Her compositions were often written spontaneously or commissioned for specific events such as the first royal visit by Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh to Gisborne in 1954, the Cook Bicentennial commemorations in 1969-70, and the royal visit of Prince Charles and Princess Diana in 1983, where she was responsible for organising the final pōwhiri.

In his book Being Pakeha, historian Michael King wrote: “Although Ngoi Pēwhairangi valued and practised humility above all other qualities (she always entered her marae, Pakirikiri, through the back entrance), no individual on the East Coast since Āpirana Ngata had attracted more mana. She organised her own community with quiet authority and her people would have done literally anything for her. She was the greatest composer of modern Māori music, having inherited this mantle from her aunt, Tuini Ngāwai.”

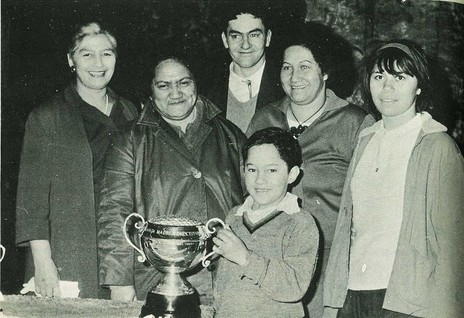

Te Kumeroa Ngoingoi Ngāwai was born on 29 December 1921 at Tokomaru Bay, the eldest of five children of Hori Ngāwai and Wikitoria Te Karu of Ngāti Porou descent.

She attended Tokomaru Bay Native School from 1928-1935, at a time when such schools were used as part of the government’s assimilationist policies for “Europeanising” and “civilising” Māori.

Kapa haka advocate

While Ngoi’s first language was te reo she quickly became literate in English, winning a scholarship in 1938 to attend Hukarere Māori Girls’ School in Napier where she studied until 1941.

Ngoi was accomplished at hockey – competing with the Marotiri team of Tokomaru Bay in school tournaments around the North Island – but it was the kapa haka performing arts components of these engagements that saw her in her element.

While working in a shearing gang she was known for her mischievous nature and her singing.

While working in her aunt Tuini Ngāwai’s shearing gang she was known for her mischievous nature and her singing. On one occasion, when her aunt was competing in a shearing competition, Ngoi spontaneously burst into song to inspire her to pick up the pace when she was lagging behind.

Tuini Ngāwai formed Te Hokowhitu-a-Tū Concert Party from the Marotiri sports group and from 1939 began travelling around New Zealand entertaining and raising funds for the war effort. Accompanying the group was Ngoi, who Ngāwai was grooming in performance, composition and leadership.

Ngāwai was respected for her marae etiquette, and knowledge of Māori laws, customs and traditions, and took a strict approach to those who were part of her performing arts group. Fellow performer Keriana Pōhatu recalled Ngoi liked to have fun: “We were to stand properly, not to giggle and laugh, but Ngoi used to sneak to the back and giggle behind us. We thought it was quite funny.”

As Ngoi took on more responsibilities she decided on a more compassionate style of teaching kapa haka. Ngāwai had been very strict about things like footing and would “whack you with a stick if you didn’t have your foot right”, whereas Ngoi would offer verbal correction, something she later became known for.

In 1943 Sir Āpirana Ngata appointed Ngāwai as a teacher of Māori culture and later that year she and Ngoi performed a waiata-a-ringa at the posthumous investiture of a Victoria Cross to Second Lieutenant Te Moananui-a-Kiwa Ngārimu. The function, at Whakarua Park, Ruatoria, was attended by 7000 people.

Ngoi met and married fellow Tokomaru Bay shearer Rikirangi Ben Pēwhairangi in 1945. The couple continued to work on the East Coast shearing circuit. Ngoi and Ben had one son of their own, Terewai, but raised many others including their own grandchildren.

On Ngāwai’s death in 1965, Ngoi took over running Te Hokowhitu-a-Tū, remaining an integral part of the group for the next 20 years.

Cultural revival

Ngoi Pēwhairangi was a key figure in passionately promoting and rebuilding Māori confidence in their own art, culture and crafts.

Ngoi Pēwhairangi was a key figure in rebuilding Māori confidence in their art, culture and crafts.

In the early 1970s she was a foundational supporter of Ngā Puna Waihanga (Māori Writers and Artists Association) and later in the decade was appointed to the Māori and South Pacific Arts Council, representing Tairāwhiti.

For three years from 1973, she taught at the Māori Club at Gisborne Girls’ High School and began tutoring in Gisborne for the University of Waikato’s continuing education certificate in Māori studies.

Her skill in motivating people of all ages and ethnicities was recognised within Māori educational circles and in 1977 she was asked to help put together the Tū Tangata programme, to reconnect alienated urban Māori youth to their iwi. Also in 1977, in Wellington, she gave a lecture “The Māori concert party as an art form” as part of an exhibition and demonstration of Māori crafts from the Tauira Crafts Centre, Tokomaru Bay.

