Playdate magazine was New Zealand’s popular movie and music monthly in the Swinging Sixties. Although it was owned by the multi-millionaire cinema baron Sir Robert Kerridge, the magazine reflected the world view of its editor Des Dubbelt, an arts-aware man who embraced the energy of the decade that changed the world. He worked with young talent such as photographer Roger Donaldson and artists Gretchen Albrecht and Pat Hanly to document New Zealand in the 1960s.

The magazine began life in July 1956 as the slim, 40-page Cinema, before becoming Cinema, Stage & TV, costing one shilling. In May 1960 the magazine was renamed Playdate by new editor Des Dubbelt. The September 1965 issue of Playdate was a record 164 pages and the price had only increased by six pence.

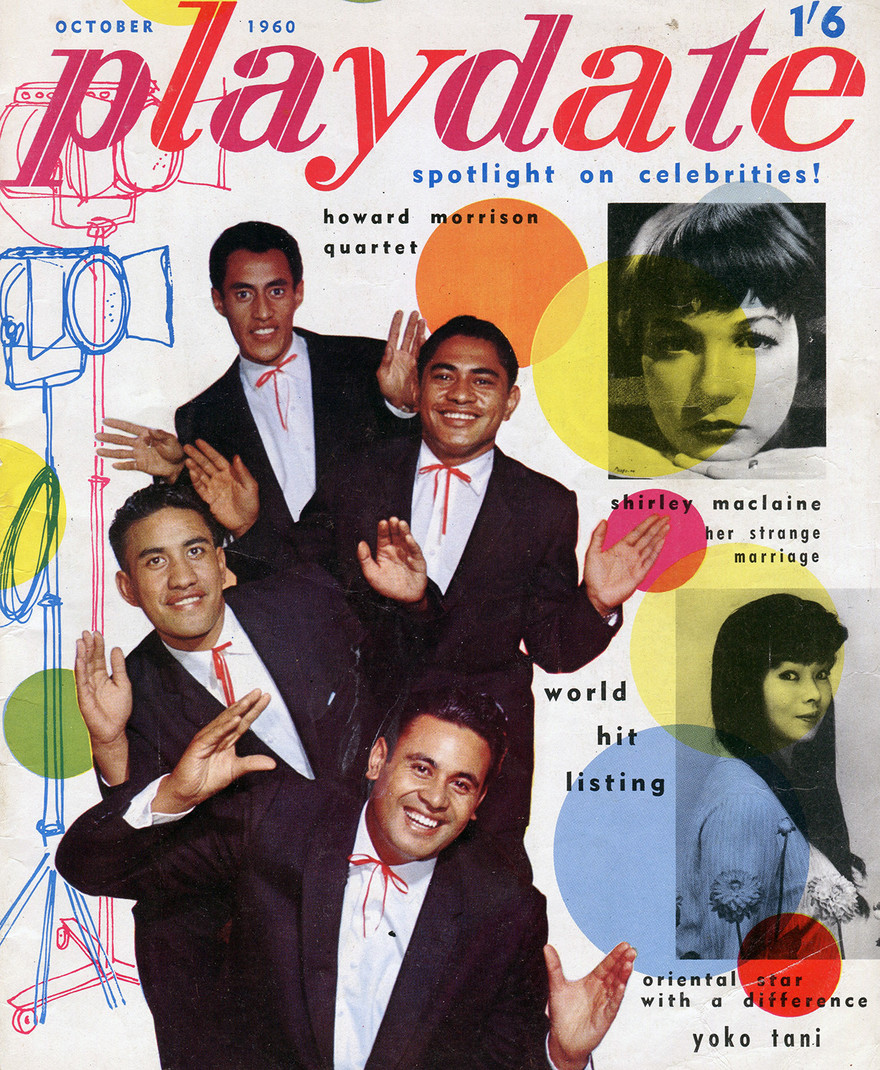

Howard Morrison Quartet, Playdate, October 1960.

The magazine’s title derives from the US entertainment industry term “playdate”, meaning the “release date” of a movie or the “performance date” of an entertainer. For example, some 1950s usage in a sentence: “Distributors are being provided with playdates of the movies in order to arrange advertising” or “Count Basie’s playdate in Chicago has not been announced”.

As youth culture boomed in the 1960s, Playdate documented the move from staid styles to mod fashion to hippie casual. The magazine’s initial focus was movies but it broadened to include music, fashion and youth culture.

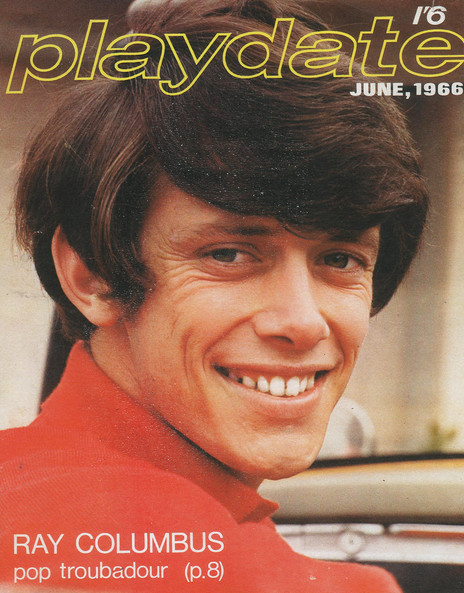

Playdate - June 1966, Ray Columbus on cover.

The synergy between movies and music was organic in the 1960s, as Elvis Presley evolved from rocker to matinee idol, James Bond had hit themes, Cliff Richard went on a Summer Holiday, The Beatles had a A Hard Day’s Night, Lulu sang To Sir With Love, we queued for Woodstock, we lied about our age to see Easy Rider and, lest we forget, the biggest movie of the 60s was The Sound Of Music.

