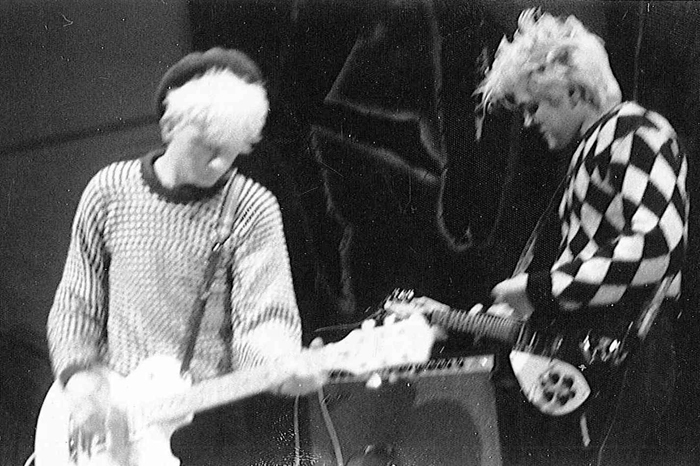

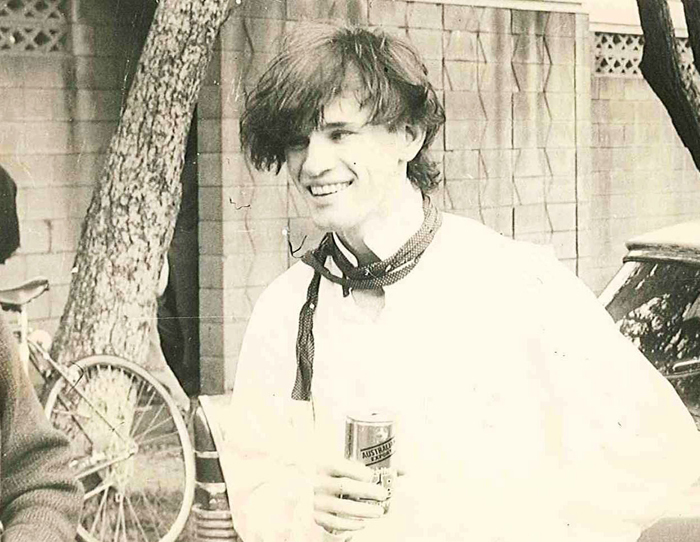

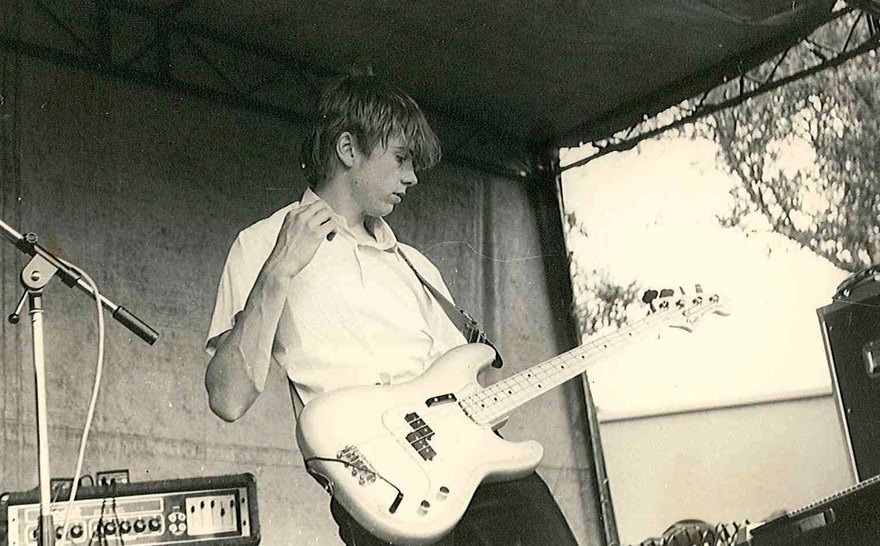

The Screaming Meemees at Sweetwaters, January 1983 - Photo by Jonathan Ganley

It was the best of times and yet it came very, very close to being the worst of times. It was December 1982 and Jim Wilson had rung me. “Bring the Meemees down to Christchurch for three nights at the Hillsborough,” he invited.

Each successive trip had seen bigger queues and a jump from the smaller Gladstone to the bigger Hillsborough made it increasingly worthwhile.

It was tempting for a number of reasons: The Screaming Meemees had always done very well in the Garden City with capacity crowds each time since that first trip to the city as part of the Class Of 81 party at The Gladstone in April 1981. Each successive trip had seen bigger queues and a jump from the smaller Gladstone to the bigger Hillsborough made it increasingly worthwhile. The band had sold more albums and singles in Christchurch than anywhere else outside Auckland. Plus Jim Wilson, who ran the Christchurch scene, was probably the nation’s best promoter, with a firm finger on the public pulse.

