Throughout the history of radio there have been songs which, for one reason or another, have been deemed unsuitable for broadcast. There are such memorable cases as the BBC’s banning of Split Enz’s ‘Six Months In A Leaky Boat’ during the naval action of the Falklands War, and the memo issued by the Clear Channel in the US after the Twin Towers attack cautioning against playing such potentially triggering titles as Talking Heads’ ‘Burning Down the House’, Carole King’s ‘I Feel the Earth Move’ and AC/DC’s ‘Safe In New York City’.

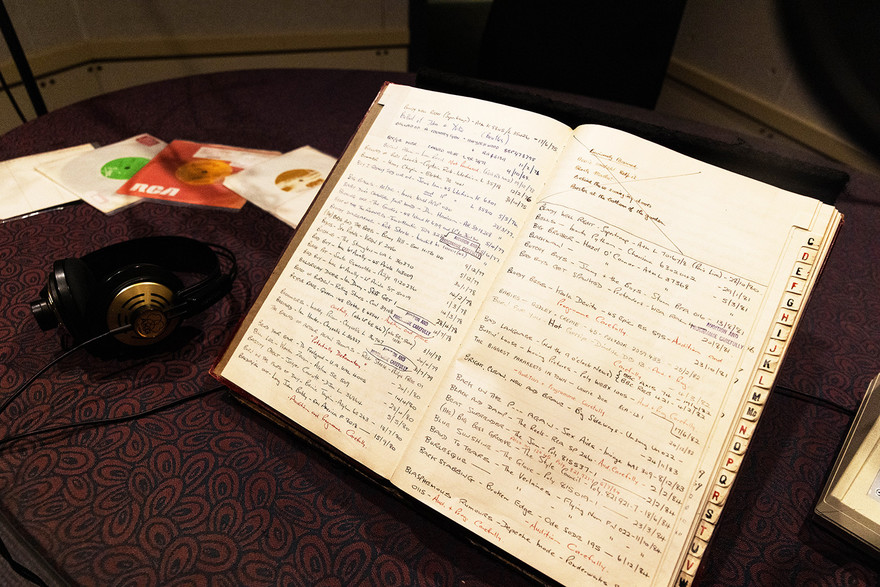

Banned from radio: Broadcasting's ledger of restricted discs, 1952-1988. - RNZ/Samuel Rillstone

When public radio began in Aotearoa in the 1920s, it took its censorship cues largely from the BBC, on which our national broadcasting service was modelled. If the Beeb said a record was offensive, this country usually nodded in agreement.

But what about the records that were produced in New Zealand, some of which might have never even reached British ears? Who would be the judge of these?

Local record production began in 1949. Shortly afterwards, the New Zealand Broadcasting Service (these days known as Radio New Zealand), which controlled almost all radio in the country, established its Purchasing Committee. This group of between four and six employees from the music section of the Wellington Head Office would meet regularly to audition records for airplay. The discs the committee considered acceptable would then be bought from the record companies in multiple units and distributed to the various regional stations; there, they would be played at the discretion of the individual programmers. This process remained in place until 1988 when the fourth Labour government undertook its deregulation of the radio market.

A set of memos from the Purchasing Committee, held in the audiovisual archive Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision, provide some insights into the decisions that were made over nearly four decades.

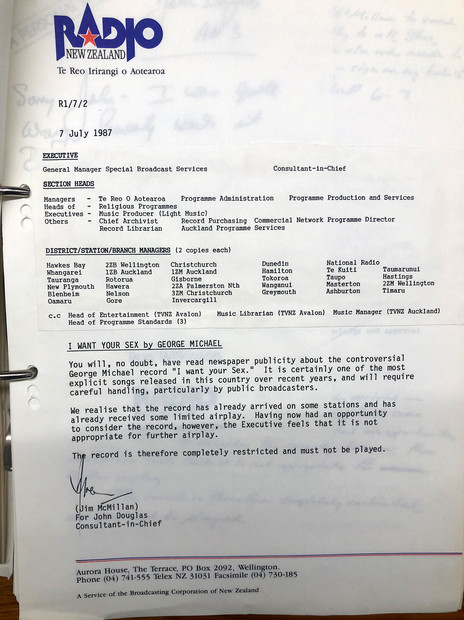

Recalled: George Michael's 'I Want Your Sex', 1987. - Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision

