Moetū Haangū Ngāwai was born on 5 May 1910 in Enihau, just north of Tokomaru Bay on the North Island’s East Coast. Her parents were Te Rā Haangū Ngāwai, a farmer, and Te Ipo Hārata Te Awhi Kaahi Parata (both Te Whānau-a-Ruataupare of Ngāti Porou). The couple already had six children when Te Ipo found she was pregnant. She went to the tohunga of the Ringatū church to receive a blessing, and was told that the child was going to be gifted as a leader. Te Ipo later found she was carrying twins, and wondered which of them would show the leadership qualities predicted.

Two girls were born: the first was named Moētu Haangu, and the second Te Huinga. Sadly, Te Huinga died after 12 months. To remind Moētu that she was a twin, and to honour Te Huinga, she was named Tuini (twin).

Tuini’s father died when she was 12, disappointed that the special talents foreseen by the tohunga had yet to emerge. Two years later, Te Ipo died, but she was able to witness Tuini writing her first song, which Te Ipo set to music. It was a love song, and all were impressed by the poetry of the words.

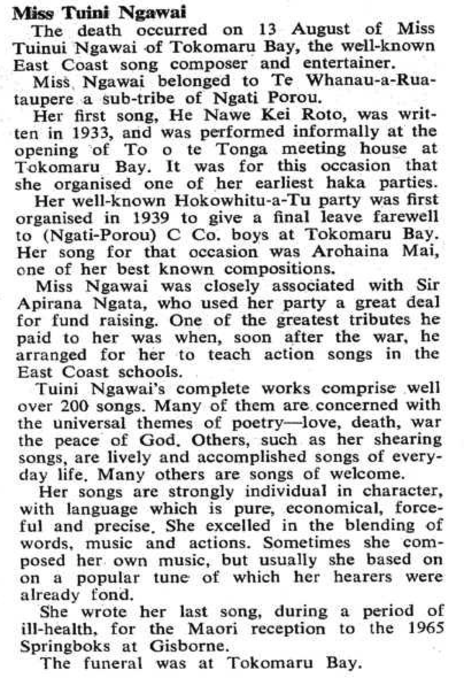

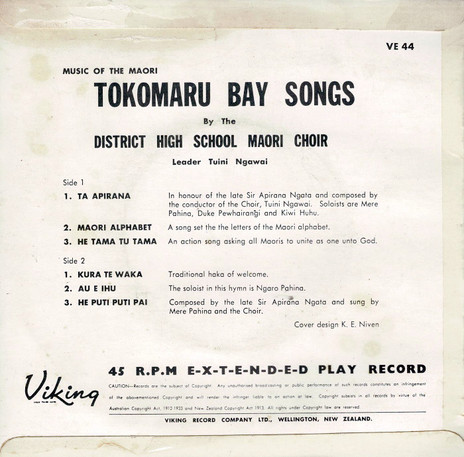

Most of Tuini’s songs, writes Anaru Kingi Takurua, are “spiritual in their inspiration, but each written for a specific, often pragmatic purpose.” The subjects she chose were common to most poetry: love, death, war, and the peace of God. She also wrote about everyday life, especially in her many shearing songs. Some have specific Māori subjects, and her many welcome songs are used extensively by action groups and in kapa haka long after her death in 1965.

Sir Āpirana Ngata was her earliest champion. He heard her song ‘He Nawe Kei Roto’, written when she was 20, asked her to sing it for him, and then told her to sing it at the opening of the carved wharenui Te Hono ki Raratonga, at Tokomaru Bay. The song soon became well known throughout Ngāti Porou, and Tuini became dedicated to writing Māori songs. Others written in the late 30s include ‘Awhitia au’, ‘Mā te Aha Rā e Tama’, and ‘Mai Ngā Rā o Mua e Ari’ (the latter was about the Lady Arihia Ngata hockey trophy; Tuini was a keen player and coach, with many successes).

