In 1962, Auckland schoolboy friends Dennis “Nooky” Stott, John Williams, Terry Rouse and Harry Leki formed a band called the Young Ones, changing their name to the Rebels the following year. As the original name suggests, their repertoire was mainly based on Shadows-style instrumentals.

After school the guys would meet at the fish and chip shop on Ponsonby Rd where Nooky’s mother worked, buying a shilling’s worth of chips and a potato fritter before retreating to the basement flat of John’s parents, in nearby Pompallier Terrace. “Mum and Dad used to rent the flat out and when the tenants moved out I commandeered it as our rehearsal space,” recalls John.

Backed by supportive parents, the band concentrated on private functions and school dances while building up their musical skills. It was also a coming-of-age period for the four teenage school mates.

“We were offered an evening gig in a coffee lounge at the top end of Queen St,” says Nooky. “We would finish at 10.30, so our parents would come and pick us up. Unbeknownst to us it was a topless strip club as well. At the last minute one of the parents found out. We had already committed to doing it so we went ahead, with parental supervision.

“Here’s John Williams, who was 13 at that stage, and this chick turns around to face us and winks, unbuckles her bra, turns to the audience and takes it off, then drapes her bra over John’s guitar neck. That was our introduction to the nightclub scene.”

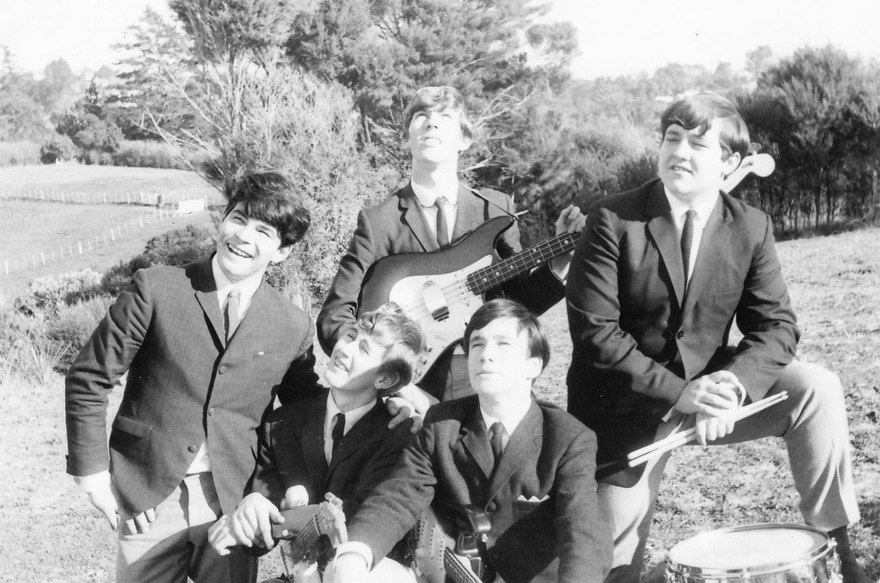

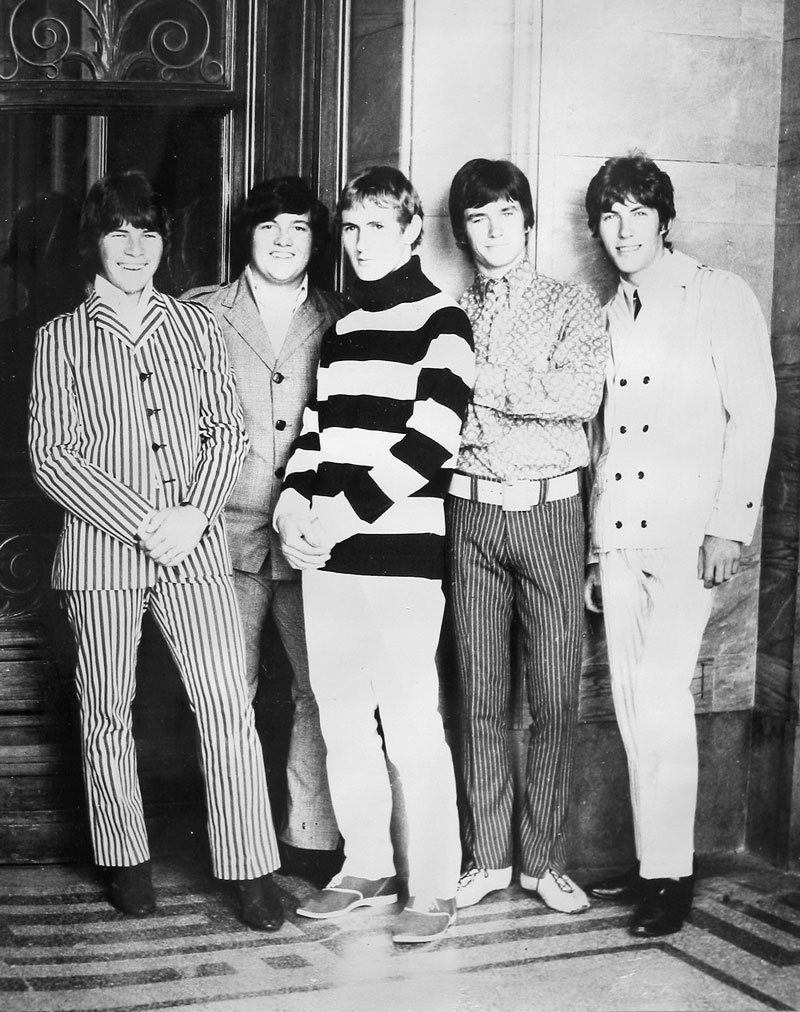

Larry's Rebels. - Grant Gillanders Collection

Cutting a fine swath in their red and black jerkins, black ties with Italian-styled trousers, their reputation as a well-groomed and proficient band which belied their ages soon brought them to the attention of New Zealand’s only dedicated pop magazine at the time, Teen Scene.