The earliest memos date from 1952. At that time, the main reasons for restricting a record were sexual suggestiveness, depictions of violence, glorification of drugs and alcohol, and the likelihood of causing religious offence. This remained the case through the decades, though thresholds of acceptability changed with the times. In 1954 Judy Canova’s ‘Never Trust A Man’ was banned for being “rowdy, offensive and subversive to the married state”. By 1987, when the Purchasing Committee was anxiously recalling copies of George Michael’s ‘I Want Your Sex’ that had been accidentally sent out to provincial stations, Judy Canova’s disc would hardly have raised an eyebrow.

In the 1950s the Committee was under particular pressure to maintain a strict moral code, particularly when it came to young listeners. The end of the Second World War had seen the emergence of the teenager as a demographic group defined by its own distinct culture and tastes, which were heavily influenced by American movies, comics and music.

In 1954 a series of events, reported in lurid headlines, fed into a public impression that juvenile immorality was on the rise. In June there was the brutal killing by Christchurch teens Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme of Parker’s mother, Honora. The following month the Lower Hutt Magistrates Court heard about “a shocking degree of immoral conduct which spread into sexual orgies” between underage youths of 13 upwards. The court was told these teens would meet in milk bars, where they would arrange their sexual liaisons. Some of the teens rode motorcycles.

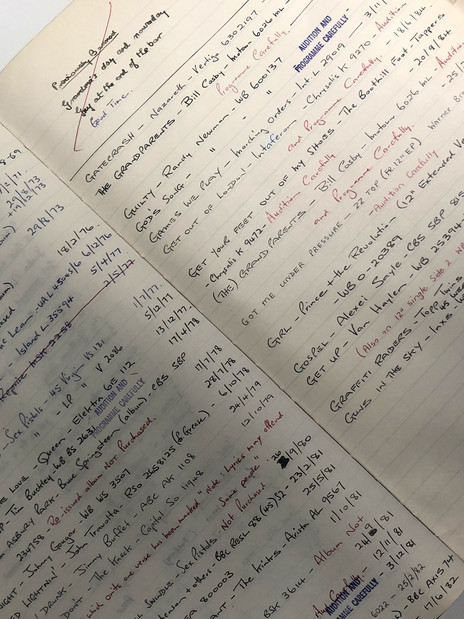

Banned from radio: a sample from the ledger. - RNZ/Samuel Rillstone

As a direct response to the Hutt Valley cases, a special government committee was appointed to look into moral delinquency in children and adolescents, and a copy of their findings was delivered to every New Zealand home. This became known as the Mazengarb Report, after the committee’s chairman Oswald Chettle Mazengarb QC.

Among the report’s recommendations was that the Broadcasting Service should pay particular attention to the type of songs and serials it was playing. “If considered dispassionately by adults, most of these are merely trashy”, the report stated, “but quite possibly, and particularly in times like the present, the words of a song, or the incidents of a serial, may more readily give offence […] Records must first conform with the very strict code of the Broadcasting Service, after which they are classified as suitable for children’s sessions, for general sessions, or only for times when children are assumed not to be listening.”

Peter Downes, RNZ producer, programmer, and National Radio manager. - Photo by Andrew Downes, c. 2019

Peter Downes began his radio career in 1947 and was a programmer at 2YA in Wellington when the Mazengarb Report was published. In a 2008 interview with Chris Bourke he recalled: “The Mazengarb Report thing had terrible repercussions and everybody took it far too far. It gradually found its own level, but it took some years.”