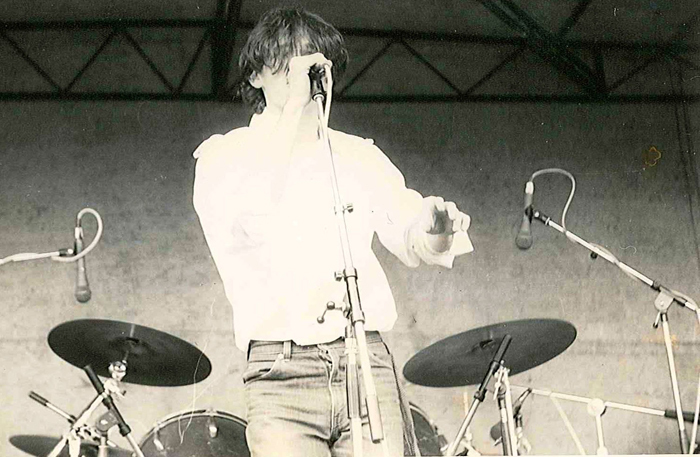

The Screaming Meemees, Chateau Tongariro, August 1982 - Photo by Murray Cammick

“It’s time to come back,” assured Jim, as he offered a hefty guarantee. That in itself was tempting, as the band desperately needed the cash – hire purchase payments on a van, guitar and drum kit, plus two waged employees, Tom and Terry, were a steady drain.

However the budget, despite the guarantee, which Jim increased twice, was still tight. Airfares for eight on Air New Zealand, with its hefty monopoly, threatened to gobble up a large part of the budget therefore making the trip financially pointless.

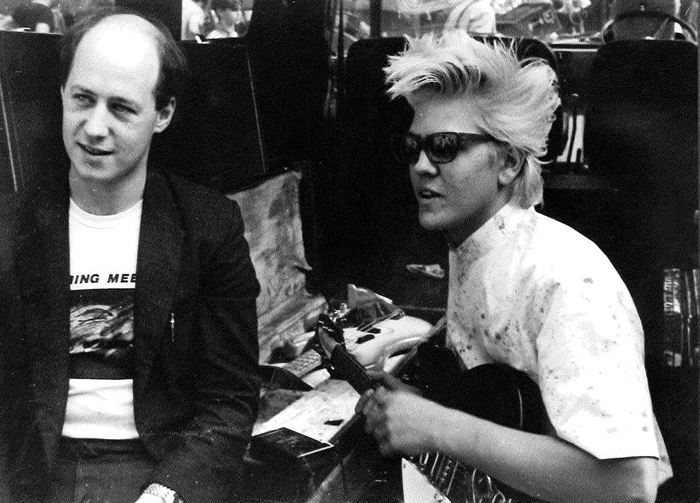

Adam Holt and Mike O'Neill, venue unknown, 1982 - Photo by Jim Abbott

The band too, was in an odd space. The album, If This Is Paradise I’ll Take The Bag, was released to good sales (and excellent reviews, not only in New Zealand but in Australia and the USA, where hipster mags Trouser Press and Bomp had both raved about it) but there was an inevitable sense of deflation and “where to now?” that followed the highs. The band was disinterested in touring New Zealand yet again and had reached a point where substantive change was needed if they were to carry on.

Steve Anderton, who guested with The Screaming Meemees on brass, and Tony Drumm, Chateau Tongariro, August 1982 - Photo by Murray Cammick

The initial answer to the question was a new single in a new studio. ‘Stars In My Eyes’ was the first recording The Screaming Meemees had done away from Harlequin Studio. Glyn Tucker’s Mandrill Studio revitalised the recording progress and as much as Paradise was a quantum leap from the earlier singles, Stars was a stylistic and adventurous bound much further. The once ska-punk band dropped much of its repertoire, including hits like ‘See Me Go’, replacing the songs live with brand new compositions or radical reworkings of early tunes, that emphasised the sort of punk-funk rhythm that drove ‘Stars’.

