A versatile musician, Zagni moved to New Zealand in 1980 with his New Zealand-born wife, and worked as a freelance musician, teacher, and composer. One of his first musical releases here was an EP in 1982 for Propeller called ‘Standards’, collaborating with Don McGlashan (Blam Blam Blam). He also played guitar on the track ‘Call for Help’ on Blam Blam Blam’s album Luxury Length.

Rip It Up’s Russell Brown wrote, in September 1983, “Zagni was asked to sort through the 40 or so musicians registered as unemployed in the city and select a number to form a group which would work and be paid for six months under a government PEP scheme.” His main criteria during the auditions were creativity and commitment.

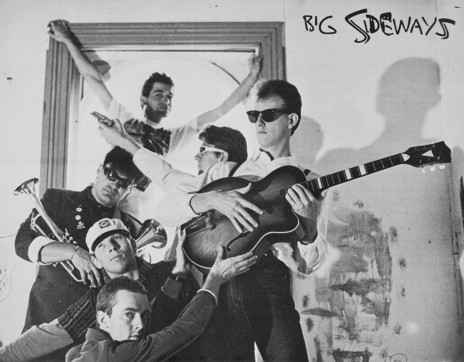

Zagni chose around a dozen musicians for the first intake under the scheme, from bands such as The Newmatics, Freudian Slips, The Bongos, Miltown Stowaways, Blam Blam Blam and others. They were Mark Bell (guitar), Jacqui Brooks (tenor sax), Scott Colhoun (trumpet), Chris Green (baritone sax), Paul Hewitt (drums/percussion), Brent “Syd” Pasley (guitar), John Quigley (guitar), Kelly Rogers (alto sax), Robbie Sinclair (bass), and Phil Steel (percussion). Gill Civil was also selected, but left after only a few rehearsals as it wasn't her style of music.

Zagni wanted experimentation. “When I arrived, I was staggered by the artistic potential of the place.”

They kicked into action in mid-1982, with Zagni wanting to focus on experimentation, noting that was made possible only because the musicians had a little financial security. “When I arrived in this country I was staggered by the artistic potential of the place. It’s a shame we’ve had to register as unemployed to finance this thing,” Zagni told the NZ Listener’s Bruce Gooding (June 11, 1983).

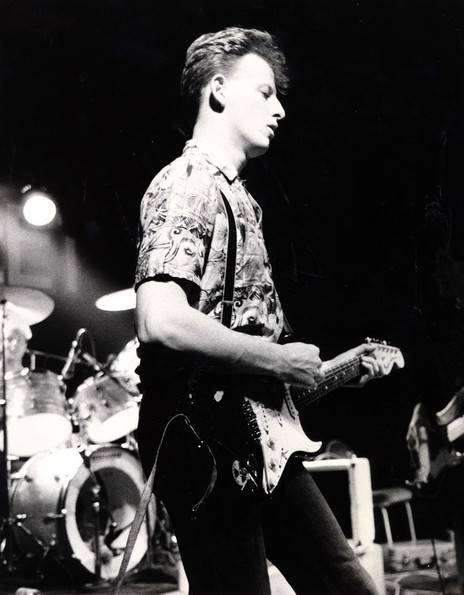

The group put together a set of originals over a few months and started performing around town. They met each day, working from 10 till 5, writing, rehearsing, and gigging. “People often said to me I should be stricter, but I’ve worked with musicians for many years and it’s very difficult to be that, you’ve got to be careful,” Zagni told Metro’s AnnLouise Martin (December 1982).

They stretched out beyond pubs, playing mostly at schools, retirement homes, parks, squares and IHC centres. They developed their sound to extend to acoustic performances as well, to suit those different spaces.

Big Sideways closed out the year as the scheme ended, with opening for Hunters and Collectors for two nights at Mainstreet in early November, and an album on the horizon.

At the conclusion of the six months, Zagni told Martin, “The musicians are coming out of themselves, their playing is much stronger. Since I’ve been in New Zealand, I’ve found the music excellent and the originality good, but it’s never come across as striking or strong in presence. The lyrics have tended to be a bit of a putdown – of politicians for example. People would rather hear other things and it’s beginning to change, which is a healthy sign.”

The scheme also aimed to give the band members knowledge around production techniques, recording contracts, and dealing with taxes. “Business knowledge is often forgotten, and it’s very much a part of being a survivor,” Zagni told Martin.

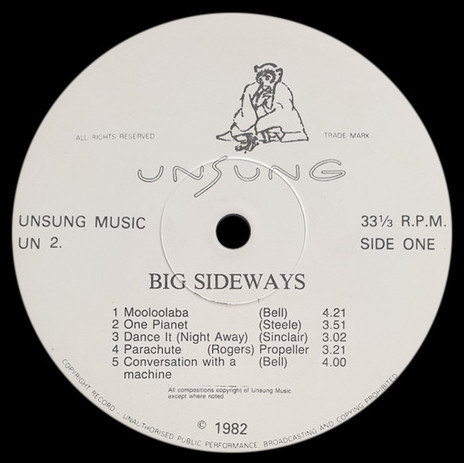

The creation of Big Sideways also led to the formation of a new record label, Unsung Music, to release their debut album, along with one by Robbie Sinclair, under the name Three Voices. The decision to start a label as an artist-run collective came out of a lack of interest from the majors.

The band was able to secure some funding towards the album from the Department of Internal Affairs, and ventured into Harlequin Studios during 1982, with new drummer Lee Connolly and the band producing.