Columnist Toni McRae described them in a February 1964 article as “neat, dashing and having cheery boyish smiles and led by 13-year old John Williams, a cute bundle of dynamite on lead guitar”. The article went on to praise their sound. “At first when audiences are confronted by the band, they are a little bit dubious, but a couple of twangy, rip-sounding numbers and all doubts are dispelled as this group the Rebels lay claim to be Auckland’s only real band with a true claim to have a wild crazy beat of youth.”

Larry's Rebels 1965 - Barbara Fraser Collection

With Beatlemania in full flight, a change of direction was seen as the best way forward and a chance meeting with young aspiring singer Larry Morris soon changed the band’s direction.

It was a meeting decreed by fate and came at a great expense to the economy of the King Country area of Taumarunui.

Larry’s first job was at the Manunui sawmill, 20 minutes south of Taumarunui. “On my first day at work I was tasked with helping to unblock the frozen water pipes that carried water to the blades,” he recalls. “We were given lit, diesel-soaked muslin clothes on a stick to run along the pipes. My flame went out but it was still smouldering – so I yelled out, ‘Hey, what do I do with this, boss?’ Go into the shed and refuel it was his reply, so I went to the fuel shed and here are these three 45-gallon drums lying on their sides in cradles. One was marked ‘P’ for petrol, the other two were marked ‘D’ for diesel, I presumed so I put my smouldering cloth under one of the ‘D’ marked drums. Unbeknownst to me it was marked wrong and was actually petrol. WHOOSH, there was an explosion which threw me through the air, singeing my eyebrows and scorching my face and hair as I was being hurtled backwards.

After the timber mill fire, said Larry, “I could see that I was being set up as the scapegoat ...”

