Civil’s roots lie in Rotorua. Her calling as a pianist, and especially a ballet accompanist, seems destined. Piano lessons started early at age seven as her nascent career as a ballet dancer was thwarted. “I went to the same piano teacher, Mrs Waters, for 10 years. I started piano because I had been kicked out of ballet at four,” says Civil, laughing. “I refused to stand behind any other child at the barre!”

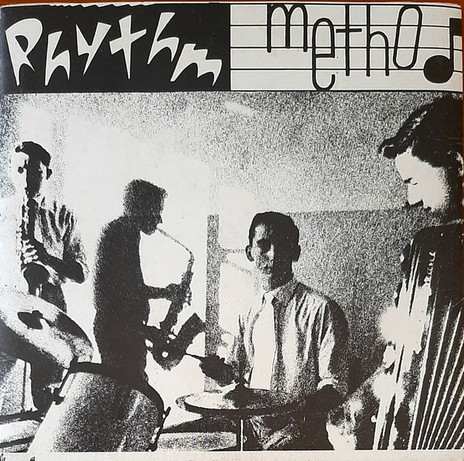

Ever the experimental artist, she started clarinet to get into the orchestra, but stopped as “you had to blow too much”. She gained entrance to the University of Auckland’s Conservatory of Music as a BA student in music, but was frustrated at the limited opportunities to practise there, as she was not a performance student. Her desire to perform led to joining Rhythm Method, something that coincided with finding a new circle, among Elam fine arts college students. “I got into the whole look of being a punk rocker ... I used to take my projects and university work in the fine arts library because I felt more with my people.”

For Civil, joining Rhythm Method (formerly Rare Device) in 1980 was huge. The band – Civil, Simon Mark-Brown, John Quigley, Dave Harris, and Bill McGechie (future comedian Willy de Wit) – first played at Mainstreet in Auckland. At the 1980 Battle of the Bands, Rhythm Method came second to Hattie and the Hotshots, and the band featured on the Hauraki Homegrown Eighty compilation with their song ‘Mad’, and the Class of 81 album with ‘Carousel’. An appearance at Sweetwaters followed in January 1981.

Changes to the line-up meant the end of the band was nigh: Mark-Brown departed, Phil Steel, who had drummed for Red Mole, arrived. But in November 1981 a self-titled EP was released with the songs ‘Got a Month’, ‘Creating Criminals’, and ‘High Street.’

Gill Civil, John Quigley, and Phil Steel became The Bongos, releasing ‘Monotony’ in 1982

By now only Civil, Quigley, and Steel remained, becoming The Bongos. They released the single ‘Monotony’ in 1982, with Civil on vocals, and their song ‘Nervous Tension’ featured on the 1982 Furtive Four 3 Piece Pack EP. The EP coincided with a tour of all four bands on the Furtive label: The Bongos (with new vocalist Brian Tipa), The Dabs, Skeptics, and Prime Movers. While ‘Monotony’ was reviewed in Rip It Up as “the radio song ... it’s a pity the melody lines aren’t stronger and the vocals better mixed,” ‘Nervous Tension’ was deemed by the magazine as “the most interesting” song on the EP. Post-tour, The Bongos played shows at The Windsor Castle in Auckland in August 1984 (released in 1985 as Windsor Bash) then took a new path.

In the early 1980s, British expatriate musician Ivan Zagni formed the Auckland collective Big Sideways as part of a government scheme for unemployed musicians. The revolving line-up included members of Blam Blam Blam and The Bongos. Quigley and Steel were keen to join as they liked the idea of incorporating brass instruments, but Civil wasn’t, as she liked their dynamic and could replicate those sounds on her keyboards. The energy in Big Sideways did not gel with her desire to write music. “The guys ... liked to roll up the occasional joint ... I just couldn’t, it was the whole energy of all those guys in a room.”

The days with Big Sideways included memorable moments, such as when she jammed with Japanese actor and composer Ryuchi Sakamoto (in Auckland to film Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence with David Bowie) who had heard about the Council scheme. “I didn’t really know how famous he was, he was just this really nice, humble [guy] ... basically he just wanted to hang out where the keyboards were, which was with me.” Sakamoto picked up on the different energies in Big Sideways. “He really gave me the idea that I should pull away from that situation, which I’m really glad that I did, because it took me in a whole different direction.”

