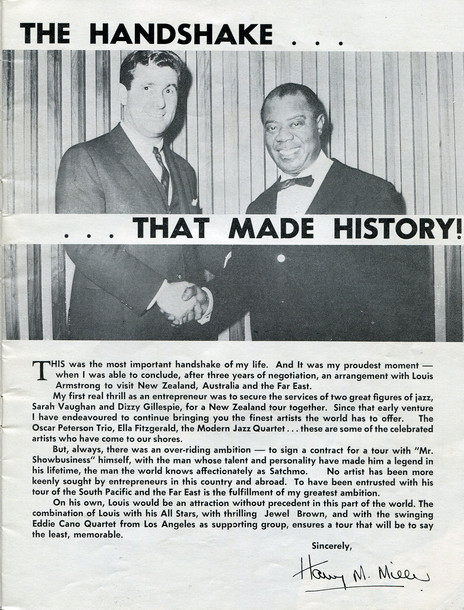

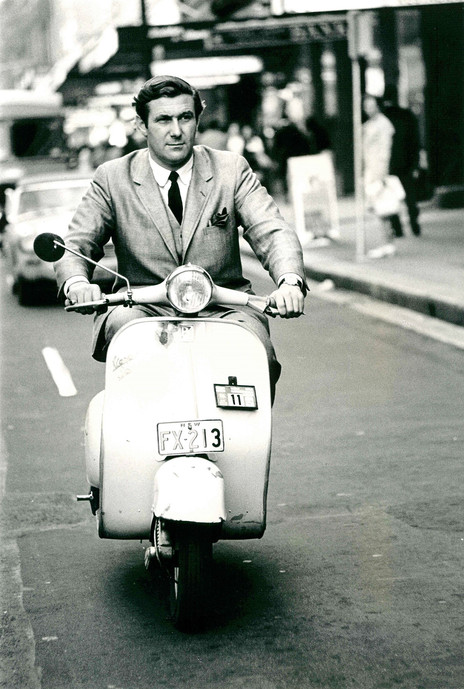

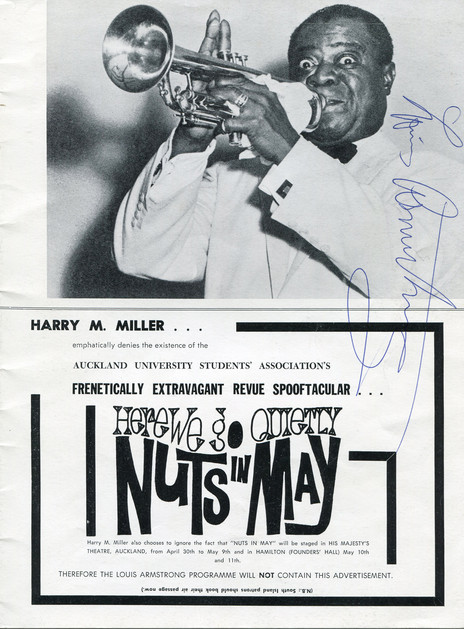

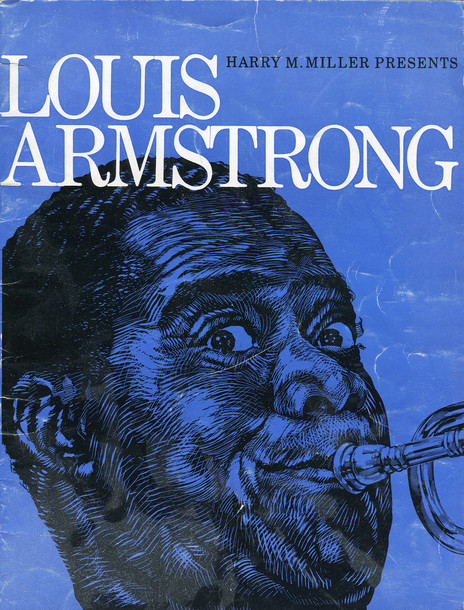

Harry M, as he became known, was the embodiment of chutzpah, the Yiddish word meaning cheek, audacity, and nerve. As a young man he honed his spiel selling electric cookers, socks, petticoats and men’s suits, then put it into practice, sweet-talking influential US and UK agents into allowing their top artists such as Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald and Dizzy Gillespie to tour downunder on the mere promise of success.