The self-titled album emerged in early 1983 with cover artwork done by band member Jacqui Brooks. The 11-piece line-up played at Sweetwaters Festival ahead of the album release, with Rip It Up describing them as “A tailor-made festival band, these people made friends with their sheer size and energetic output. The music from 11 sources has now been fused in a common direction, a testimony to the hard work they’ve put in together. Songs from the new album due next month ... Let’s hope Big Sideways stay around.”

Rip It Up’s Duncan Campbell reviewed the album in April 1983, noting “The sound is horn-driven, with the four-piece brass section punching the colour into a largely funky base. The jazz leanings are strongly reminiscent of the more adventurous efforts made by Quincy Conserve in the late 1960s.”

A slimmed-down version of the band headed out on a national tour in June and July to promote the album, doing 24 shows. Most of the members who were involved during the PEP scheme had moved on. The core of Sinclair, Green, Connolly, Quigley, and Steel added Mike Russell (trumpet) and Sonya Waters (keyboards) to the line-up. The horn section of Green and Russell became known as The Newton Hoons.

However, Waters’ stint in Big Sideways was short-lived. She told Metro’s Annabelle Woodhouse (March 1984) she left as “I felt in that band that they did not consider me to be an equal to them. They’ve had three women in that band, and they’ve all left. Big Sideways held me back.” However she went on to work on her own EP soon after with support from some of the Sideways crew playing on it, along with Connolly engineering and Sinclair producing.

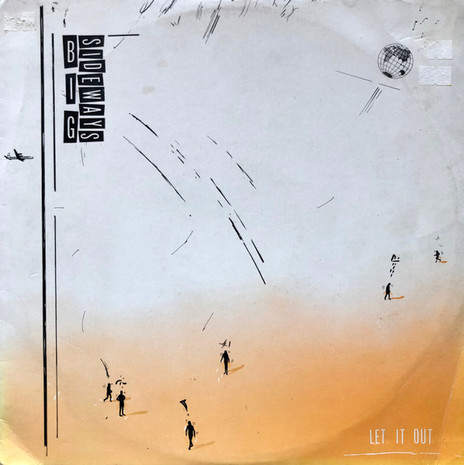

In September the band returned to Harlequin Studios to record a three-song EP, Let It Out. Backing vocals on the EP came from Betty-Anne Monga, Josie Rika, Graeme Gash, and Debbie Harwood, who had taken over as the band’s manager. Also contributing were Karen Hill on trombone and Tom Ludvigson on synth.

“People should be dragged by their toenails to see Big Sideways” –Mark Everton in ‘Rip It Up‘.

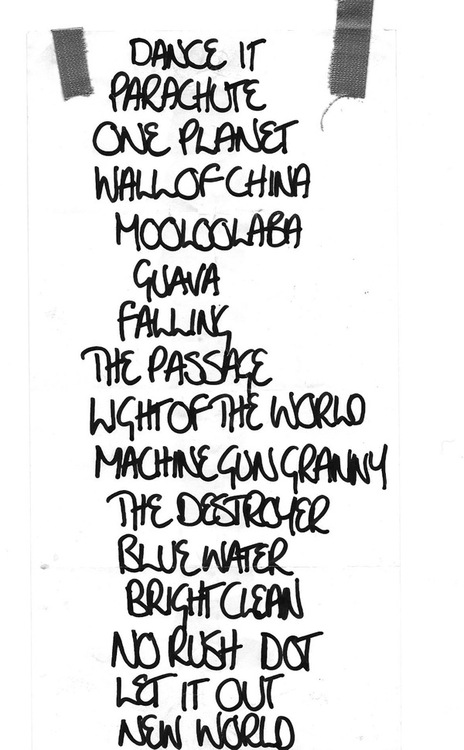

November 23 saw Big Sideways play at a Radio B fundraiser/end of broadcast gig, one of the last shows at Mainstreet before it closed. Rip It Up’s Mark Everton caught their set, writing, “People should be dragged by their toenails to see the Big Sideways band … the Sideways performed to a sparse Mainstreet with customary style and energy. Of the six new songs in the set the ballad-like ‘The Passage’ and the good-time ‘Blue Water’ stood out first time round. The three songs off the new Let It Out EP sounded even better live despite excellent production on vinyl.”

The Let It Out EP came out on Unsung Music in December 1983. In Metro, Chris Bourke described its sound as “cosmopolitan, but with dominating brass and percussion the feel is Latin American party time: Herb Alpert and James Last meet early Split Enz.”

The band closed out the year on the bill for a New Year’s Eve show at Mt Smart headlined by Split Enz, along with Herbs and Coconut Rough – the latter featuring two ex-members of Big Sideways, Mark Bell and Paul Hewitt.

But they were finding it tough making headway as they had started out with a reputation as a busking band, which meant breaking into the pub circuit wasn’t easy.

Steel recalls that Ryuichi Sakamoto of Yellow Magic Orchestra dropped into their rehearsal space under Limbs dance studio in Ponsonby, and invited the band to Japan, but no one seemed to click. He feels that was a pivotal moment and realised even though the band pushed the boundaries in some ways musically there was a huge streak of conservatism.

In May 1984 the new line-up of Big Sideways was featured in Rip It Up, adding Debbie and Justin Harwood (bass), and Tim Robinson (drums) with talk of a possible debut for this line-up: a Radio WIth Pictures special in June or July. There were also plans to get overseas.

However, a month later the Auckland Star reported the band’s demise. Big Sideways played their final shows at The Gluepot on 15 and 16 June, splitting due to pressures of turning from a work-scheme funded band to a professional touring outfit, along with some of the main songwriters, Connolly and Sinclair, having left the band.

Meanwhile, Zagni had been working with another band funded by the PEP scheme: Avant Garage.