AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Red Hot Peppers

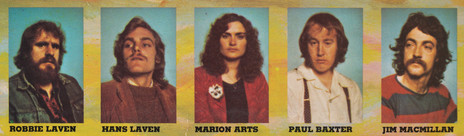

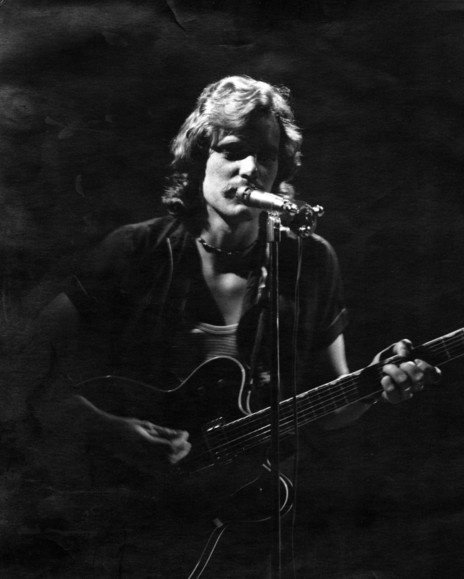

Not to be confused with American funk-rockers The Red Hot Chili Peppers (who would not come along until well into the following decade) or British pub-rockers Chilli Willi and the Red Hot Peppers (from a few years earlier), Red Hot Peppers combined folk, jazz, pop, country and assorted ethnic styles into a bright and original package, centred on the supple and emotive voice of Marion Arts and multi-instrumental colourings of Robbie Lavën.

In 1975 and 1976 they toured the country extensively and made a classy album, Toujours Yours, before heading to Australia where they continued to perform and record for several more years.

Born in Amsterdam during the Dutch famine of 1944 – the infamous “hongerwinter” that took place in the German-occupied Netherlands – Robbie Lavën grew up around music. His father played chromatic harmonica and “that ubiquitous Dutch party instrument, the piano accordion”.

His maternal grandfather was also passionate about music, and played organ and brass instruments in the local brass band.

Some of Robbie’s early musical impressions were of his father’s Sunday morning 78 records sessions, which exposed his young ears to Louis Armstrong, The Hot Club Of France, Edith Piaf, Les Paul & Mary Ford, and the Dutch Swing College Band.

By the time he reached his teens, rock’n’roll had hit Amsterdam. Black artists such as Little Richard and Fats Domino made a strong impression.

His parents had just bought him his first guitar when they decided to emigrate to New Zealand; he taught himself to play it on the boat. The family settled first in Pukekohe, then Te Awamutu and, from 1963, Tauranga.

“My adolescent identity was kicked around brutally by emigrating. I immersed quickly but never fully in Kiwi culture. Within a month I designed a Māori logo at Pukekohe High School for consideration by the local rugby team. Got a commendation! I was exposed to country and western and mainly white pop and rock’n’roll in the milking shed where I worked after school, and I saw the Howard Morrison Quartet, Toni Williams and a Māori showband at the Pukekohe Town Hall.”

This turned out to be the concert at which the Howard Morrison Quartet’s hit ‘My Old Man’s An All Black’ was recorded.

Lavën was in New Zealand in time to witness the popular ascendance of The Shadows

Robbie was in New Zealand in time to witness the popular ascendance of The Shadows, Cliff Richard’s backing band and a successful instrumental combo in their own right. The first music he encountered at school dances and social functions had consisted of a pianist, occasional drummer “and in Te Awamutu, home of world-champion cornet players, a couple of cornets. But when The Shadows led the charge of the guitar-band brigade, every town and village in the country grew guitar bands and I instantly became a lead guitarist.”

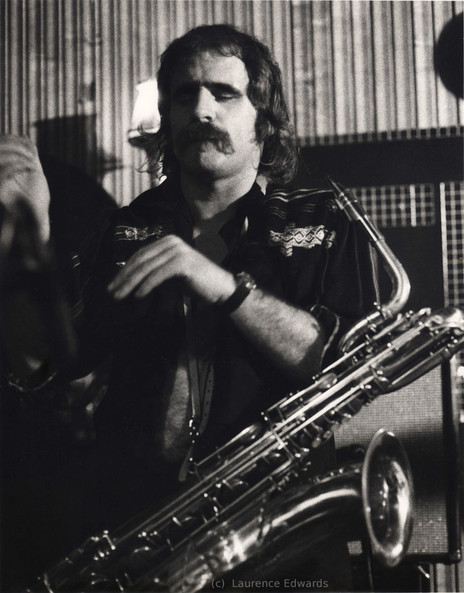

During his last year of school he also embarked on the saxophone, teaching himself on an instrument he borrowed from a local marae. As part of Tauranga band The Supertones, he helped back contestants in the Johnny Cooper Talent Show when it visited the city.