The promotional company he established in his early 20s grew into a showbiz giant after he moved from Auckland to Australia in the early 1960s, securing an impressive roll-call of international stars and touring full-scale proscenium-arch theatre shows throughout Australasia. He also spent 10 months behind bars on fraud charges after a business venture failed. But that was an unpleasant hiccup in an otherwise glittering career.

I was on Harry Miller’s payroll in the international casts of both Hair: The American Tribal Love Rock Musical and Jesus Christ Superstar in the early 1970s, but this is no personal tale. I was a bit player in his colourful empire and respected him as our distant producer and beneficent dictator, who dropped in periodically to praise us or rev us up, and appeared at the lavish season openers and closing night parties he threw. To all of us he was simply “Harry”.

Harry Maurice Miller’s childhood in Grey Lynn, Auckland, was miserable. His immigrant Jewish parents from England, Sarah ‘Sadie’ and James Miller married in the Auckland Synagogue at the beginning of the Depression. They had a stillborn daughter not long after. Harry was born on January 6, 1934, the year that Hitler declared himself Führer in Germany.

As a child he charged friends to view the peep-show he created in a shoebox.

In his two autobiographies (both authored with ghost writers) Harry writes that Sadie whinged constantly about her woes and that he copped it all, including beltings, when his father died young after a lingering work injury.

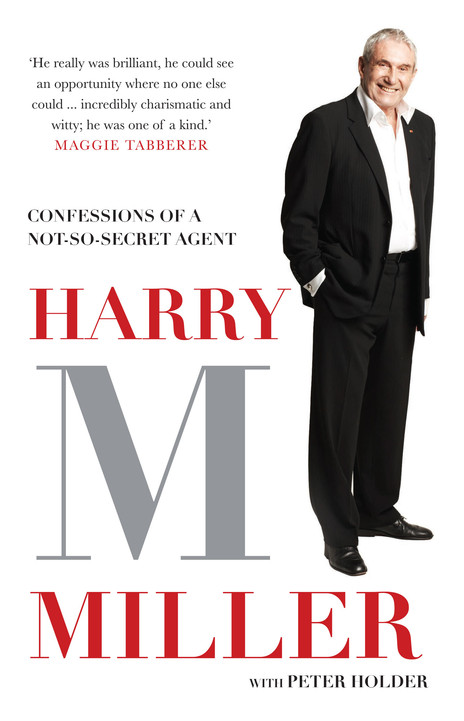

“A nice platform of misery had been laid, one could suggest, before I took my first breath,” he wrote in Harry M. Miller: Confessions of a Not-so-secret Agent [with Peter Holder, Hachette, 2009].

His parents’ Judaism made little impression on him growing up, despite having to read in Hebrew from the Torah every Friday for his mother, and Harry couldn’t wait to be grown up and out of there. Early on he had an inkling that being a self-made man with independent income would enable him to do so.

At Auckland’s Richmond Road Primary School, he charged friends marbles to view the peep-show diorama he created in a shoebox. Then at nine, when Sadie shipped him off for a while to a Jewish boarding school in Wellington, he practised early hawker skills as a lolly boy at Athletic Park.

Harry attended both Rongotai College in Wellington and Auckland’s Mount Albert Grammar School, but dropped out before taking School Certificate. He was an above-average student, but the boredom wore him down.

At 15 he worked on a Ngatea farm, where got a taste of life on the land and an insight into the solid work ethic involved. Coupled with his native determination, this served him well in the years ahead. Then, at 17, he joined the merchant navy on the Monowai – a recommissioned troop ship plying the Auckland-Sydney route – working as bathroom steward, “Captain’s Tiger” (serving the Captain’s table) and ship’s printer. Sydney stopovers opened his eyes to big-city life and sparked his desire for more of it.

Back in Auckland he did a night-time management course, then took a job at Holeproof selling nylon socks before following Holeproof’s sales manager to the Silknit factory, where he learned business skills about undergarments from the grass roots up – packing, cutting, and advertising product, including organising an in-store petticoat parade with ballet dancers from a touring production of, ironically, Peep Show, in a real-life echo of his earliest enterprise.

After hours he frequented music venues such as Lou Mati’s Polynesian Club. “One night, inspired by reckless confidence in my sense of rhythm, I asked a drummer I knew if I could sit in for him during a simple set,” he writes in his first book, Harry M. Miller: My Story [with Denis O’Brien, Macmillan, 1983]. This led to occasional fill-in gigs, and he also risked the odd turn behind the mic for a spot of speak-singing à la Rex Harrison in My Fair Lady.