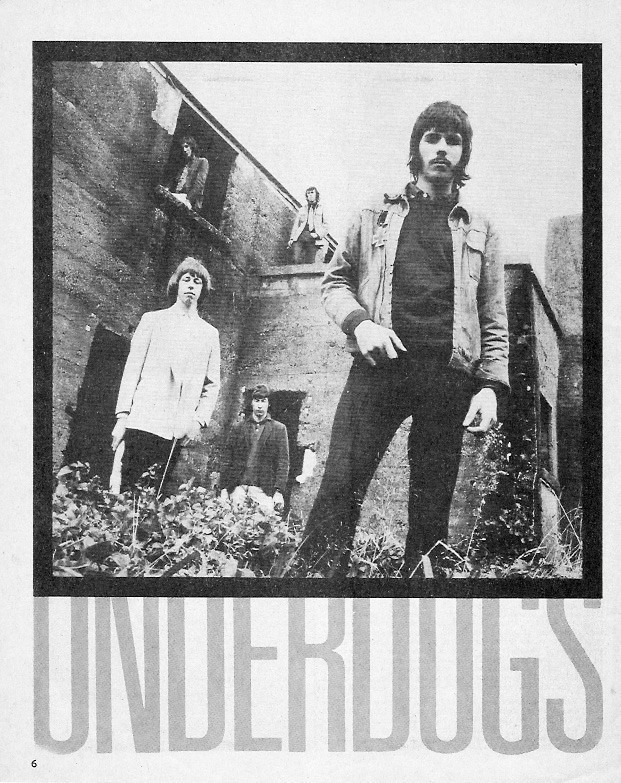

The Underdogs in a moody shoot by Roger Donaldson, Playdate, 1967. Caption: “The Underdogs are a minority group. They number five. The next world war will be number three. The Underdogs outnumber it. They are far out. They are so far out their fallout shelter falls in.”

Playdate’s music coverage including a significant documenting of the thriving local music scene including the venues, the local music TV shows and the hip fashion styles.

The magazine was published by the Kerridge Odeon theatre chain but the owner, Sir Robert Kerridge, had the good sense to allow Playdate to be comprehensive and to cover the movies released by his rivals.

In the 1960s, The Kerridge Odeon company moved into popular music with foreign tours including The Beatles and hosted nationwide tours through his movie theatres for the hit New Zealand music shows C’mon!, On Stage and Golden Disc Spectacular.

While Kerridge, Auckland’s most high-profile millionaire, held court at the top of his plush 246 Queen Street shopping centre, Playdate was a block up Queen Street, hidden upstairs in the St James Theatre building, surrounded by cans of film and a preview theatre.

AudioCulture spoke to former Playdate assistant editor (1967-1972) Tom McWilliams about life in pop culture publishing in the swinging 60s. He valued their distance from head office: “We were away from 246 in a tiny office with only a skylight, as the theatre’s facade blocked the view of Queen Street. A horrible office space but great fun.”

