Originally published as “Heaven is Just a Sin Away: the Warratahs’ Lament” in Rip It Up, February 1988

The action opens on Gore’s main street. Up drives a car: four cylinders, it must be some outsiders down for the country music awards. The car comes to a halt – maybe beside the pie cart, the one that threatened to sue when a national magazine described it as “sauce splattered” – and out pile five men. The Warratahs have hit town; town doesn’t flinch

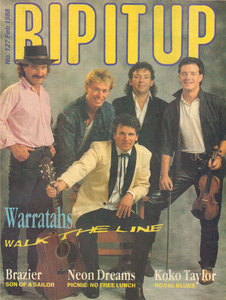

The Warratahs on the cover of Rip It Up, February 1988.

Wayne Mason, Warratahs’ pianist, chortles with delight describing their arrival in Gore. “It was like the classic movie of a gunfighter coming down the street, with everyone peering through their curtains. Five of us drove into town in this van packed with gear. That looked odd for a kick-off – it looked well organised! And we were all dressed in black, with our suits on, and the ties and Nik’s big leather belt ... it was like we’d come to deal death to Gore! “We went to the radio station for an interview. And the woman who was organising it came up and said, [whispers] ‘Don’t think you’ve got it easy – we’ve got some great opposition for you!’ ”

Barry Saunders, vocalist: “They see the awards like a big School Certificate, a big competition. That’s a very traditional approach. The joy of music would be … three or four down the list.” That was the Warratahs’ first brush with “the other side" – the New Zealand country music circuit. But they won the hearts of Gore, taking away several awards for their mellow, authentic honky tonk sound. Says Saunders, “They thought, ‘Woo, these boys are serious but obviously they’re not country, because we don’t know them and they don’t come from down here.’ ”

The Warratahs have got it sorted. A regular gig playing what they want to play, occasional tours and a new album that because of realistic production values (ie: small PA, few lights and live recording) aren’t financial burdens. Plus – believe it or not – airplay. But here you’ve got seasoned musicians who have finally found their niche. They’ve learnt to avoid the errors caused by ego and ignorance.

Dead flowers standing in a bottle ...

Barry Saunders and Wayne’ Mason were both in Rockinghorse and The Tigers in the 1970s; before that Mason was a key member of The Fourmyula. Now there’s a story that should be in Spinal Tap 2. To cut it short, the Fourmyula won the Battle of the Bands in 1968. The prize was a trip to England, “for which we were so grateful,” says Mason. “In 1968, that was like a life’s dream.”

There was a catch, however. “They needed a band for the boat, so they’d offered this prize. We then played about 10 hours a day for about four weeks! Hell no, not for pay! For nothing! They were going to have a band anyway, so offering it as a prize was a masterful coup. I never realised how incredible it was till years later, how we’d been led up a gum tree. I suddenly thought, that wasn’t a prize ...”

It got worse. While on board, the legend goes, Mason’s fabulous song ‘Nature’ topped the charts here. In England, the musical fashion was for heavy guitar bands in the wake of Led Zeppelin: Free, Spooky Tooth, Taste. So the Fourmyula bought new clothes, new amps, new haircuts. Running out of money, they sailed home. At the comeback gig, the crowd sat, waiting for the sweet harmonies of ‘Nature’. The curtain rose …

“It was terrible,” says Mason. “People were horrified. We’d changed personality: hair, clothes, music. The promoter rushed up and said, ‘Look, can I give you a little piece of advice. Change your repertoire. You’ll never work in this country doing that, mate!’ So don’t worry. The Warratahs are unlikely to carry out their threats of dry ice, silver suits, a blonde BV lineup and “keyboardists who spin round on their seats.”

Mason says that when he saw Spinal Tap it was so real, he was delirious with laughter. Performing at the Cricketers each weekend provides a chilling reminder, however. “It’s great playing downstairs,” he says. “But every band upstairs, the angst they go through. Downstairs everyone’s grooving along, but the people really trying to make it are upstairs. Going through the whole Spinal Tap trip, the big PAs and five people in the audience ... I know where I’d want to be.”

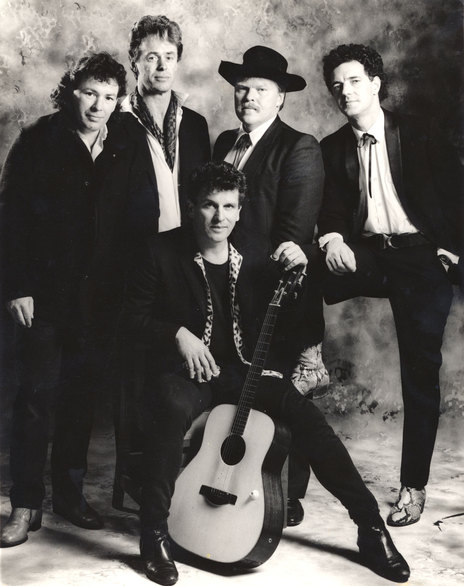

The short-lived Warratahs line-up at the time of this interview, February 1988. From left: Rob Clarkson, Wayne Mason, Barry Saunders (seated), John Donoghue, Nik Brown. - Photo by David Hamilton

Above all, what the Warratahs have is feel. Barry Saunders’ warm, true, and oh-so sincere voice, Mason’s lyrical honky tonk piano, the emotional bite of Nik Brown’s fiddle, and the understated backbeat of bassist John Donoghue and drummer Rob Clarkson. Together it’s a unit to make your feet dance and heart sing; depth of feeling and assured playing with no hint of a “hot licks” mentality.