Harry waited tables, cooked and, to impress a girl, even took ballet lessons.

Harry moonlighted waiting tables, short-order cooking in a Hungarian restaurant and, to impress a girl, even took ballet lessons. Knowledge gained in this stint in the pas de deux world came in handy later when he was marketing Ballet in Education records.

Harry’s repeated flirtations with restaurants through the years – including La Bohème on Wellesley Street West and the continental-style Henry the IV upstairs in Queen Street – proved that catering was not his natural milieu, but he kept trying. He was maître d’ and self-styled “king of flambés“ at Henry the IV and in a last-ditch attempt to attract custom as it slid into the red he spruiked its attractions at a rotisserie-chicken stand at the Auckland Show.

In 1957, he married his first wife, Zoe, and their son, Simon, was born in a hurry in their Northcote home a year later, delivered by their doctor neighbour. Together he and Zoe opened a fashion boutique, but when this folded and he hit the bottom they moved in with Zoe’s mother.

Harry seagulled on the wharves till he spotted a salesman-wanted ad at Electrosheet Metals to sell their electric frying-pan forerunner, the Electromet Cooker. He brought his nascent sales-and-promotion skills to this product, became its sole franchisee, and demonstrated its efficacy in stores and at food fairs. The franchise helped keep his wallet topped through the founding years of Miller Associates Ltd, which he began aged just 23.

Another rag-trade job appeared when he met Eric Barlow, who was marketing Australian-made Anthony Squires suits. Together they worked out a pitch to generate news, convince Kiwi blokes they needed at least one well-cut suit, and move as many units as possible. “With my Zealon socks and hoop-la petticoat apprenticeship behind me this new challenge was something of a snack,” he wrote [My Story].

The pair put on presentations in upmarket hotels and invited business leaders, VIPs, retail leaders and the press, and laid on drinks, food and entertainment in the form of Harry and Eric doing a comedic song-and-dance routine. The news circulated, suit sells soared and Anthony Squires became a well-known brand.