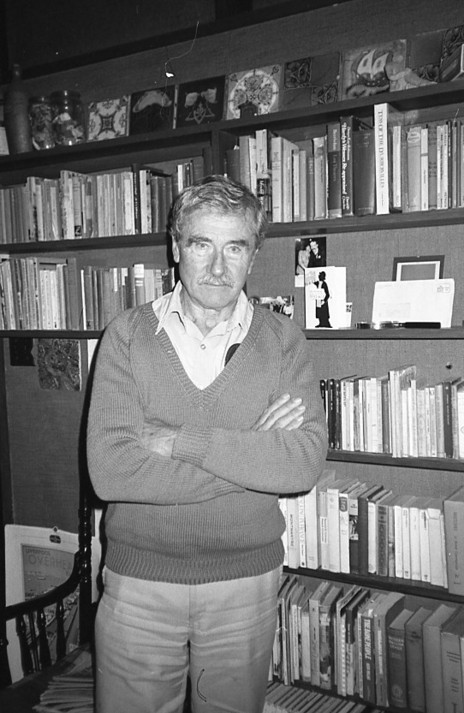

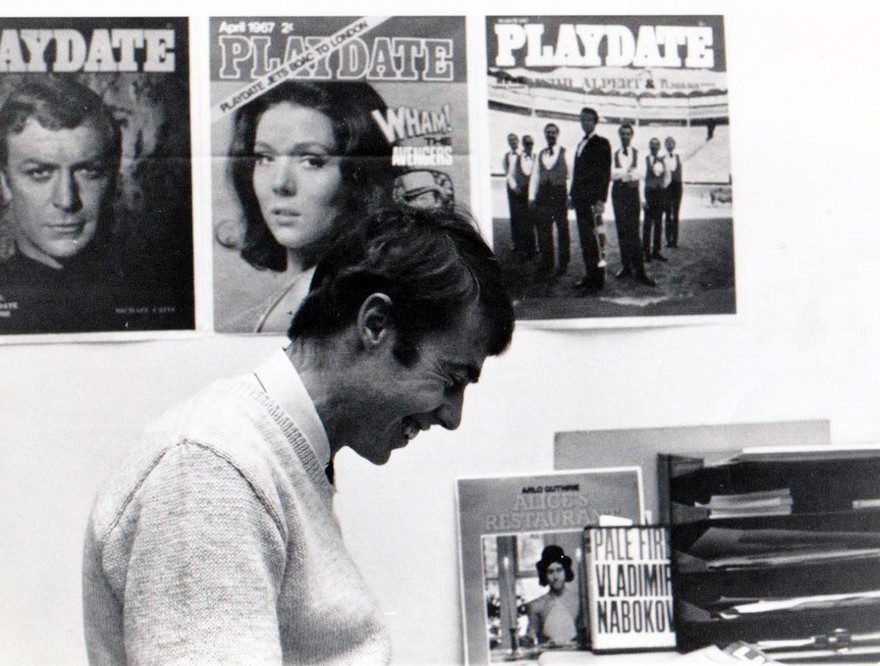

McWilliams still views his Playdate role as “the best job I ever had” and he heaps praise on the founding editor. “Des was a terrific guy, he played classical music on the piano – he absolutely loved playing the piano. He loved contemporary writing such as Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe and American culture, as well as Thomas Hardy, D H Lawrence etc. He was a literary man. Des was a good editor, not a corporate man.”

When wannabe writer Louise Warren joined Playdate in 1968 as editorial assistant, it was her first job. “Tom and Des were so laidback,” she said. “Des was a conscientious objector during World War Two and a real bohemian guy.”

“He wanted to be cutting edge.” Des Dubbelt, 1987. - photo by Chris Bourke

“Des was a magazine person, he loved Esquire,” said McWilliams. “I was mad keen on the New Yorker. He would have kept an eye on Playboy. He wanted to be at the cutting edge. He wanted to know what you were listening to – that was new.”

Llike the New Zealand culinary classic – meat and three vegetables – music magazines are too often quite limited in scope, often comprising just interviews plus news, reviews and a gig guide.

As Playdate started as a movie magazine its reach into pop culture extended beyond the confines of the music formula. “Des was into the arts,” says McWilliams. “He was ahead of his time, he expanded it out into a cultural magazine.”

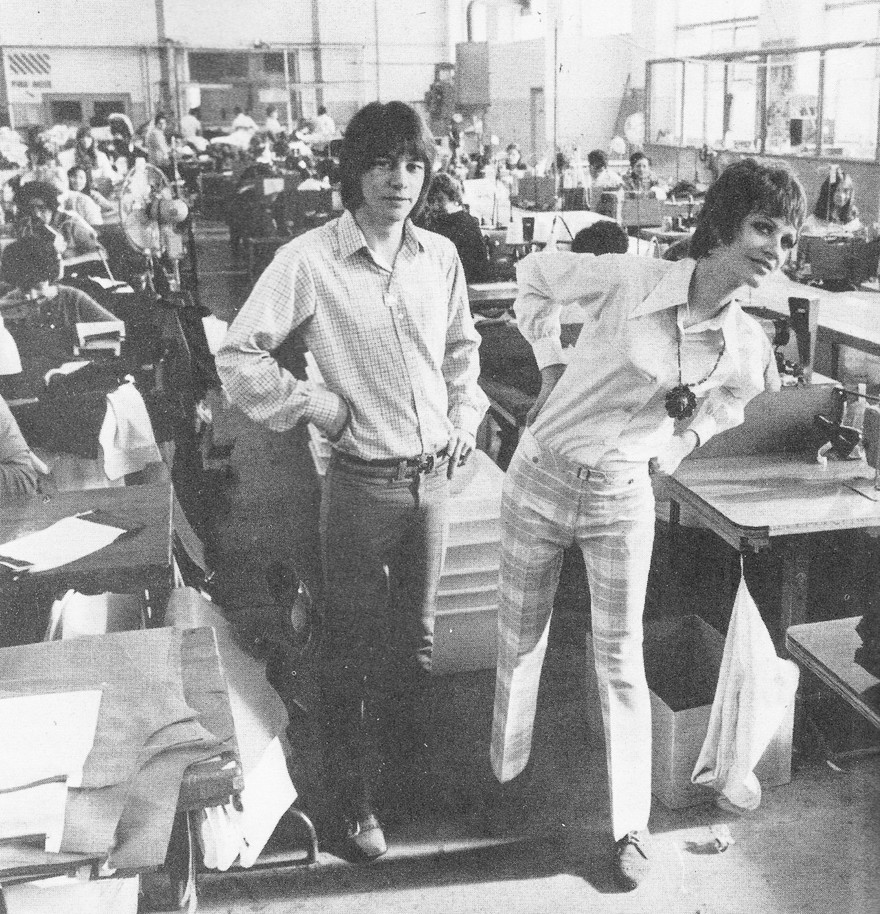

Playdate, August 1969, Shane Hales and Jacqui James (singer Jacqui Fitzgerald) in a Holeproof ad; photographer Kim Goldwater.

When a baby-boomer finds Playdate in a secondhand book store, it may not be the magazine they recall. Alongside pin-ups, there are stories on coffee bars, Elam Art students, boutiques, tattoos, nightclubs, surfing, high country tramping, slot-cars, Barry Crump adventures, hitch-hiking and overseas travel.

The back streets of Auckland were dotted with small boutiques that provided an alternative to the fashion choices offered by the large New Zealand manufacturers. The night life was also found in the back lanes and Playdate did major multi-page profiles of the nightclubs of Auckland, Wellington, etc.

“The best job I ever had.” Tom McWilliams, assistant editor, Playdate, 1968. - Marama Warren collection

Playdate was a large magazine with a staff of only five. The editor, two journalists, the ad man and the receptionist. Des Dubbelt was an active writer using the pseudonym “Our Man” on features and his initials “DGD” on reviews and he designed many of the feature pages. In 1960 “Our Man” visited as many Auckland nightclubs as he could in one night, to write “Auckland Tonight”, a feature about the city's buzzing after-hours scene.