“This band seems to have created a need in people’s lives,” says Mason. “Each time we play, we’re basically the same, we’re consistent. People have integrated the feeling we create as part of them. We’re not exceptional in that we don’t change their lives, but if we’ve been away they seem to find it reassuring to have us back, because they’ve missed the feeling we generated. It’s quite an unusual feeling.”

Faded picture of a secret rendezvous ...

For Nik Brown, being in a band of friends is the key. “We listen to each other on stage, and enjoy each other’s playing. I’ve been in bands where people don’t talk to each other for months, and I don’t want a bar of it again. Also, this band is entirely committed – they enjoy it, and have a respect for the music."

Brown says it’s no surprise country music is undergoing a resurgence. "Sincerity is the key – no bullshit. If you’ve lived at all, country music talks to you. We’ve had heavy raw punk, metal, electronic pop … what the public miss is something to whistle in the shower. People miss a good tune and good lyrics.”

Saunders: “I sometimes wonder what people look for in music these days, when I look at what’s selling and being played. People don’t seem to find any warmth in music anymore. It seems more like a conversation stopper.

“You can turn people off with volume. Now people feel freer to like what they really like. In the past here, people were very aware of what sort of clique they’re in. Now it’s okay to like a low-volume band or one that’s old! No one gives a fuck anymore!”

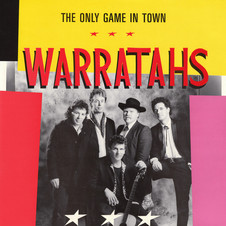

The original Warratahs line-up, which recorded the early singles and the debut album The Only Game in Town in late 1987. From left: John Donoghue, Wayne Mason, Barry Saunders (seated), Marty Jorgenson, Nik Brown. - Trevor Reekie Collection

Along with stalwarts like Al Hunter, the Warratahs are bringing country to a new audience. “It would be very easy to play the country circuit, which I love,” says Saunders, “but it’s more fun to take it to people who’ve never heard country before. That’s what was good about doing the Billy Joel support. When we first walked out on stage at Mt Smart I though, we’ve made a terrible mistake here! My heart sunk. They all rushed forward thinking we were Johnny Farnham, because we weren’t advertised on the bill. But we started, and the audience looked round at people they didn’t know, and they loved it.”

Mason: “The band seems to have a warmth that … seems to save the most desperate situation.” Like Taihape – 10 people on a Wednesday night. Or Karamea, where the local hall had a sign reading “No smoking, no drinking in this hall” – so the audience exited between songs for a smoke in the bike sheds.

“It’s funny these country towns,” says Saunders. “You always have this romantic notion of how it’s gonna be: a country town. It’s not like that. They want AC/DC. They hate country music! Country is alive in the cities, and a few other places, but where you’d think it’d be strong, it’s the opposite.”

Mason: “You’d think in Greymouth there’d be a John Hore cardboard cutout in every shop window advertising things. They thought we were pretty courageous, playing the Golden Eagle, a rock club, on a Thursday night.”

Saunders: “They put up a little resistance, they didn’t come quietly.”

I don't wanna look for your number ...

Of course, every so often all bands encounter scenes from Spinal Tap despite their experience. In January the Warratahs provided musical accompaniment for the Kapi-Mana country awards in Paraparaumu. Families devoted to country music from the southern North Island attended and drank raspberry while the Warratahs kept playing for 13 hours as 100 singers went through their paces.

“There were seconds between each new song,” says Mason. “One person ran on with the charts, one ran off. Barry had seconds to work out the feel, then we played it. That went on for 13 hours one day, on the trot. A break for lunch, and 10 minutes for morning tea. But you’d get kids of about three-foot high singing harmonies. Really young kids, singing in perfect thirds.”

“A lot of religious songs,” says Saunders, “which is great but not our sort of thing. “The instance of people singing the same song was quite great. They love it. Sing ‘The Banks of the Ole Ohio’ and they love it. Do one of your own, and they appreciate it, but if they’ve heard your record two or three times, they love it. When we did ‘Hands of My Heart,’ they really exploded.”

How about that. The Warratahs’ first single actually received airplay. From the student stations, naturally, but also Radio Windy and ZM in Wellington, plus a little in Christchurch.

The Only Game in Town (Pagan, 1987)

Recorded live at Wellington’s Broadcasting House studio, the Warratahs’ album The Only Game in Town mixes their own songs with four standards, though it’s hard to tell the difference. Saunders’ ‘Maureen’ could be by Roy Orbison, Mason’s ‘The Only Game in Town’ George Jones.

