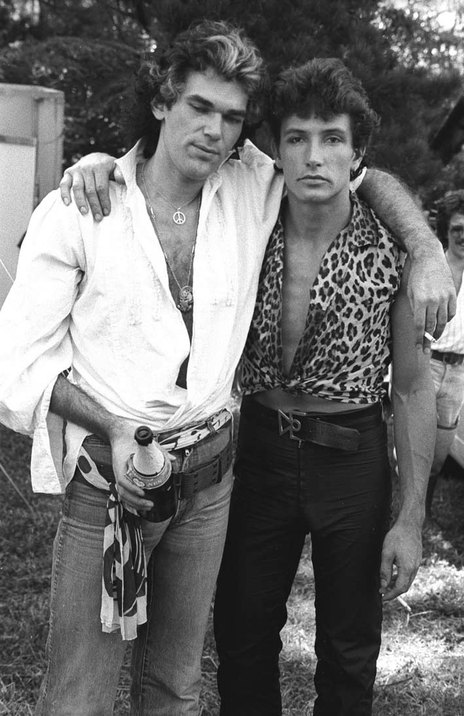

For a short while, Brazier went to Mt Roskill High, running with gangs and playing league rather than attending classes. He once described the school as offering three career options – sport, music, and crime – and he tried all three before settling on music. Like Springsteen, Brazier’s song titles were taken from panoramic B-movies, but before he chose to eke out a living as a musician he did the hard yards on rubbish trucks and the wharves. But he was a snappy dresser, and turned countless heads when he mixed with Auckland university friends such as Dave McArtney and Harry Lyon: he was on campus as a gardener.

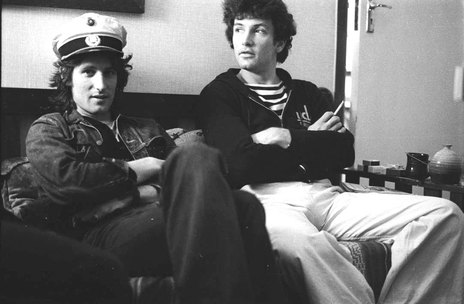

As an acoustic trio – whose tastes included Robert Johnson, The Beatles, reggae and the Velvet Underground – Brazier, Lyon and McArtney began playing at the Kiwi Tavern on the edge of the university. Martin Edmond, one of the bohemian crowd in which they mixed, wrote, “I remember afternoons in the back bar of the Kiwi, when Graham would have his harmonica and Dave his guitar and they would improvise medleys while the rest of us banged or clapped or shouted along.”

Forming Hello Sailor in 1975 with rhythm section Ricky Ball and Lisle Kinney, the band soon held court nearby at the Globe on Wakefield Street. The stage was miniscule, and the bar not much bigger – but it was packed with a dedicated crowd, who enjoyed the mix of smartly chosen covers and originals that became the sound of city. The genre was nicknamed Ponsonby reggae, at a period when the rundown suburb was, Brazier once said, full of “Polynesians and pirates”. In a desultory era of jukebox pub bands, it was Sailor’s originality – and their full-throttle rock’n’roll risk taking – that kept the crowds returning.

Simon Grigg has written that seeing Hello Sailor at the Globe Tavern in 1975-76, playing “furious sets filled with Velvets and other pre-punk rock’n’roll – stuff that was otherwise impossible to hear anywhere else around Auckland at the time – was transforming. Graham in his tight black T-shirt every weekend on that tiny stage.” Young Dude and apprentice record engineer Ian Morris dragged Stebbing producer Rob Aickin along and insisted the company sign the band; Alastair Dougal took his Rip It Up partner Murray Cammick and the magazine’s commitment to local music took shape. “There was a time before Brazier, and a time after,” recalled Grigg, who became a music industry entrepreneur. “Hello Sailor changed everything.”

Two Seminal albums were recorded At Stebbing’s, ‘Hello Sailor’ and ‘Pacifica Amour’.