“Des allowed the other two writers a lot of freedom in choosing content and working independently,” said McWilliams. “You were responsible for your own page – you wrote the piece, wrote the heading and organised the illustration. It was your page, but someone else read it before it went off to press. I was there for the movies and the opportunity to write and design my own magazine pages. There was a movie preview nearly every day of the week.”

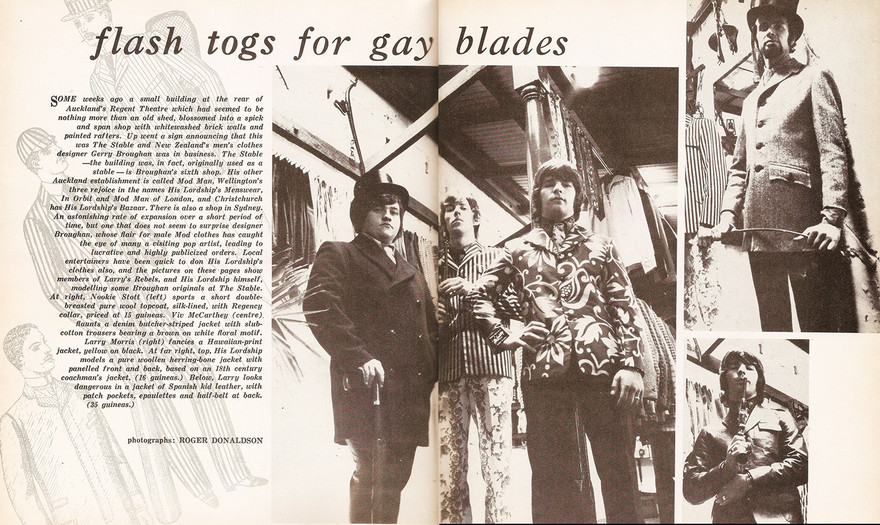

Playdate, May 1967: Flash Togs for Gay Blades, featuring Larry's Rebels. - Photos by Roger Donaldson

“Des chose the covers and he worked with the outside contributors such as young photographers Roger Donaldson, Kim Goldwater, Max Thomson and Rodney Charters. He was giving them their break, an audience, he was giving them good jobs to do. Des also allowed photographers to do photo-essays.”

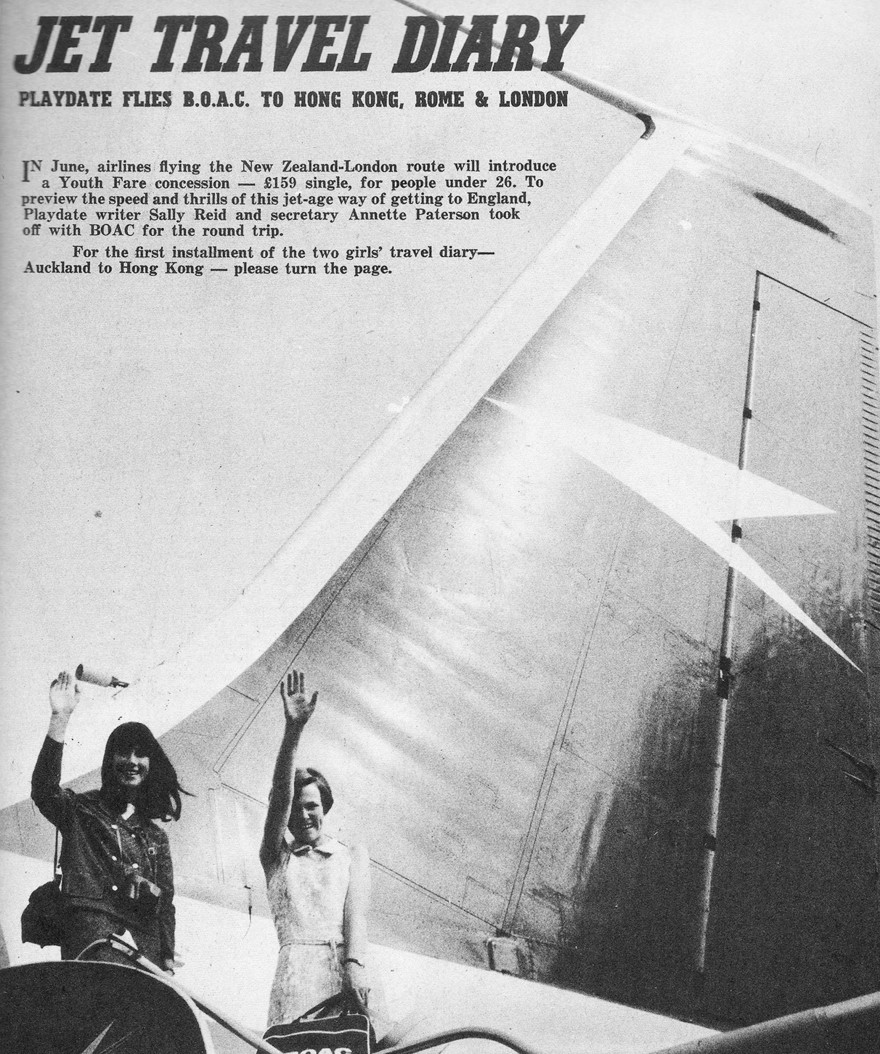

One editorial assistant, Sally Reid, was known for wacky, innovative ideas: she blagged free air passage to England and wrote about her adventures in swinging London. BOAC provided the air tickets and a photographer took the prerequisite selfies. When Reid left Playdate, she moved to London and worked at the Beatles’ company, Apple.