“The fire quickly spread through a shantytown-like pile of motley old wooden buildings. By the time the local volunteer fire brigade arrived, the mill had burnt to the ground. Obviously shaken, I could see that I was being set up as the scapegoat for their incompetence so I quickly got out of there. I noticed that the office was still standing so I popped in and enquired about my pay and was greeted with looks that could kill, so I took that as my cue and raced off in Mum’s Fiat Bambina that she had loaned to me.

“The local copper came around to see Mum and Dad that afternoon and suggested that they get me onto the next bus out of town as he couldn’t guarantee my safety – half of Taumarunui and the surrounding area’s population owed their living to the yard. I quickly packed a bag and Dad drove me to the NZR depot where I caught the bus to Auckland and stayed with Aunty Wyn. Mum and Dad settled up their business affairs and followed me to Auckland a short time later. A few years later when Larry’s Rebels played in Taumarunui an eagle-eyed local journalist asked if I was the same Larry Morris that burnt down the mill. ‘No no, not me,’ I replied, it’s a pretty common name. I left enough doubt in his mind for him not to reveal me in the local press. Phew – the last thing I needed.”

By 1964 Larry’s parents had moved up to Auckland and taken over a dairy/superette business in Herne Bay. “It was a fairly bohemian suburb at the time with several of Mum’s regular customers being musicians, artists and minor celebrities, including a compere comedian named Johnny Watson. My mother was always keen to see me working and told Johnny I had been singing and entertaining the family and friends since I was eight. As a result Johnny arranged an audition for me with Benny Levin, a local booking agent and manager. I was told I would need one song for the audition and that there would be a band backing all those trying out for the agency. The Cliff Richard hit ‘Living Doll’ was my choice and I was very happy to discover the band knew it well.

Larry's Rebels in 1965.

“As it happened Benny Levin said I was nothing special but the backing band thought I was great. When they found out that I lived in the area they offered me a ride home. I remember the drive home like it was yesterday. We were all in Dennis’s mother’s Austin 8. The lead guitar player Johnny asked me what I was doing the following Friday. When I said ‘nothing much’ he asked if I would come to the Saint Columba church in Grey Lynn at 7.30pm and sing a few songs with the band. I told him I would love to. What a night it turned out to be! We sang every song that we mutually knew. On the way home they asked me to join their band, the Rebels.”

By this stage the group’s original bass player Harry Leki had left, replaced by a succession of bassists. John Williams recounts an early audition for a new member. “This tall bloke called Trevor Wilson from Westmere turned up to audition. He was so nervous that he couldn’t figure out why he couldn’t get any sound from the amp, so I leaned over and turned it on for him. He didn’t get the job and the next time I heard of him was as the powerhouse bassist in The La De Da’s, a few years later.”

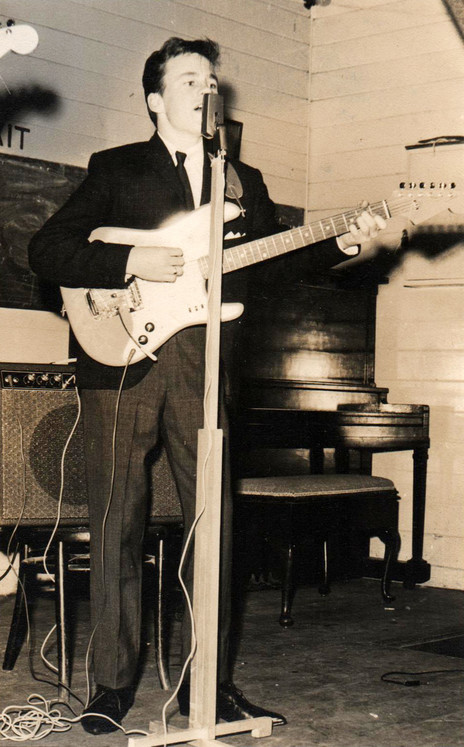

John Williams in 1964 with a wooden mic stand he made in woodwork class at school. - Grant Gillanders Collection

Harry Leki would resurface later as a member of The Simple Image in 1967. Cass Gascoigne of the Simple Image recalls, “Harry always used to tell us that he used to be in the Rebels, but none of us ever believed him. Pull the other one, we would say. Fifty-plus years later I find out he was telling the truth – well blow me down.”

