There were no musicians in the Dougal family, though his mother enjoyed music.

“It was a typical diet of that time: South Pacific, The Sound Of Music, all those Rodgers and Hammerstein shows – which I still love, actually – and classical music.

“My mum always told me that I sang before I talked. ‘Love and Marriage’ by Frank Sinatra, and ‘Davy Crockett’, which I apparently used to sing as ‘Born on a mantelpiece in Tennessee …’ to my parents’ amusement.”

By the mid-1960s The Beatles had arrived, and Alastair – like most of his generation – was galvanised. “I went to see Help! I was 12. I loved it, and went out and bought the single, which is just a genius bit of work.

“Actually, ‘Help!’ was the second single I bought. The first was ‘Theme from The Avengers’, because I was besotted with Diana Rigg as a 12-year old. The third single I bought was ‘Dance To The Music’ by Sly and The Family Stone. With those three singles you might have my musical taste encapsulated right there.”

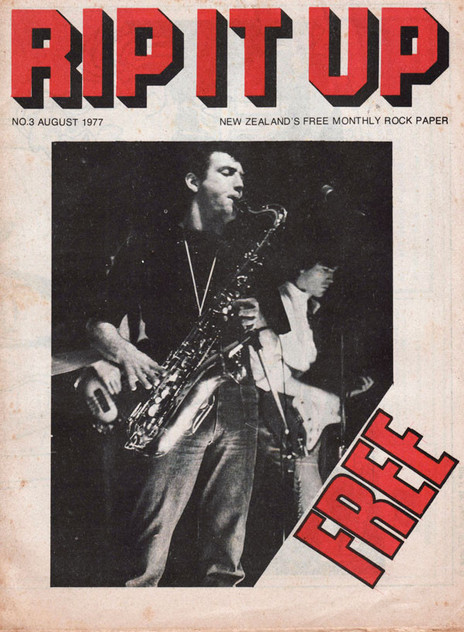

At St Heliers primary school he met Murray Cammick, with whom he would later start Rip It Up. They got to know each other better at Glendowie College.

“Murray was obsessed with Otis Redding. He was a member of the Stax-Volt Appreciation Society – Sam and Dave, Carla Thomas, all this stuff – and used to get all the little newsletters mailed out to him. So he had an influence on pulling my taste towards rhythm and blues. But I was still a big Beatle nut. The first album I bought was Sgt. Pepper.”

At 15 he started playing the bass guitar. “There was a school band and they needed a bass player. [Fellow student] Glenn Barclay had got a bass and he played guitar so I bought his bass and Jansen Bassman 50 and a duo box with two 12-inch speakers and joined the band.”

Other than being shown how to tune the instrument, Dougal taught himself the bass guitar.

Other than being shown by Barclay how to tune the instrument, Alastair taught himself. “I remember, to the annoyance of my parents and my brother, endlessly playing ‘Badge’ by Cream because it starts with that bass riff. I must have played that two thousand times trying to get the part off.”

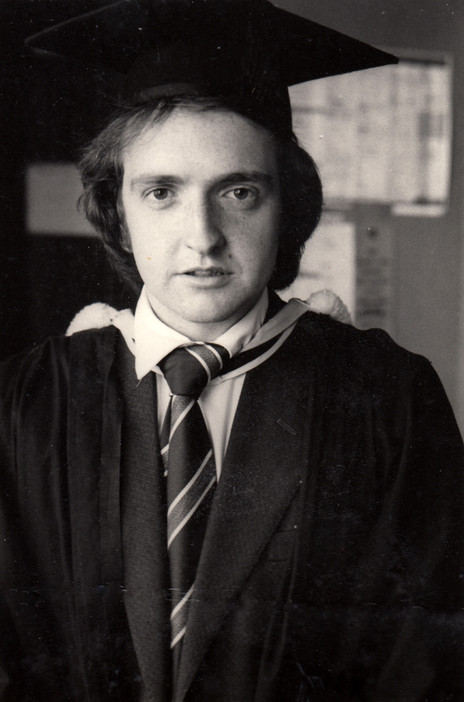

In 1971 he went to Auckland University to study history and political studies. The university touring circuit was underway, and the campus was humming with hairy underground bands. His favourites were Ticket, with bass player Paul Woolright and drummer Rick Ball (“I’m always a sucker for a good rhythm section”) and the early version of Dragon. “They were quite a different Dragon in those days. I remember they used to do Stevie Wonder’s ‘Living For The City’ and Neil Sedaka’s ‘Bad Blood’. I liked those songs, and I like it when people are diverse like that.”