Downes said that even before the report came out “there were indications that there was going to be something like this. The rise of the teenage phenomenon as a consumer, which had never happened before,and the absolute fear […] of this new generation that was just going to the dogs. There was the Cold War and the fact that people had not at that stage got over World War Two by any means. ‘Did I go and fight for King and country for this sort of thing to happen?’”

Hard on the heels of the report came the first strains of the music that would be inextricably linked to this youth uprising. Early rock’n’roll records from America with titles such as ‘Black Denim Trousers and Motorcycle Boots’ (by The Cheers) and ‘Sexy Ways’ (Hank Ballard and the Midnighters) seemed to mirror the incidents that had sparked the Mazengarb Report, and the Purchasing Committee promptly banned them.

But it could be the sound as much as the lyrics that kept records off the airwaves. “Noisy, coarse and crude” was the committee’s verdict on Hank Ballard, while Little Richard’s ‘Tutti Frutti’ was declared a “coarse and ugly performance, words always difficult to hear and often unintelligible”, with the final insult: “Play Pat Boone version only.”

“It’s worth remembering,” says Bourke, “that in the main centres, the ZB stations almost had the field to themselves for the latest pop music. But their audience was extremely broad: they catered for listeners from eight to 80, simultaneously. That didn’t change until the late 1960s, with the arrival of the Hauraki pirates, and then the NZBC responded with the ZMs.”

The first local records documented in the memos appear to have been restricted for purely technical reasons. In October 1955 a song titled ‘My Romance Has Ended’ was deemed unsuitable, but not because of any suggestion that the romance in question might have involved orgies or ended in the Magistrates Court. Rather, the committee stated: “This is a composition submitted by a local composer who had it recorded at his own expense. The recording is technically poor and the performance unacceptable.”

As for ‘Please Don’t Take Him Away’ by Otago country and western group Cole Wilson and the Tumbleweeds – a mother’s plea, sung from the bedside of a dying child – the song was simply considered too maudlin for the public good. Similarly, ‘The Mother of a Honky Tonk Girl’ – a cover of a Jim Reeves song released by Les Wilson, Cole’s younger brother – was banned in 1959, presumably because of its descriptions of a young woman whose life is in disarray.

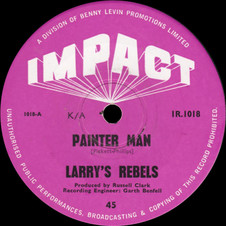

Banned from radio: Larry's Rebels - Painter Man (Impact, 1967)

Once the fear that rock’n’roll was feeding a youth revolt had receded, other reasons arose for restricting local records. By 1967 Larry’s Rebels were one of the country’s most popular bands. Their music was a perfect fit for pop programmes like The Sunset Show that had become a feature of the NZBC’s commercial stations. But after an initial burst of airplay, their 1967 hit ‘Painter Man’ was suddenly withdrawn, following a complaint from a listener who identified references in the song to “dirty postcards” and claimed to have heard the words “shit can” (the actual lyric is “tin can”). This was the first public victory of morals crusader Patricia Bartlett, who would go on in the decades that followed to become the country’s most prominent censorship advocate. In 1968, Fourmyula’s ‘Mr Whippy’, off their debut album, was banned, presumably because of product placement.

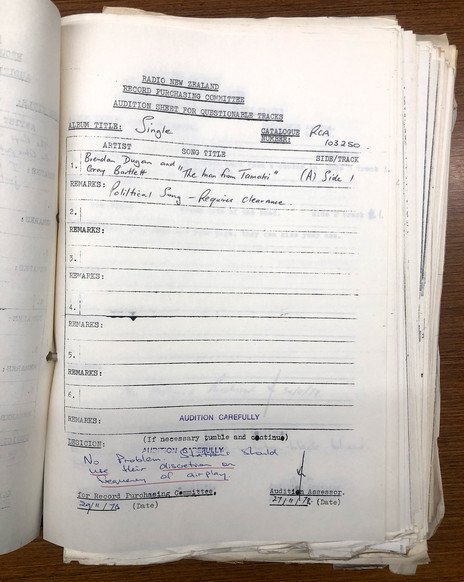

Not banned from radio: Brendan Dugan and Gray Bartlett. - Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision

Political songs posed another question for the Purchasing Committee. Should a song such as Brendan Dugan and Gray Bartlett’s 1975 ‘The Ballad of Robbie Muldoon’ be regarded as an election advertisement? Though the Johnny Cash-style country ballad presented the National Party leader as a kind of outlaw hero, it was decided that the record’s release was far enough out from that year’s general election that it would not be mistaken for a campaign song and it was green-lit for airplay.