Tuini moved to Auckland in 1939 and joined the choir of Walter Smith, well-known teacher of stringed instruments, and leader of his own jazz bands, choirs and string orchestras. Smith was also a songwriter, whose best-known song ‘Beneath the Māori Moon’ was recorded by his cousin, former All Black George Nepia, in the UK in 1936. Although in Auckland only briefly, Tuini took part in many broadcasts with Walter Smith’s choir, and he “gave her grounding” in musical composition. She wrote the Māori words for many of the choir’s songs.

In late 1939 Tuini returned to Tokomaru Bay, to help with the Māori war effort led by Sir Āpirana Ngata

When the Second World War broke out, Tuini returned to Tokomaru Bay, to help with the Māori war effort led by Ngata. As with the First World War, Ngata saw Māori participation in the war as a step towards being regarded – and treated – as full citizens. “After the war,” wrote historian M P K Sorrenson in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, “Ngata never lost an opportunity to remind Pākehā New Zealand of the debt the country owed to Māori who had served or died in the empire’s foreign war.”

Ngata was a visionary, determined to improve the health and welfare of Māori, and emphasised the importance of culture and language to this goal. A songwriter himself, he had a scholarly interest in Māori music, but saw the benefits of a modern approach. Combining Western culture – for example using popular melodies – with te reo would strengthen Māori culture when it was under dire threat. Popular songs could convey the messages that suited his goals.

