AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Simon Kong

It was an era when dance music was infiltrating the international pop mainstream. Closer to home, a warehouse rave scene was emerging around New Zealand. Long obsessed with hi-fi gear, radio and records, Simon was fast becoming the music guy at parties. He even hosted a rudimentary dance party at a community hall. “I was really innocent. I thought everyone would dance. Everyone turned up drunk and ended up throwing up in the bushes.”

Around the same time, he started noticing rave flyers and posters around town. The promotion for a rave called Ultrasonic really jumped out. “I thought, ‘who are these guys, they can't be doing this. I discovered this!’ I turned up and what they were doing totally blew my mind.” After arriving at an old theatre, he was greeted by lights, visuals, DJs and happy lollypop-sucking ravers. “I felt like I'd found a door into another universe. I knew all the separate components they were using, but I'd never seen them all put together at once. It just felt so free.”

Taking that night as inspiration, Simon embarked on a 20-year-plus journey, spending time living in Dunedin, Nelson, Wellington, Sydney and Queenstown along the way. Since then, he's been involved in progressive dance music culture on a variety of levels.

Starting out as a DJ, Simon found a natural affinity for the technical side of event production.

Starting out as a DJ, Simon found a natural affinity for the technical side of event production. It led to him working on seminal outdoor festivals like The Gathering, Canaan Downs Festival, Rhythm & Alps, and Homegrown. Alongside these endeavours, Simon has thrown raves and club nights nationwide, worked with experimental music organisations, dipped his toes in electronic music production, and helped to pioneer podcasting in New Zealand.

Based back in Christchurch since 2007, Simon runs The Greenhorn Production Company and its subdivision Kidnap Inc. These companies provide sound system hire, event production services, and handle music bookings, design and promotions for nightclubs and brand events around the city. He continues to DJ and play live electronic music sets under a variety of aliases.

Childhood and early teens

Simon was born in Thailand in 1972, of Fijian-Chinese and Scottish-Irish-New Zealand descent. He spent his childhood in Thailand and Malaysia, while his Christian parents took part in missionary work. “I went to a British boarding school in Malaysia, then an American boarding school in the Philippines in my early teens, where I studied an English O level curriculum,” he recalls. “It was this weird Commonwealth mash-up. All the Kiwis, Canadians, English and Australians were lumped separate to the Americans, but we'd still go to pep rallies.” He sang in choirs and learned piano and flute.

While his older brother was a hair metaller, Simon gravitated towards dance music. Ironically dancing was banned at the boarding school. “We'd have school balls and instead of having a dance, we have a slide show,” he laughs. “Four inches was the closest you were allowed to a member of the opposite sex. It was very Footloose.”

Through religiously listening to the radio and watching music television, he also found himself connecting with songs by Johnny Hates Jazz, Salt ‘N’ Pepa, Pink Floyd and The Chills. Having been raised on church music, gospel and Christian rock, the experience was a secular awakening.

In 1990, Simon's family moved home to New Zealand. “When I got back I was a cultural sponge. I had a really weird British American accent, and I looked ethnically ambiguous. I had no pop culture reference, but I was very global. We didn't even have a TV at home. I was very out of sync, but I knew I liked music.”

Spending his Saturdays at local record stores, Simon would use the Top 40 charts as a guide. “If I liked someone's single, I'd check out their albums.”

He was also really into contacts and networking. “I would keep a book with me and write everyone's numbers down in it. If I saw people doing something cool, I'd go and ask them who they were, and get their details. I'd ring everyone on the weekend and see what they were up to. I'm surprised people put up with me. I was an ultra-nerd. Because I was out of sync, I didn't have any concept of social cliques.”

Soon enough, he was sneaking out at night and into clubs.

Introduction to hip-hop and rave culture

When he was 18, Simon went flatting in an inner city apartment. Learning the basics of DJing on a friend’s belt drive turntable and two channel mixer, he started playing hip-hop records.

As he became more interested in DJing and rave culture, Simon began collecting audio gear and buying and selling turntables. “I sold [DJ] King Al his first turntable for $40 cash over the counter of the café he was working at.”

As this suggests, his entry into DJ culture was an experience equal parts rave and hip-hop. “Me and my friends were trying to be homies on the street,” he laughs. “We'd play hacky sack in super baggy jeans. In my vernacular, I was hip-hop, because that was what my friends were doing. But if there was a rave on, I was there.”

Seeing how obsessed Simon was becoming with DJing, his older brother bought him his first Technics 1200 turntable.

After some prompting, he became the scratch DJ in Christchurch's first live hip-hop band Nil State (fronted by a young Maitreya). Seeing how obsessed Simon was becoming with DJing, his older brother bought him his first Technics 1200 turntable. “It took me about fifteen years to pay him back. I used to cart it and my little mixer around to gigs on my bicycle.”