Viv McCarthy, son of legendary rugby commentator Winston McCarthy, eventually completed the jigsaw. “A mate of mine told me about the Rebels needing a bass player,” recalls Viv, “I turned up at John’s parents’ place where the group was rehearsing. I bluffed my way into the audition by telling them that I had a mountain of gear in storage, but in reality I had nothing, and used their bass player’s gear as he hadn’t left yet. We played the ‘Rise And Fall Of Flingel Bunt’ and a couple of others and they said they’d let me know. A couple of days later they called and asked me to join.”

And so was born the definitive line-up of Larry’s Rebels: Larry Morris, John Williams, Terry Rouse, Dennis “Nooky” Stott and Viv McCarthy.

In March of 1965, the Rebels appeared on the bill for the Miss Auckland finals at Auckland Town Hall along with the country’s top band, Ray Columbus and the Invaders. Russell Clark, who was managing Ray and the Invaders, was impressed with the Rebels and invited them to his office the next day to discuss how he could make them successful. Afterwards, said Clark at the time, the band was impressed and after talks with the parents, they signed.

Clark hit the ground running with his new charges, changing the group’s name to Larry’s Rebels which was mutually agreed upon – then securing a long-term residency at the Top 20 club in central Auckland.

Larry's Rebels at the Top 20. - Kurt Shanks collection

The Top 20 residency lasted for most of 1965 and served as a perfect musical apprenticeship for their musical journey ahead. Having a residency meant even more rehearsal time was needed, to add more to their already impressive song list.

Also long was the set of rules imposed by the club’s management, including an array of fines for such misdemeanours as 10/- ($1) for arriving later than 10 minutes before commencement of that night’s performance, with another £1 ($2) fine for any member not ready at the start time.

Other rules included:

The club was out of bounds to the band members outside performing times.

A minimum of three new songs had to be added to their repertoire each week.

The band had to play the first set non-stop for an hour, followed by a three-song jukebox break.

Further sets should be no less than 30 minutes with a five-minute break.

The musicians were entitled to three glasses of orange juice per night. Anything else had to be paid for. (Actually, the group would often sneak rum or vodka into the club.)

Band members weren’t entitled to bring girlfriends or friends to any performance unless admission was paid for. Friends weren’t allowed at rehearsals.

All members had to remain on stage during the entire set and had to stay in the band room (the broom closet) at all times during breaks.

Although the rules were draconian, they weren’t too far removed from the school rules endured by John and Nooky, who were both in their final year at college during 1965.

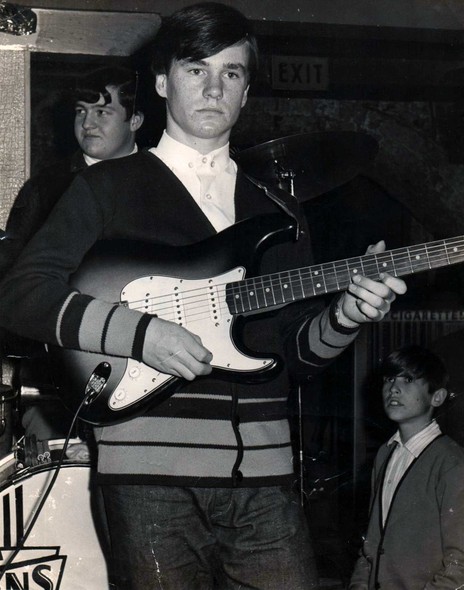

John Williams at Auckland's Top 20 club, circa 1967. Nooky Stott is behind him. - Larry Morris collection

In mid-year the group were signed to Philips Records (NZ) for a two-record deal. Work immediately began to find a suitable debut disc. The sessions were held at Stebbings where the group felt comfortable having recorded numerous demos there during the previous two years. The Burt Bacharach/ Hal David song ‘This Empty Place’ was recorded and then rejected. A Ray Columbus track, ‘Mad At Me’, was also recorded and given a catalogue number before it too was rejected.