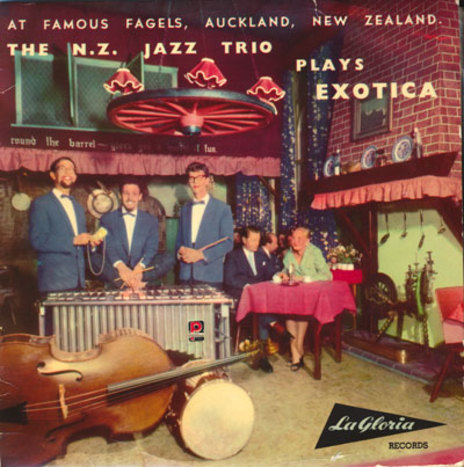

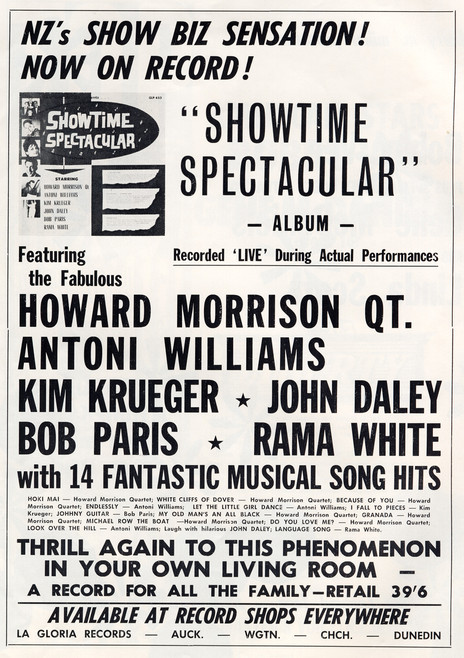

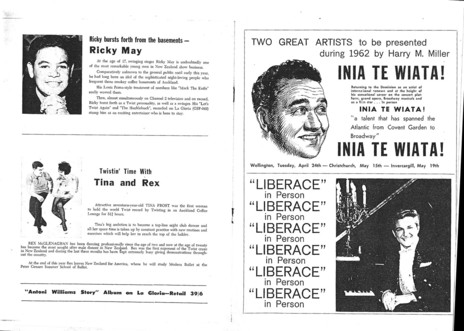

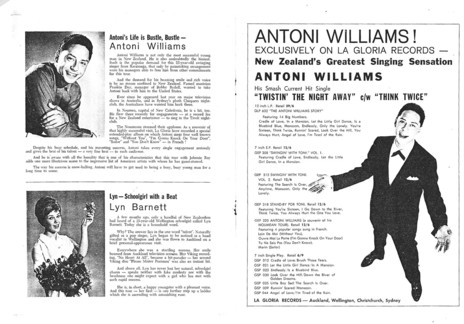

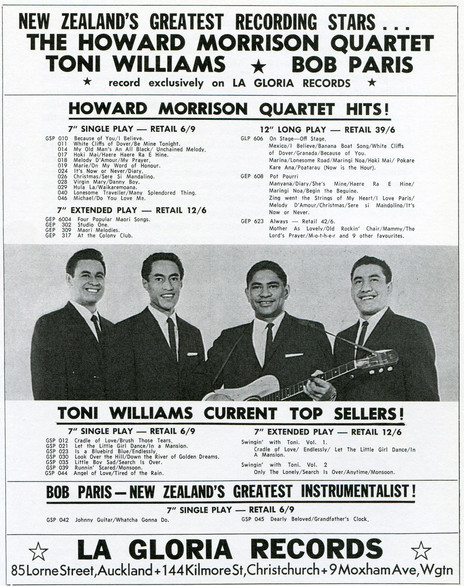

Harry’s business was on the up by the late 1950s and Festival Records, Australia approached him to promote them. He decided there was money to be made in records and instead created his own label, naming it La Gloria after a range of radios and record players made by Kiwi company Dominion Radio and Electrical Corporation. The more successful La Gloria was, the happier Dominion was to get the reflected shine.