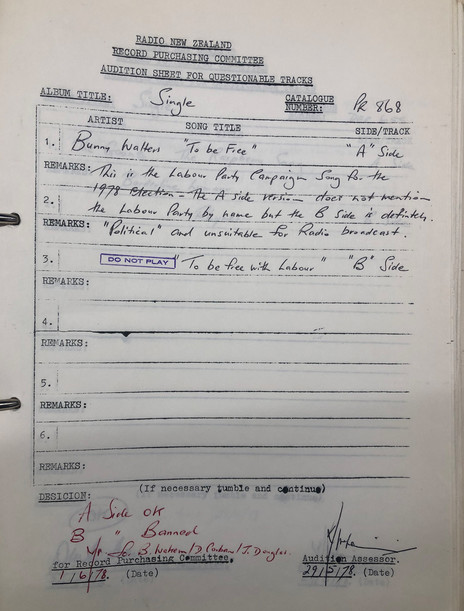

Banned from radio: Bunny Walters. - Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision

Three years later, with another election looming, Bunny Walters released ‘Born To Be Free’, a song that looked back nostalgically on the days before Muldoon’s government. While the song had in fact been commissioned by the Labour Party, the record was nevertheless approved – at least the A side was – as it does not mention the party by name. But the B-side, though almost exactly the same song, spelt its message out more bluntly – “To Be Free with Labour” – and would not be broadcast.

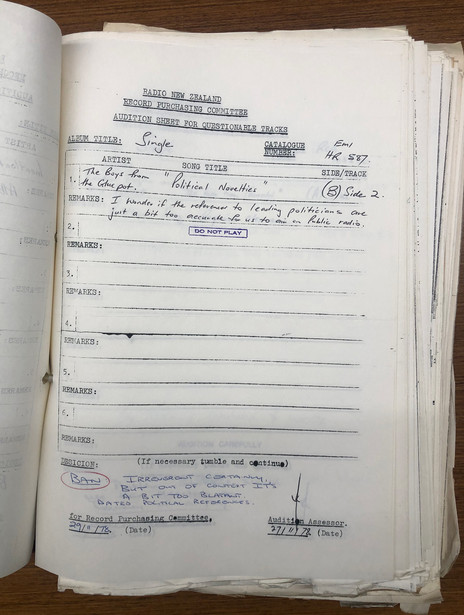

Banned from radio: Political Novelties, by The Boys From The Gluepot. - Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision

Nor would a song called ‘Political Novelties’, released that same year by a trio calling themselves The Boys From the Gluepot – actually satirists David McPhail, Jon Gadsby and Chris McVeigh from the satirical television series A Week Of It. The verdict was that “the references to leading politicians are just a bit too accurate for us to air on public radio”. But a new song in praise of Muldoon from Dugan and Bartlett, ‘The Man From Tamaki’, was marked “No problem,” though stations were asked to “use their discretion on frequency of airplay”.

(By the time Hutt Delta bluesman Darren Watson released his political parody ‘Planet Key’ in 2014, an election year, the decision on whether or not it constituted an election advertisement was no longer up to the broadcaster but was instead determined by the Electoral Commission, who imposed a ban on the song. Watson appealed to the High Court who found in his favour, however by the time their judgment was released the election was over.)