As well as meeting Ryuchi Sakamoto, Civil also came across his co-star in Queen’s Arcade, gazing enigmatically into the window of a shop. “There’s this side profile ... I sort of stopped in my tracks, there’s nobody else around, and I’m thinking ‘he looks like Bowie’, and then I’m thinking ‘it is David Bowie’... look at him, he’s so tall and handsome. He was looking so sad because he’s all alone looking at some shop.” After deliberating on whether or not to go up to him and say hi, she decided against it and went on her way.

The building in Ponsonby where Big Sideways were based also housed Limbs’ dance studio, and one day Civil took matters into her own hands. She set up her keyboards in an adjacent room from the band, and found she could concentrate better. The song ‘Isol’ was written there, about isolation and simplicity. “I just wanted to find peace and some stability, something still in my swirly-whirly weirdo life of music.”

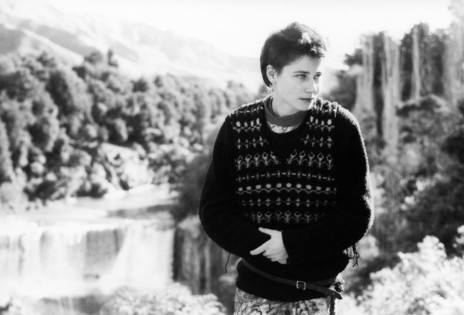

Ryuchi Sakamoto told Civil she should pull away from Big Sideways’ dynamic

The freedom to write in another space didn’t last – the following day Zagni fired her. This led to her working with Alan Clay, a professional street clown who taught Civil the mechanics of street performing. “He had me wear the red [nose], and taught me how to freeze ... that’s really, really demanding! It’s quite hard to do!”

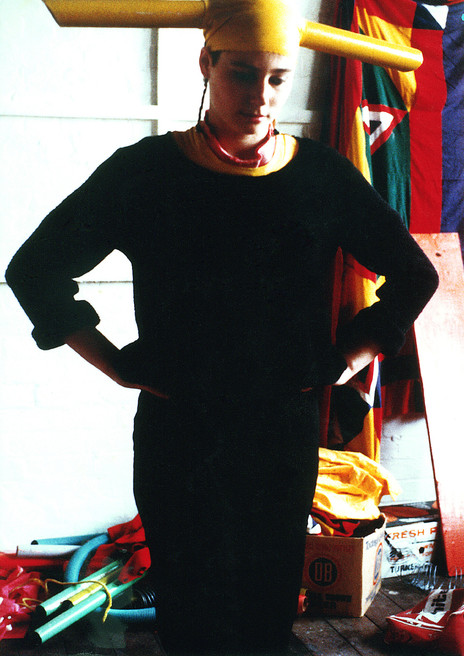

The double-clown act with Clay was short-lived and Civil was again looking for work. The Council suggested she perform alone on Vulcan Lane, and she created arresting street performances over the summer of 1982-83. Clad in blue face paint and sometimes with a headpiece made from yellow tubes, her performances were called (in no particular order) Yellow Tape Tubal Tone-Poem, Yello Yello, and The Third Human Minute.

Using electricity from Last Laugh Studio several flights of stairs above Vulcan Lane, these performances included musical elements. Civil created a background drone as a musical bed by taping down two notes on her keyboard, then putting them through a flanger. While playing she was posing and looking into the sky, holding the pose for as long as she could. The idea was to slow down time and movement, and performances could be lengthy.

“I was just like a sculpture in the middle of Vulcan Lane, but with a purpose. I had a microphone [and] I would say something like ‘Good morning, this is the BBC World Service. Here is the news in brief.’ That’s what I heard growing up as a child, and my father liked to listen to the news all the time.” She would continue with ‘Isol’. “I also had a synthesiser on top of the organ so I was able to play the bass and then I would sing this whole song. Then I would play some banjo.”

During that time, Civil struck up a friendship with Virginia Were, an art student who watched her perform and was very keen to join in. Initially experimenting with percussion as part of the performance, Were began playing electric guitar. As Matthew Goody observed in Needles and Plastic: Flying Nun Records 1981-1988, “although Were had little experience playing guitar, her willingness to experiment allowed the two to construct compositions that moved away from traditional pop structures in favour of atmospheric, fractured and experimental material.”

The pair performed over the summer then flatted together in downtown Auckland in a building of empty office spaces, surrounded by buildings in various states of demolition. Were soon introduced Civil to Sara Westwood, a fine-arts student and multi-instrumentalist. Westwood loved architecture, and was interested in the demolition sites surrounding their building. “We went into these half-demolished buildings with broken staircases, and she took pictures of everything. It inspired a song of mine called ‘Torch’, which was ‘the block lights up’ ... and then it’s ‘the blokes light up’ – I changed words, so you have a word and then it would morph into something that had a different meaning depending on how you said it.” Civil and Were called themselves Yello Yello, then Were coined the name Marie and the Atom.