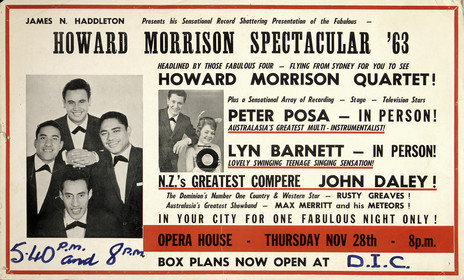

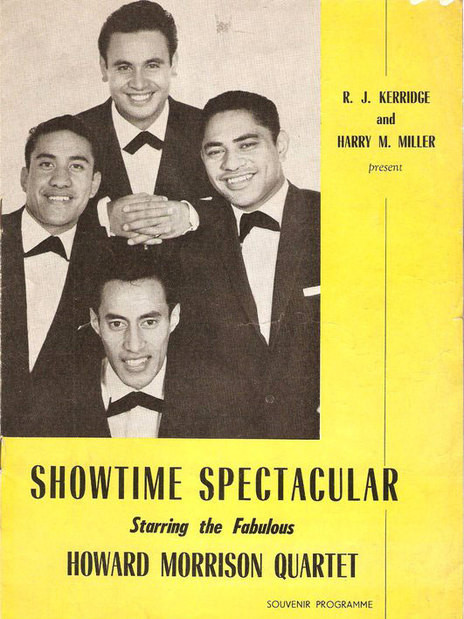

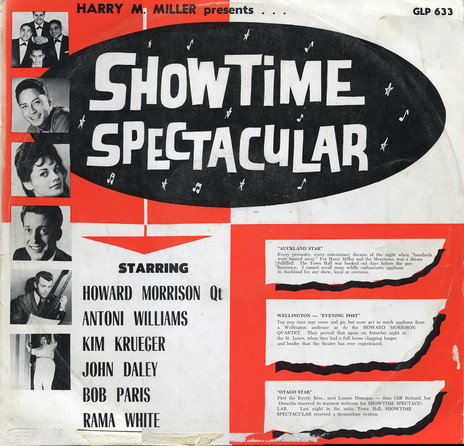

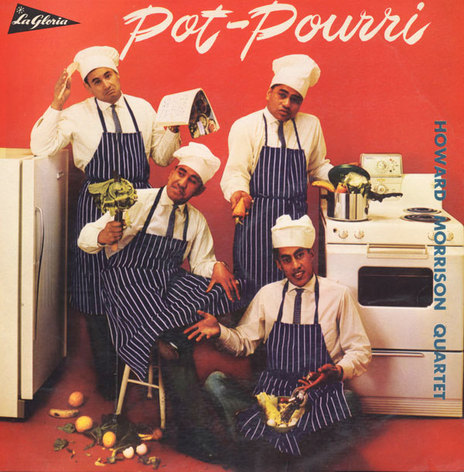

He launched La Gloria with two American motivational records, and then cast around for suitable local candidates to record. At the time, the Howard Morrison Quartet – Howard Morrison, Noel Kingi, Gerry Merito and Wi Wharekura – was the most popular act of the day. Harry’s former Hebrew School contemporary, promoter Benny Levin had discovered them, but Harry offered them a top-price deal and they accepted. The manoeuvre became a seminal career milestone for them both.

“Morrison recalled that ‘Harry was plausible, very plausible. He was also an intimidating bugger; he’d come right up to your nose to talk to you. But the man couldn’t be denied,’” wrote John Costello in Howard, the memoir of Howard Morrison (Moa Beckett, 1992).

Harry promised the Quartet top dollar for their concerts and gigs, then ferried them to all points to make it happen. He also polished their presentation by dressing them – and himself – in sharp Anthony Squires suits. At the same time, the advent of television in New Zealand in 1960 had begun sucking the life out of cinema. The Kerridge-Odeon chain was suffering. Harry hatched a plan to stage a nationally touring variety-show production and offered Robert Kerridge a double deal with naming rights, based on Kerridge supplying the theatres and Harry supplying the artists. He also had the National Film Unit filming the Quartet in concert so that the cinemas could use them as shorts.

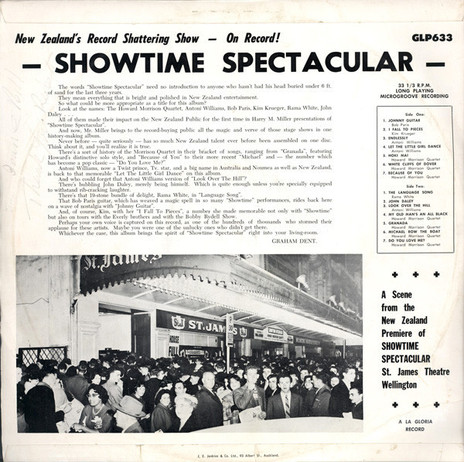

This was the basis of his bankable Showtime Spectacular tours, with the Quartet as headliners and a rotating bill of artists. The format paid dividends. The first lineup launched at the St James in Wellington and Harry was aglow: “The nerves in my spine tingled as I stood at the back of the theatre and absorbed the fact that I had created a hit show. I had created a hit show – my first.” [My Story]

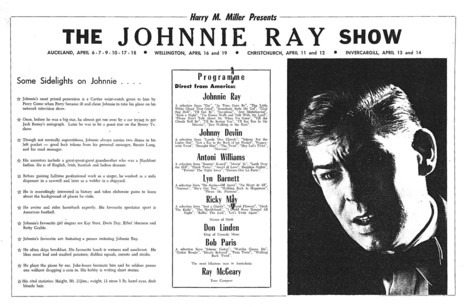

The first iteration of Showtime Spectacular toured for 19 sell-out weeks and featured Rarotonga’s Toni Williams, Australian singer Patti Brittain, Māori vocalist Rama White, female impersonator Noel McKay, and blind virtuoso pianist/saxophonist Claude Papesch. Reprised over the following two years, the show was equally successful. Previous to these tours, still only 25, Harry had toured Aussie rock’n’roller Johnny O’Keefe to poor houses, but Showtime kept his pockets lined.

‘My Old Man’s An All Black’ became an instant and enduring crowd favourite.

While on tour the Howard Morrison Quartet and Harry cooked up a parody to Lonnie Donegan’s ‘My Old Man’s A Dustman’ in a sly and timely dig at the controversy over the selection of an all-white All Blacks side to tour South Africa. Recorded live for La Gloria in a Pukekohe theatre after a Showtime concert, ‘My Old Man’s An All Black’ became an instant and enduring crowd favourite.