Playdate, April 1967: staff writer Sally Reid (left) and receptionist Annette Paterson score a trip to the UK through BOAC to write a Jet Travel Diary. Reid would later return to London to work for the Beatles at Apple.

“Des and I had morning and afternoon tea in his office,” said McWilliams. “Conversation with Des was great fun. When we disagreed it was even more fun. Des was a man of real moral integrity. He was horrified by Cat Stevens’ ‘I’m Gonna Get Me a Gun’.” (Dubbelt was a conscientious objector during the Second World War.)

When Louise Warren joined Playdate in 1968 she knew her music – her father was jazz musician Jim Warren, who wrote jazz reviews for the magazine. “Des and Tom were the most wonderful mentors, they set about giving me an education in music and I saw about three movies every week. They taught me the basics of layout and design and interviewing skills. It was a dream job. Not long after I started the job I got to spend the afternoon with Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, me and them in the hotel foyer. They were just so kind to me.”

“It was a dream job.” Louise Warren, Playdate editorial assistant, 1968. - Marama Warren collection

“I did a swimsuit shoot once out at Swanson with Roger Donaldson,” said Warren. “Des always had a part to play in it. Des always got the sexy angle, somehow.”

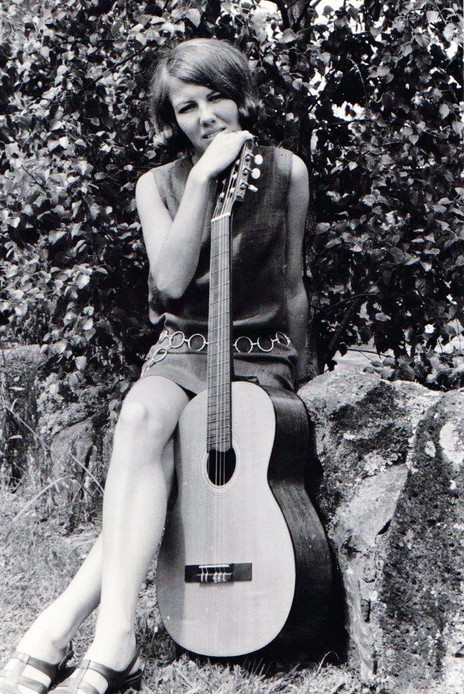

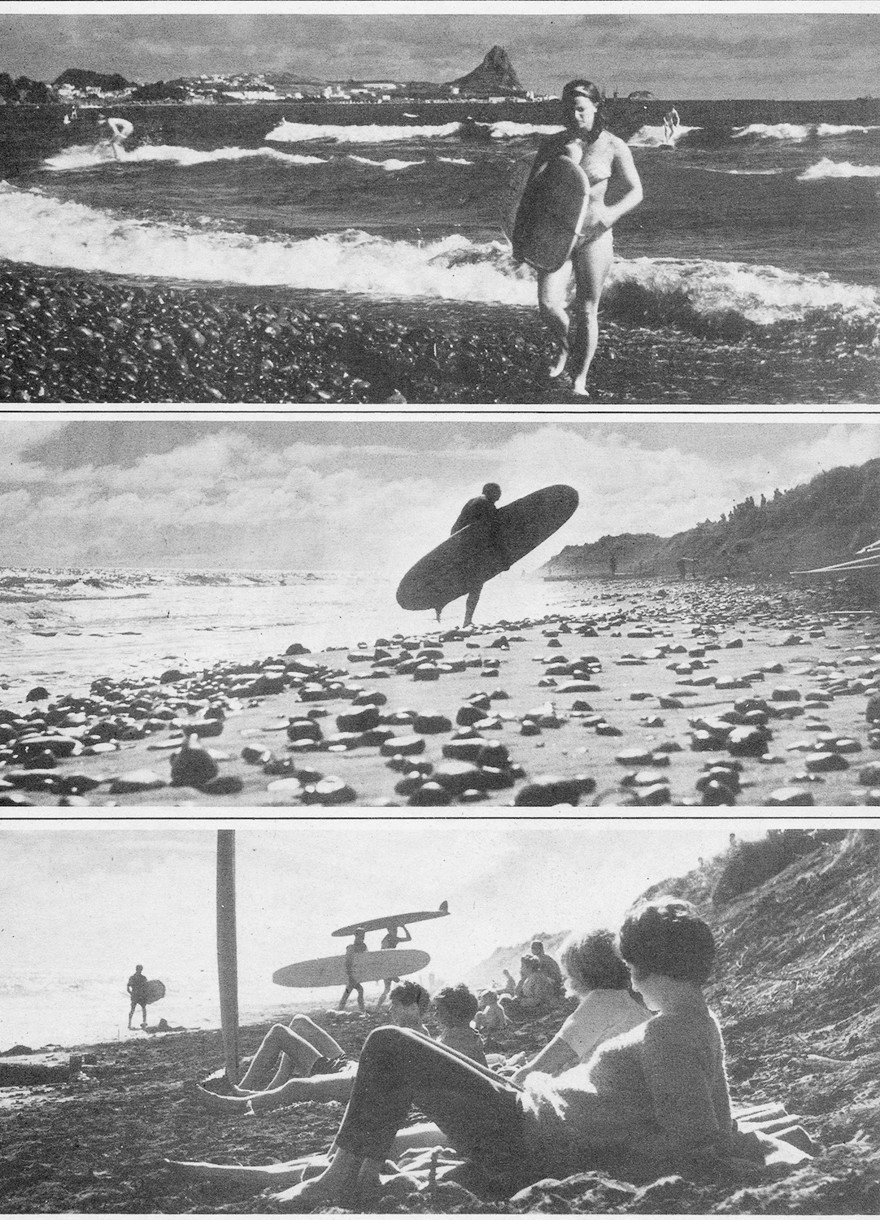

Part of the magazine’s documentation of the 1960s were the swimwear shoots, the lingerie shoots, the summer beach bikini competition, Miss New Zealand pageant, woman surfers, topless swimwear at the Loft Record store etc. When Russell Brown interviewed Des Dubbelt for Planet magazine in 1994 he noted that Playdate, like most street fashion media, opted for “any old excuse for a bit of semi-nudity”.

