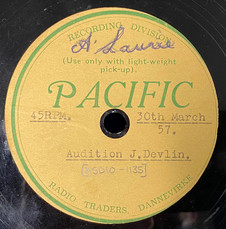

A rock’n’roll relic arrived at the Alexander Turnbull Library in late 2021: Johnny Devlin’s first recording. The 8-inch lacquer disc has the generic label of the Pacific recording studio in Dannevirke, southern Hawke’s Bay. Typed on the label are the details of the session: an audition with J Devlin, 30th March 57. Hand-written is the name of its original owner, A [Arthur] Laurie, the drummer of the local trio which played on the session. The other members are listed on the B-side: Arthur’s son, saxophonist C [Colin] Laurie and, on piano, E King.

Johnny Devlin's audition on 8-inch lacquer disc, 30 March 1957. - Archive of NZ Music, Alexander Turnbull Library

In early 1957, a year before he went to Auckland, Devlin was going places fast in the lower North Island. He had grown up in a Whanganui family that enjoyed singalongs, and got his first guitar at the age of 11. He mostly played country and western, and made his debut at the local opera house singing ‘She Taught Me How To Yodel’. With three brothers and a cousin, he formed the River City Ramblers, a skiffle band. Devlin’s father would drive them to talent quests and charity shows, from Taranaki to Horowhenua.

He was determined. Whenever any acts came through Whanganui, he would step up and offer to sing an item. Among the high-profile bandleaders who remember the teenager approaching them were Benny Levin, Colin King, Johnny Cooper, and Tommy Kahi. Once Devlin heard Bill Haley’s ‘Rock Around the Clock’ on the Lever Hit Parade, he became a dedicated rock’n’roller.

He bought a motorbike on tick, and roamed the district, looking for music and opportunities. In Palmerston North he hung around the Square with fellow milkbar cowboys and play the jukeboxes. His first paying gig was at the Swing and Sway Club in Napier; he cruised over from Whanganui on his motorbike with a guitar slung across his back, earning 10 shillings for his trouble.

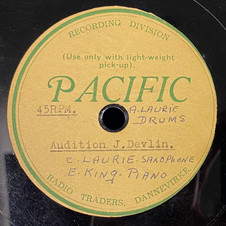

Johnny Devlin's audition disc, side two, 30 March 1957. - Archive of NZ Music, Alexander Turnbull Library

Devlin entered a talent quest in Dannevirke and – despite having one arm in plaster for a severed tendon – won the £75 first prize. On Saturday 30 March 1957, five days after a “Rock’n’Roll Jazz Concert” in the Palmerston North Opera House, promoted by Don Richardson, he entered the Dannevirke studio of Ivan Tidswell, ready to rock.

But he wasn’t quite ready. “Where’s your band?” said the studio engineer. Devlin didn’t have one so some local musicians were hired: the Laurie father and son, and King. They quickly recorded three numbers: ‘Shake Rattle and Roll’, made famous by Bill Haley; ‘River City Rock’, which is thought to be a Devlin original; and ‘Why Don’t You Believe Me’, a much-covered song that was a No.1 US hit for Joni James in 1952.

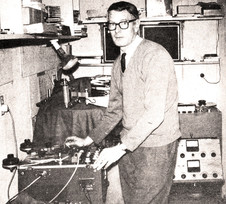

Locals remember that Tidswell often recorded acts in the Dannevirke Town Hall; two that have been mentioned are the Zeros and the Transonics. Six months before the Devlin session, at his home studio on Swinburne Street, he recorded Manawatu country duo Rex and Noelene Franklin for their debut on Tanza. Tidswell had become interested in recording while in the RNZAF, and from 1950 – anticipating the demise of “authentic Māori music” with urban migration – began recording concert parties, school groups, and Māori singers. “There has always been a fantastic amount of Polynesian music in and around Dannevirke,” he said in 1969. (By the late 1960s Tidswell was traveling around the Pacific with his portable equipment, recording village groups and hotel entertainers.)

Ivan Tidswell, 12 years after recording the Johnny Devlin audition.