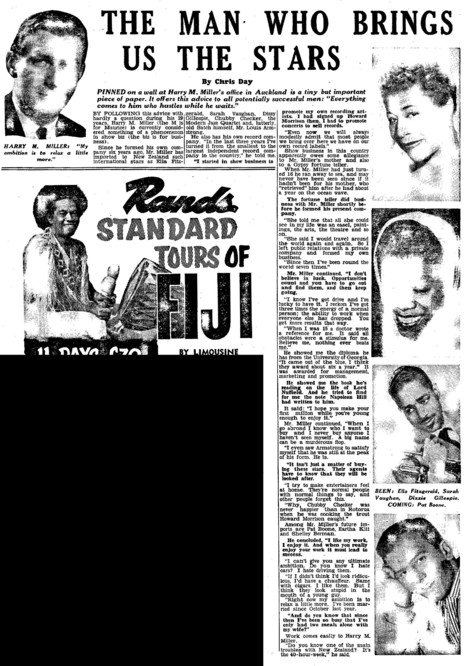

Harry began casting his net further. In Los Angeles he secured New Zealand rights for US labels Reprise, Roulette and Cameo Parkway, and this put him in touch with some of their artists. He started handling the New Zealand end of tours for Australia-based American promoter Lee Gordon, selecting top acts from Gordon’s multi-artist shows. He picked Sarah Vaughan and bebop maestro Dizzy Gillespie first and announced the show as “New Zealand’s first annual Festival of Jazz, 1960”. Miss Vaughan was gracious but Dizzy was, in his words, “an unmitigated pain”.

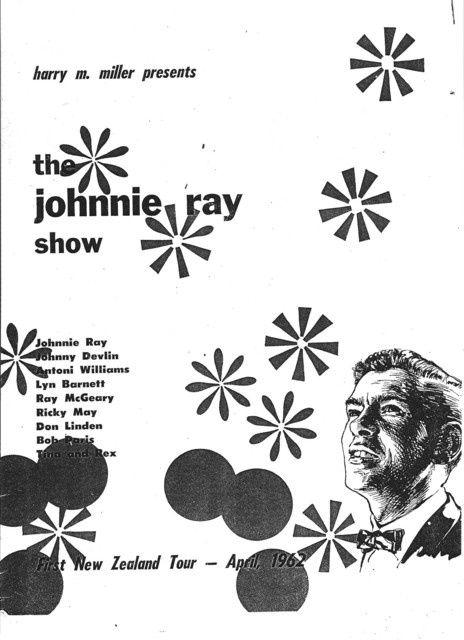

From 1961-63 Harry promoted some 25 tours across Australasia, all the time expanding his craft with shop-window displays, radio ads, press exposure, write-in and dine-with-the-star competitions in magazines and newspapers, special-offer records of his touring acts, and even mixing the glue for concert posters and sticking them up himself. Not much fazed him.

He was unsuccessful in gaining representation of cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin and his spacecraft for a world tour, but did secure many top artists to tour New Zealand either solo or on a shared bill. They included Bobby Vee, Connie Francis, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Bobby Rydell, Gene McDaniels, Del (“Runaway”) Shannon, Jimmie Rodgers, the Everly Brothers, Gene Pitney, Bobby Vinton, Irish singer Patrick O’Hagan (very successful), an Irish package production (disastrous), Chubby Checker, and an odd comedic psychology act by US Dr Murray Banks, whose ill-considered statements about a New Zealander led to a court case for slander and an out-of-court settlement.

Miller Associates Ltd was expanding and Harry moved to bigger offices in Lorne Street, Auckland and took on two staff, including former seminary student Anthony Hollows, who stayed with him for 15 years and became a close friend. Harry was busy, working and making money, even as his marriage was failing.

“By 1962, my marriage to Zoe was about to end in divorce, the first of several relationships in my life to falter due to my workaholic and extra-curricular ways [Confessions…].”

Harry agreed to partner promoter and friend Bruce Gordon on an Australasian tour of the Kingston Trio. Sadly, the trio’s moment in the sun on the back of ‘Tom Dooley’ had faded and the tour bombed, but the exercise made Harry realise his obvious next step was a move across the Tasman. Miller Associates Ltd was now a recognised identity and he had forged solid connections with key overseas agents. He and the Howard Morrison Quartet had gone their separate ways and, in 1963, Harry took the plunge, leaving the family and moving to Sydney.

