I was mad for How Was The Air Up There? – the K-tel Records compilation of indigenous 1960s sounds released in New Zealand in 1980. It was New Zealand’s Nuggets and my friends and I played it relentlessly and bought the Ray Columbus and The Invaders and La De Da’s compilations that came in its wake.

At the same time as Ripper Records, Propeller Records and Flying Nun Records were opening ears to New Zealand punk and post-punk sounds, a past just as rich and alluring revealed itself. Soon Peter Nelson and The Castaways’ ‘Down In The Mine’, The Avengers’ ‘Love Hate Revenge’, Ahmed Dahman Band’s ‘Stage Door’, Chants R&B’s ‘I’m Your Witchdoctor’, The Fourmyula’s ‘Nature’, Larry’s Rebels’ ‘I Feel Good’ and The La De Da’s ‘How Is The Air Up There?’ were as well played around our house as The Clean, Tall Dwarfs and The Screaming Meemees.

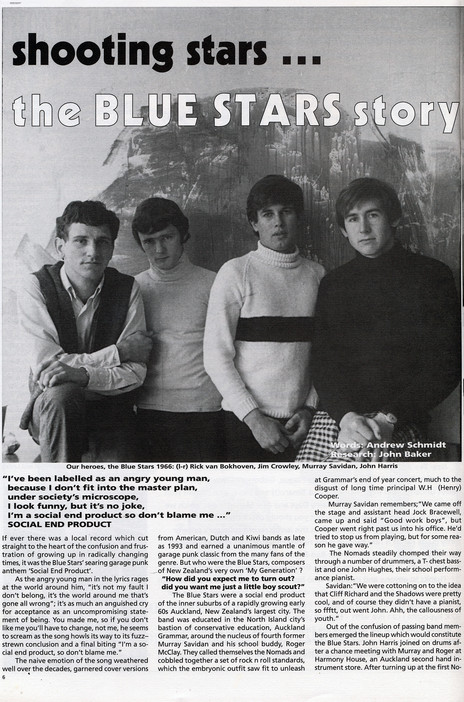

While the post-punk records kept right on coming, our 1960s musical heritage proved stubbornly elusive. There was the stray track on Raven Records’ Ugly Things compilations, including The Blue Stars’ angry piece of Who histrionics, ‘Social End Product’, Ray Columbus and The Art Collection’s psych-punk ‘Kick Me (I Think I'm Dreaming)’, Chants R&B’s ‘Neighbour Neighbour’, House Of Nimrod’s ‘Slightly Delic’ and The Dave Miller Set’s ‘Mr. Guy Fawkes’. Raven even got as far as compiling and releasing Larry’s Rebels, The PleaZers and Max Merritt and The Meteors.

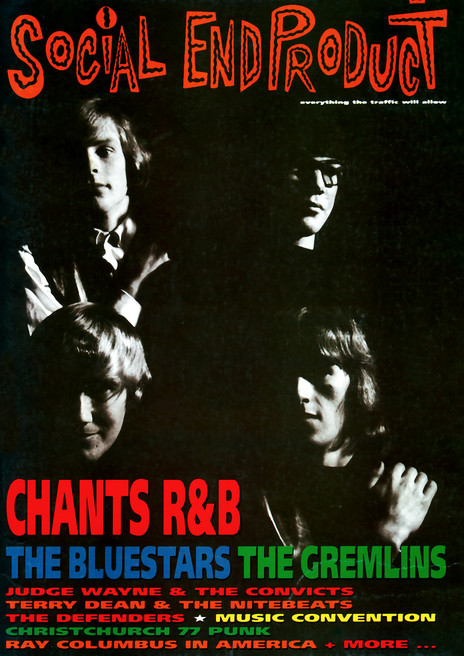

Social End Product

Surely there couldn’t be much more, I thought. Then in August 1988, John Dix published his New Zealand rock and roll history, Stranded In Paradise, and laid bare the real riches for all to see. My brother Stu and I passed that book back and forth one chapter at a time until we finished it.

Meeting John Baker at the seedy Subway in Christchurch in 1990 provided an opportunity to dig deeper. I was there to interview him about his garage punk group, The Psycho Daizies, for Monitor, the Auckland student station 95bFM's magazine.

In a fiery set, the raw quintet played Texas garage punkers Kit and The Outlaws’ ‘Don’t Tread On Me’, something I mentioned to John later that night in a Munster Mansion on the far side of Hagley Park.

He’d been razzing me up until then with smart interjections from passing band members. Bass player Rich Mixture, who ushered me into a car after the Daizies’ storming show, was the nice guy. They had all the bases covered.