He joined the University Jazz and Blues Club and helped organise gigs and jam sessions. Though he didn’t yet have the confidence to get up and perform, it was through the club that he met John Malloy, a pianist and guitarist with whom he would form Top Scientists a decade later.

It was also through the club that he first encountered Rick Bryant, who in those days was dividing his time between lecturing at Victoria University and singing with the Wellington-based Mammal. Bryant was in Auckland with Mammal to play a campus gig. “We had given the band a box of beer,” Alastair recalls. “After the gig we were cleaning up the cafeteria and Rick went to get his beer and found he didn’t have any. I knew he was an English lecturer. When he turned to me and went, ‘Some ****’s nicked me ****in’ piss!’ I thought, well that’s pithy and to the point.”

Alastair began writing music reviews for Craccum, the student paper. Murray Cammick was the designer; one of the editors was Frank Stark. “I remember it going to press at midday Friday and Frank would be sitting there writing the editorial at eleven. Then they would lay it out and someone would say ‘Oh we need another couple of paragraphs’, so he’d do them and it would be perfect. I was in awe of his skill to write great prose and just slap it down.”

Alastair also played music with Stark in a fledgling band, which also included fellow student Bruce Belsham on saxophone, future actor-comedian Deb Filler singing, and drummer Mike Donnelly.

After completing his BA, Alastair briefly moved to Australia at the invitation of guitarist Henry Jackson, a former stalwart of the Auckland blues and rock scene, who had moved to Melbourne. “I was pursuing the rock‘n’roll dream but it all went a bit awry. I thought I was going to join a band that was already playing but in fact I was going to join a band that barely existed.”

Returning to Auckland and university, he enrolled to study law. It was early in his second year at law school that Cammick came to him with an idea: why don’t we start a music magazine? “And I guess I thought, well why not?”

Hot Licks, the country’s only national music monthly, had closed down the previous July after just over two years, and Murray perceived a gap in the market.

“It was Murray’s idea and Murray’s big enthusiasm, but he didn’t want to do everything and wasn’t confident about his writing, so he thought, ‘Well Alastair can write, he can be the editor, I can be the graphics and layout guy.’ And he was necessarily the business guy. I guess through Craccum he’d got some idea of the logistics of how to run a newspaper, which I hadn’t got a clue about.

“I remember we met [Hot Licks founder and editor] Roger Jarrett. Murray organised for us to have lunch with him, to find out what could he tell us if we were to do this. But other than that we just launched into it blindly.”

“Why would a middle-aged woman want to open a bank account in the name of Rip It Up?”

The pair put up $500 each to set up a company. “For some reason my mother opened the bank account. I have no idea why, because I was 24 by then. Perhaps because neither of us had an income? Anyway I remember Mum going down to the ASB in St Heliers. ‘Okay what is the name of the account?’ ‘Rip It Up.’ Excuse me? ‘Rip It Up.’ This dumbfounded conversation about why a middle-aged woman would open a bank account in the name of Rip It Up! But my mother was a stubborn woman in some ways and probably quite quietly proud of her eccentric son.”

Friends from school and university were recruited as writers: Bruce Belsham, Glenn Barclay, John Malloy, Frank Stark. Roger Jarrett would be an occasional contributor.

The first issue of the free monthly appeared in record shops in June 1977. The Sex Pistols had just released ‘Pretty Vacant’. Rip It Up #1 had The Commodores on the cover. “That was very much Murray’s thing. He had this idea, unlike Hot Licks, that R&B was an important music form. But it certainly became apparent fairly quickly that putting the Commodores on the cover would almost be a provocative act to some people. ‘What? Black guys in silver spangly suits?’ Chris Knox would have been outraged!”

But Cammick always credits Alastair for arguing that Hello Sailor should be the magazine's first New Zealand cover act, in issue #3.

