Peter Allison played keyboards for The Chills from 1983 to 1986. He wrote this story for Metro in 1988.

--

Martin John James Phillipps was born in Wellington on 2 July 1963, the second of Donald and Barbara Phillipps’ three children. The call of Reverend Phillipps’ ministry took the family to a parish at Milton, 60 km south of Dunedin, then in 1970 to Dunedin, where he became university chaplain, then superintendent of the Dunedin Methodist Mission.

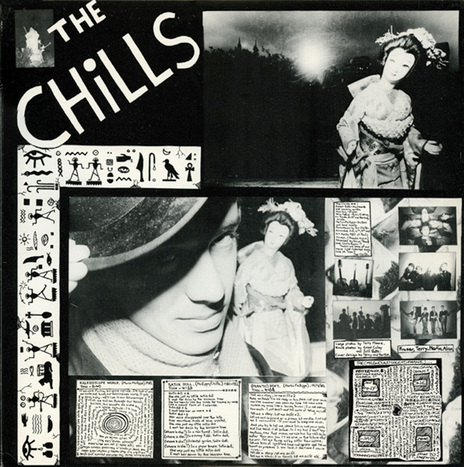

The Chills, 1985: Alan Haig, Peter Allison, Terry Moore, Martin Phillipps. - Shake! collection

The young Martin grew up in a musical family – his mother played the cello and his father sang in choral groups. Later, when his voice broke, it would become clear that he had inherited something of his father’s fine baritone. But Martin “rebelled” against the few formal music lessons he had (recorder for a term, piano for a year). First, other things were capturing his imagination.

There was drama – his older sister Sara remembers him stealing the show at a Bible class production as a “ridiculous, villainous character, like the Joker from Batman,” and reading – he liked fantasy fiction by C S Lewis and Tolkien, inheriting his father’s passion for The Lord of the Rings, and science fiction, particularly Ray Bradbury. Bradbury’s stories would later provide the inspiration for songs such as ‘Dan Destiny and the Silver Dawn’ and ‘Kaleidoscope World’.

His love of the fantastic shows up again in his extensive comic collection especially 2000 A.D. and The Phantom and his interest in 60s TV shows like Thunderbirds and Captain Scarlet.

And in his artwork. He showed an attention to detail – his parents recall lots of fine work, not big brushstrokes – and an interest in the surrealistic. “At high school the art teacher was horrified when Martin drew this forest with arms and legs and things,” says Barbara Phillipps. (Later he would design his band’s record covers in his naive, comic-book style.)

Young Martin was a dreamer. For a long time he wanted to be a shark hunter, then an astronaut. “I was always into escapism – I would’ve been honestly about 12 or 13 before I realised that I wasn’t going to get away from this planet. I had one of those green army-surplus jackets and I’d always have a pocket knife and matches in the pockets, waiting for when I was going to get zapped up. The sentiment formed the basis for his song ‘The Great Escape’.”

Later, his first girlfriend Jayne Patton (later Jayne Page) would notice that dreamy streak in him. When they were alone they’d drive in his parents’ old maroon Peugeot 404 down to the local gardens, to the harbour or up the hill above Ōpoho to a lookout over the city. Or to Lovers’ Leap on the Otago Peninsula, a traditional lovers’ haunt where a sheer cliff drops away to the rocks and the pounding surf hundreds of feet below.

“He was a romantic, I guess ... he seemed more intrigued with the stars and UFOs and things” – Jayne Patton

“He was a romantic I guess,” says Patton, “but he seemed more intrigued with the stars and UFOs and things. He was a quiet, sensitive person who never really said what he felt – maybe he could never really express himself except in his songs.”

Songs like ‘Rolling Moon’, ‘Oncoming Day’, and ‘Night of Chill Blue’ reveal the inspiration Martin drew from those wild landscapes and starry nights. Even the lights of the city contributed to the Phillipps mythology: the ‘Green-Eyed Owl’ was his interpretation of the green neon clock on Arthur Barnett’s department store, at 10 minutes to two.