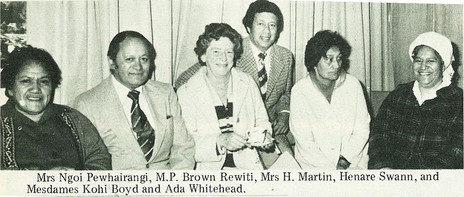

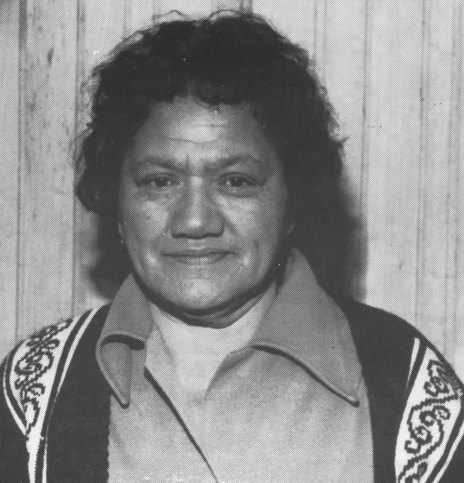

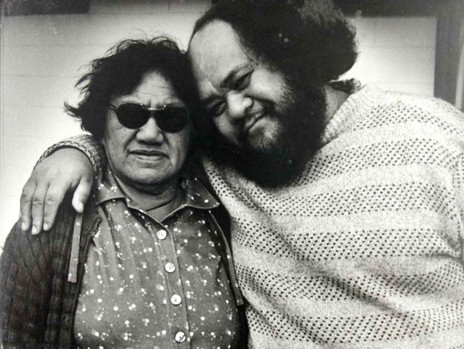

Broadcaster Henare te Ua describes her in The Book of New Zealand Women: Ko Kui Ma Te Kaupapa as “a rather shortish woman … fairly well built”. Her trademark was the dark glasses she always wore. “Ngoi had that lovely way of always tossing back her head … and [her] glasses would lift like her eyebrows. You never really saw her eyes, so you couldn’t tell what she was thinking about.”

He says Ngoi had “tones of voice” depending on what the occasion was. “I know she used to startle different audiences. Here was this respected and dignified person, coming on stage, head held back. People would whisper, here she is, and Ngoi would just get the mike [sic] and say, Talofa lava! Everyone would just burst with laughter, because they expected some great tauparapara [oratorical chant]. She used to rock people. But this is part of what I would call Ngāti Porou humour.”

Te Ua wrote that after the "spectacular” royal welcome for the Queen and Duke of Edinburgh at Rugby Park, Gisborne in 1970, where all the tribes were represented, “a lot of people asked why do we wait until Pākehā royalty arrives before we do this sort of thing? Why perform to the best of our ability only for Kuini Pai [Queenie Pie]? Why don’t we have cultural competitions on a regular basis?”

Out of that discussion emerged the New Zealand Polynesian Festival from 1972; this became a biannual event with Ngoi as one of the judges, her particular expertise being the waiata.

Advice in demand

In 1979 when the festival was held in Lower Hutt, after a pregnant pause while everyone was waiting to see who had won, Te Ua says Napi Waaka the MC called for Ngoi to come out and he began singing a pop standard, ‘You Always Hurt The One You Love’. “He paused at the end of every line and in impeccable te reo Māori, Ngoi would come in and translate, just adding extra emphasis on certain words, to bring out the meaning. Well the place just packed up.”

Also in the 1970s Ngoi became script writer and advisor for Te Reo, the Māori language programme TV series, and assisted Michael King with the development of the Tangata Whenua TV series.

In 1978 Ngoi Pēwhairangi received the Queen’s Service Medal (QSM) for her services to the Māori people.

Ngoi was involved in discussions that led to the kōhanga reo movement and as part of the National Council of Adult Education promoted cottage industry crafts such as pottery and weaving along with teaching te reo and culture.

As a tribute to her aunt, Ngoi compiled Ngāwai’s songs, and these were published in Tuini, Her Life and Her Songs (Te Rau Press, Gisborne, 1985).

Ngoi remains best known for her collaborations with contemporary musical pioneers.

While widely respected for her immense contribution in restoring Māori arts, crafts, cultural performance and language, Ngoi remains best known for her collaborations with more contemporary musical pioneers.

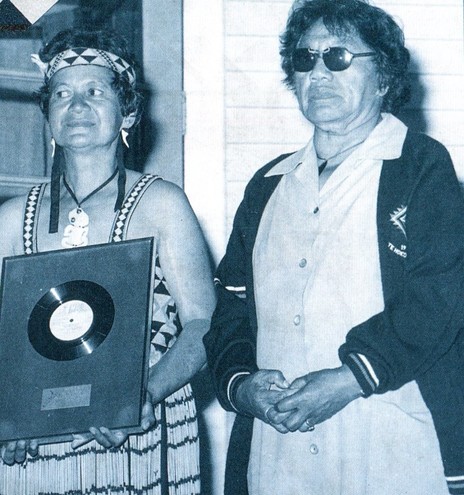

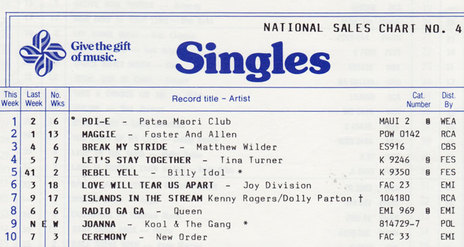

She wrote the lyrics to Prince Tui Teka’s ‘E Ipo’ – a gold record selling 7500 copies – and ‘Poi E’, by Dalvanius Prime and the Pātea Māori Club, which earned triple platinum status for selling around 20,000 copies.

Chart-bound love

Prince Tui Teka was introduced to Ngoi when he was courting her niece Missy, who later became his wife. His greatest hit, the 1982 recording of ‘E Ipo’ – although based on an Indonesian folk melody – was a love song to Missy, with lyrics translated by Ngoi.

It became part of the 1980s cultural renaissance in which songs using te reo achieved high positions on the music charts; other early examples were Dean Waretini’s ‘The Bridge’ in 1981 and Howard Morrison’s version of the hymn ‘How Great Thou Art’ (‘Whakaaria Mai’) in 1982.

‘E Ipo’ was produced by Maui Dalvanius Prime, from Pātea in South Taranaki, who after his own music success on both sides of the Tasman, created his own record label to encourage a Māori Motown.

After winning a talent quest on Wellington’s radio 2ZB, he joined Porirua vocal trio The Shevelles as their pianist/arranger, before forming the Fascinations and touring throughout Australasia. They were in high demand.

On returning to New Zealand, Dalvanius was determined to share what he learned about the music and recording industry with up and coming artists. “When I was starting in music,” he said, “all my idols were American black musicians.” His goal was to make it possible for “Māori kids to have Māori idols”.

After his success with ‘E Ipo’, Dalvanius produced ‘Maoris On 45’ by The Consorts, a medley of songs that were perennially popular at Māori parties. It was produced in the style of international No.1 ‘Stars On 45’, which became an unexpected hit in 1982. “When our parents had parties at home we would bring out the ukulele and sing our Māori medley … When it got to No.3, I nearly dropped dead.”

Dalvanius collaboration

In a September 1986 Rip it Up interview Dalvanius told Chris Bourke that he became connected with Ngoi Pēwhairangi through Prince Tui Teka. “Of course, I’d always heard songs like ‘Haere Mai’ and ‘Paikea’ ... on the marae, you hear every cultural group from Ngāti Porou perform them.”

He met with Ngoi at her Tokomaru Bay home around the time Tui Teka’s ‘E Ipo’ was riding high in the charts. “She had gumboots on and she was the most unassuming, unpretentious woman I’d ever met and she ... reminded me very much of my mother really, only shorter.”

They agreed they would like to write together. “I said I’ve got heaps of damn tunes and no words,” said Dalvanius, who had to get back to Wellington Polytechnic to attend a Māori language course within two days. Ngoi convinced him to stay and attend “the best school of all, the Wānanga of Ngāti Porou”.

Ngoi’s husband Ben knew their lives would never be the same the day Dalvanius walked into their home. “She was the tutor; her student wide-eyed and eager to learn about Māoritanga. I recall their days and nights together … immersed in their work, oblivious to the existence of anyone else.”

The idea for a musical arose when Ngoi took Dalvanius to the old Tokomaru Bay freezing works where all the walls had fallen down. “We had this incredible affinity with each other because of what had happened at Pātea.”

Ngoi, a Ringatū priest, insisted they have a karakia (prayer) before beginning work. “Then we would get into the project and we never pondered over anything that she wrote. She would say, ‘What shall we write this song about?’ and she would give a kaupapa, and I would give her the tune and I’m telling you, she wrote it once and once only, right to the phrasing.”

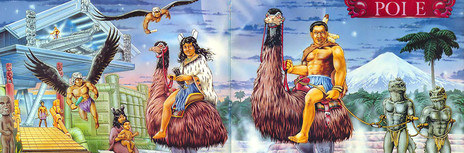

The bulk of ‘Poi E’, the extended musical and all of the Pātea Māori Club songs, were composed in four weeks. Dalvanius took the songs home, rehearsed three, and entered them in the Aotearoa Performing Arts Festival in Hastings, winning the best poi for ‘Poi E’ and best action song for ‘Hei Konei Rā’; along with ‘Aku Raukura’ the club won the audience over.

Generational challenge

Ngoi, however, took a lot more convincing. The only song she liked was ‘Hei Konei Rā’ which was very predictable and “John Rowles-ish”, said Dalvanius. She didn’t like ‘Poi E’ but he challenged her to play the songs on cassette to her mokopuna (grandchildren) and also gave her a copy of the ‘Poi E’ video.

“It was outrageously radical; barefooted Māori and their kids rolling around on roller skates doing the poi, the long poi, and bop dancers bopping and trying to recreate a little concert at the Pātea High School [showing] all these kids screaming to the Māori language and it was all totally contrived … to market the single.”

Then Ngoi confessed her mokopuna loved it. “They won’t take it out of the VCR! They play it up loud and they're doing the poi’s to it.”

Dalvanius told Ngoi ‘Poi E’ would be a No.1 hit, because she hated it and the kids loved it.

Dalvanius told Ngoi it would be a No.1 hit, because she hated it and the kids loved it. However, she warned that he would shake up the industry and would likely make enemies.

“I said you’re the one who gave me the challenge, how do we make our language accepted by the younger generation? … I said, guess what … the next generation of Māori kids are going to like ‘Poi E’ and they're going to suck it up because a Māori culture group barefoot with a whole lot of boppy kids are going to be their new heroes instead of Michael Jackson.”

The Pātea Māori Club effort was produced and managed by Dalvanius on his own Maui music label, with 29 Pātea businesses donating $100 each to pay for the recording costs.

Despite support from Mascot Studio owner Hugh Lynn and Tim Murdoch of WEA Records, it was largely ignored by New Zealand radio stations until a TV news story awakened interest, sending the song steaming up the charts.

Song keeps giving

The Pātea Māori Club was invited to tour the United Kingdom, playing at the London Palladium, the Edinburgh Festival and a Royal Command Performance.

UK music magazine NME rated ‘Poi E’ as “single of the week” in February 1985 when the Pātea Māori Club were playing New York’s Irving Plaza with the Violent Femmes. In New Zealand the single spent four weeks at No.1 and 22 weeks in the charts and was followed by an album in 1987.

The success of the Pātea Māori Club helped bring some light relief and a restored sense of identity to a small town devastated by the closure of its freezing works in 1982.

Club secretary Patricia Ngarewa said on the 30th anniversary of the hit that the song's success repaid the faith musician and composer Dalvanius Prime and Māori linguist Ngoi Pēwhairangi had in their song. “Dal always used to say te reo, te reo, te reo, we must not lose our language.”

In 2000 Dalvanius Prime handed over the rights for 23 songs he co-wrote with Ngoi Pēwhairangi to her family. He died of cancer on 3 October 2002.

In 2009 ‘Poi E’ was back in the charts following a Vodafone promotion, and it re-entered the charts again in 2010 after it inclusion in the Taika Waititi movie Boy, reaching the third spot on the Top 20. It is the only New Zealand song to chart in three separate decades.

In July 2016 a documentary feature about the song, Poi E: The Story of Our Song, written and directed by Tearepa Kahi (Mt Zion), premiered at the New Zealand International Film Festival.

Memorable contribution

Two of Ngoi Pēwhairangi’s songs are featured in the APRA Top 100 New Zealand Songs of All Time, ‘Poi E’ at No.37 and ‘E Ipo’ at No.81. In 1994 the Variety Artists Club awarded a Scroll of Honour to the Pātea Māori Club and in 2016 she was posthumously granted the club’s Nostalgia Award.

Ngoi died on 29 January 1985, at her home at Tokomaru Bay, after a long illness.

Tania Ka’ai wrote in Pēwhairangi’s Dictionary of New Zealand Biography entry that Ngoi was revered for her unrelenting work for the advancement of the Māori language and culture “and the development of her ideal of a bicultural nation in which Pākehā would help to ensure the survival of the Māori language”.

Henare Te Ua says the song which encapsulates the essential Ngoi, is ‘Ka noho au i konei’, “where she sits and ponders, wondering what on earth is happening to us as a people these days. Where are we going to? Who are we turning to? What will become of our youth?” While it’s a song full of questions, Te Ua says the answers are there also in this “epic poem”. He says the song is all the more poignant because it was written when “she was reaching the twilight of her years.”

--

Resources:

Ngoi, A Remarkable Life, Tania M Ka’ai, Huia, Wellington, 2008, pp 8-12

New Zealand Women Ko Kui Ma Te Kaupapa (Bridget Williams 1991), pp 516-518