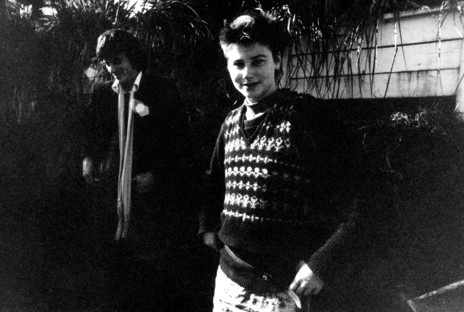

Marie and the Atom was the first all-female group to be released by Flying Nun

In existence from 1983 to 1985, Marie and the Atom was the first all-female group to be released by Flying Nun. Andrew Schmidt has written that they made adventurous music “that dealt with moods and rhythms which exist outside the usual space and gait of life.” (Read more about Marie and the Atom at the group’s profile on AudioCulture.)

A parallel strand of Civil’s performance career is accompanying ballet classes. Initially she played for Limbs Dance Studio between 1982-84, accompanying ballet classes on piano for instructors including Dorothea Ashbridge. Civil admitted to the Ballet Piano Podcast in 2022 that her first few times playing were challenging, as the instructors gave music direction in counts, and Civil hadn’t been trained in balletic language of timings.

She was determined not to play classical works, choosing instead to compose her own material. Her playing was in demand from international dancers too, including John McLachlan, a dancer with Merce Cunningham’s company coming in from New York. He was a fan of improvisation and wanted to be accompanied by Civil. She recalls that McLachlan “arrived at Limbs and they said ‘Oh we’ll get our proper pianist to play for you’. He said ‘No, I don’t want them, I want Gill Civil’.”

He had heard about Civil from Douglas Wright, who had danced for Limbs before heading to New York. McLachlan recommended she apply for a position as an accompanist at the Australian Ballet School. The audition was in Melbourne; on arrival she met up with some New Zealand friends and “... I just went and shaved all my hair off! Then I was trying to get to the audition and then the trams wouldn’t pick me up because I had a mohawk!”

She auditioned, but didn’t get the position. However, they recommended she try the Victorian College of the Arts. It was a good fit, as McLachlan was there. He asked her to contribute to a piece he was choreographing, and she performed with her new band, Barkers Eggs (Australian slang for dog shit), composing music on the school’s Fairlight CMI sampling synthesiser. She stayed with the College until 1988, apart from a brief sojourn touring with Crowded House.

“Ah. The Crowded House experience,” she says. For the band’s 1986 tour of Australia Civil joined them as their keyboardist, but did not continue. While opinions and rumours on this have circulated, Civil’s story is far more nuanced. “One morning I heard the radio announcer mention that Crowded House was embarking on an Australian tour and were in need of a keyboardist.”

Intrigued, she called the station to express her interest, and Neil Finn soon got in contact. Within a couple of days, she was jamming with Finn, Paul Hester, and Nick Seymour, and they clicked instantly. The audition was a success and led to a second rehearsal, where she landed the gig and was tasked with learning the band’s first album. Civil’s debut show with them at Mt Buller (eastern Victoria) coincided with the filming of the band’s video for ‘Now We’re Getting Somewhere’. She appears briefly, playing the melodica and keyboards on stage.

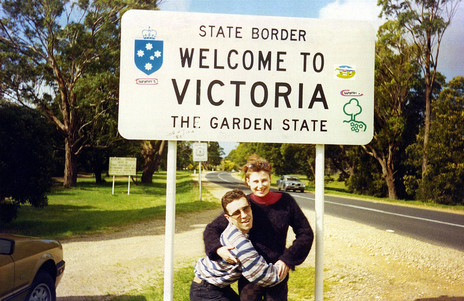

Touring with Crowded House was exhilarating but the glamour soon faded

Touring with Crowded House was exhilarating and they played sold-out shows to enthusiastic fans. Sharing the stage with the undoubtedly talented trio was exciting, and she could improvise before they came on stage, and they told her what key to end on before they started their set. While touring life had its moments, the glamour soon faded as ambition and managerial tactics took over, which led to miscommunication and some conflict. This started when Civil was asked to wear headphones on the car trip between Melbourne and Sydney to “study” the album. She says, “it soon became apparent this was a tactic to keep [me] from overhearing their conversations.”