It was back to the drawing board. The group re-recorded ‘This Empty Place’, this time to everyone’s satisfaction. Viv McCarthy: “The one thing I remember was John Hawkins the engineer suggesting that I double the bass lines on piano to give it a more rounded sound. Subsequently, I used this many times in later sessions especially in the slower, quieter tracks.

Larry's Rebels - This Empty Place (Philips, 1965)

‘This Empty Place’ was released in early September to excellent reviews and much publicity. The first pressing sold out within seven hours and eventually sold 4000 units.

Their second single ‘Long Ago, Far Away’ was released a short time later, coinciding with their first television performance on New Faces alongside a solo Ray Columbus and the up-and-coming Sandy Edmonds. Reviews and letters to the editor praised the group for their polished performance and neat appearance. One reviewer called the group “the best new discovery since plastic”.

Larry's Rebels - Long Ago, Far Away (Philips, 1965)

Ray Columbus also had lavish praise for the group, while popular group The Four Fours (later The Human Instinct) admired the group in a more covert way, as Fours’ member Bill Ward explains: “Their reputation around town was becoming well known, we would sometimes disguise ourselves and slip into the shadowy recesses of the Top 20 and watch the group – we were older than them and had been playing longer, but we learnt a few things from them.”

Nooky Stott gained an unexpected fan after the television appearance. “I had a really great headmaster at Auckland Grammar. He had been dismissive of my musical path and growing hair, but things changed after New Faces. He took great interest in me, and I never had any trouble with the length of my hair or anything else from that day on.”

Larry's Rebels drummer Dennis "Nooky" Stott. - Grant Gillanders Collection

In early 1966 their manager Russell Clark and promoter Benny Levin formed the independent record label Impact Records with a now-solo Ray Columbus and Larry’s Rebels among their first signings.

In February the group toured the country as part of the Tom Jones and Herman’s Hermits tour. The group weren’t overawed by their illustrious headliners, who all took a liking to the young Kiwi band. Nooky: “We were sitting in our dressing room after one of the early shows when there was a knock on the door and in walks Tom with a dozen bottles of beer – ‘Hi fellas, I’m Tom Jones.’ Tom used to watch the Rebels from the side of the stage and would regularly socialise with his new Kiwi mates.”

An extraordinary meeting of 60s pop talent. Taken in 1966 on the Tom Jones tour, promoted by Phil Warren. In front, Lew Pryme and Larry Morris; from the top, Tom Jones and Ray Columbus.

The group’s next single was their version of ‘My Prayer’, a song that Jones sang every night on tour to rapturous applause. The song went down well with females in the audience and the group, seeing its appeal, decided to record it.

The ballad ‘My Prayer’ may not have been what a lot of fans wanted to hear but their next single was: a commercial and powerful version of the Who song ‘It’s Not True’. Their previous singles had all been mid-tempo or ballads and this was a raw, ballsier Rebels.

“LARRY WAS SWINGING HIS WAY THROUGH A SONG WHEN SEVERAL GIRLS ADVANCED ON HIM AT GREAT SPEED ...”

Beginning on August 6, Larry’s Rebels, along with seven of their Impact stablemates, toured the North Island of New Zealand for a month, minus a US-bound Ray Columbus. Publicity-wise the tour got off to a spectacular start in Whangarei after a semi-concussed Larry Morris was pictured on the front page of the Northern Advocate clutching his head after retrieving himself from a melee of female fans who had grabbed him after he descended from the stage.

The paper reported, “Larry was swinging his way through a song in front of the first row when several girls who were making appropriate noises advanced on him at great speed and were soon followed by others.” Another reviewer noted, “Larry’s decision to leave the stage was done with his eyes open – even if, a minute later, one of them was painfully closed.”