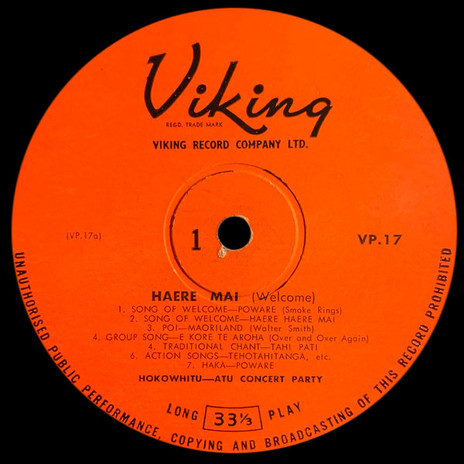

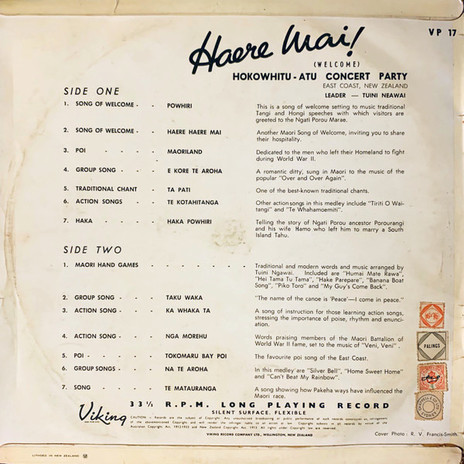

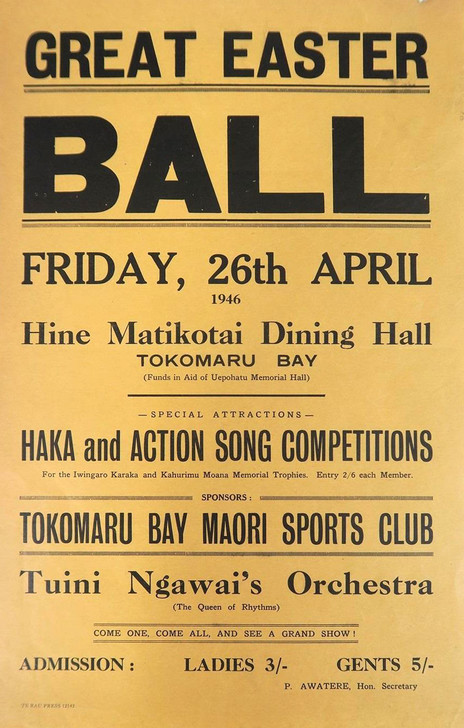

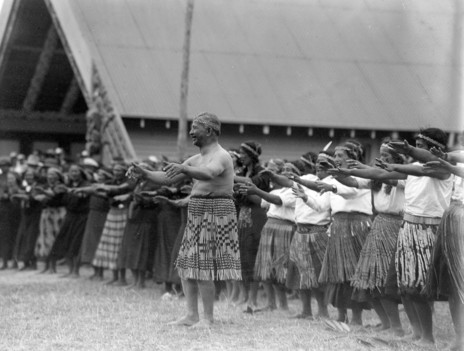

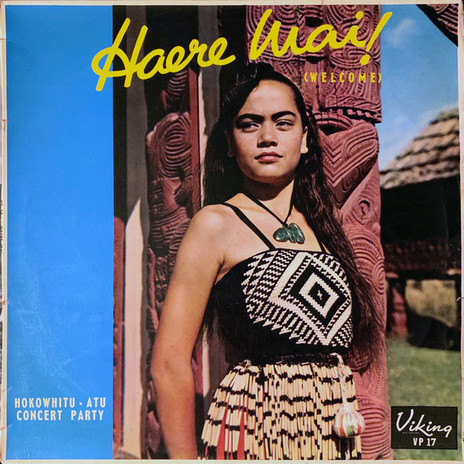

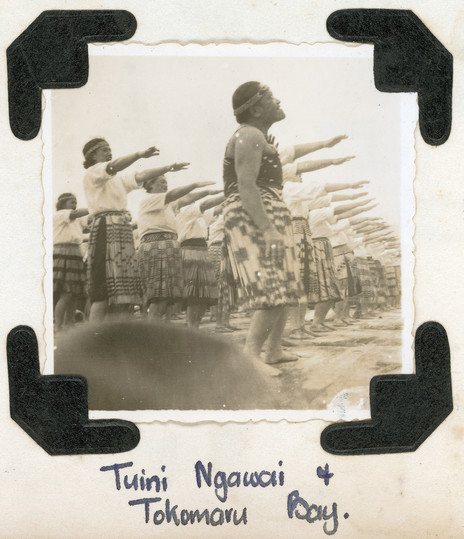

Tuini formed and led Te Hokowhitu-a-Tū, a performing arts group that helped Ngata in his recruitment campaign for the 28 Māori Battalion. In this period she wrote many songs which became famous and a perennial part of the waiata repertoire, through being heard in training camps and farewells, in homes and on marae. Among these were the farewell ‘Haere rā e Roa’ (written for her sister Materoa, who had joined the army), and ‘Arohaina Mai’ (“regarded by many as her masterpiece,” writes Takurua). Also among her many wartime songs were ‘Te Hokowhitu-a-Tū’, ‘Ngā Rongo’, ‘Pāmamao Ana’, ‘Kaure Mōkai’, ‘Horahora’, and ‘Haera rā te Aroha’.

In 1943 Ngata, the Māori Development Minister, recruited Tuini to be a teacher specialising in Māori culture, and she visited all schools that had Māori pupils, from Te Karaka to Whangaparāoa. She was central to the hui that year which celebrated the award of the VC to the late Te Moananui-a-Kiwa Ngārimu. She taught masses of school children to perform ‘Karangatia rā’, written by Ngata to mark the return of Māori troops from the First World War.

‘Arohaina Mai’ became regarded as the “unofficial hymn” of the Māori Battalion. It was written after a farewell service to the troops of the Battalion’s C Company: East Coast men from Gisborne up to Te Araroa. The service was a huge event, the Waiparapara marae at Tokomaru Bay inundated with people. Tuini recalled that on her way home, overcome by emotion, she took a rest by the road. The words of ‘Arohaina Mai’ came to her, complete, and she wrote them down immediately. The melody was George Gershwin’s ‘Love Walked In’.

Sometimes Tuini wrote her own music – for example, ‘E Nga Rangatahi’ – but mostly she used existing melodies, often from Western popular songs which her singers could memorise quickly. It was the message of the words that mattered most; the tune was merely a vehicle to carry the words.

“She rarely changes these melodies and ingeniously fits her words to the existing music,” an uncredited profiler wrote in the April 1956 Te Ao Hou. “Very often the words are incomplete without the actions. This is not because the poet could not find more expressive words, but because the actions adequately convey the feeling.