In 1965 Robbie went to Auckland University to study languages and law. By this time Beatlemania had edged The Shadows aside. Robbie embraced the new fashion, playing guitar in Moses and the Munks, a popular if short-lived beat group that included future Underdogs singer and Red Hot Peppers producer Murray Grindlay, and Ticket frontman Trevor Tombleson.

At the same time New Zealand was discovering folk music, which proved especially popular on the university campuses. Robbie ended up organising the folk music concert of the University Arts Festival and, for a while, running the University Folk Club “where I performed on anything I could get my hands on, for the fun and anarchy of it.”

His involvement in the folk scene led him to join The Mad Dog Jug, Jook and Washboard Band, “which seemed to be what I had been looking for, without knowing what jug band music was.” The Mad Dogs were indeed a jug band, drawing on the rural blues and hokum music of the 1920s and 30s, and inspired by contemporary American revivalists like The Jim Kweskin Jug Band. Their members included Paul “Cat” Tucker, Chris Grosz, Andrew Delahunty, Tom Crannitch and Pete Kershaw.

But Robbie remained musically omnivorous. At a university lecture theatre in 1965 “in an audience of about fifty” he heard the Indian sitar master Ravi Shankar perform.

“I was completely captivated by the modality that locked into much Celtic and British folk music, and the huge expanse of improvisation which locked into jazz. Auckland music shop Lewis Eady’s happened to have a sitar so I used my bursary money to get it.”

He learnt the rudiments of sitar playing from Raman Chhiba (who also taught the instrument to guitarist Doug Jerebine and BLERTA keyboard player Chris Seresin). Robbie was soon able to get around the instrument “convincingly enough to play at the Sunday Hindu church gatherings in Ponsonby with Raman.” Raman can be heard on the Peppers’ first album.

Robbie continued to acquire and learn new instruments. In The Mad Dogs he took up mandolin and banjo. When he backed the folk and blues singer Val Murphy someone gave him a dobro.

“Also at that time there were auction rooms all over New Zealand, secondhand and pawn shops with deceased estate stuff. They were a treasure trove of instruments. I had succumbed to collector’s addiction and a sixth sense for instruments and music. For instance I acquired four Grafton white plastic alto saxophones, various mandolin family instruments made by George Moore in Gisborne during the war, all sorts of other instruments from the auction rooms, and lots of unusual records.”

After graduating from Auckland University, he moved to Hamilton to work. He ran the Hamilton Folk Club and organised the 1971 Hamilton Folk Festival.

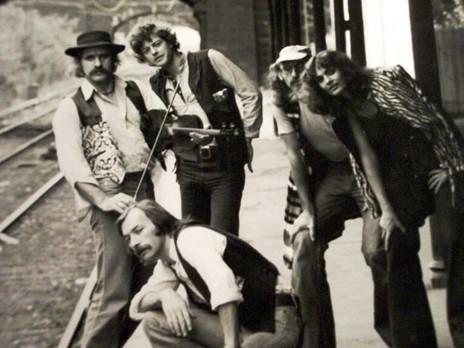

Though his next band had its roots in the Hamilton folk scene, its specialty was stylised reproductions of 1950s rock’n’roll. The 1953 Memorial Society Rock’n’Roll Band put on a big show, complete with period costumes, glittering horns and, when the opportunity presented itself, a motorcycle, which was ridden onstage during ‘Leader Of The Pack’, its throttle revved on cue in the choruses. “Sometimes gang members volunteered and would, proud as punch, polish and shine their bike before the concert.”

The 1953 Band played various shows up and down the country, with a notable appearance in January 1973 at the Great Ngāruāwahia Music Festival (where Robbie also sat in with Wellington jug band The Windy City Strugglers and performed a set of Indian music with Raman Chhiba). They finished the year as winners of the New Zealand Entertainer of the Year group award.

Like Robbie Lavën, Marion Arts was a child of music-loving Dutch immigrants

Like Robbie Lavën, Marion Arts was a child of music-loving Dutch immigrants. Born at Mount Maunganui, she grew up in Tauranga, where she studied piano and classical guitar while teaching herself pop and folk styles. At 14 she was a founding member of the Tauranga Folk Club and was writing her own songs.