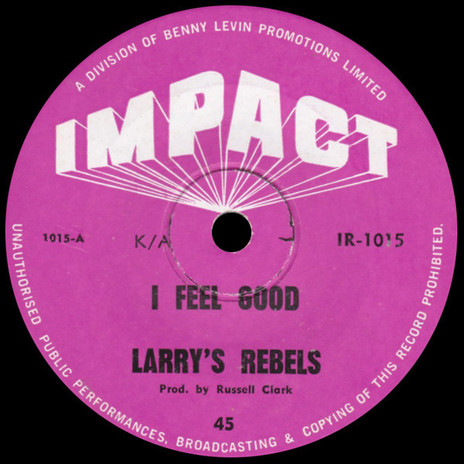

Their fifth single ‘I Feel Good’ – by New Orleans songwriter Allen Toussaint – was recorded after Nooky taped the song on his shortwave radio set. The version they heard would probably have been the Artwoods, whose live recording was broadcast on the BBC’s Top of the Pops programme on 8 August that year.

Larry's Rebels - I Feel Good (Impact, 1966)

The much-anticipated pilot for the local pop show C’mon hit New Zealand screens on 26 November 1966. It featured Mr Lee Grant, Sandy Edmonds, Herma Keil and The Keil Isles, Larry’s Rebels, Howard Morrison, and The Chicks. Larry’s Rebels performed their brand new single ‘I Feel Good’ and the Beatles’ Revolver album track ‘Got To Get You Into My Life’.

Several eagle-eyed viewers wrote to newspapers asking who the strange man was, seen frantically running across the screen behind Peter Sinclair after Larry’s Rebels’ final number.

Larry Morris: “During our last number the rest of the band were positioned around the set with me on the ramp. In my enthusiasm I decided to do a grand finale and in the spur of the moment I leapt up into the air as the song finished, which always looks good. I severely underestimated the steepness and width of the ramp and when I came down I fell off the edge and landed smack on top of the slide projectionist, whose job it was to project images onto the wall behind the stage. I was briefly stunned and my initial reaction was ‘shit!! I’ve killed the poor bastard’. A second later he snorted, shook his head and carried on projecting.”

“I decided to do a grand finale and leapt up into the air as the song finished” – Larry filming TV show ‘C’mon’.

Seeing his main star vanish off the side of the stage, Rebels manager Russell Clark then darted across the stage as the camera cut to the unflappable Peter Sinclair. Such was the hectic pace of the show, only a few viewers seemed to notice.

By late 1966 the New Zealand pop music scene was slowly coming of age. The film Don’t Let It Get You, featuring a plethora of local pop stars, had been released in October; the pilot episode of the Kevan Moore-produced television pop show C’mon, featuring Larry’s Rebels, screened in November and was greeted with unanimous praise from press and fans alike.

Larry’s Rebels were at the forefront of this new and exciting awareness of local music, along with a new wave of up and coming local acts who would all benefit from the other main happening about to begin: Radio Hauraki.

In December 1966, Radio Hauraki – New Zealand’s very own pirate radio station – began broadcasting from the Hauraki Gulf. Larry’s Rebels’ new single ‘I Feel Good’ had been released shortly before their first broadcast. The station, broadcasting to the top half of the North Island (sometimes further if atmospheric conditions were kind), adopted the song and the group.

With its nagging anthemic riff, hook-laden chorus and gymnastic backing vocals, ‘I Feel Good’ was tailor-made for radio. Although it didn’t make the national charts it is possibly New Zealand’s biggest turntable hit of all time. You couldn’t escape hearing it during our summer of 1966/67 when it stayed at No.1 on the Radio Hauraki charts for a number of weeks. In the 1970s Golden Harvest and Citizen Band both recorded versions of the song.