Right Left and Centre was an all-star cast of New Zealand musicians - their single 'Don't Go' implored the All Blacks not to tour South Africa in 1985. Among the singers were Rick Bryant, Don McGlashan and Chris Knox

After the divisive Springbok tour of 1981, a proposed 1985 All Black tour of South Africa was met with a musical protest from a group of singers and songwriters calling themselves Right, Left & Centre. Don McGlashan, Chris Knox and Rick Bryant led the chorus of ‘Don’t Go’, a Soweto-inspired anthem written by McGlashan, Geoff Chapple and Frank Stark.

The week of the record’s release, a memo was sent to all district and regional managers of Radio New Zealand’s commercial stations from Controller of Programmes John Douglas:

We have decided not to ban the record outright, as it could be regarded as legitimate social comment. The record is therefore being supplied to you to be played at your own discretion.

However we would ask to keep a personal eye on the use of this disc, and these points should be noted:

1) We would not expect the record to reach playlist rotations. Obviously if we were to play the record several times a day we would be seen to be editorialising.

2) The record should not be played into or out of news bulletins or in current affairs programmes where it could upset the balance of our coverage.

3) Jocks should not make any political comments in association with the song.

Six weeks after ‘Don’t Go’ the same regional managers received another record, this one pro-tour. ‘Let Them Go’ was credited to The Silent Majority. Though the musicians involved maintained a strict anonymity, it appears the song was composed by Hoghton Hughes, self-described “mass-market marvel”, whose record label Music World was omnipresent in the 1970s and 80s, supplying such outlets as dairies and petrol stations with soundalike compilations, Christian music, bawdy ballads, yodellers – essentially anything he thought he could sell, all at a budget price.

Johnny Douglas (back row, white hair), long-serving NZBC and RNZ music programmer, with the Gremlins and Peter Sinclair (front right).

Accompanying the copies of ‘Let Them Go’ was another memo from Douglas:

You will have received in this week’s new records song which replies to the previous anti-tour song ‘Don’t Go’ – this one is ‘Let Them Go’ by The Silent Majority. This record does have the virtue of providing some balance on this subject. However the musical quality of this disc is really quite appalling, and we would frankly be surprised if stations were to give any substantial airplay to either of these tour songs.

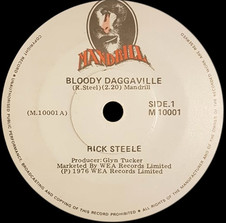

Rick Steele - Bloody Daggaville (1976, Mandrill)

The Purchasing Committee evidently found some decisions easier than others. Take It Or Leave It was the title of Rick Steele’s 1977 album. Confronted with songs like ‘Bloody Daggaville’ (“every second word a swear word”, a committee member noted), rhymes like “smoking grass/kiss my ass”, and songs such as ‘Jenny Lee’ that seemed to promote sexual violence, they had no hesitation in leaving it. In 1980, the committee banned Steele’s ‘The Ballad of Arthur Allan Thomas’ becuase it was “potentially defamatory”.

A 1983 album, Prince Tui Teka Live In New Zealand, was marked “contains material which may be unsuitable”, noting that “various jokes could offend people” including patter about “transplants and dropping his trousers”, though the aside “aw shut up”, muttered during the song ‘We Three’, was deemed to be “OK”.

Actor and comic Beryl Te Wiata was another whose humour was deemed liable to offend. Her sketch ‘The Doctor’s Waiting Room’ from the 1981 Mrs Kiwi Arthur Presents album was singled out for including the phrase “poor little bugger” and what the committee referred to as “some unsavoury portions of medicine”.

Punk and post-punk music presented the committee with some new issues, as well as some old ones. The Clean’s Oddities cassette was rejected because of references to alcohol and drugs, with such offending lines as “sit all day and drink piss at the pub” (‘Hold Onto The Rail’) and “Who’s gonna take your pills today?” (‘Thumbs Off’).

The EP New by Naked Spots Dance was cautiously accepted, but with a warning to programmers that the title song – a commentary on colonialism – contains the phrase “syphilis and disease”. The verdict: “Programme carefully.”