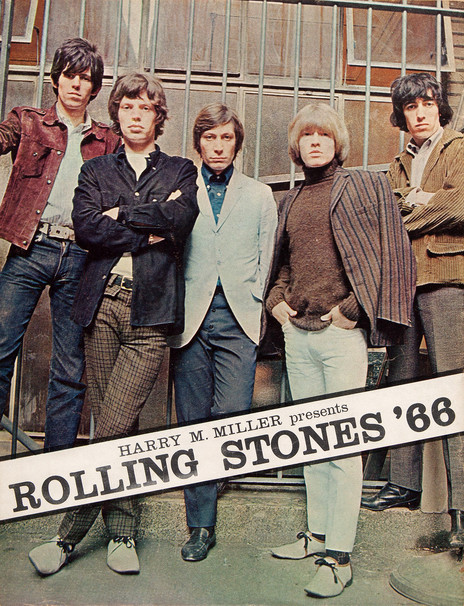

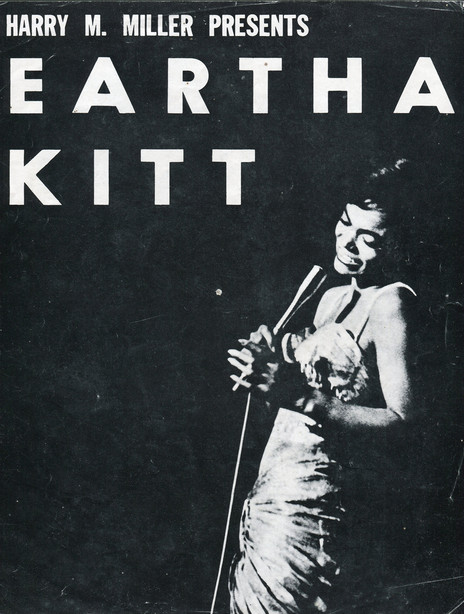

US agent Sol Shapiro had introduced Harry to Sydney’s Wong Brothers, who owned Chequers nightclub – the city’s premier cabaret venue – and with them he set up Pan Pacific Promotions. This partnership was long and fruitful, bringing in such major stars of the day as Liza Minnelli, Dusty Springfield, Sammy Davis Jr, the Rolling Stones, Roy Orbison, Shirley Bassey and the troubled star of stars: Judy Garland.

By now he had remarried, meeting his second wife, Patricia Mitchell, in New York at a Mickey Rooney Thanksgiving party. He had also added the “M” to his signature to differentiate himself from the Harry Miller who ran Sydney Stadium.

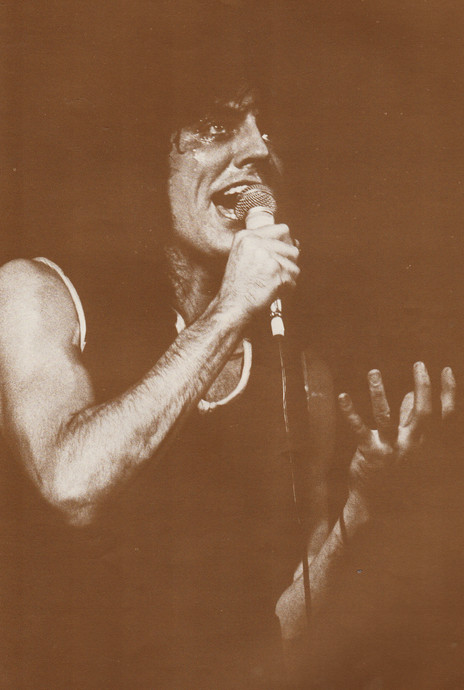

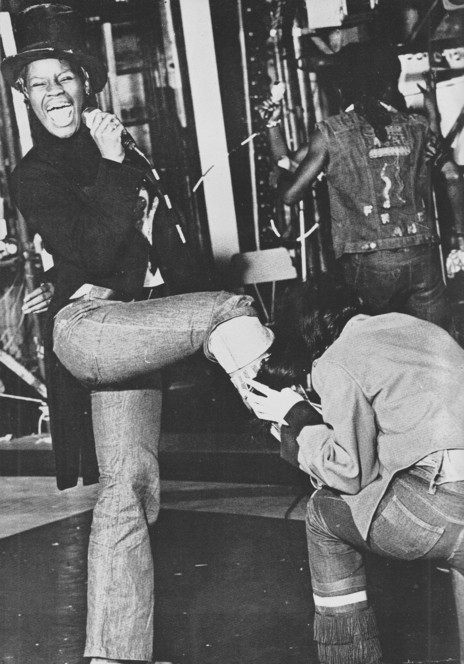

His move to Australia was not the end of his New Zealand operations by any means. If anything, his influence here grew exponentially stronger when he recognised the entertainment potential of a new phenomenon, the rock opera. He secured the rights for the counter-culture rock musical, Hair, hired an innovative production team, and cast it with performers from the US (including 16-year-old Marcia Hines, to whom he was guardian till her majority), the UK, Australia and later New Zealand. After sell-out 1969 seasons in Sydney and Melbourne he toured a full-scale production to main cities in New Zealand and Australia, then followed these with Jesus Christ Superstar (1972-4 in Australia, 1975 in New Zealand) and the Rocky Horror Show (1978 in New Zealand).