As a singer, her first influence was Edith Piaf, whom she heard when an aunt from Holland came to stay, bringing with her the album of Piaf’s so-called “suicide tour” (during which the morphine and alcohol-addicted chanteuse collapsed on stage.) Marion remembers listening to the record at the door, stunned. “My aunt translated the dramatic content for me, perhaps initiating my love for the art of chanson which contained heavier lyrics that American pop did.”

Though Piaf’s influence would be enduring, and the chanson approach to lyrics would later affect her own writing, she also admired Joan Baez “though perhaps it was the Hispanic aspect of it that appealed most”. Sandy Denny of Fairport Convention was another favourite, along with The Beatles. Later she would discover and be influenced by jazz vocalists such as Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan.

Marion first sang with the 1953 Band after the group’s usual singer Helen Phare abruptly resigned on the eve of a gig, opening for visiting New Orleans R&B legend Clarence “Frogman” Henry.

She had met Robbie two or three years earlier at a University Arts Festival in Wellington, where he was playing with the Mad Dogs and she was there as a solo performer. He had accompanied her on an improvised version of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Suzanne’. More recently she had been singing with brassy Hamilton funk-rock outfit, Swellfoot’s Assembly.

After her hasty initiation into the 1953 Band, Marion sang regularly with the group. But by the end of 1974 they had disbanded, and Robbie briefly moved to Christchurch where he played with Chris Grosz’s band Pork Chops.

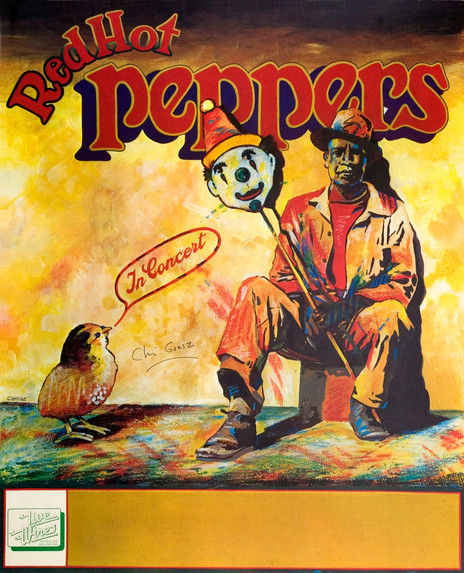

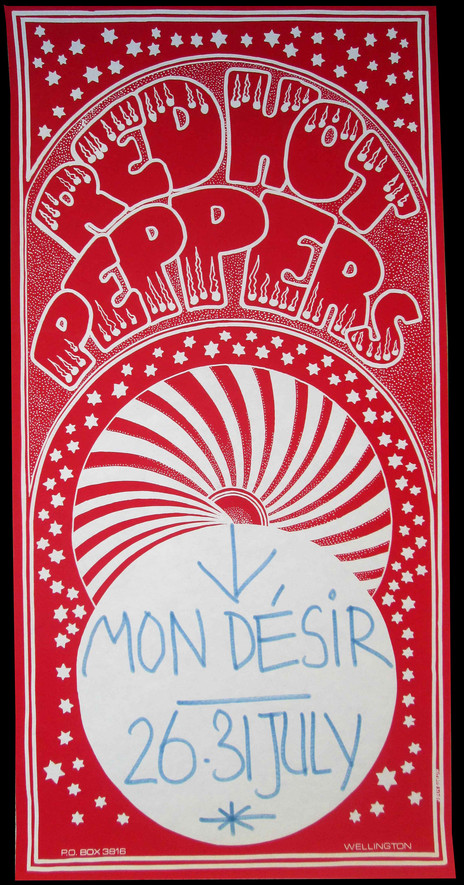

The Red Hot Peppers’ name was an homage to Jelly Roll Morton’s pioneering 1920s jazz band

On his return to Hamilton, he and Marion set about forming Red Hot Peppers. The group came together over Easter 1975. The name was an homage to Jelly Roll Morton’s pioneering 1920s jazz band The Red Hot Peppers.