The band regularly filled the two larger pub venues in central Auckland, The Gluepot in Ponsonby and the Windsor Castle in Parnell. Two groundbreaking albums were recorded for Stebbing’s Key label, Hello Sailor and Pacifica Amour. Although receiving little airplay outside of Radio Hauraki, the songs became New Zealand anthems: Brazier’s ‘Blue Lady’ and ‘Latin Lover’, McArtney’s ‘Gutter Black’ and Lyon’s ‘Lyin’ in the Sand’. On the more jaded Pacifica Amour, Brazier’s contributions reflected his cinematic writing: ‘Tears of Blood’, ‘I’m a Texan’ and ‘The Boys in Brazil’. His harmonica playing gave their sound an earthiness, his saxophone some swing, but mostly it was his commanding baritone voice that dominated. Coming from deep in the diaphragm, it was dramatic and well-enunciated: rock’n’roll theatre.

Brazier was often brilliant, and often erratic: so was Hello Sailor itself. The band had a reputation for blowing the big gigs: the almost reckless foray to Los Angeles in 1978, a desultory period in Australia, the 1980 Sweetwaters gig when they returned. Performing while out-of-it was commonplace. “The whole prevailing attitude in the late 70s was fucked,” Harry Lyon said in 1986. “It was sleazy and out of it, and we got sucked into it.”

Brazier and his cohorts may have carried themselves with a swagger, but he was prone to insecurity. He also had hedonistic tastes: his literary heroes Lou Reed and William Burroughs had their demons, too. In 1974, aged 22, he tried heroin for the first time; it would become a scourge for many contemporaries thanks to its availability through the Mr Asia drug syndicate. Fifteen years later, Brazier told writer Joanna Wane, “It was very available and I was very susceptible to it. I went through a period when I thought it was romantic and neat. Now it’s a disease I will have to live with for the rest of my life.”

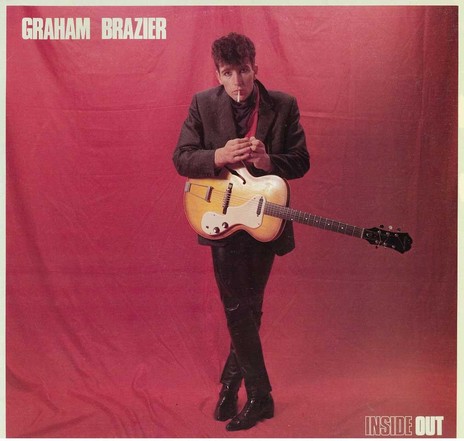

His demons became well documented in the newspapers in 1981 and 1982 when Brazier was convicted on two hard drugs charges and the attempted burglary of a chemist’s shop. For many months he faced a prison sentence; while waiting he recorded the best album of his life. Funded by his then-manager Chris Cole, Inside Out was recorded on a $4000 budget thanks to his friends from Hello Sailor and DD Smash donating their time. With so much hanging over his life, Brazier’s talents rallied with taut songs that were street-wise and melodic. “Brazier’s songwriting and stentorian voice have never been better,” wrote Nick Bollinger in 2010, “and among the many fine songs is one that ultimately attained the status of a classic. Inspired by riots in the Liverpool suburb of Toxteth and his father’s northern English roots, ‘Billy Bold’ has the feel and fervour of an Irish rebel song. Today’s audiences won’t let Brazier finish a show without singing it.”

The song’s occasional appearance on TV’s Radio With Pictures gave it an audience that was all but denied by radio programmers. Promotional opportunities were limited: Brazier’s sentence of periodic detention required him to be in Auckland on weekends, and the record company was unwilling to spend money. (The album was funded and recorded independently; Polydor offered Brazier a distribution deal for it rather than signing him direct.)

Inside Out was a cult hit only, and regarded as a lost classic until its reissue on CD in 2005.