“A strong individual character runs through all the songs and it is no accident that her party was called Te Hokowhitu-a-Tū. A war-like strength is evident everywhere; the attitude to pain and misfortune is perhaps peculiarly Māori, certainly different from most European poetry – pain is not described, analysed or escaped from, but fought like an enemy.”

Did her use of popular hits show a lack of originality, the Te Ao Hou writer asked. “If one compares the original song ‘Love Walked In’ with ‘Arohaina Mai’, the spirit is entirely changed although the tune is still about the same. Obviously Tuini Ngāwai only uses the popular hit because it suits her purpose, not because she is forced to lean on it.”

Shortly after the war, Tuini left her teaching role and became a supervisor with the shearing gangs in her community. This played to several of her strengths: her abilities as a teacher and a motivator, and her skill at songwriting which helped bond the shearers, fleecos and roustabouts after hours. The melodies may have been hits such as ‘Goody Goody’ and ‘In the Mood’ (‘Te Hokowhitu-a-Tū’), but they encouraged the use of te reo, and a feeling of community and kaupapa noa.

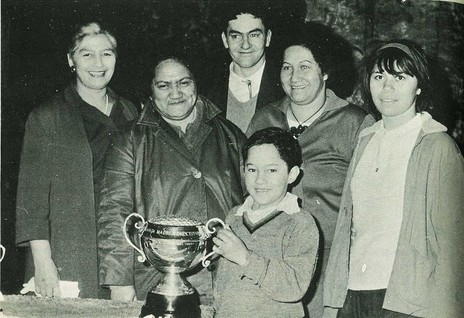

Tuini’s reputation as a perfectionist was also visible in the shearing sheds, teaching novices in all aspects of the craft. She led by example and in 1961, aged 51, she won the women’s section of the Golden Fleece Contest. Falling behind her competitors on the boards, her niece Ngoi Pēwhairangi began to sing one of Tuini’s own shearing songs, changing the words to say that a favourite was losing ground. Others in their group took up the song and Tuini was inspired to pull ahead to victory.

As a leader, Tuini’s standards were high, and she had a biting tongue when they weren’t met. “Somehow Tuini got away with it,” states the short biography in Tuini: Her Life and Her Songs (Hokowhitu-a-Tu, 1985). It was her manner, and part of her leadership style. But “partly it was because everyone who worked with her knew that all she did was for their benefit, and most of all it was because, in spite of her strictness, she was a person full of fun who kept the shed rollicking with the endless shearing songs, full of topical allusions, and caustic references to everyone in the gang, including herself.”

Tuini wrote many shearing songs that are regarded as some of the finest Māori folk songs

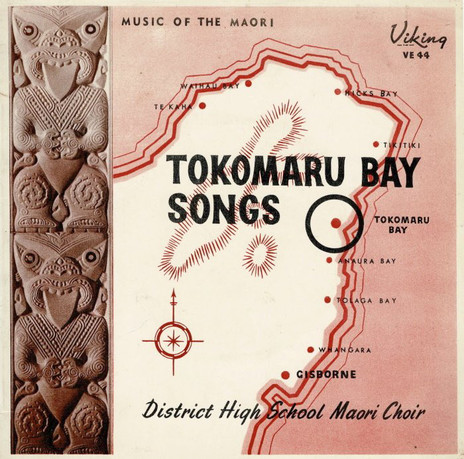

Tuini wrote many shearing songs that became standards on the East Coast, and are regarded as some of the finest Māori folk songs. Whereas her war songs were poetry, emotive, and spiritual, the shearing songs were written to entertain, to relieve the monotony of shearing; they were also gently satirical of the characters found in the gangs. Besides their entertainment value though, they “contained an inner code of meaning which only those immediately associated could follow.” Among the songs, many of which combined Māori and English and remained popular for decades, were ‘Kei Tangi a Big Ben’, ‘What a Dopey Gang’, and ‘Hūpeke Gang’ (and ‘It's Now or Never’ became ‘It's Shearing Season’). Because they were set to light-hearted Western melodies, Pākehā audiences often missed the serious messages.