And there were times spent experimenting with alcohol and drugs; there’s no doubt that kaleidoscope world inside his head grew from nights spent, both geographically and imaginatively, at the very edge of the world.

Somewhere down the line someone gave him the nickname “Martian Flips”. It seemed to fit this strange young man with an imagination not quite of this world.

Roy’s kaleidoscopic world

One day he discovered rock music. “I saw the film clip to [David Bowie’s] ‘Jean Genie’ and I’m sure that was the moment I got turned on to rock music. I was over the moon, dancing around the kitchen at my grandparents’ pretending to play guitar, absolutely enthralled ...”

Dunedin, midwinter, is not the most hospitable place for an early morning outdoor job, but he risked getting mild hypothermia a few times to do a paper run for seven dollars a week, enabling him to pay for the expensive habit he was cultivating: collecting records.

“The first record I bought was Rock Explosion because it had The Sweet on it. I started buying seriously one day when I went to the shop and bought Ziggy Stardust and Queen’s A Night At The Opera. About a week later I walked into Roy Colbert’s shop and discovered second-hand records.”

Roy Colbert at Records Records, Dunedin.

Roy Colbert. Mild-mannered record shop owner by day; by night, a champion for Dunedin music.

As the only shop specialising exclusively in second-hand records, Roy Colbert’s was a mecca for every budding musician in town. The ever-modest Colbert would never admit it, but he probably had more input into the development of the Dunedin sound than many people realise: by steering the young hopefuls in the direction of music they might not otherwise have heard – chiefly towards the “Obscure 60s” and “Psychedelic” bins.

But more than that, Colbert – a witty and articulate writer who for years filled most of the sports and entertainment pages of Dunedin’s Evening Star – would fire out enthusiastic reviews of Dunedin bands for Rip It Up and the Listener, and later write the sleeve notes for the Chills’ Kaleidoscope World and Flying Nun’s Tuatara compilation albums in the style of a true 60s raver.

When Martin discovered Roy Colbert’s shop, he went in and bought two Bowie records for $4 each. “I never looked back. I just started buying heaps and heaps of records.”

That was in 1976. Now he has at least 1100 singles and 800 albums, an eclectic collection culled from everywhere, from small-town junk shop singles bins to obscure import catalogues: a huge variety of sounds to fill his head.

The old Same story

At age 13, Martin got his first guitar (“a really cheap plain acoustic”). He had very few formal lessons but spent hours in his bedroom trying to teach himself David Bowie and Lou Reed songs. “Even then I was trying to play ‘Sweet Jane’ on one finger ...” Soon, he moved on to electric: a Diplomat copy of a Gibson SG, then his trademark blue Fender Coronado II semi-acoustic.

One day in the playground at Logan Park High School, a guy named Jeff Batts sidled up to him and said, in his slow, bored voice, “I hear you’ve got an electric guitar.”

Over Labour Weekend 1978 Batts and Phillipps stayed up all night with their friends Craig Easton and Alistair Dunn bashing away at their instruments (Dunn on biscuit tins). That was the birth of schoolpunk band The Same.

A slightly revised line-up played covers of ‘Wild Thing’ and ‘Louie Louie’ and moved on to some “fairly out-of-control punkish originals”. For a long time, the band’s magnum opus was ‘Thalidomide Baby’ – a ballad-cum-punk thrash in the worst possible taste. But among the chaos were softer Phillipps contributions such as ‘Frantic Drift’ and ‘Kaleidoscope World’.

They played with The Clean and Bored Games at suburban halls, concerts organised by the bands themselves: “There was absolutely nothing for us to do as teenagers so we created our own entertainment,” says bass player Jane Dodd. “It was great fun but they were always fraught with trouble. There’d be fights – quite often with surfies or other people who weren’t involved with the bands – and the gigs would be closed down.” They played live on Telethon at seven in the morning. And they even played with Toy Love.