Simon started coming across flyers for raves in other parts of the country. He moved to Nelson to pick apples, but ditched that and moved into the town centre, where it was all happening. There he DJ'd at a youth nightclub, attended Goa and Psy Trance parties, and befriended respected DJ and music critic Grant Smithies. “I would have been around twenty,” he recalls. “I can't express how blessed I was to meet Grant. I was manic, living a terrible lifestyle. He mentored me and gave me time.”

For the next few years, Simon spent summers in Nelson, fringing around the Entrain Crew or the “Myan Space Moon Tribe”, and winters in Dunedin. In Dunedin, he worked as the sound guy for rave/philosophy collective Eudeamony. At their parties, Simon was introduced to the deeper dub techno sounds coming out of Germany and the UK. “It was a different environment. It was pagan and ritualistic. If you want to go deep in New Zealand rave culture, it all goes back to Eudeamony. They took the ethos of rave and put it into philosophies that referenced proper scholarly texts to contextualise what we were doing.”

As part of their events, he helped organise ambient rooms/zones. This was his introduction to the Dunedin experimental music scene. “We lived in a place called The Opera House. It was a mixture of McGillicuddy Serious Party people, ravers, and vegan anarcho-punks. The alt-societies were all linked there.” During summer in Nelson, he bluffed his way into crewing on seminal New Year's Eve raves Entrain and The Gathering. “I can never tell with hindsight whether people just tolerated me or actually thought I was in charge of stuff,” he admits with a chuckle.

The Gathering years

At the second Entrain festival, Simon befriended Murray Kingi and Grant Ellis. At the end of the party, he helped load the PA out. At the third Entrain, Simon barged his way onto the technical crew. “I was part of the mythical car ride afterwards where Murray was like, ‘Stuff this, let's just do a festival ourselves,’” he recalls. The Entrain boys were lost in their cosmic space-time world, and while I respect that, we'd done all the physical work to produce the party.”

When Murray began meeting up with Grant Smithies, Greg Shaw from Everyman Records and Jose Cachemaille to plan a new New Year's Eve festival called The Gathering, Simon continued his modus operandi of barging in. “They used to meet at a vegetarian café in Nelson called Zippies. I'd turn up and bug them. I told Grant I had to be involved.” They gave him an official job, and he worked for five days straight at the first edition of the event. “I did the lighting for two zones and everything else I could. I guess that is how I got myself into the centre of everything. You couldn't get rid of me.”

It was 1996, and as a festival, The Gathering's original mission statement was to run until the year 2000. Every decision Simon made for the next few years hinged around seeing himself as a core part of the event. He spent the year as the Christchurch regional coordinator. After being blown away by Wellington DJ collective The Jewel School, Simon moved to the capital in 1997. He briefly attended university, threw warehouse rave parties with friends, worked in sound and lighting, and became the Wellington regional coordinator for The Gathering.

In 1999, Simon moved to Sydney for a year with his girlfriend of the time. He worked for a Greek disco hire company named Black Express and explored the city's club scene. At the end of the year, Simon returned to New Zealand for the seminal year 2000 edition of The Gathering.

“We had a big meeting after the 2000 Gathering. Financially it wasn't working.” Murray wanted to push ahead with another event. Simon suggested taking a year off and was outvoted in the meeting. “I didn't want to leave them in the lurch, so I said, I love you guys, I'm in if you want to do it.”

The 2001 edition came around, and his responsibilities stepped up. Simon made himself the head of the tech crew and wrote his own salary.

“That was the year that made me and broke me,” he admits. At the end of the event, it became apparent that they’d lost a lot of money. Murray asked him to sit outside the office and tell people looking to get paid to go away and come back later. Simon sat outside the office for three days. On the third, he was done. He hopped in a car with his girlfriend, and they drove as far south as they could. “I was so deeply embarrassed. It was my deals and word that had got some of these people there, and we couldn't pay them. I just wanted to go somewhere no one knew who I was.” His sister was living in Queenstown, so they headed there.

Queenstown, Christchurch and the Greenhorn Production Company

In Queenstown, Simon started DJing at local bars and throwing club nights around town with his girlfriend of the time. The sounds of UK garage/2-Step had just arrived in New Zealand. Captivated by the music, he followed that thread, playing deep house on the side. He also did sound and lighting work. “I did what I'd always done. I got to know everyone and inserted myself into the scene.”

When podcasting arrived as an online broadcast format, Simon was an early adopter. He became involved in a world of wireless bedroom broadcasting, Internet record labels and modern minimal techno. “We even got on the TV news for podcasting,” he recalls.