“When the gang was gathered at nights around the piano, or a guitar, having a sing-song, Tuini would improvise a song to some topical tune and proceed, in her inimitable way, to give valuable hints to shearers and fleecos, her instructions interspersed with caustic comments on the faults and frailties of all concerned.”

In the post-war years, Tuini often led her own six-piece band, the ATU Orchestra, playing saxophone herself or a variety of other instruments. During the 1953-54 royal visit, Te Hokowhitu-a-Tū and Tuini sang her song ‘Te Tiriti o Waitangi’ in front of of Queen Elizabeth 2. Two years later, she wrote ‘Nau mai, haere mai’ to welcome the South African rugby team to Gisborne.

The book Tuini: Her Life and Her Songs, which also contains many of her lyrics, was compiled by her niece and companion in music, Ngoi Pēwhairangi. It describes Tuini as having authority that was “absolute. Her knowledge, whether it be shearing, marae etiquette or Māori tradition was irrefutable.”

Tuini Ngāwai died of cancer in 1965, and was buried at Ngaiopapa, Tokomaru Bay. Anaru Kingi Takurua writes that she “left behind a rich legacy of songs and an unsurpassed standard of composition, work and community leadership.”

What is her legacy beyond the East Coast community, and the kapa haka movement? Ngoi Pēwhairangi went on to write the words ‘E Ipo’ for Prince Tui Teka, and ‘Poi E’ for Dalvanius. Both were No.1 hits. Dalvanius told me in 2002, “No Māori apart from my aunty [Pēwhairangi] and Tuini Ngāwai were in the fore of music: it was all a house-to-house, marae-to-marae musical industry. That’s how Māori music was kept alive. Because there was no radio programme playing full-language Māori language records. Tuini Ngāwai would take a song like ‘Goody Goody’ and the next minute, she writes new words to it. She’d take a popular song which Māori loved in its English equivalent – whakamāoritia ki te reo Māori – which means translate it into Māori.”

Rob Ruha is one of several contemporary Māori musicians who looks to Tuini Ngāwai as a mentor. “I consider her to be a master in composition,” he told Hira Nathan of Mana magazine in 2015. “The way she blends music and lyrics in a simple and straight-forward way heavily influences how I compose my music …

“I think the messages that Tuini has handed down have given us the ability to celebrate our own unique identity in a contemporary world and a world where we can comfortably sit and be us.

“The things that Tuini has handed down have been a cornerstone to my success in the music industry and on the kapa haka stage. It comes from the old adage, ‘A tree is strong when its roots are strong.’ If I had different roots I would be a different tree. The things that I do, they come from my bones, from my soul, from my ngākau and those are the things that have made me who I am.”

In 2004 Paul Diamond of RNZ made a moving two-part Musical Chairs documentary on Tuini Ngāwai which is the best place to understand her work and its legacy. He talks to many who knew her: whānau, kapa haka pupils, singers from shearing gangs. He writes that, besides her work in music and teaching Māori culture, “She also involved herself in the Kotahitanga movement with a strong determination to restore Māori pride and identity alongside efforts to achieve greater recognition for the Treaty of Waitangi. As always, she had meaningful messages to convey about these kaupapa through songs such as ‘Te Kotahitangarā e’.

“Her invaluable contributions to kaupapa Māori through waiata and performance formed paths for following generations to continue uplifting the culture through music.”

--

Sources

Anaru Kingi Takarua, ‘Ngāwai, Tuini Moetū Haangū’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, 2000

Ngoi Pēwhairangi, Tuini: Her Life and Her Songs, Hokowhitu-a-Tu, 1985

Obituary, Te Ao Hou, December 1965

‘Tuini Ngāwai’, Te Ao Hou, April 1956

Hira Nathan, “Ko Wai Koe? Who Are You? – Rob Ruha’, Mana, June/July 2015

Recommended listening

Musical Chairs: Tuini Ngāwai, produced by Paul Diamond for RNZ, 2004