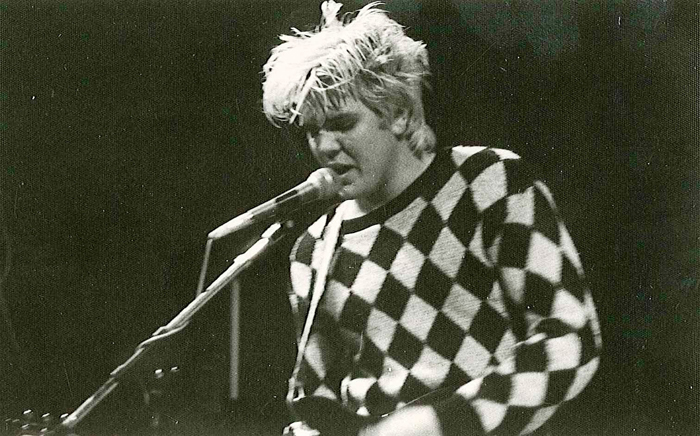

Michael O'Neill, Devonport Domain, summer 1982 - Photo by Jim Abbott

And they were all still under 20, and growing up, which meant that relationships were changing, and in one case fracturing. The band, too, was trying work out whether they wanted to go overseas – which required a rather bigger commitment to the band than the current lifestyle of four young men having a good time as local stars in New Zealand.

Yoh, Devonport Domain, summer 1982 - Photo by Jim Abbott

But in the interim they still needed money to pay the bills. The cost of getting to the southern city was making the Christchurch trip increasingly unlikely. That is, until Tony made a suggestion: we could fly down in Cessnas. The offered plan was that we could hire a couple of planes from the aero club at Auckland’s Ardmore airfield in a sweet deal arranged by Hilary. Hilary was Hilary Hunt, an early member of the band (he would later sing in The Ainsworths) and their first informal manager. He was learning to fly at the club. We could send the drum kit via Air New Zealand and pick up other gear down there.

Peter van der Fluit, Devonport Domain, summer 1982 - Photo by Jim Abbott

It was an insane idea but the adventure – and insanity of it all if I’m honest – appealed and at our regular Monday afternoon band meeting it was agreed. It seemed like an adventure to us all, or at least to most of us. The road crew were less than supportive but the band had decided. Paid employees got to voice an opinion but didn’t get a vote. In retrospect we should have listened to them.

Tony Drumm, backstage at Devonport Domain, summer 1982

I told myself planes like these flew up and down the country every day and only a very few were lost.

Three weeks later we found ourselves standing on an early morning airfield in South Auckland. The two pilots were experienced instructors and Hilary would co-pilot one plane. We would be split between the two single engined planes. Standing there, they were smaller than I had imagined, more like a Corolla with wings. And far flimsier. I told myself planes like these flew up and down the country every day and only a very few were lost. A very few.

The weather was good and we lifted off into a clear blue sky in high spirits. The only question nobody seemed able to answer was how long this would take. The answer was “depends …” On what, I had no idea.

Michael O'Neill and Tony Drumm, Chateau Tongariro, August 1982 - Photo by Murray Cammick

As we trundled along at a low altitude I was quite enjoying the flight. I think we all were, even the previously reluctant road crew. The day was stunning and the scenery below was expansive as we flew down the Waikato then Taranaki coasts. I was taken aback at how densely bushed and rugged so much of our sparsely populated nation is, and the company was good. We could see the other plane some 200 metres or so to our starboard, bumbling along as we were. That answered part of the “how long” question – it would take clearly a wee while to get to Christchurch. These things, with their gnawing piston engines, were not speed demons. Initially, we were told, we were heading for the beachside aerodrome at Paraparaumu, just north of Wellington, where we would refuel, bathroom and eat.

Then the weather turned from blue to ominous and the horizon went from expansive to claustrophobic within minutes. Grey clouds seem to fall on us over the Rangitikei and our tiny metal airborne box started bumping and rolling. It seemed smaller than it was just a few minutes back and we’d lost visual contact with the other plane. The pilot, a cheery redheaded guy, and Hilary, who was next to him, both assured us it was fine and wouldn’t last.

It got worse and it began to rain. As we were tossed up and down and side to side our stomachs – we’d begun the day with band-standard pies – worked against the pitching and began to churn. I was okay but one of the road crew – Terry I think – found that he could slide the window open, and he threw up out of it. Somebody else followed. I was just grabbing my seat and we were all grimly pale – sick and absolutely terrified. All except Hils and the pilot. “It’s a wee bit rocky but not too bad,” Hils smiled. Whether it was the lack of available words to express or the nausea, I don’t know, but there wasn’t a reply. There was moaning. Terry was still throwing up.

Tony Drumm, Devonport Domain, summer 1982 - Photo by Jim Abbott

Someone was throwing up as the rest of us assured ourselves the worst was over.

Paraparaumu appeared and I bent my fingers away from the seat I’d almost clenched them through. As we landed, some four-and-a-half hours after we’d left the now distant security of Ardmore, we saw the other plane parked outside the local aero club and we taxied over, openly thanking any available deities for the deliverance.