Larry’s Rebels finished the year in a publicity masterclass spearheaded by Russell Clark, who seized on an opportunity relating to John Lennon’s misquoted remarks about the Beatles being bigger than Jesus. Local minister Rev D G Sherson commented on local television that the Beatles would be welcome at his Birkenhead church anytime. Clark rang Reverend Sherson and told him, “The Beatles may not be available, but Larry’s Rebels would be only too keen to come along.”

The group performed at Birkenhead’s Methodist Church during the Sunday evening service on 11 December. They performed ‘I Believe’, ‘The Very Last Day’ and the hymns ‘Praise The Lord’ and ‘The Lord Is My Shepherd’ while Larry gave a brief sermon on the problems faced by male teenagers. The usual congregation of 40 members swelled to nearly 400 and the church’s supper room was brimming with the overflow of instant teenage conversions. The service gained much exposure and publicity for the group.

Starting in Christchurch on 30 January and spread over four centres in four days, the Rebels supported the Yardbirds, the Walker Brothers and Roy Orbison. The Yardbirds and the Rebels took an instant shine to each other with the two guitarists, Jimmy Page and John Williams, bonding immediately.

Williams recalls: “Jimmy would grab me and the two of us would sit at the back of the tour bus and jam. He gave me the riff and chords to ‘Train Kept A Rollin’, which became the platform for the ‘Flying Scotsman’ track that we recorded for our A Study In Black album a few months later.”

On the afternoon of the third concert in Hamilton, some of the Yardbirds took advantage of a precious few hours off, and headed to a nearby hotel, safe in the knowledge that they would be relatively anonymous there. “Jimmy was still pretty hammered by the time they were due on stage,” remembers John.

What happened next is an experience that most people with even just a morsel of musical ability would be highly envious of.

John Williams: “The Yardbirds came back from a session at a pub that day along with a few others from the tour. Jimmy was well under the weather, so much that he could hardly stand up.

“We had played our set and as usual I would stand at the side of the stage to watch the other acts every night. With the Yardbirds just about to hit the stage, Jimmy was still staggering and could not play so their singer Keith Relf took his white Telecaster guitar, handed it to me and said, ‘You’re on’. ‘No worries,’ I replied. I played three songs from the side of the stage without venturing out fully so as not to muck them up with the crowd. By the end of the third song Jimmy had composed himself enough to re-join the group. It was a breeze as I had grown up with those songs.”

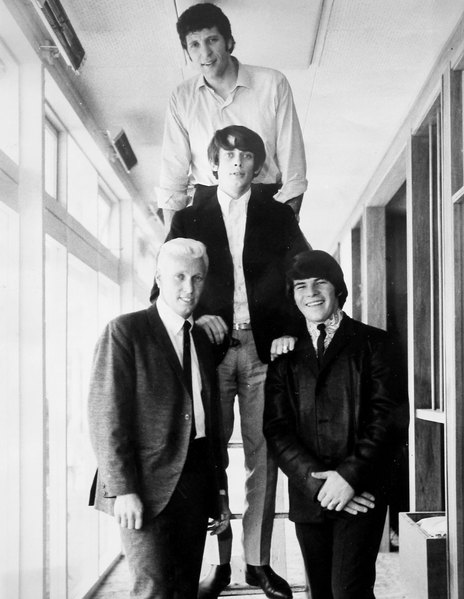

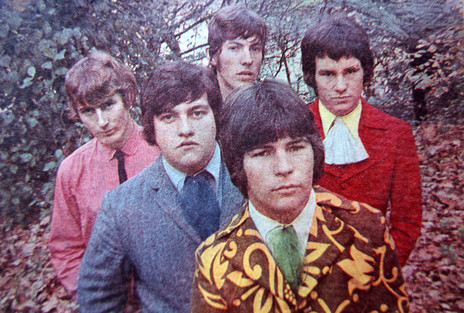

Larry's Rebels outside Auckland Museum in 1967: Larry Morris, Nooky Stott, Terry Rouse, John Williams and Viv McCarthy

In a mock ceremony at the after-tour party Jimmy gave John his guitar strap, Tone Bender fuzz pedal and the silver shirt that he wore on stage. The response from the audience for Larry’s Rebels during the tour led Keith Relf to comment, “If the Yardbirds weren’t such a major force internationally, then they would have found it hard competing with Larry’s Rebels.”