As well as being the editor, Alastair contributed substantially as a writer. “I always loved reading criticism and I still do. It’s a branch of literature, obviously. I remember great writers, great aesthetes like Richard Williams who wrote for Melody Maker, a beautiful writer and I found his tastes sympathetic to mine. He stretched me because he would promote jazz and avant garde and classical. Robert Christgau – it’s amazing how you can read those old reviews and he’s pretty much always on the money. I don’t always agree with him. I’m not very interested in alternative music and there are all sorts of areas I’m interested in that he dismisses, but in the areas where we overlap – country, hip-hop, pop, rock – he’s got phenomenal ears.”

Early issues of Rip It Up featured Alastair’s reviews of local live shows, from Living Force to Hello Sailor, plus interviews with Kiwi chart-topper Mark Williams, recent Split Enz departee Mike Chunn, and the ascendant Hello Sailor, in which he drew from Graham Brazier such flamboyant quotes as “I’d like to see Kiri te Kanawa wearing black leather, PVC, and safety pins.”

He also interviewed international visitors including Joe Cocker, Ry Cooder, Melanie, Nick Lowe, and little-remembered Australian tourists The Ted Mulry Gang. He wrote: “Like Hush and Skyhooks (and come to that, like many Australians), they’re loud, brash and vulgar and a lot of fun.”

When Graham Parker and The Rumour toured, he took to the road, reporting on their shows in the four main centres and cornering Parker, guitarist Brinsley Schwarz and Stiff Records’ founder Dave Robinson for interviews.

His enthusiasm for music and musicians shone through in his writing, but he could also be frank in his criticisms, such as the occasion he confronted Dragon’s Marc Hunter. It was around the time of the group’s second Australian-recorded album, Running Free. “I’d been given an advance copy. When I mentioned this, Marc fixed my gaze and said ‘What do you think of it?’

“I was a callow young man, so I told him what I thought. ‘I don’t think it’s as good as the last album,’ I said. Immediately, I knew that was a stupid thing to say. Marc was a large man and a volatile one. I thought I might be a dead man. Marc took his time, leaned right in my face and said: ‘Perceptive, aren’t you?’ Hilarious. He had a great sense of the theatrical.”

A high point of his Rip It Up career was meeting James Brown.

A high point of his Rip It Up career was meeting James Brown, who came to Auckland in June 1978 to play at Phil Warren’s Shoreline Cabaret. “I went backstage with Murray, Bryan Staff and photographer Gillian Chaplin. We were told Mr. Brown was having his hair done and there would be no women [allowed] in Mr. Brown’s dressing room. Murray, Bryan and I went in and Mr. Brown was sitting in front of the dressing room mirror with a barber’s cape on and his hair in rollers while someone worked on his hair. There were several of his people in the dressing room. A very small man but he was friendly and smiley.”

By 3.30am Mr. Brown had changed his clothes, his coiffure was complete, and he was off to catch the 5.30am plane to Australia, leaving a the parting message, which Alastair duly relayed in the next issue of Rip It Up: “I just want to say to the people out there – ‘Hope you live to 200 years and I live 200 years minus one day so I never know beautiful people like you have passed away.”

In 1979 Alastair entered his last year at law school and, with academic pressures mounting, handed over editorship of the magazine to Murray. He stresses that throughout this time, Murray had been “carrying the brunt. He was literally putting in five or 10 times what I was doing.

“Also I did start to feel uncomfortable about being a musician and writing critically about local bands. That was an uncomfortable spot to be in. I wrote one review of Split Enz I know Tim Finn took great exception to.

“The other thing I started to find doing record reviews ... it’s actually bloody hard work. There are some records where you have an immediate reaction – this is fantastic or this is dreadful – but most records fall into that horrible middle area. It’s got something but what’s it got? And how good is it? It’s hard to have an attitude to something you almost don’t have an attitude to. I was having to listen to things I didn’t particularly want to listen to. And I wasn’t getting paid for it.”

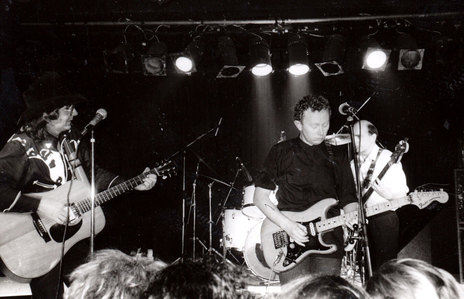

THE TOP SCIENTISTS WERE NOTED FOR THEIR EXCEPTIONAL TIGHTNESS AND ABILITY TO WIN OVER DRINKING CROWDS WITH ORIGINAL SONGS.