In Planet magazine Dubbelt spoke of his magazine’s mid-60s success: “By the time the Beatles thing arrived we were very well established as the magazine for that generation. In its heyday, Playdate sold about 120,000 copies a month.”

Dubbelt described the arrival of photo-offset printing: “That was great. Being able to bleed all around and through the gutter and overprint with different tones. It was a big breakthrough from the old letterpress days and from the very conventional sort of layouts.”

When The Face magazine emerged in the UK in 1980, Dubbelt welcomed the fresh face of pop culture: “I thought, well, this is the revolution.”

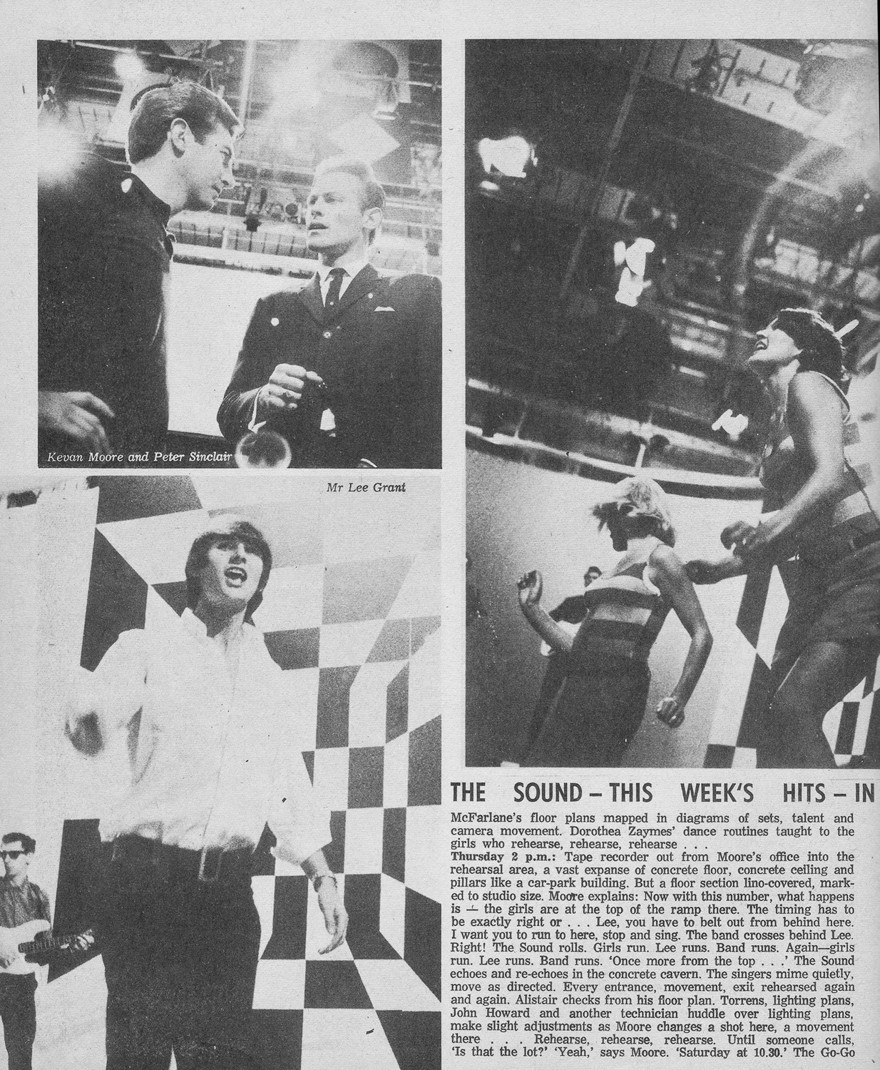

The success of the C’mon pop TV show was celebrated in Playdate with a photo-spread shot at the Shortland Street studio and pin-ups of Mr Lee Grant, The Chicks, Sandy Edmonds, Larry’s Rebels and others.

Playdate celebrates the C'mon TV show, April 1967. Top left, producer Kevan Moore and host Peter Sinclair; below, Mr Lee Grant.

Prior to joining Playdate in 1967, Tom McWilliams had been a TV graphic artist. He thinks the earlier TV show In the Groove has been overlooked. “I thought it was great. I’d go in on the weekends when they were recording – I saw The Crystals, Gene McDaniels, Jimmy Rogers, Dinah Lee, etc.”

Dubbelt was not the only Playdate staff member to have highbrow hobby. McWilliams had a side-line and labour of love, editing the literary magazine Mate from issues 14 to 20.