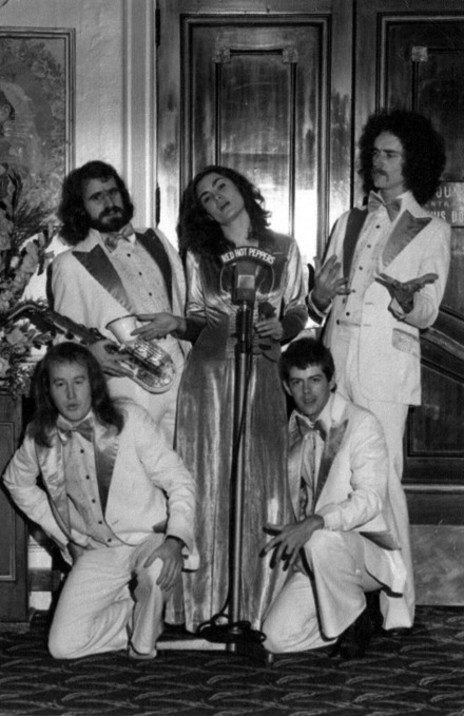

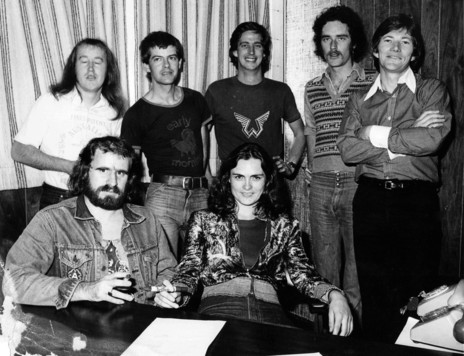

“The band grew out of our very broad musical interests in a natural, unplanned way,” Marion remembers. “Both Robbie and I were natural stage performers as well as stylists. We both loved the many instruments that came our way. We just added other musicians in, as they were needed and as they were interested.”

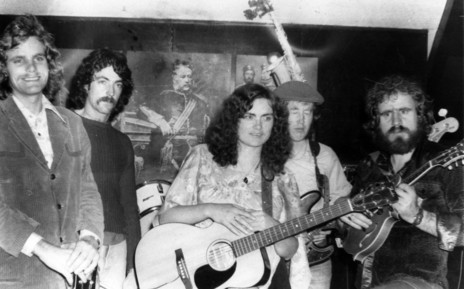

Peppers had a similar sense of theatre, humour and flamboyancy as the 1953 Band. Initially they were joined by guitarist Mike Farrell, who had played with Wellington psych-rockers Tom Thumb but developed a strong interest in folk and acoustic styles. He was eventually replaced by Robbie’s brother Hans Lavën.

Bass player Paul Baxter was recruited from Swellfoot’s Assembly; drummer Jim MacMillan was a Hamilton musician. Both were good harmony singers, and Baxter had a lively stage presence. “He had a great feel for our flamboyance and extravagance,” says Marion.

Rather than focus on a particular era as the 1953 Band had done, Peppers set about building a repertoire from a wide range of sources: singer-songwriters Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan, British folk-rockers The Strawbs and Fairport Convention, jazz divas Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald, as well as funk and blues. They also included original material, initially by Robbie but later focusing on Marion’s songs.