So Inside Out was a cult hit only, and regarded as a lost classic until its reissue on CD in 2005. ‘Billy Bold’ and most of the other songs from Inside Out – among them ‘No Mystery’, ‘Organisation’, ‘Six-Piece Chamber’, ‘Juan Pacenta’ and ‘High Wind In Jamaica’ – were the heart of his set list for years. Many of them reflected Brazier’s besieged situation, and his self-image as an underdog, an outsider, the people’s champion. He dedicated the album to “… everyone and anyone who never had a chance.”

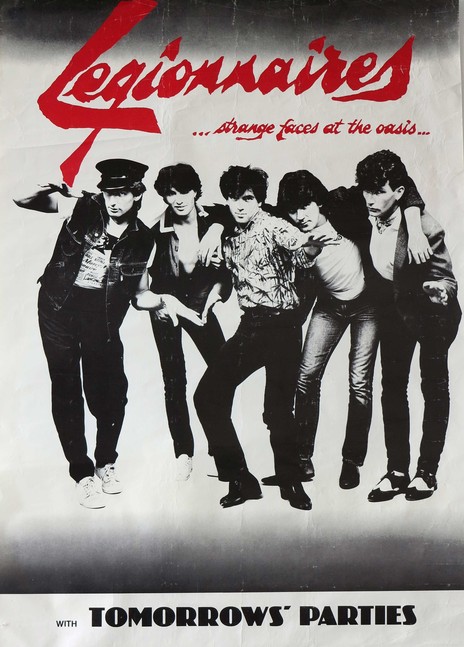

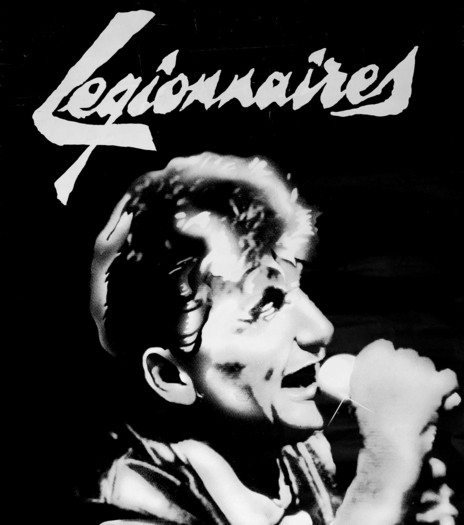

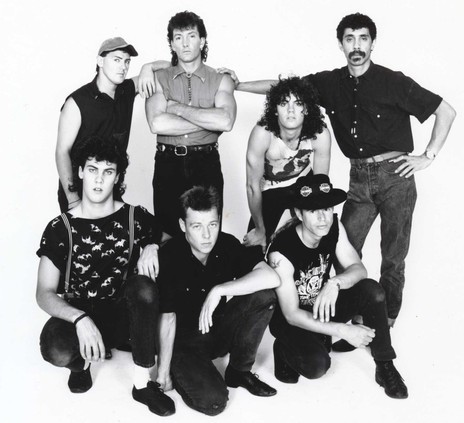

Once he was able to leave town, a group called Brazier’s Legionnaires was formed, concentrating on material from Hello Sailor and Inside Out. Quite quickly the frontline was replaced by Dave McArtney and Harry Lyon after their stints with the Pink Flamingos and Coup D’État. It was almost inevitable that Hello Sailor would once more put to sea.

This happened in 1985, and the following year Sailor re-entered the studio to record an album. Shipshape and Bristol Fashion was a curiosity: it now seems to epitomise the flashy zeitgeist before the 1987 stockmarket crash. It was funded by a company formed to take advantage of tax breaks, and released by a record company formed by Harlequin Studios. Liam Henshall, an English musician with some minor dance-oriented chart success, was brought out to produce. He re-recorded songs from their previous albums, as well as getting Brazier to re-record ‘Billy Bold’ and McArtney’s solo hit ‘I’m In Heaven’. The resulting album was a culture clash, as if 1970s rock veterans were given vouchers to spend in a provincial 1980s UK fashion boutique. One track succeeded, ‘Fugitive For Love’.