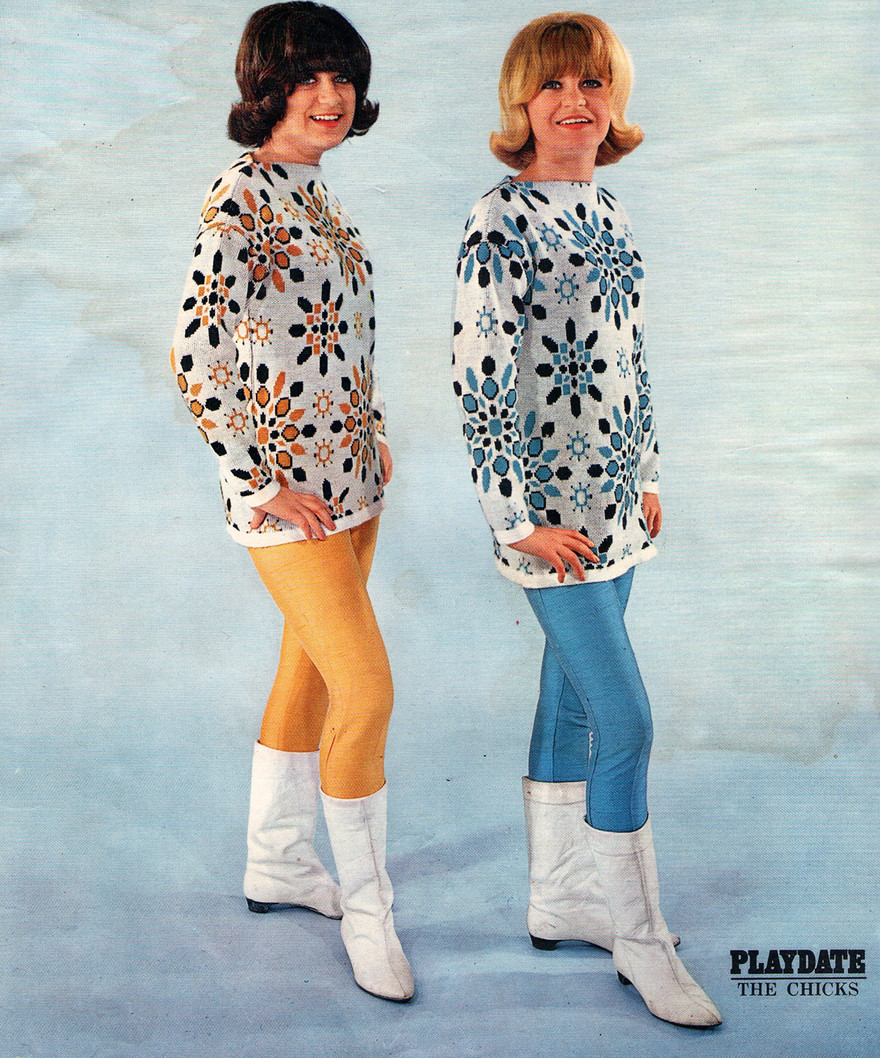

Playdate was used by clothing manufacturers to reach young women and sell their new season styles. Some adverts placed by the large clothing manufacturers looked very staid. The magazine’s fashion editorial regularly sourced fresher designs from local indie boutiques such as Hadny 5 (designer Isabel Haworth), Annie Bonza, Paraphernalia, etc.

As protectionist government policies banned the importing of clothes, the 1960s Kiwi teens had to accept local knock-offs of London’s Carnaby Street styles or they had to go DIY on mum’s sewing machine.

The Chicks as Playdate pin-ups: flower power. - Judy Donaldson collection

Bob Harvey, a young advertising executive, kept the Playdate adverts fresh and hip for the “Maggy” brand. He even used Māori models as part of a May 1967 advert for “Maggy”. Like Dubbelt, Harvey was a Westie and enjoyed walking in the Waitakere Ranges.