When Warwick Roger assigned an arts column to me at Metro – the magazine I worked for in 1993 and 1994 – my mind flicked quickly back to John. I’d already sold a story on him and garage punk to the NZ Listener.

Ever since John Dix’s Stranded in Paradise, I’d been waiting for the rock culture stories to flow, but few had.

The recent death of rock and roll pioneer Tommy Adderley begged an in-depth look at his life in New Zealand and despite Metro having made a snide dig at the dead Adderley’s drug habits in the mag, I asked if I could write an obituary. After some thought, it was okayed.

I was amazed no one else had thought to do it. Ever since John Dix’s Stranded in Paradise, I’d been waiting for the rock culture stories to flow, but few had.

As Adderley began his musical life in Wellington, I asked if I could go down there. They put me up in a fancy hotel above the Terrace, where I never could relax, and I was soon out and about.

First stop was the Alexander Turnbull Library, which provided yet more bits and pieces, but no clear timeline, so I got on the phone to Tony Eagleton, a Wellington rocker of the 1950s and 1960s. We met up in a bar off Manners Street frequented by the city’s large contingent of aging rockers.

Tony seemed more interested in talking about himself than Tommy and I was slowly getting pissed off, when a bearded guy across the bar motioned me over. It was Billy Brown, a jazz drummer who knew Adderley well. He gave me a name to look up in Auckland.

Then it was into the hills above the city to see rock historian Roger Watkins. Roger was wary and gave me little, but he did play Adderley’s shock 1960s American and Canadian hit, ‘I Just Can't Understand’.

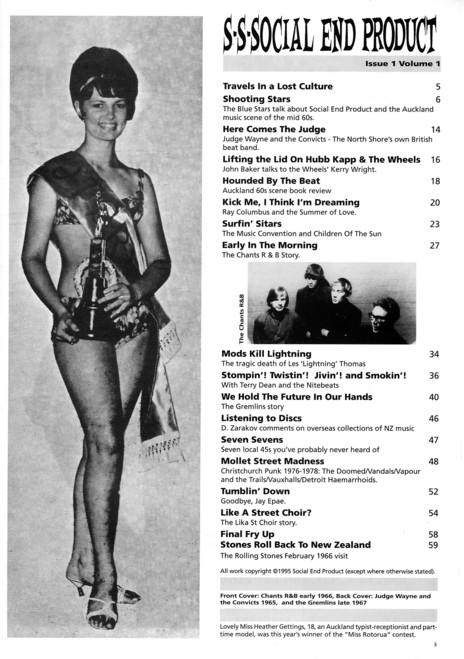

Contents page

In Auckland, I pursued David Gapes, one of the founders of pirate station Radio Hauraki and more recently editor of OnFilm. Gapes was a close friend of Tommy’s and reluctant to talk. He finally took my sixth call and immediately brought me to task for the dig at Adderley that we’d run. I sighed and told him that wasn’t me. I felt like a kid caught in the crossfire between warring adults. Gapes then softened and answered the questions. When the story was published, he rang up and thanked me on behalf of Tommy’s friends.

The story’s timeline was still not clear, with chunks of Adderley's eventful existence missing, so I got on to John Dix, who was then editing music freebie, Real Groove.

We met in a pub on Queen Street. John was open and friendly and a little surprised I didn’t want a drink. It was still morning, I told him, although the truth was I never drank in work time.

Dix was free with his knowledge and anecdotes, and refreshed, I lined up interviews with sixties pop star Larry Morris of Larry’s Rebels, and bass player-producer, Billy Kristian, who had success with Ray Columbus and The Invaders, Max Merritt and a US-based group called Night.

The first time I saw Larry Morris, he was standing in blue jeans and trainers in the godly view from his ridge-top Orakei house in the hard white sun of early winter, framed by the sea-lanes he sailed as a merchant seaman, looking out past Waiheke Island, where his parents now lived.

Morris was a hard nut who helmed New Zealand’s toughest pop band of the mid to late sixties. It seemed the perfect tableau. A lost and fallen sixties pop star returning in the wake of tragedy. It’s only when the conversation turned a dark corner to Tommy Adderley’s death and the package tours they were both regulars on that I remembered he was also back in the city that jailed him then turned its back in puritan disgust, consigning him to the dead grey world of faded stardom.

Adderley died shortly before Morris’s return to Auckland and it’s obvious Tommy’s death had given him pause. He cried several times, left the room once when overcome with grief and seemed wounded that no one had thought to notify him about Adderley’s death sooner. He’d only just missed the funeral, but had made the belated Easter Weekend wake that brought together much of our 1960s pop aristocracy.

They were fellow travellers, those two. When Nicola Legat interviewed Adderley on his release from prison for drug offences in the early 1980s, Larry Morris was there riding shotgun. Still was, it seemed.