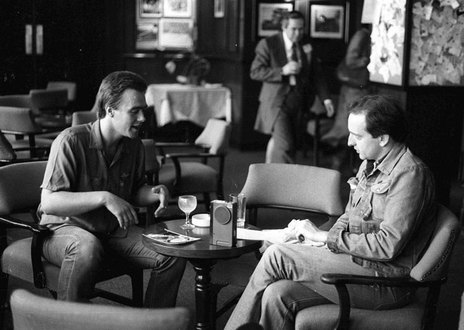

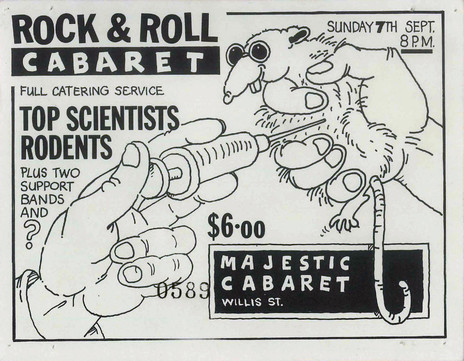

Meanwhile Alastair was stepping up his activities as a musician. A rehearsal group with John Malloy and guitarist Gary Langsford became a more serious proposition when Rick Bryant joined, having recently relocated from Wellington. The repertoire consisted mostly of Malloy originals, an energetic cross between pub-style R&B and new wave rock. They named themselves Top Scientists – an in-joke, given they included a doctor (Malloy), a law graduate (Dougal), a fine-arts graduate (Langsford) and a former university English lecturer (Bryant), with drummer Michael Polglase completing the lineup. (Polglase later became an IT consultant.)

“Once John Malloy and I were out pasting posters up, just in that lane by Real Groovy, and these cops pulled up. The usual story. ‘What are you guys doing?’ To John: ‘What’s your profession?’ ‘Doctor.’ ‘Are you shitting me?’ And then he turned to me. ‘Okay, I suppose you’re a doctor too’. And I said, ‘No, I’m a lawyer’. He didn’t know whether to believe us or not but they left us alone after that.”

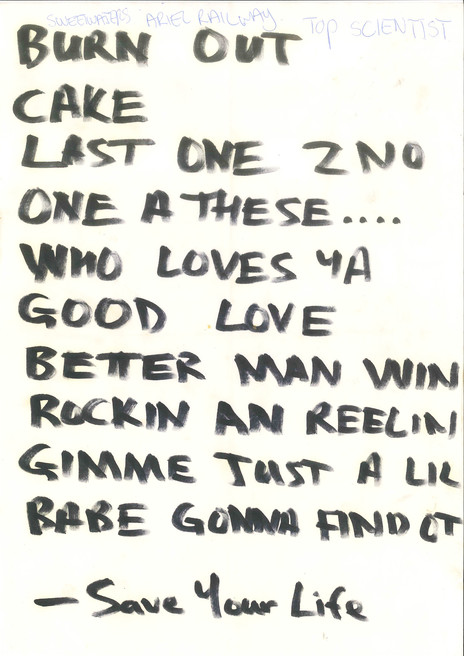

By mid-1980 Top Scientists were gigging in pubs, initially around Auckland, then nationwide. Though noted for their exceptional tightness and ability to win over drinking crowds with original songs – no mean feat – they never released any records, and in early 1981 the group dissolved.