The Topp Twins’ ‘Graffiti Raiders’ might have got away with being what the committee coyly described as a “song protesting restrictions placed on us” (it is essentially a celebration of tagging) but for the phrase “a lot of s---”.

The Tin Syndrome’s ‘American Blessing’ was banned for the line “But for you I wouldn’t give a f---” near the start of the song. Though it was admitted in the memo that the line is barely audible, the committee had been alerted to it by the lyric sheet – which might be an argument against including lyric sheets if you want your record played.

Banned from radio: The Verlaines' 'Baud To Tears', 'Joed Out', 'Burlesque'. - Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision

The F-word was identified as being “very clear” in The Verlaines’ ‘Joed Out’, from the 10 O’Clock In The Afternoon EP, which was banned along with two other tracks: ‘Baud To Tears’ (“he hasn’t got a s--- show … with a head full of crap”) and ‘Burlesque’, which was noted to be a “protest song” and “could be blasphemous”.

Someone thought they heard Jenny Morris sing “feel so f---ing blue” towards the end of her 1982 solo single ‘Adolescent Angst’ (released as The Morris Majors), but as it was “not clear” and “probably not even these words” the song was passed, though it failed to get much airplay anyway. Jenny would have her first solo hits later in the decade.

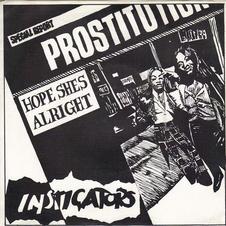

Instigators - Hope She's Alright (Ripper, 1982)

The committee heard the F-word again (and “a possible s---”) in the Instigators’ 1982 single ‘Hope She’s Alright’, enough to keep it off the air. But a further note – “song about prostitution” – suggests that the record might have been banned anyway.

Sometimes ambiguity worked in the artist’s favour. “Drug song?” asked a committee member auditioning Daggy and the Dickheads’ ‘Talk Turkey’ (1982), pointing to the lines “No fun if you’re not sedated” and “C’mon man, won’t you give it away?” “Might be!! Might not be!!” was as much as the colleagues could conclude, and no action was taken.

The committee would carry on selecting or rejecting records in this manner until 1988 when the BCNZ was dismantled. In its wake, private commercial stations and commercial radio networks sprang up. How would this effect the moral landscape of the nation’s airwaves? On 27 September 1988 the acting assistant director-general of Broadcasting, John Craig, sent all remaining branch managers a letter in which he noted – with a hint of trepidation and a touch of poetry – the passing of an era.

As you know, the long-established procedure of a Head Office committee, auditioning, accepting or restricting recordings, came to an end at August 31 this year.

Now the work of the Head Office Audition Committee has devolved to become the task and responsibility of individual stations.

I believe it is both necessary and appropriate that managers develop some guideline framework to apply and to keep under review for those of their staff who will now perform the assessment of recordings for on-air acceptability and relevance. Most of our traditional attitudes have been based on the sagacity and experience of a central group whose sensitivities were tuned by consent exposure to the changing, evolving (some say eroding) mores of the day. Now the bases of their judgement have been diffused to the user groups. I hope you can appreciate that my concern for the retention of consistency of attitudes, if not detail, is prompted more by our continuing need to comply with the strictures of statutory requirements, and the eventual Standards Authority, than the nervous paranoia of a reluctant liberal.

Some things will not change unless society as a whole demands the change. Lyrics which lean on or promote such subjects as:

drug taking

incest

rape

suicide

the graffiti on the toilet wall

the expletives of the bar-room brawl

should have little place in the broad-based entertainment principles of the target audience we seek to please.

Please treat the subject seriously and try to ensure that those of your staff to whom you delegate such tasks have a clear understanding between the difference between freedom and license.

J Craig

Acting Assistant Director-General – Operations

--

New Zealand songs banned by New Zealand radio – a selection

Nick Bollinger has produced a radio series on this topic, as well as an accompanying article on the RNZ website, Not For Broadcast: the Story of New Zealand’s Censored Songs.

--

Read more: Banned! Ten videos and songs “with issues”