One version of Martin Phillipps' early band The Same (L-R): Paul Baird, Martin Phillipps, Craig Easton, Jane Dodd, Rachel Phillipps

In early 1980, Martin’s idols Toy Love had come to town to play at the Captain Cook Tavern, and Martin, then 16, set up half-a-dozen deckchairs outside the packed pub so he and his friends, all underage, could enjoy the night as much as possible without risking going inside.

Rock writer John Dix, author of the definitive history of New Zealand rock’n’roll, Stranded In Paradise, tagged along for Toy Love’s swansong tour six months later. He remembers staying at the “grubby old bandhouse” next door to the Cook, and the young Martin Phillipps coming along straight from school with his schoolbag and short pants. “He introduced himself to Chris [Knox] and said ‘I’m from The Same’. The next day he came back and asked if The Same could play with Toy Love, and the day after and the day after that.”

Eventually Toy Love gave in, and The Same – by now Phillipps (guitar/vocals), his sister Rachel (guitar), Jane Dodd (bass) and Paul Baird (drums) – played a short Saturday afternoon set before their heroes.

A stubborn little bastard

Martin’s teachers remember him as a serious kid, helpful, cooperative, well-behaved, with a flair for words and art. But he wasn’t particularly interested in schoolwork. He was bright enough, but his mind was wandering and when it came to School Certificate, he managed to get a good mark in English and Science, despite the fact that he’d been to the Bowie concert in Christchurch the night before. But he missed everything else.

One or two incidents marked him out from the common herd. There was a tin of printers’ ink. (“I had to open this large tin of blue ink, and I couldn’t resist putting my hands in, right down to the bottom. The art teacher went off the edge.”) There was the time he came to school with his head almost shaved bald – Logan Park’s first skinhead. It wasn’t his idea: the hairdresser had got a bit carried away.

In a biology exam he had “no idea” so instead wrote a psychedelic essay. Some of it ended up in ‘Rolling Moon’

Then, in a mid-year biology exam he had “absolutely no idea” so instead he wrote a psychedelic essay. “Emerald green dreamstone falls softly into a pool of lime beneath the silver boughs, firebirds flying over mountains, lone pipers.” That sort of thing. Some of it ended up in ‘Rolling Moon’.

It nearly got him expelled: “They couldn’t work out why I’d bothered coming back,” says Martin. Jayne Patton recalls: “By then he had given up on school. He just wanted to be a musician, and not just a musician, a bloody good one.”

“I basically blew the end of my education for music,” says Martin, “which I regret to some extent, because I really value education and I do see it as the answer to a lot of the world’s problems. But I blew it because I knew they were trying to shape me into a working unit. Career advisors would say to me, ‘Why don’t you just keep your music to the weekends?’

“If I’d been a virtuoso violinist they probably would’ve encouraged me to go to music school. I had nothing to show them apart from really rough punk rock, so of course they couldn’t see the depth behind it. But they should follow people’s dreams a bit more, hear them out. Often these really basic talents just get squashed in people. I saw some potentially good artists at school just go down the tubes and end up as accountants. You’ve got to be a stubborn little bastard to get through the system with any drive to go and do your own thing.”

He finished Logan Park with three subjects in School Cert. A decade down the track, that doesn’t seem to matter in the slightest.

The birth of The Chills

The Same had run its course. Martin started jamming with Peter Gutteridge (bassist from the original Clean line-up) and drummer Alan Haig. He asked Jane Dodd to join, Rachel switched to keyboards, and sometime in October 1980 The Chills were born.

So the original Chills was connected to The Same by three members and three songs: ‘Frantic Drift’, ‘Kaleidoscope World’ and ‘Satin Doll’ (not the Duke Ellington standard). At the time, says Martin, from The Same to The Chills seemed like a big break. But later changes would be much more dramatic.

The five-piece line-up thrashed around in the Phillipps’ garage, much to the chagrin of the neighbours, learning a Marty Wilde song ‘Endless Sleep’ and some of Martin’s songs: ‘Kaleidoscope World’, ‘Frantic Drift’. ‘Motels and Cars’ (a put-down of American “new wave” bands the Motels and the Cars), and ‘I Saw Your Silhouette’.