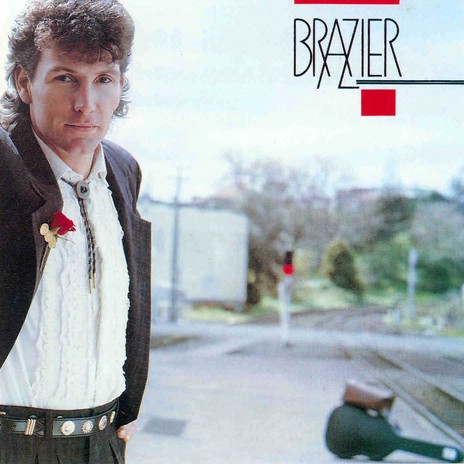

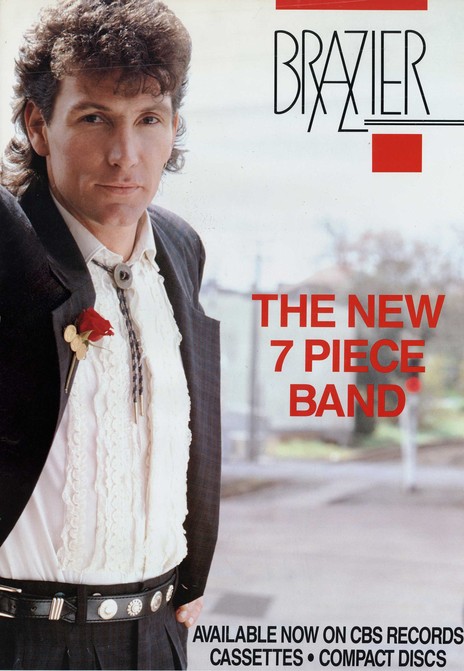

The album quickly disappeared, as did the solo album that Brazier recorded almost immediately afterwards. Released in 1988, Brazier also suffers from its era – guitar rock from the black-clad musicians at Auckland’s unhip Wildlife nightclub – but strip away the layers and Brazier’s acoustic roots are showing on songs such as ‘Motorway’, ‘North To The South’ and ‘Satellite Town’.

It received tepid reviews, but Brazier – despite battling hepatitis and pneumonia – was writing again, and performing often. His solo shows returned him to situations in which he was vulnerable. Asked by Wane in 1990 if he still used drugs, he replied “Does a gambler go to the race track? I do the best I can.”

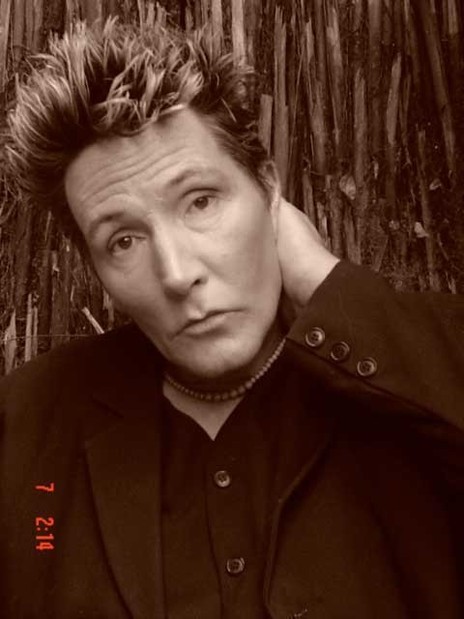

In the 1990s, Sailor came to the rescue, regularly playing gigs as the original acoustic trio or as the full band. Hello Sailor – the Album came out in 1994, and featured several strong songs by Brazier, including ‘New Tattoo’. Eventually, the rhythm section settled with Ricky Ball returning on drums, and Paul Woolright on bass (he had been in Ticket with Ball, and the Pink Flamingos with McArtney). For the next two decades the band performed more widely than just pubs: corporate gigs, cafes, theatres, gang headquarters, and on national tours. The inclusion of McArtney’s ‘Gutter Black’ on the TV series Outrageous Fortune also buoyed their revival. Two more albums would follow: an acoustic greatest hits, When Your Lights Are Out (2007), and Surrey Crescent Moon (2012), which featured new originals. Brazier’s title track was one of the strongest, with critic Graham Reid describing it as “part-poetic rumination and part-reflective murder ballad grounded in the Celtic tradition.”