Despite receiving favourable reviews from the press, Gill received minimal encouragement from the band during the road trip. They went as far as omitting her name during press conferences to avoid highlighting their female bandmate. Combined with not receiving a ‘per diem’, these challenges made life on the road quite difficult for her.

There were some bright points – amidst the difficulties, she fondly recalls the support of the roadies, who helped her financially when she endured days “confined to my hotel room, sustained only by instant coffee and a solitary croissant.” They also offered to transport her to gigs in the equipment van as they thought it would be less stressful than riding with Neil, Nick and Paul.

Finn later extended an apology for how the band treated her during the tour, and they remain friends to this day.

Back in Melbourne, Civil returned to the Victorian College of the Arts, and stayed until 1988 when she decided to travel. First stop: San Francisco, staying with David D’Ath (The Skeptics), and Sarah “Serum” Fort (Fetus Productions). After two weeks, Civil decided to venture further, and went to the Amtrak station and let fate decide her journey. Fate chose Canada, and she headed to British Columbia: first to Victoria, then Vancouver. While walking around the city she encountered professional dancers from Ballet BC, introduced herself to the teaching staff, and was consequently offered an audition with them and with Karen Jamieson’s Modern Dance Company. This was successful and Ballet BC offered her work.

Civil was invited back the next night to a performance which also proved fateful as she met her future husband, composer and musician Edwin Dolinski. While keen to stay, she returned to San Francisco as her Canadian tourist visa was short. Her return didn’t go smoothly, as she was mugged and her passport stolen. On receiving a new passport she went back to Canada as the experience had put her off the US. “I started working up here until I could no longer be here because I had gone around the border too many times getting the stamp, and they were going to deport me!”

Needing to leave, she returned to Australia (and to the Victorian College of the Arts) before quickly returning to Canada, working for the Simon Fraser University as a ballet and modern dance accompanist. Civil and Dolinski married, and she became a Canadian citizen.

Civil undertook a monumental task: writing a symphony about an Aboriginal legend

However, before leaving for Canada, Civil undertook a monumental task – writing a symphony about the legend of the Aboriginal warrior Yondi for the Victorian College of the Arts: Yondi found a stick to separate the sky and earth, waking up animals who had been sleeping. When Yondi threw away the stick, which had bent under the strain, it came back and was the first boomerang.

Initially a stand-alone piece for piano, Civil developed it into a 30-minute symphony for the entire college (orchestra, dancers, actors and artists) to perform. “I stayed up night and day for two weeks, I wrote the score for 26 different instruments. It was all in the shape of night and day ... the shape was a pattern on one of the boomerangs.” While the College loved the work, various circumstances meant the symphony wasn’t staged. Civil contemplated other vehicles for it, but the symphony remains unperformed, and will likely remain so due to cultural considerations.

Civil’s career in Canada since she returned has centred around ballet accompaniment, composition and performance, but in 1993 she contributed ‘Procession’ to the Flying Nun compilation Shrew’d, which marked the centennial of women’s suffrage in New Zealand. Civil and Dolinski are parents to two adult children who are both musicians: their son is a saxophonist, and their daughter the recording artist SIESKI.

In 2005 Civil recorded her first set of 28 ballet compositions for the first Dancing Keys album before releasing two further Dancing Keys albums of original tracks including ‘Aurora Australis’. Albums of pop music arranged for ballet followed, including Kompilation for Kids, a selection of ballet pieces including original works and pop song arrangements. In 2016 Civil had a career highlight when she performed with dancers at the International Dance Seminar in Brasilia. In 2009, ‘Isol’ re-emerged, this time as the opening and closing music for the New Zealand literary-focused television show The Good Word.

Civil continues to accompany ballet classes at the Simon Fraser University, Arts Umbrella, and Ballet BC, and is also in demand as an editor for music scores. Over 100 of her piano compositions are now represented by the New Zealand publisher Songbroker, and she hopes to publish a book of her work.

She and Dolinski are also film composers – in 2020 they wrote the score for The Man on the Island, a “character study” of long-time Rakino Island resident Colin McLaren, produced by her former Rhythm Method bandmate Simon Mark-Brown. Mark-Brown needed a score, and the couple had some unreleased piano material and “we were able to put the whole thing together pretty fast.”

After a music career spanning nearly 45 years she is considering future directions. “I really feel that I don’t want to be playing ballet classes anymore. I’m happy to write music for ballet, because I understand exactly what they want ... my most exciting time, apart from all the bands, was [writing] the symphony.” Things do come full circle.