Each of these shows had an edge and drew horror or disdain among the more puritanical or closed-off elements in society for their morally confronting, perceived antisocial or religious themes. In New Zealand, the publicity could not have been better for the Auckland season of Hair when various self-proclaimed arbiters of acceptable morality took him and the show to court for obscenity. Harry won the ensuing three-day trial and the publicity extended the original run of the show by several weeks.

“I don’t know what the formula for success is, but the formula to failure is to try and please everybody,” he later said, in 1990 Australian TV documentary The Grass is Greener.

After stepping back from shows Harry bought Dunmore, an 11,000 acre property near Tamworth in New South Wales. With third wife Wendy Lapointe, a vet, he established an award-winning herd using Simmental breeding stock imported from New Zealand. At one time the property was the largest producer of Simmental-registered stock in Australasia. By now he was focusing on celebrity representation, with a client list that included former Australian prime ministers Gough Whitlam and Sir John Gorton; Whitlam’s nemesis, former Australian Governor-General Sir John Kerr; Lindy [A Dingo’s Got My Baby] Chamberlain-Creighton; Graham “Galloping Gourmet” Kerr; publisher Ita Buttrose, and media personalities. He was also busy on many boards and societies, including Qantas and the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

A 1977 career highlight came with a royal imprimatur when Harry produced the lauded celebrations for Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee in Australia; he spent time at Buckingham Palace and liaised with a young Prince Charles, whose company he enjoyed.

The following year was also spent at Her Majesty’s pleasure. To borrow the Queen’s own phrase – 1978 was Harry’s annus horribilis. In what he would look back on as both a prescient move in light of today’s digital focus and an enormous mistake, he founded a computer-based ticketing business, Computicket. This lasted just six months before going into receivership and, given a sentence of three years in what Harry always believed was a miscarriage of justice, he spent 10 months in jail for fraudulent misappropriation of funds.

The showbiz world is full of rapturous highs, nail-biting lows, outlandish behaviour and unexpected ecstasy.

The showbiz world is full of rapturous highs, nail-biting lows, outlandish behaviour and unexpected ecstasy. From petticoats to princes, prison overalls to prize cattle, Harry rode the waves and came out bruised but laughing. For someone so sharp and canny, it was cruel irony that he spent his last years in care after a 2011 dementia diagnosis. By his own admission he was a serial philanderer and had had liaisons with many beautiful women, including wives, partners and stars, such as Shirley Bassey. But he had also yearned for family and his two sons and three daughters to three different women, all remain close. He died in Sydney aged 84 on July 4, 2018 surrounded by family.

Harry grew up in New Zealand and operated largely in the southern hemisphere, but unconstrained by provincialism he was never afraid to go out into the world to pursue what he wanted, and his success played a major role in opening up Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific basin to international entertainment.

Black and white Harry’s life wasn’t. A “Jewish self-promoter”, in his own words, he lived life in full technicolour. Producer to the nth degree, he had planned his own farewell years before as “the best bloody memorial I have ever been to in my life!”. As befitting the departed showman, it was an all-star affair at the Capitol Theatre, where Harry had originally staged Jesus Christ Superstar, with performances led by Marcia Hines singing ‘I Don’t Know How to Love Him’ and heartfelt speechmaking. Promoter, producer, deal-maker, impresario – Harry M-for-Maurice Miller talked a big game and delivered to the end, exclamation mark.

--

Editorial note: Harry Miller’s description of his relationships with women was put in a different light in 2021 with the publication of activist and politician Sue Kedgley’s memoir Fifty Years as a Feminist. She describes Miller, “then at the height of his power”, setting up a hotel meeting with her in 1972, after which he committed a sexual assault and attempted rape. Kedgley decided against reporting the attack at the time.