In 2007, Simon met and married his wife. They decided to move back to Christchurch and start a family. After working freelance with a lighting company called Illuminati, he started up The Greenhorn Production Company. They began providing PA hire, technical production, event management, design, entertainment and beyond to a mixture of clients inside and outside of the entertainment sector.

Around the same time, he got talking to his friend Ben, who had spent some time in Ibiza. “That was when I clicked onto the idea of parties as a brand as opposed to a feeling.” Ben explained events like Headcandy and Ministry of Sound to him. Previously, around 1999, the Fevah brand had arrived in Wellington and put 1,000 people into the Phoenix Nightclub. A change was in the air.

Ben convinced Simon they should do something similar, leading to the launch of their Kill Club brand. “When I was podcasting, I changed my DJ name to Turnstyle,” Simon explains. “In 2004 DJing went from playing music to people, to people coming up and asking for requests. They got really angry if you didn’t play them. That was when they started handing you their iPods. That was also the beginning of MP3 or controller DJs.” Simon’s rationale for Kill Club went like this: Clubbing is dead. You’re treating me like a jukebox, and in the process, you’ve killed the club. “It sort of went over people’s heads, sort of got me in a lot of trouble,” he chuckles.

Kill Club ran over two waves. They threw a series at the Civic, and a second series at the Meadi Club. Kill Club also did the odd renegade or pop-up show. “We turned up at this jungle warehouse party, set up a PA outside and rocked out a techno set. More people were outside than inside before we left.”

That year The Canaan Downs NYE Festival began. Simon was shoulder-tapped to be part of the committee. He organised one of the zones as well, making use of .3rd Space, a format he had been unofficially running at events around the country since 2004. “No one was booking me to DJ at parties anymore, so I started doing experimental spaces at parties.” Simon would arrive with his own sound system and lighting, and insert his own layer into the event. “I was of this ‘ask no permission’ vibe and I wanted to freak people out.”

Simon felt like raves had fallen into a pattern, and wanted to remind people they began as experimental environments.

Simon felt like raves had fallen into a pattern, and wanted to remind people they began as experimental environments. With The Canaan Downs NYE Festival, he evolved it into the .3rd Resistance, where he’d book a mixture of his older friends from The Gathering era and younger talent, mix them together, and have the DJs play hidden inside a tent. Having moved around so much, and been involved in so many different scenes, he wanted to pull people out of their isolated silos and make them mix. Sometimes it worked. Sometimes it didn’t.

After The Canaan Downs Festival died off, Simon was contacted by Bench Music. They brought him onboard to work in production on a series of events around the South Island. This eventually led into working on two editions of the Rhythm Group’s Rhythm & Alps summer festival. In parallel he began working as a stage manager at Jim Bean’s Homegrown Festival in Wellington, and became involved with Fabel Music’s USCA events.

The Canterbury Earthquakes, Kidnap INC

Things were trucking along until 2011, when the Canterbury Earthquakes hit Christchurch. “The status quo in Christchurch disappeared,” Simon remembers. Having long operated in a state of flux on the edge, he came into his own. He’d spent his entire career operating in the unknown; it was his element.

“I’m comfortable inside chaos,” he admits. He stopped pulling his punches, deferring and waiting for other people. “I took everything I knew and applied it in real time.”

Since then, it’s been a process of improvisation and re-innovation on a yearly basis. “Every year for the last few years, I’ve done slightly different things. It’s been a 180-degree turn every time. The clients change, the venues change, but it’s all similar in context.”

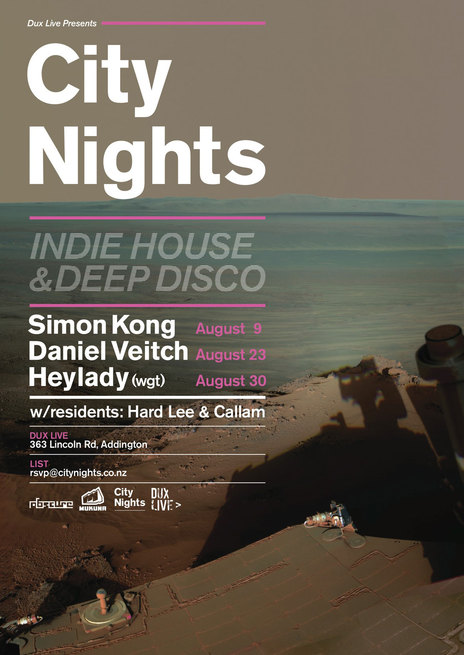

As the Christchurch rebuild progressed, Simon saw a lot of potential for a strong cultural future for the city. To support this, he established Kidnap INC as an event management brand underneath Greenhorn. Through Kidnap he's been booking entertainment for venues around town, running his own clubbing brands (City Nights and City Underground), and handling more commercial events.