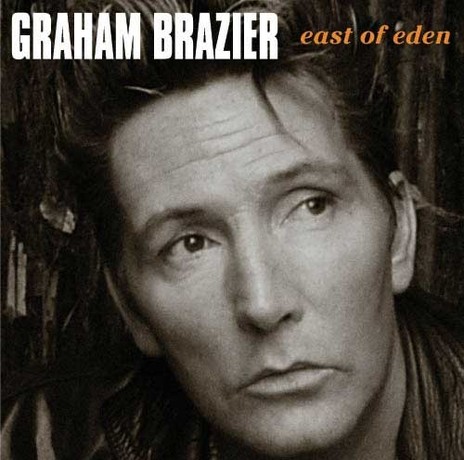

Surrey Crescent Moon was a swansong for the band, but Brazier’s own final statement had appeared eight years earlier: East of Eden. Released on Murray Cammick’s Wildside label, and sympathetically produced by Rikki Morris, songs such as ‘Long Gone For Good’, ‘Winter Of Discontent’, ‘Late Night Music’ and ‘Mr Asia’ looked back – with pride, romance and regret. It was a return to the consistent standards of Inside Out.

Recently, Brazier was close to finishing his fourth solo album, working with Alan Jansson, the producer and co-writer of OMC’s worldwide smash ‘How Bizarre’. Early reports were that the sessions were going well, if slowly. Even though Dave McArtney died in 2013, plans were underway for a Hello Sailor 40th anniversary tour to take place in late 2015. But these were put on hold in July when Brazier suffered a heart attack, followed shortly afterwards by a stroke. He died in an Auckland rehabilitation unit on 4 September 2015.

The day after he died, at Mount Smart Stadium in Auckland, the Richmond Bulldogs were playing the Te Atatu Roosters in the final of rugby league’s Sharman Cup. Just as the game was about to start, everyone present stood for a minute’s silence in tribute to Brazier. He was a passionate fan of Richmond, who won that day, and of league in general. In 1988 a fan spotted him in the gents, just before the kickoff of the New Zealand vs Australia final. “There was Graham, adjusting his hair in the mirror, with a suit, swaying,” recalled friend John Greenaway. “Hey Graham,” he said. “What’s with the suit?” Brazier replied, “I’m singing the National Anthem.”

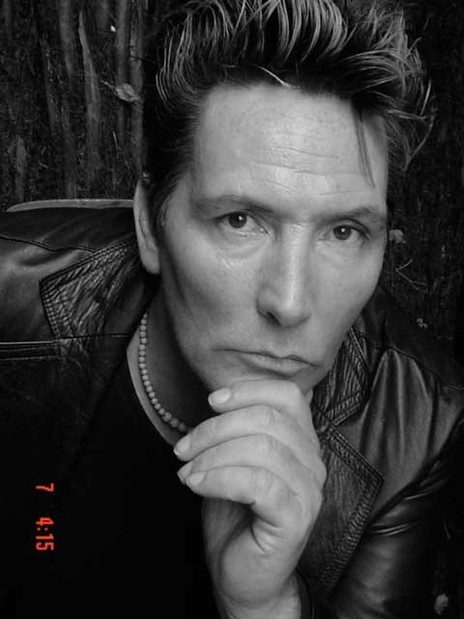

New Zealand music fans mourn an extravagant character who charmed all he met and left behind a legacy of unforgettable songs and performances. A great showman, a self-deprecating ham, a raconteur fond of a grandiloquent phrase, a singer with a dramatic voice, he would probably like to be remembered as a gentleman, a good friend, a great reader – and a genuine street poet.