And soon he’d write the forgotten gem “The Chills’ Song” which had priceless lyrics like: “Relate to us and you relate to a fridge / We’re the coldest band in town but above averidge / We’re the Chills!” and “... Emotion, illusion, simplicity – The Chills.”

Before their first gig they needed a name. Martin: “I think I was sitting by the window at home. It was quite cold. I thought about ‘Draught’, then ‘Chills’. I liked it because of that idea of getting a shiver down your spine when you’re watching a band and things really take off.”

The Chills’ debut was an impromptu one on 15 November 1980, at a Bored Games and Clean gig at Coronation Hall in Māori Hill. The band got up and played a couple of songs without Rachel, who had no keyboards yet. A tape of the event reveals a very rough sound featuring a guitar amp which kept cutting out – the first of many Chills gremlins in the works.

Martin Phillipps returns to Coronation Hall, Dunedin, 2017 - Darryl Stack/RNZ

Flying Nun takes off

Meanwhile in Christchurch, young record store employee Roger Shepherd noticed there was some good music happening around Christchurch and Dunedin and had the idea of setting up a small record label similar to Propeller in Auckland “from the point of view of preserving some of the music that was happening rather than selling bulk.” The result was Flying Nun, a record company that took flight on little more than a wing and a prayer but is now the country’s most internationally successful independent label.

The first two singles recorded by Flying Nun were The Pin Group’s single ‘Ambivalence’ and The Clean’s ‘Tally Ho’ – recorded for $50, with special guest Martin Phillipps on keyboards.

Less than a year later The Chills, already plagued by departures and onto its third line-up, recorded three songs for the historic Dunedin Double 12" EP on a four-track tape recorder in primitive conditions in the lounge of a Christchurch house, with Chris Knox and Doug Hood at the controls.

The Chills' side of the Dunedin Double 12" EP (1982)

Hood remembers being “absolutely knocked over by ‘Kaleidoscope World’ – it was the one that made you think, boy, there’s really something special happening here.”

Martin: “We thought we had a definite radio hit with ‘Kaleidoscope World’, so I sang self-consciously and sweetly, and when we came to mix it, we put the vocals way up.” The commercial radio stations would completely ignore it, as they would completely ignore virtually all the Flying Nun recordings. But the critics saw it as a promising start. The music was great, they said. And as for those lyrics …

Roy Colbert in the Listener: “Well, who really knows where they come from? ‘I can’t believe he could possibly have experienced all this,’ mused Chris Knox, as he ran his eye down the word sheets during the recording of Dunedin Double EP. True.”

Rolling moons

Apart from the line-up changes – people leaving for work, education, or travel reasons – and the equipment hassles which happened with monotonous regularity, things were rolling along quite nicely. They’d played Christchurch several times and were now on their first trip to Auckland to play with The Clean. They scraped together a deposit for a $6500 mustard-coloured CF Bedford van. It appeared sound, but it soon became obvious that like the rest of the Chills equipment, it too would be cursed with frequent breakdowns. But they were blessed with good gigs at the Rumba Bar and Reverb Room and more magic in the recordings of singles ‘Rolling Moon’ and ‘Pink Frost’.

The critics were taken with the jangling guitars and the “irresistible keyboard riff that just has to be whistled”. “Honestly,” one wrote, “this record is so good you cannot afford not to buy it. ‘Rolling Moon’ is the best New Zealand single since ‘Don’t Ask Me’ by Toy Love.”

And in the Listener in December 1982 Roy Colbert (again) described ‘Rolling Moon’ as “a record that should be poking from the top of every Christmas stocking ... an irresistible slice of pop that bounces from the speakers with a grin from ear to ear.”

--

An edited excerpt from Peter Allison’s article “The Curse of the Chills”, which first appeared in Metro, November 1988, and is republished here thanks to Peter Allison.