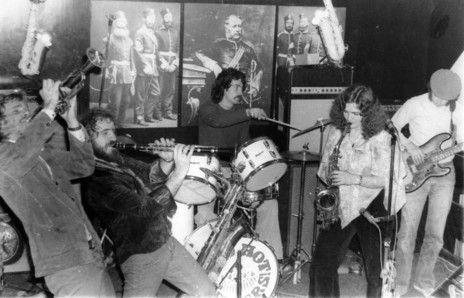

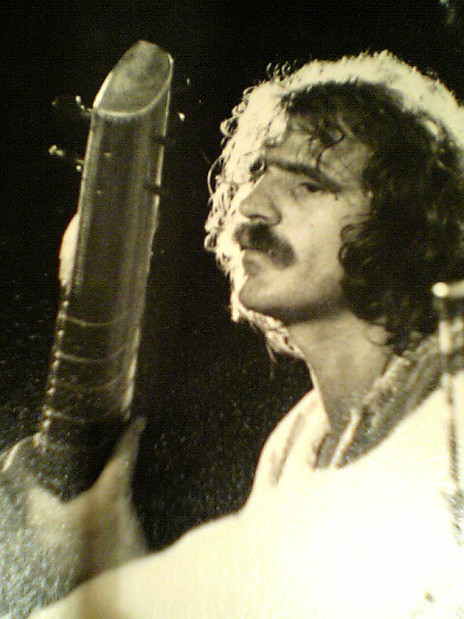

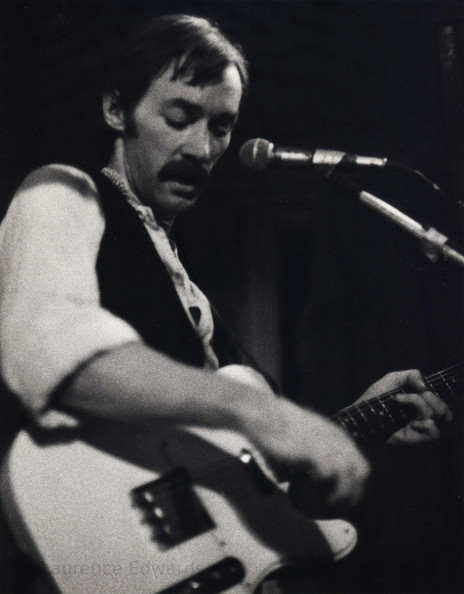

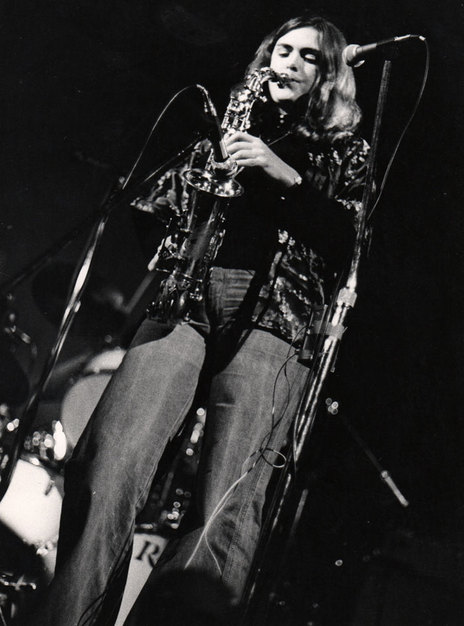

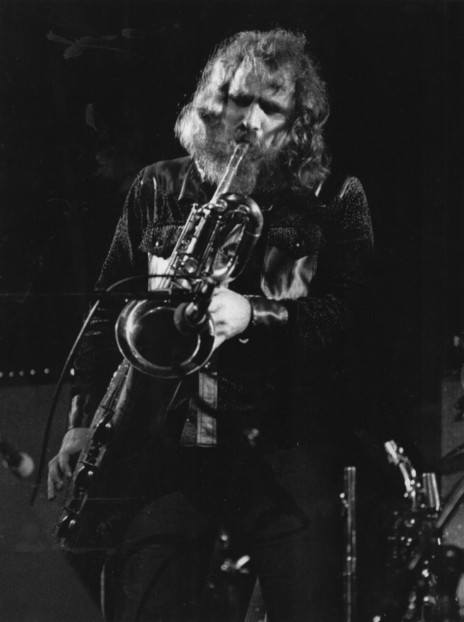

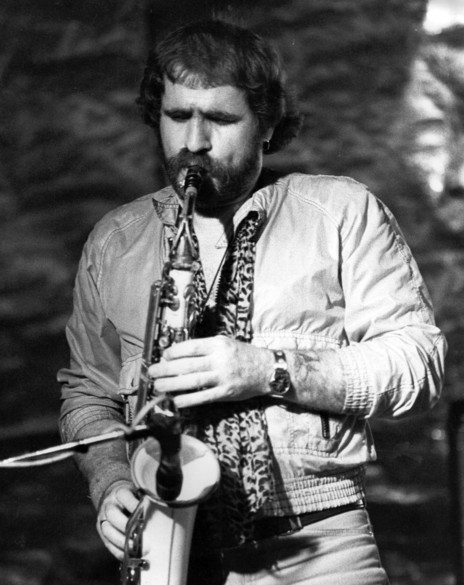

Successive newspaper profiles of the band described Robbie’s growing collection of instruments: by 1976 there were 100, of which he played 23 on stage. These included a Greek bouzouki and a yangqin (a 64-string Chinese dulcimer) was put to good use. Marion also played saxophones, and she, Robbie and Hans – who played trumpet as well as guitar – could transform into a horn section when necessary. On stage the group was lively, theatrical, full of musical surprises and unlike anything else you would hear in New Zealand at the time.

The group quickly built an audience in Hamilton. There was strong student support from Waikato University (where Marion was studying languages and literature) as well as from the folk scene, in which both Marion and Robbie had been involved. They would perform regularly to enthusiastic crowds at the Hillcrest Tavern.