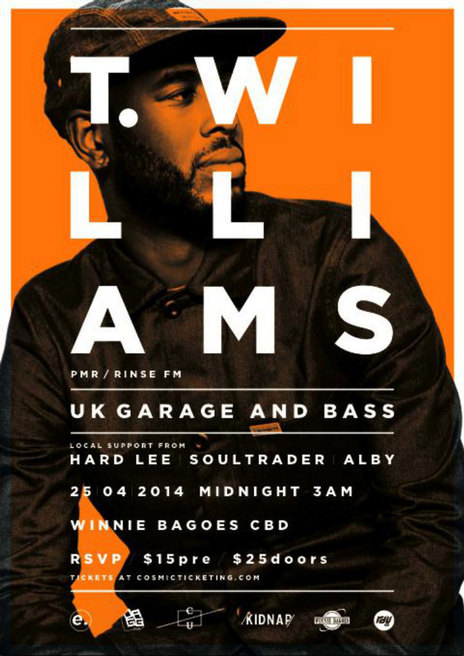

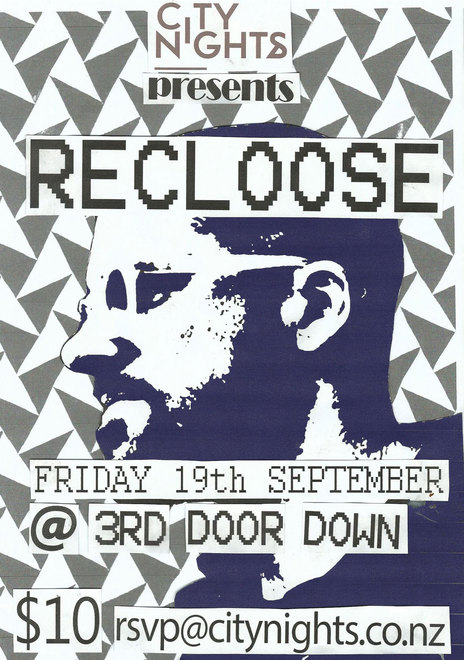

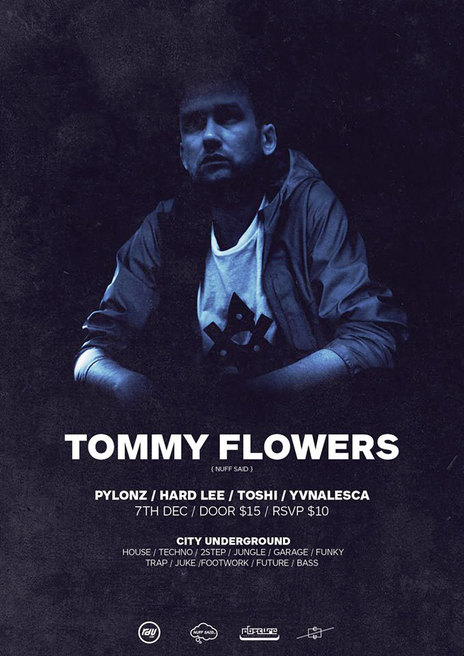

From an integrated standpoint, it's all been done with a window towards helping rebuild a viable local club music ecosystem. He's brought Andy Hart, Fantastic Man, New York Transit Authority, DJ Q, Peacekeepers, L.A.B., Tommy Flowers, Isaac Aesili, RIA, New World Sound, Komes, NOMAD, A Skillz, Dan Aux, Kid Sublime, Rondenion, Sampology, Tim Richards, GASP, Chores, Aroha, Recloose, Frank Booker, Max Graef, T.Williams and Wookie through the city. Simon also played a live multi-channel set alongside Laurel Halo for AltMusic, and DJs in clubs and bars on a regular basis.

“2014 was about a real effort on my part to present the music I love, in the way I love. The perceived way of doing things is about popularity and hype. People sometimes forget that electronic music and DJ culture are art forms, and emotional art forms at that. This is more than just a party. It's about movements, sounds and histories. I had a chance to represent all of that in the city I love, the city that introduced me to so much music. It was me trying to recreate that feeling Christchurch gave me in the past. I think in a business sense, I was also tired of doing other things. I wanted to do something I was passionate about.”

Simon plans to cut back on DJing and focus on his more experimental musical interests. “I'll get back to my multi-channel sonic arts and production. I'd like to present stuff that is in contrast to what I did this year. I need to keep myself feeling active and motivated. If I do one thing for too long, I get bored. I'd like to refine what I'm doing now.”

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air