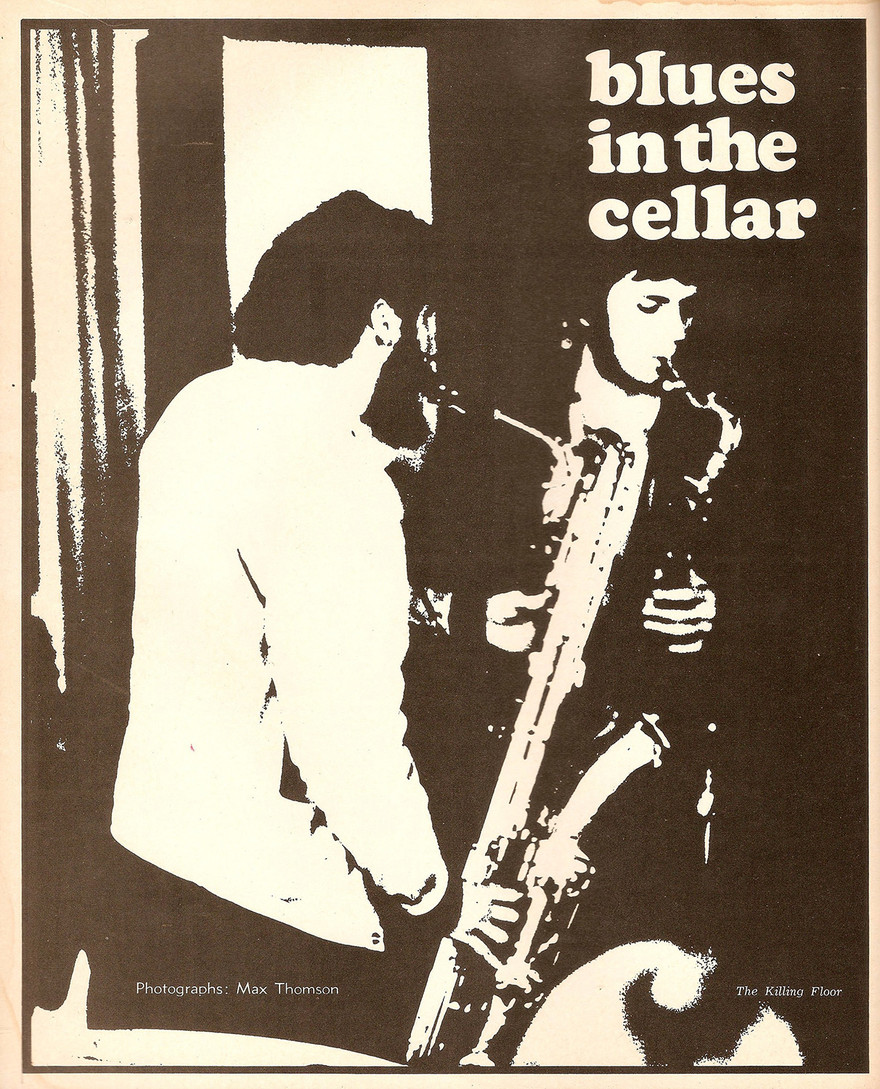

When former Pleasers drummer Max Thomson knocked on Bob Harvey’s door at McHarmons Ad Agency with his photography portfolio, Harvey gave him some work and sent him to see Des Dubbelt. Photographer Roger Donaldson was about to move on and Thomson became a regular contributor to Playdate, shooting numerous fashion shoots, the Four Tops, Jethro Tull and a “Blues in the Cellar” feature.

Playdate, September 1969: The Killing Floor in 'Blues in the Cellar' feature, with photos by Max Thomson.

It was not until October 1967 that New Zealand ended its draconian law that required hotel bars to close at 6pm. Teenagers or anyone who wanted somewhere to go before or after a movie went to a coffee bar – a natural home for folk music, jazz music, cigarette smoke and a bohemian lifestyle.

Five years earlier, in October 1962, the inner-city coffee lounge The Artist – usually a venue for live music – became a theatre for the Auckland University Drama Club production of Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story. Playdate reviewer wrote: “Produced with a craftsman’s skill by Dick Johnston and superbly acted by Eric Woofe and Max Calvert, The Zoo Story emerged as the season’s most successful dramatic experiment.”

Also from 1962, in the April issue, the Bel Air coffee bar sketches of Playdate contributor David Eastman are eulogised. “The calypso group filled the room with its bongo-pulsing rhythm.” The story ends as well as it starts: “... sometimes right into the morning hours – he haunts the city’s coffee bars, just as artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec did the music-halls of 19th century Paris … observing. And sketching.”

Playdate had a healthy coverage of the surf scene throughout the 1960s, including a photo feature on women surfers. A major feature was devoted to Tim Murdoch upon the release of his surf movie Out Of the Blue. Several years before Murdoch became the head of Warner Music NZ, he was described as a “surfing’s prophet” by Playdate (January 1969). His future film projects included Captain Cook (“He was a very cool guy”) and what he called “mind-shows – entertainment for the now, now, now.”

Playdate, June 1965: ‘Surfies, No Surf’, a photo feature by Rodney Charters.

A 1965 advertisement to encourage young women to save has images of “Denise and her exciting future”: car ownership, travel and her wedding day. The editors of Playdate depicted a more modern young woman: twisting, hitch hiking and surfing.

By the end of the decade there was a chasm between the conservative styles of the New Zealand clothing manufacturers and the youth culture that was represented by the movie Easy Rider (1969) and rock icons such as Jimi Hendrix. As Playdate magazine embraced the music of the Woodstock generation, large local manufacturers gave up advertising to the jeans and T-shirts generation.

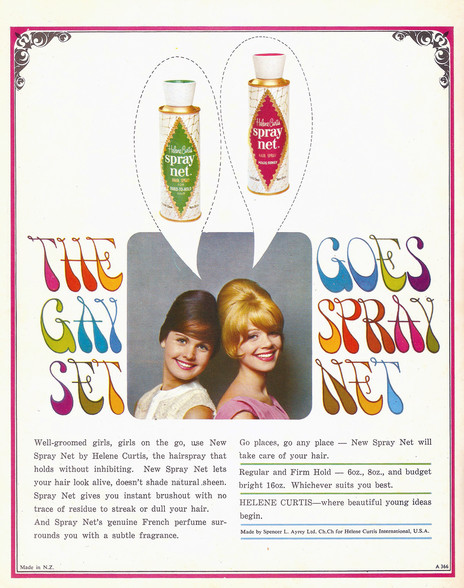

The financial strength of Playdate came from the massive volume of advertising of fashion, jeans, footwear, hosiery, lipstick, hairspray targeting young women. But by the end of the 1960s, there were two new magazines for younger women: the monthly Eve (1966-75) and the weekly Thursday (1968-76).

Playdate, September 1967: the gay set goes spray net.

“You knew by the size of the issues that our flood of advertising was over,” said McWilliams. “And there was difficulty in knowing what audience to aim for. Pop music split into bubblegum and darker stuff, with Jefferson Airplane’s ‘White Rabbit’ an early example of psychedelic rock. And, like the music, most of the best movies of the 70s weren't for aiming for family audiences any more.”

Playdate was sold to the Auckland Star in 1972 and six months later the magazine was closed down.

“Des was disappointed,” said McWilliams. “We all were. It had been a great gig. Des moved to Britain with his family and found work there. I moved on to the New Zealand Listener.”

Hot Licks would follow in 1974 and Rip It Up in 1977, but compared to Playdate the later titles were meat and three vege music magazines.

--

Thanks to Bill Gosden

--

Chris Bourke: A Date with Playdate, 1987

Russell Brown on Des Dubbelt and the street press, 1994

Des Dubbelt: NZ Herald obituary by Tom McWilliams