Soon they began venturing out of town. Robbie says: “At the time there was at least one pub in every town that had music regularly, Wednesday to Saturday, from 7 to 10pm and sometimes on Saturday afternoon as well, all with a dance floor and a stage.”

Some venues were more hospitable than others. “We were at our best at concerts and at pubs with a concert feel, such as the Mon Desir in Auckland. We could not afford to avoid gigs, but met resistance and disrespect for woman performers at hard-out drinking-hole rock pubs.”

Touring also sometimes brought them into conflict with moteliers.

“One motel owner would barge in early in the morning and viciously berate us for still being in bed and not making up the beds. Another motel owner, in Whangarei, called the police – us obviously being dirty, drug-crazed rock musicians – although it did not stop him from taking our money. Marion and me were about to be arrested triumphantly after the police found some Dutch liquorice! But eventually they went away empty handed and in bad grace.

“Touring itself had charms, for a while. We saw a lot of places that we would not have seen otherwise and met a lot of nice people. Many gigs were great and kept us motivated.”

the Aussie sound crew aimED fireworks at the performers. One blew a big hole in Lavën’s sitar

Travelling with Robbie’s vast array of instruments presented its own challenges. “Repair and maintenance and simple things like replacing broken strings were a never ending saga, and the added costs were problematic. And because there was such a lot of stuff on stage, things were knocked over at times. At the Great Ngāruawāhia Festival the Aussie sound crew thought it groovy to aim fireworks at the performers. One lodged in my sitar, blowing a big hole in it.

“I have from time to time made conscious efforts to restrict the number of instruments, but keep on finding that the advantages of diversity outweigh the practical disadvantages. Also, it is what I do. Even when I play with other multi-instrumentalists, the audience identifies me as the bloke with the instruments.”

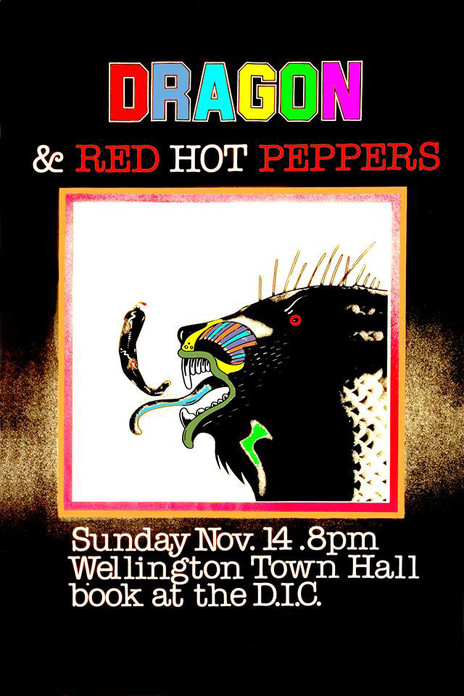

In 1976, the Peppers played support for a number of international acts, including Ralph McTell, Steeleye Span, Flo and Eddie, Renee Geyer, J.J. Cale and Canned Heat. The Canned Heat concert, at the Wellington Town Hall in July 1976, stands out. Robbie: “We were hot and Canned Heat were incapacitatingly stoned and couldn't get it together. Bob Hite had to be pushed on to the stage, yelled “Are you having a good time?” and then sat down for a rest.”

Realising that their elaborate style was best suited to a concert format, in October 1976 the Peppers mounted an ambitious 21-date national tour, sponsored by the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council and organised by promoters Graeme Nesbitt and Martin Firth, taking the group from Kaikohe to Invercargill. Many of the gigs were in seated theatres.

“In the smaller centres attendance was modest but enthusiastic,” recalls Robbie. “In the larger centres it was as if we were real rock stars, the public lining up to get tickets and wildly responsive during the concerts.

“We tried to keep the surprise and fun elements. For instance, Graeme and Max Winnie, who was doing the sound, did an acoustic number from behind the mixing desk in the middle of the audience to start the second set.”