The Devlin Dannevirke sessions sound like they were recorded in a hall rather than a small room. The saxophone is well back, and you can hear the space in the way the drums and piano resonate. Devlin’s rhythm guitar and King’s piano are only just audible for extra rhythm. Devlin’s singing is exuberant, but tentative compared to what he would be capable of a year later. On the ballad ‘Why Don’t You Believe Me’ he has pitch issues. ‘River City Rock’ is the work of a fledgling writer, to the standard rockabilly template.

Well I was walking down the avenue late one night

The juke-a-box jumping with all its might

I went into the milkbar to take a seat

Before I could move, I was rocked off my feet

The river city rock, the river city rock’n’roll beat …

Does “the avenue” refer to Whanganui’s main street, Victoria Avenue? If it can be confirmed that ‘River City Rock’ is written by Devlin, it can take its place beside two other pioneering New Zealand rock’n’roll originals recorded within months of each other in 1957: ‘Resuscitation Rock’ by Sandy Tansley, recorded in February, release date unknown; and Johnny Cooper’s ‘Pie Cart Rock’n’Roll’, released in October. (It was a Whanganui pie cart that inspired Cooper’s song; he wanted a “free feed” after a charity gig in the city, so offered to write the cart a song. Although years later, the proprietors – in a romance-free comment – denied they ever gave any food away, Victoria Avenue is becoming ground-zero of New Zealand rock’n’roll songwriting.)

At the Alexander Turnbull Library, senior audio-visual conservator Bronwyn Officer says it was a “particularly exciting” moment when the 8-inch disc was received from ATL’s Archive of New Zealand Music. Her job was to make a digital copy of the disc, before any further deterioration occurred, and to make a listening copy available to library visitors. Luckily, it was a cellulose nitrate disc – a lacquer – on an aluminium base, in very good condition. (Lacquer discs are often erroneously called acetates.)

She recorded the disc the first time it was played on the library’s turntable, after setting the equalization curve to the RIAA standard set in 1955. “That means when you cut the disc the equalization matches how it was recorded. Using a spectrum analyser – a visual display across the frequencies – you can see how the frequencies are distributed. Just as silent films are often seen sped up because they’re played back on incorrect equipment, having the wrong EQ can mean there is no bass, say, or the treble has gone.”

Devlin’s Dannevirke session is a seminal recording in New Zealand’s rock’n’roll history.

The Devlin recording, says Officer, sounds like it was made using two microphones: one for the vocals and the musicians on the other. “It was great to hear it, warts and all, that’s what I love about it. It’s an audition after all. It was very exciting, and to see all the information on the label. That information is very useful as we transfer the disc. I might have one more go with it, and give it a gentle clean. It’s intact. You’d never attempt to put water on it if it was delaminating.”

Devlin’s Dannevirke session is a seminal recording in New Zealand’s rock’n’roll history, and is now safe in the Archive of New Zealand Music. Eighteen months later, Devlin was barnstorming his way up and down New Zealand on a national tour that lasted six months. So it was a wonderful surprise when, while preparing a Radio New Zealand programme on which the Dannevirke disc would make its broadcasting premiere, archivist Grant Gillanders let me know he had a tape of another key moment in Devlin’s career. While checking a reel-to-reel tape he had been given, to see if it included anything of interest, he had all-but given up when four songs by Devlin appeared towards the end.

The four songs are from another landmark rock’n’roll moment: a recording of Devlin performing live in a Christchurch concert during his notorious 1958-59 national tour. The crowd is already fired up when Devlin is introduced for his first number, Freddie Bell’s ‘Gonna Teach You to Rock’. The energy and enthusiasm of Devlin and his band are captured by the single microphone. Drummer Tony Hopkins rolls his snare like a machine gunner, and saxophonist Claude Papesch is a man possessed. Fronting them, with muscular delivery, is Devlin. One day, this historic recording will also see the light of day and help separate myth from reality in the Johnny Devlin legend.

--

The Blue Smoke programme featuring the Devlin audition and a sample of the 1958 live recording can be heard at RNZ’s website: