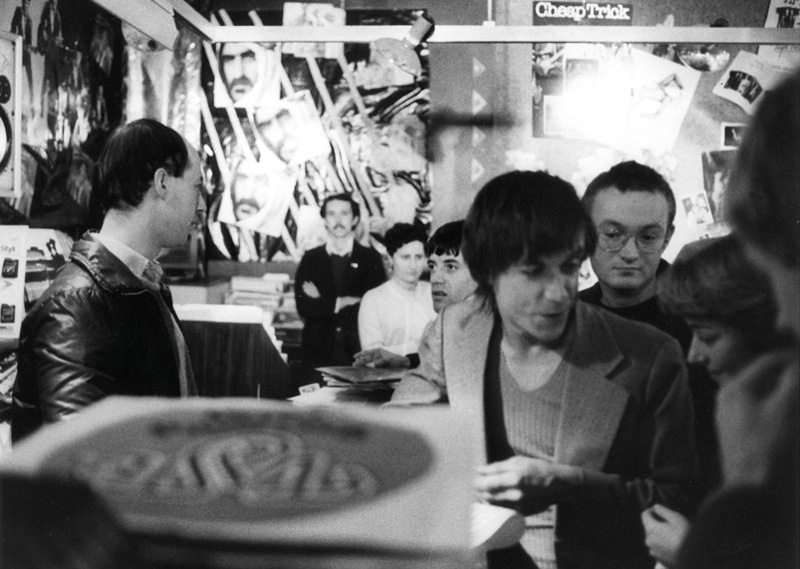

The Windsor Castle, March 8, 1980. The band is a mix of Toy Love, The Androidss and The Spelling Mistakes - Photo By Sara Leigh Lewis

Many of the great punk performances in Auckland didn’t happen at night, but in the afternoon.

Daylight. The Windsor Castle on Parnell Road. The sun barely screened out. Crowds queuing for jugs of beer. Chris Knox contorted on the stage, cutting his arm with a broken beer bottle, red blood following the brown bottle’s gouging – “I don’t feel any pain/but the doctors say I’m clinically insane …” – in front of an audience taking it with a cool, seen-everything attitude.

It was exactly what the punters had come for, something real.

Parnell, 1978. Sun-blasted Saturday afternoon suburban streets. Unrenovated houses with flaking white paint and backyards strangled with morning-glory. The long slope of Parnell Road, raffish and empty in the afternoon heat. Billboards for the evening Auckland Star and the 8 O’Clock outside the dairies. Cracked pavements on Birdwood Crescent.

The Windsor, March 1980 - Photo By Sara Leigh Lewis

Larry Young and Fiona Grigg were the bookers for the Windsor Castle. It was the first of the established venues to begin booking punk bands from late 1977/early 1978. Daylight notwithstanding, The Enemy (the first incarnation of Toy Love), Toy Love itself, The Terrorways, The Aliens, The Superettes, Proud Scum, and The Scavengers (who played the Windsor Castle NYE 1977/78), all performed the matinee shift in the afternoons of Auckland punk. Later in the evening, they’d be followed by Street Talk, Th’ Dudes or Citizen Band for the venue’s more conservative night crowd.

The Windsor closed at 11pm. Beers were on tap, 62 cents a jug. A pack of Winfield 25s was 64 cents and they could be smoked inside, ashtrays on tables. Boot girls close to the stage, in a tight group, their styles later to be transformed and recycled to the next century’s English haute couture, but presently op-shop stuff chosen with discrimination and particular taste. Neat suburban boys in their weekend punk at the back of the venue, ripped T-shirts and passé safety-pins. Black visored military caps. Yvette Parsons in go-go boots and a vinyl skirt. Adolescent acne worn with a scowling flourish. Straight-legged trousers. Gym-shoes or army boots. Art-school mingling with dole-queue. Proud Scum’s Beagle Boys sweatshirts. Nick Hanson of The Spelling Mistakes slowly stripping down on stage, mid-song, to reveal white Jockey undies. Fingerless gloves. White shirts with torn-off sleeves. Black eyeliner or butterfly-wing smear. Pinned pupils from cheap heroin. And all so very, very young.

XS Cafe - Photo by Bryan Staff

For two or three years, punk bands popped up like mushrooms on a Waikato farm.

The music ranged from basic chords to more complex structures. It was energy with a nihilistic edge. It sported a New Zealand accent that was as unmistakable as ‘Rena’s Pissflaps’. It had imported a genre and re-tuned it to Kiwi tastes. For two or three years, punk bands popped up like mushrooms on a Waikato farm. They caught the edge of a decade that saw New Zealand plunged into economic mire and a whole generation leave for offshore. There was no depression in New Zealand. Yeah, right.

At one extreme, there were The Idle Idols, possibly Auckland’s most beautiful band, definitely its worst players. For their single Windsor Castle afternoon appearance they played one song, Roxy Music’s ‘Editions of You’, where Sandra Jones vocalised the synth parts, with Jamie Jetson on lead, Leonie Bachelor on bass, Paul Gibbs on vocals, before failing to cohere for their second song and simply walking off the stage. The Idle Idols were impossible glamour: eye-make up had taken hours, cheekbones were sculpted in powders, lips shaped with glosses. Musical inability was compensated for by anarchistic girl-power.

At the other extreme was Toy Love. Out of Dunedin and Christchurch, Toy Love expertly led the second wave of New Zealand punk, after Suburban Reptiles and The Scavengers. Hanging just this side of psychopathy in his performances, Knox patrolled the risers of the Windsor Castle stage like a possessed man. Jane Walker on her Ekosonic keyboard added a crazed poppy layering to the Shakespearean sturm-und-drang. Alex Bathgate and Paul Kean on lead and bass, and Mike Dooley on drums maintained the backup energy for Knox to twist and derange and turn upon the audience. He walked on tables. He hit the floor. He cut himself. He hurt. He sang.

Toy Love's Mike Dooley steps out - Photo By Sara Leigh Lewis

Just as in wartime, people had their nom-de-guerre. Real names had been tossed in favour of a punk alias. Zero, Suburban Reptiles' lead singer entering with near-Nazi bleached-blonde hair. Mike Lesbian with gaudy food-colouring through his bleach. Johnny Volume. Billy Planet. Buster Stiggs. Ronnie Recent. Jamie Jetson. John No One. Jonathan Jamrag. John Atrocity. Ko. Twitch. Real names were a secret thing. Some punk names would stick to an individual for the rest of their lives. Some would remain a near-forgotten ballpoint scrawl on the back of a fading pic in a photo album.

Simon Grigg with Iggy Pop at Taste Records. Writer David Herkt is to Iggy's left. At the back wall is designer Terence Hogan (AK79, Class of 81, Toy Love etc.). Peering over Iggy's shoulder is future Oscar winner Kim Sinclair – photo by Chris Slane

Financially, New Zealand was a mess. Muldoon and a quick switch back to Labour and back to National again had plunged the country into economic chaos. Music from the punk heartland of the UK was hard to get, New Zealand’s precious remaining overseas currency reserves were guarded ruthlessly. Getting a postal order to send away to a company that advertised in the back-pages of a three-month-old copy of NME was a major bureaucratic mission. Forms had to be filled in. Larger postal orders required government approval. Like petrol, new records were rationed.

There were a few record shops with well-watched import sections that could provide an album whose possessors would gain instant prestige because of its relative unobtainability. But attitude could conquer everything. One punk party in Freemans Bay survived on a 45-rpm single of Sandie Shaw’s ‘Puppet on A String’ played on repeat for the entire night. Gesture replaced content.

The Windsor Castle, March 8, 1980, with Toy Love - Photo By Sara Leigh Lewis

Music shops were a lifeline to a greater world. Iggy Pop, on a promotional tour in July 1979, signed records in Taste Records in High Street. He attended the annual Cook Street Market party in the Mandalay in Newmarket and briefly dated a trannie-boy. In Parnell, future music-entrepreneur Simon Grigg worked in Taste Records’ Parnell shop, on the other side of the road from the Windsor. It provided an easy stop, a place where new music could be shared and heard, events previewed and analysed.

The power poles along Parnell Road were wrapped with gig posters made by every available means of reproduction, from linocut to photocopy.

It was also a time of home-made band flyers. The power poles along Parnell Road were wrapped with gig posters made by every available means of reproduction, from linocut to photocopy. That’s right, linocut.

Parnell wasn’t the allegedly desirable residential area it has become. St Stephen’s Avenue was an enclave of the wealthy surrounded by slope of unmaintained rental accommodation owned by uncaring speculators. Most prominent of the homes of Parnell punk was a disintegrating mansion at 27 Birdwood Crescent.

Down a long path in the midst of a huge, impenetrable unmaintained garden jungle, the house had been designed for two spinster sisters of a wealthy family. Each half was a mirror image of the other: four bedrooms on each side, matching fireplaces so impractically large they could be stood in, plus a baronial lounge with double doors between the two sides that could be opened to create a huge party space. Chris Knox announced a Birdwood party from the Windsor Castle stage once. Two hundred people showed up.

Zero, Jimmy Joy and Billy Planet of Suburban Reptiles lived at Birdwood, as did Simon Grigg. So did fringe film director Richard Turner whose feature-length gay movie, Squeeze, managed not only to document Auckland’s 1979 gay scene but also its punk world. Scenes were shot at night on Parnell Road, on Queen Street, and in the Birdwood Crescent house. With music by Toy Love and The Features, it remains a gritty and oddly-accurate record of New Zealand gay punk life.

Punk in its UK manifestation was associated with speed and lager. In New Zealand it was heroin and DB. It was the Mr Asia years. Courtesy of Terry Clark, New Zealand had the highest potency heroin in the West. It suited the nihilism of the music. The great American punk progenitors, Lou Reed and Iggy Pop, had delivered albums that stank of smack and Auckland punk rock took its cue. Sarah Findlay, the daughter of the then Justice minister, was a Windsor regular and would become one of the city’s more notorious smack dealers. But the protection of her father’s name only lasted so long. She would eventually serve prison time and would later die of a overdose in Wellington.

The Globe, Wakefield St, Auckland, 1978, with Sarah Findlay on the left - Photo by Jeremy Templer

And they definitely were overdose years. The potency of the heroin and the fine line between “good time” and “death” meant experimentation could be tricky. Mouth-to-mouth was necessary knowledge. Somebody OD’d and died at Zwines in 1978. He wasn’t the only one. New syringes were impossible to obtain and Hep C was unknowingly transmitted, only to be discovered with the advent of the first available test in the 1990s. Even 30-odd years later, Auckland methadone and Hep C clinics host a number of punk veterans. Old punks never die.

The Windsor Castle eventually called a stop to its Saturdays because of the violence that accompanied the arrival of the boot boys, New Zealand’s skinhead variant. Dancing had really become dangerous. Shaved heads. Tight jeans. Braces. Aggression as an attitude replaced cultural rebellion. Proud Scum would surf the change with their boot boy following. Punk changed to new wave and beyond.

The album AK79 marks and records the transition. Compiled by Bryan Staff, the December 1979 album initially featured The Scavengers, The Swingers, The Primmers, Proud Scum, Toy Love and The Terrorways. It was Auckland punk at the tail-end. The 1993 reissue would supplement the original with Suburban Reptiles, The Spelling Mistakes, The Features, and The Marching Girls, to become the great single document of the time. It’s the sound of Auckland in 1979. You can feel the youthful raw energy. You’re thrashed by the speed-beat. Its big, brash and cocky. You can hear the Windsor Castle on a Saturday afternoon.

Proud Scum's John Atrocity - Photo By Sara Leigh Lewis