In anticipation of the tour, the NZ Herald ran a piece that described the band’s versatility, which ranged from “rock‘n’roll to jazz, contemporary ballads and country. And beyond that there is jug-band music, jigs and reels and English folk music. Two examples of the Red Hot Peppers’ novel approach are a version of ‘Wake Up Little Suzy’, with an introduction of Chinese folk music, and the Beatles’ ‘Honey Pie’ with a chorus of the Charleston wedged in.”

in Hamilton the venue manager insistED the group stop playing as some punters had begun to dance

At Founders Theatre in Hamilton the venue manager came on stage mid-song to insist that the group stop playing as some punters had begun to dance in the aisles, contrary to house rules. Hans turned to him with his guitar and, without missing a note, backed him off the stage – a drop of about 10 feet – to the great approval of the audience. The group considered making this a regular part of its stage show, but the opportunity did not present itself again.

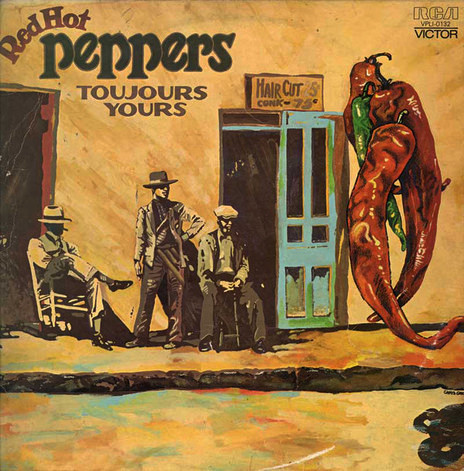

The tour coincided with the release of Toujours Yours, the Peppers’ first album. The group had secured a recording contract with PYE and Robbie had been writing material with recording in mind. To oversee production they enlisted Murray Grindlay, who Robbie had played with a decade earlier in Moses and the Munks, and who was now a successful jingle-maker and all-round studio pro.

Robbie: “Murray was laid back, encouraging and pleasant. I had hoped he could accentuate our blues and rock components. That didn’t quite work. My songs didn’t quite work either. No hits. Also PYE shut down in New Zealand in 1976. We ended up with RCA and the build-up hype was railroaded. But it made us a lot of friends, propelled the band along merrily, and got the industry interested so that we started playing more support concerts for overseas acts. Also Chris Grosz’s cover art was fabulous and has since become iconic.”

An Auckland Star profile of the band in late 1976 – probably written by Phil Gifford – described Marion Arts as having “an effortless, flowing voice” comparable to Sandy Denny. Toujours Yours, said the writer, needed some of the band's upbeat material. “But close listening pays high rewards, and the catchy reggae of Robbie’s ‘Dreams to Come’ opens the way to the less approachable material like the title song and ‘Let the Good In’, other Lavën songs which feature sudden changes of tempo.”

At the end of the national tour, Hans Lavën and Jim MacMillan amicably left the band. For a short period MacMillan was replaced by Div Vercoe, then Bruce Morley, while Bill Lake of The Windy City Strugglers came in on guitar. But, as Robbie says, “We were doing the same gigs, without the bright eyes. One of our last gigs was at the Mon Desir, the scene of former triumphs. Alas, management was snarky and [the manager’s] sister had parked her BMW blocking our truck. We dented it slightly and the furore and unbelievable repair bill we were asked to pay was so distasteful that we packed it in.”

At the end of 1976 Robbie and Marion left for Melbourne, enticed by former Mad Dogs member Pete Kershaw who was now living there, where they set about putting together a new Peppers line-up. An ad that read “Wanted: guitarist, must be able to play slow” brought them tasteful country-rocker Maurice Keegan. They recruited a local drummer, Vaughan Mayberry. The new-model Peppers was completed with the arrival of their New Zealand bass player, Paul Baxter. Robbie added didgeridoo to his arsenal of instruments.

But differences between the Australian and New Zealand music scenes quickly became apparent.

“Our niche in New Zealand was hippie, student, alternative lifestyle and female-friendly. Melbourne did not have such a niche. The Aussies were great, easy communicators without uptight attitudes to musicians. The first time we were on telly the bank manager came out to shake our hand.

“At some venues, like Bombay Rock in Melbourne, we created the same excitement as we did New Zealand and captured the imagination and emotions of the public in a similar way, but those moments were not common. But we slowly gained the same dedicated following as in New Zealand.”

The band acquired management, which was deemed essential for breaking into an industry “incestuously controlled by managers, pub owners, PA company magnates, truck-hiring companies, roadies, publicity agents and all.”

But management had its own ideas about how the band should sound and present itself. “Management wanted us to be like an international act. Marion was to be a chick singer who could be Australia’s Linda Ronstadt. Original songs were good because the manager’s mate the music publisher could get a cut and his recording studio owner mate could get a cut, and his record company mate could get a cut.”