“That’s the theory we have about writing,” says Mason. “We’ve got our songs up against, basically, Hank Williams. I don’t think anyone’s surpassed him, ever. I really believe it. Well I’ve got to try and write them as good.” Saunders: “It’s very easy to write a cliched country song. A lot of modern country albums, the songs sound as if they’ve been written by advertising people. It’s very important that they sound sincere.”

The Warratahs avoid the gimmicky country songs, the ‘I Ain’t Married (But the Wife Is)’ numbers that don’t get past the first line. “We try and keep away from drinking songs and things like that,” says Saunders. “I always think they’re a cop out.”

Hank Williams’ songs had a universality that meant they reached further than the traditional country audience – and had a depth beyond cowboy cliche. “We couldn’t really sing about dusty trails, could we,” says Mason. “That’s what Hank’s great breakthrough was. The Gene Autrys bypassed real emotions rather than writing about stuff that’s truly miserable.”

Scratch a song by the Beatles or the Rolling Stones – or the Pogues – and you’ll find a country song. Barry Saunders played in a country band on the Irish circuit in England for three years. “They always used to witter on about how the Irish gave country music to America. Which is true.”

The net has spread so far that singing country is almost as natural in the South Pacific as Nashville. “I still find it hard to come to terms with American references though,” says Saunders. “In fact I stay away from songs with those kind of lyrics. We do ‘The Promised Land’ because it’s always been a real favourite, but I still find it hard to sing, ‘I left my home in Norfolk, Virginia, California on my mind ...’ Because I’ve never been to Norfolk, Virginia, let alone lived there.”

It doesn’t matter when you can write your own songs that transcend mere geography. The Fourmyula’s ‘Nature’ fitted the Zeitgeist of the late 60s as perfectly as Toy Love’s ‘Rebel’/’Squeeze’ did the late 70s, or The Swingers’ ‘Counting the Beat’ the early 80s. With ‘The Only Game in Town’, ‘Hands of My Heart’ and ‘Maureen’, Mason and Saunders have outdone many of the American songwriting greats who, like Hemingway’s writing block, can’t get up a good tune anymore.

Down on lost heart’s avenue

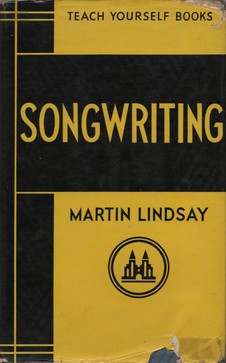

Wayne Mason began composing for the Fourmyula after reading one of those old black and yellow self-improvement books, Teach Yourself Songwriting, and he’d love to find a copy today, it was full of such good advice. Things such as stressing the importance of the first line: “It’s everything,” he says. “You have to involve people, like on ‘Maureen’ – Could be the time to change my address / And maybe find some peace at last – and once you’re involved, you’re away. People have got to know more. But you don’t give them too much too soon. Like gossip, you leave a cliffhanger to the end.”

Teach Yourself Books: Songwriting by Martin Lindsay (1955).

While ‘Hands of My Heart’ (Been a long time, I been waiting to discover / if I get the leftovers from your other lover) or ‘The Only Game in Town’ (When we were fighting / when we were ma-a-d) sound like preludes to juicy soaps, the bitterness and irony dripping from ‘Maureen’ is expressed with the naked simplicity of a classic such as ‘She Thinks I Still Care’: I had an eye on a new horizon / She had better things to do … Better things for Maureen.

Barry Saunders grew up listening to his parents singing along at parties, and has often paid his rent singing jingles. Nik Brown’s mother was a concert pianist. During his days at Cambridge University he played violin in a string quartet floating along on a punt, and with Hot Café he played Django Reinhardt/ Stephane Grappelli jazz in Wellington for three years. Rob Clarkson won a lottery and went to New York to study jazz drumming. And John Donoghue was a member of Timberjack, who reached the finals of the Loxene Golden Disc with their satanic ‘Come to the Sabbat’.

“I come from the hobby school,” says Mason. “Music was a hobby, something you do to alleviate the stress of other things. To be a professional musician was unheard of in the 50s in Taranaki when I grew up. You had a job, and didn’t expect to earn a living out of it.”

Saunders laughs. “I’ve always expected to get a living out of it, and thought it perfectly reasonable.” Waka Attewell, a friend of the Warratahs, filmed them in Gore for a documentary, and the legendary Southland country band The Tumbleweeds got up to play with them. “It was amazing," says Saunders. “They’re all quite old now, and they play real straight country, a ‘Maple on the Hill’ sort of feel. Cole Wilson played steel and violin.

“It’s funny, because I think Cole’s around 70, but he’s still an entertainer. He’s really dressed up, and he has a sort of aura, and he likes to be taken seriously and be respected. Usually entertainers give up to go into business or have families. But Cole’s still, I imagine, the same as when he was 30. We’re all a bit like that – don’t you think?”

“What?” replies Mason. “Doing this forever? Entertaining people? Yeah – there’s nothing better really. Some tracks on the album I listen to and I still get a tingle, oooh, that’s really nice, that. Just the same feeling I got when I was nine or 10.

“I’ve arrived after how many years? 25 years? To be playing exactly how I love to play. Which is probably the beauty of this band. Everyone loves what they’re doing best of all.”

--