No sooner had the dust settled on that tour than posters started going up for an upcoming tour to start in April: Eric Burdon and the Animals, Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich, and Paul and Barry Ryan, with Larry’s Rebels in support.

The group started recording tracks for their debut album in early April. It was arranged for the group to record after hours at the AKTV2 television studio in Shortland St. Garth Benfell, the sound engineer for C’mon, engineered the sessions.

After finishing each evening’s gigs, the group would arrive at AKTV2 studio, unload their gear in the foyer and wait until the last live broadcast of the night. As soon as the red light went off after the final transmission a team of staff members would quickly move the group’s gear into the studio like a swarm of ants, before finishing for the night and leaving them to it.

Larry and John wrote five tracks for the album. They also recorded songs from some of the artists that they had toured with, including Tom Jones’s version of ‘Skye Boat Song’, the Walker Brothers album track ‘Saturday’s Child’ and the Animals track, ‘Inside Looking Out’ (at the same session they recorded the Animals’ ‘You’re On My Mind’ as the B-side of their ‘Painter Man’ single).

The tour with the overseas stars was hectic, both on and off the stage.

The Rebels backed Paul and Barry Ryan and came in for special mention from the brothers and the press for handling their complex arrangements with aplomb. Nooky: “Paul and Barry Ryan had orchestrated arrangements. We told them that we could all read music so we asked them to send out charts and singles to study before the tour. None of us could read music really, but we sat down and studied what they had sent us and we worked out where the stops and beginnings were, so that we could bluff our way through it. I had my music stand there with the music on it, which was quite decorative, but I never looked at it once. But they didn’t know that.”

Paul and Barry also tried to get the Rebels added to the Australian leg of the tour and eventually into the UK. They made several calls to their mother, Marion Ryan, who had been a big UK star during the fifties and was very well connected. Viv McCarthy: “We were in their room one night as they rang their mother to arrange for her to ring her friend Sir Lew Grade about the possibility of getting the Rebels into the UK. It soon became apparent that the unions would be a big problem and nothing eventuated.”

Larry's Rebels. - Grant Gillanders Collection

Paul and Barry were also impressed by Larry’s Rebels’ stage gear. With a screen test with MGM Studios in LA planned for after the tour – and wanting to look as sharp as the Rebels – the brothers bought replicas of the Rebels’ Hawaiian print jackets from His Lordships in Auckland’s Vulcan Lane.

Meanwhile, John had an altercation with Animals guitarist John Weider. “The tour bus rolled up to the Geyserland Motor Hotel in Rotorua. There were hundreds of fans milling around the bus and no security. The Animals’ guitarist John Weider also played a white 65 Fender Telecaster, the same as me and his guitar had been stolen during the melee of arriving at the hotel. He came up to me and claimed that I had his guitar. ‘I don’t think so, see it has my initial JW on the neck,’ I replied. ‘Yeah so have I,’ he said. I eventually caught him out with a distinctive black mark which he wasn’t able to describe. He knew all along that it wasn’t his, I was very disappointed that he tried to get one over on me but I still let him use my guitar for the rest of the tour.”

After the show in Rotorua, scores of teenage girls laid siege around the touring party’s hotel where the manager, his wife and the night porter spent the entire night patrolling the grounds with dogs to keep the girls out. “FRANTIC GIRLS RUN WILD” ran the Rotorua press headline on the next edition, which also featured a great quote from Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich’s manager. When asked why two members of the group swam naked in the pool, he replied, “Because they had consumed half of the contents of the bar.”

--