And disco had arrived. Sometimes the Peppers were required to be the opening act for a DJ. Marion remembers “a certain member of the band snapping off the arm of a turntable as he walked by, in quiet protest.”

The roadies were good Aussie blokes WHO worked like Trojans, but weren‘t sensitive acoustic-music lovers

The sound could be a problem. Robbie says: “At rock gigs the roadies used to crank up the bass and bass drum so the public would dance. Marion‘s vocals could not be heard without her having to over sing and the acoustic instruments were a waste of time. The roadies were good Aussie blokes with names like Lurch and Shakes and Atlas. Dedicated and worked like Trojans. But not sensitive acoustic-music lovers.”

In spite of the difficulties, the Peppers were able to continue their recording career in Australia, with some pleasing results. Signed to a three-album deal with EMI, their first Australian release Bright Red came out in 1977. Robbie and Marion both regard it fondly.

“Recording Bright Red was a joyous and satisfying experience,” says Robbie. “No producer, the engineer was great, Marion’s songs were wonderful and the sound was strong and cohesive.”

Marion agrees. “The level of technical ability in recording was quite superior in Australia in those days. New Zealand efforts were lagging and had a less professional sound. But this new recording level was fun. Slick.”

The album gave the band a kickstart with regular television appearances and tours. Next came a soundtrack for a New Zealand feature film, Solo. “There were two producers,” says Robbie. “The New Zealand producer loved what we did. The cast came to concerts and particularly liked the delicate stuff, with sitar and modal moods. There was a lot of good feeling and respect.

“The Australian producer hated what we did. He could not wait to commission some forgettable muzak orchestral filler. And unbeknown to us, our manager and EMI did a shady deal with him to have the soundtrack paid for and released as the second of our three albums, with the muzak and all.”

The Red Hot Peppers went on to record one further album in Australia, Stargazing, released in February 1979. Though Robbie and Marion were happy with the original songs and the arrangements they had come up with, the recording process was fraught, largely due to friction with the English producer, John Wood, who had previously engineered records by Fairport Convention and The Incredible String Band: bands Robbie and Marion had admired.

Around the same time Robbie sacked the manager. “Instantly the Melbourne industry turned against us: gigs got cancelled, we weren’t paid for gigs because of supposed debts we had but did not know anything about, and bar owners who had always been pleased to have us were badmouthing us.”

They tried reinventing themselves as Marion Arts and Her Red Hot Peppers, adding keyboards and streamlining their instrumentation, with both Robbie and Marion sticking to guitars. Though this proved enjoyable for a while, money continued to be scarce. Eventually Robbie and Marion found work as a duo, and saved enough money to get to Europe.

Europe was an escape to regain sanity after the stress of Australia

“Europe was really an escape to regain sanity after the ridiculous stress of being full-time in Australia,” says Marion. “Healing and freedom was needed to recover our deep connection to our musical and personal authenticity.”

They worked as a duo, travelling, gigging and recording.

“Robbie and I had a great performing life there, especially doing festival concerts. The recording studios in The Netherlands were much better there as well. I wrote and recorded my best work in Europe.

“For myself, I think we should have gone straight to Europe. I would rather not have played in Australia, and would rather I had stayed away from its pop machinery, its bullying attempts at exacting simplicity, lack of depth. New Zealand was better for us.”

Eventually they returned to New Zealand, settling in Tauranga where they remain to this day. They have both continued to play, in a variety of settings.

Asked if they would do it all again, they wonder if there ever really was any choice.

“It sort of happened to us,” says Marion. “Our musical and creative urges were demanding an outlet. And we had faith in our combined artistic abilities.

“In short, we lived the dream, had a dedicated following that has not completely disappeared to this day, played some amazing concerts. We had not anticipated the negatives with our rose-coloured glasses. But we survived, when many didn’t. We did great concerts, touched upon fame if not fortune, and are happy to have been a tiny part of an unbelievably vibrant and adventurous period in the history of popular music.”

Marion Arts - vocals, saxophone, anklung, reso reso

Robbie Lavën - guitar, mandolin, saxophone, banjo, bousouki, violin, yang qin, lyre, sitar, Chinese flute, clarinet, flute, anklung

Hans Lavën - guitar, trumpet

Mike Farrell - guitar

Paul Baxter - bass

Jim MacMillan - drums, tambura, maracas

Maurice Keegan - guitar

Vaughan Mayberry - drums

Pete Kershaw - bass

Neil Reynolds - drums

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air