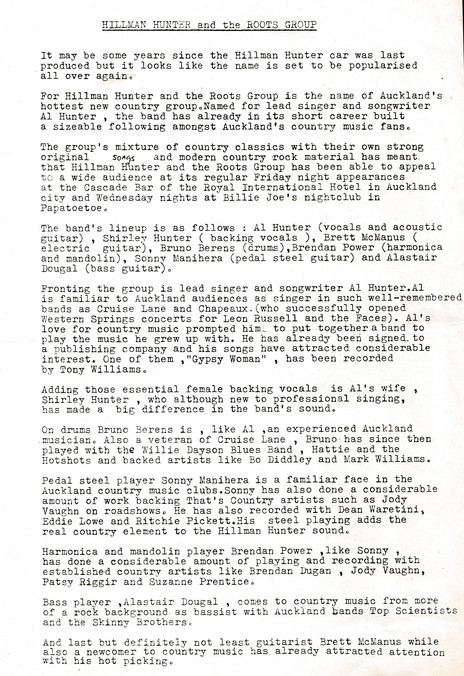

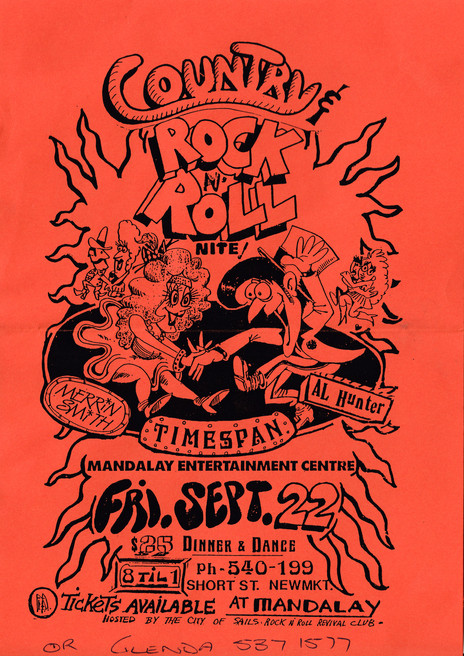

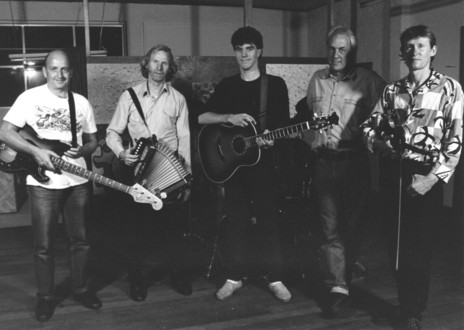

Soon after, Alastair embarked on a working relationship with country singer Al Hunter that would continue until the mid-1990s, first as a member of Hillman Hunter and the Roots Group, later The Al Hunter Band.

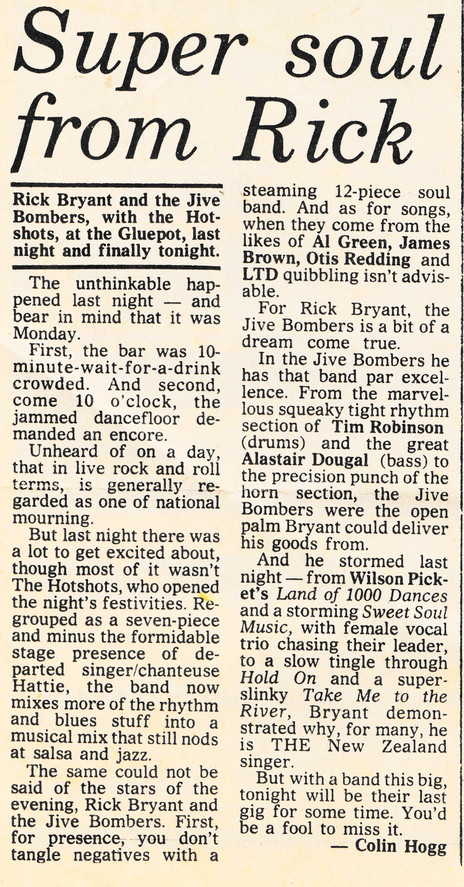

Around the same time he played a crucial role in the 1983 formation of Rick Bryant and the Jive Bombers, a big R&B showband modeled on the classic American soul revues, complete with horn section, female backing singers and glittery attire.

Bryant recalls: “Alastair chose a lot of the first repertoire, which became very popular because it was good; a mixture of quite well known but not done to death classics, with obscure but great songs that should have been hits”.

“There was an upturned car and broken glass everywhere. ‘That’s unusual’, I thought.”

The band is well represented by the 1984 album When I’m With You, part of which was recorded live at Wellington Town Hall and captures the band at the height of its sequin-and-satin glory. Alastair would continue to play with The Jive Bombers until 1985, all the time keeping up the country gigs with Al Hunter.