The others stood there smiling, wolfing down more pies. They’d peacefully toddled down the lower part of the North Island some 40km to the east of us and had missed the storm completely. The smell of their steak and cheese pies didn’t help our mood and we all declined food. Someone was throwing up as the rest of us assured ourselves the worst was over.

We fuelled and wee-wee-ed and then took off again. I for one was looking forward to seeing the Southern hills and Alps from the air as we headed south along the Kaikoura coast, as promised by the pilot. However, as we passed over Cook Strait we noted ominous big grey clouds ahead. It seemed we were catching up to the storm again. The plane was silent aside from the ever-present drone of the Continental piston motor. The radio crackled and the pilot had a conversation with someone on the ground somewhere. It seemed that a yacht had gone missing off the northeast coast of the South Island and we’d been drafted in to search for it. It was, he cheerily explained, compulsory for us to participate in any such search. Plus it was the decent thing to do. The other Cessna had had the same call and for the next hour-and-a-half both planes went around and around and looked for a white sail amongst the millions of white wave crests. We peered, saw nothing and then went around again. And again. The radio crackled again – the boat had called in. It was fine and heading into a harbour somewhere miles away. It was nowhere near our search zone.

Michael O'Neill, venue unknown, 1982 - Photo by Jim Abbott

The consensus was that we were not fans of long distance private light plane travel.

We went to Christchurch. The flight had taken 12 hours and the consensus was that we were not fans of long distance private light plane travel. Even less so, considering we were only halfway and had to return in the same underpowered airborne aluminium containers.

The Hillsborough gigs were sold out and we were saved financially. The time in Christchurch was largely uneventful. I spent time with Roger Shepherd and Hamish Kilgour. Our pilot made friends with the guy who owned the motel. We were not the first band there that month. Another band, a popular one who shall remain nameless – had been there and left behind several amateur porn videos and the landlord fired them up for all who were within visual distance of the TV. The band were completely horrified – in those pre-Internet days such things were rare and especially so for still naïve Catholic paternal-home-living teenagers from the North Shore. The pilot decided he wasn’t keen on coming to the gigs and decided to stay in his room and “watch TV”.

Chateau Tongariro, August 1982 - Photo by Murray Cammick

The shows over, Tom and Keith McFrenzy (our lighting guy) announced that, with their pay in hand, they would pay their own way north in an expensive, large and scheduled Boeing 737. So be it. They took the guitars and thus reduced our weight.

We took off, having convinced ourselves that this northward flight would be a happy new experience. And mostly it was – scenic, smooth and picture book. As we headed over the Strait the pilot turned and announced that we had plenty of gas and we had no need to refuel. Watching the other Cessna, it was clear they had made the same call and like us they would meander happily to Ardmore on the fuel they had onboard. Nobody complained, it was a lovely day and we were enjoying it this time.

The writer and Mike O'Neill, Devonport Domain, summer 1982 - Photo by Jim Abbott

Around New Plymouth it began to cloud up somewhat, with Mount Egmont (as it was still named then) just poking through. By the time we got to Raglan it was dense. We headed on but as we passed over the flat Waikato, the ground below was less and less visible, eventually disappearing when we were over Huntly. The pilot looked perturbed. The gas gauge was reading lower than he thought it should and we were now circling, looking for the home airfield. It was, he explained, “around here somewhere”, but the cloud had made it invisible. Why, I asked, didn’t we simply go through the clouds and look for it? Not possible, I was told – if there was a hill or a mountain through there we were instantly stuffed.

Peter van der Fluit, Devonport Domain, summer 1982 - Photo by Jim Abbott

We spiralled down and landed, with barely a few minutes worth of gas left.

Stuffed either way, we all mumbled back. I wondered where the parachutes were kept. We went around and around. The pilot was grey and the fuel pointer was flicking well into the red. “There!” said Hilary, and so it was. A small hole had appeared almost vertically beneath us and through it we could see a perfectly formed black runway. We spiralled down and landed, with barely a few minutes worth of gas left.

Tarmac had never looked so good.

However, we were alone. There was no sign of the other plane. Shit. Their fuel had probably expired too as we knew that they had also skipped the mid-journey refuel. An hour or so passed and we waited, hoping for the best but aware that the worst was a clear possibility. The phone rang – it was the other pilot in Hamilton. When the clouds began to intensify, he’d done the very smart thing, turned around and landed right there in Hamilton. He then managed to get Michael O’Neill, Peter van der Fluit and Tony Drumm to a bus terminal in the city where he placed them on a Railways bus north.

We took the van to Auckland railway station where we met them. We never hired a Cessna again.