“I remember playing with Al in a bar on the night of the Dave Dobbyn gig that turned into the Queen Street Riot [7 December 1984]. I came out of the pub to get my car after the gig, totally unaware of what had been happening outside. There was an upturned car in the middle of Wellesley Street and broken glass everywhere. ‘That’s unusual’, I thought.”

In 1986 he began working by day in the legal section of the Housing Corporation, and became a solicitor in the Henderson branch the following year. The playing continued by night, mostly with Al Hunter, whose band lured large crowds to its Saturday afternoon residency at the King’s Arms. There were also occasional gigs led by Hunter Band guitarist Red McKelvie, which would be billed as The Red McKelvie Band. By the early 1990s McKelvie, infatuated with Cajun music, had taken up button accordion and formed Mumbo Gumbo, in which Alastair also played, along with Jono Lonie (fiddle), Ian Thomson (drums) and singer-guitarist Glen Moffatt.

In 1993 Hunter’s album The Singer was released, featuring Alastair on bass. But by the time the singer returned from a solo road trip to promote the album, Alastair’s diary had filled up with Mumbo Gumbo and Red McKelvie Band dates as well as gigs led by Glen Moffatt, so he and Hunter parted ways.

The 1990s were busy: “Three gigs in a row in one night and we never repeated a single song.”

It was a busy time. Alastair recalls one New Year’s Eve around this time when “we played the Kings Arms as the Red McKelvie Band, then the Tartan Bar under the London Bar in Wellesley Street as Mumbo Gumbo, and then the Java Jive as the Glen Moffatt Band. Three gigs in a row in one night and we never repeated a single song.”

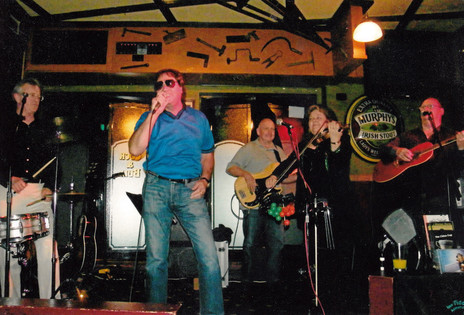

The mid-90s was boom time for Irish bars and Mumbo Gumbo capitalised on the craze by shapeshifting into an Irish band called Poitin. Glen Moffatt bowed out of the lineup at this point (“he hated Irish music” Alastair recalls), but Alastair continued to play with him in The Glen Moffatt Band, and appeared on his debut album Somewhere In New Zealand Tonight, released in 1995.

Poitin gave way to Feck, fronted by singer Derek Motley. Poitin worked extensively in the Irish pubs of Auckland, including a residency at The Claddagh in Newmarket and Irish venues such as The Immigrant and Dogs Bollix. Feck continued until 2001 when Motley moved to Glasgow.

Prior to Feck, Alastair had also been picking up a lot of casual gigs on the country scene, but because Feck were so busy over their five-year run he had become unavailable as a freelance. “Once Feck ended, I found I’d lost all my contacts for pick up work,” he says. “The phone stopped ringing.”

In 2006 he signed up to another Irish outfit, The McSweeney Brothers, with Paddy Hallissey, Marian Burns and Eddie McIntyre “playing what’s left of the Irish pub circuit.” He continues to play with the McSweeneys. St Patrick’s Day is still a big day, and usually finds Alastair playing three consecutive gigs, from morning until late into the night.

“I like the way Lorde likes pop music and thinks it’s an art, and I totally agree.”

His ears remain open, his tastes broad.

“I was walking to work one day and there were about 80 teenage girls sitting outside the Town Hall at 8 o’clock in the morning so I looked up what was on and it turned out that night there was a band called The 1975 playing there. I thought, ‘That’s interesting’. And now I really love The 1975, they’re an amazing band and I’d never heard of them.

“I was, and still am, interested in commercial music because I think, well, if that’s what’s resonating with the most people it’s probably got some substance. That’s why people like it. I’ve never been an anti-populist. I’m a poptimist. I like what’s popular. I’m not necessarily going to love it all, but I like to think ‘Why is it popular?’ And sometimes I agree, yes it’s great.

“I like the way Lorde likes pop music and thinks it’s an art, and I totally agree. There’s an art to a good pop song.”

And he’s still available for hire, should Lorde ever need a bass player.