Larry told me to ignore the drug shit about Adderley. “I’m not going tell you anything about that.” It sounded like an overreaction. But maybe he has a right to be tetchy. He’d been stung hard by drugs convictions: his first in March 1973 wiped out his career. His second, soon after, landed him in jail for seven years for selling LSD to an undercover policeman.

Billy Kristian proved a much more difficult nut to crack. He reluctantly agreed to talk, but when I turned up at his Kingsland studio, he left me there with his scrapbooks and disappeared.

With the rock and pop Adderley covered, I turned to the jazz and cabaret Tommy, hitting up all-round performer Chic Littlewood, and Jack Friedlander, the old time jazz pianist that Billy Brown had hipped me to for comment.

Littlewood was lightweight, but Friedlander was a real gem. He was a former racing journalist who played jazz in the 1940s in his father’s group in Christchurch. Recently, he backed Tommy at jazz festivals around the North Island.

Friedlander asked for money, and when I refused, he smiled and lead me into a room crammed with sheet music. Jack didn't miss a beat. He moved through into the lounge, sat at his piano and started pumping out ‘A Train’. I had to leave, but as I was walking up the steep drive, I could still hear him playing.

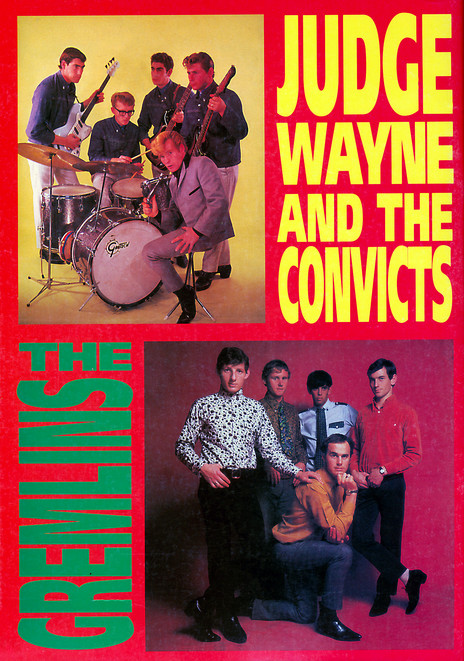

Judge Wayne and the Convicts and the Gremlins gracing the pages of Social End Product

The story was nearly complete,with only Adderley’s partner and his former wife left to interview. Pam, his ex, and the mother of his son had been with him during his early junk years and was now a real estate agent on the North Shore. She seemed more interested in damage control.

Adderley’s current partner was a nurse, who’d been with Adderley up to his death. I found her at their art deco flat across the road from the Gables Tavern on Jervois Road, where Tommy had been singing the day he died. She was surprisingly candid and still clearly in love with Adderley.

The resulting story, “Knee Deep In The Blues”, was the best non-personal piece I did for Metro.

John Baker got onto me again via Crawlspace Records, shortly after I left Metro in 1994, and proposed a magazine about the 1960s in New Zealand, a magazine about garage punk. He had a satchel full of written interviews with dozens of the protagonists that I read avidly. The scenes and memories, the records and clubs and wild teen times were all in there. The beginnings of a book definitely, although there was still plenty left to do.

John was living in a disused paint and panel shop in Kingdon Street, Newmarket, crammed full with pop memorabilia and records. There were old amps everywhere. A few hollow body electric guitars. The walls were plastered with music posters and Playboy centrefolds. A vintage stereo with big speakers had a huge stack of CDs and records around it.

The centerpiece of the magazine was to be an enormous feature on Chants R&B.

We’d meet up and plan the new magazine that we were going to call Social End Product. At the same time, John was waiting for a bank loan to come through. He had another Wild Things compilation due and our South Island research trip to finance, although I always paid my own way.

The centerpiece of the magazine was to be an enormous feature on Chants R&B, the wild Christchurch R&B group who unleashed the snarling garage classic ‘I’m Your Witchdoctor’ on indie label Action Records in 1966. John was obsessed with them.

That’s why I was leaning back in the front seat of a drab green Holden Belmont in November 1994 as John and I headed through Christchurch streets to John Dalton’s. Dalton was a die-hard Chants fan and former city long hair. His tale, like so many we’d hear, was as much about teen and post-teen life and the gangs and highs that people and sustain it as the music.

Dalton had been the secretary of the New Zealand Pretty Things fan club, and a sometime musician, hanging with the other hardcore Chants fans at the Stage Door, a black-walled basement club in Hereford Lane near the city centre.

The basement space was still there. We visited it later that day. It was a bar and grill storeroom now although little seemed to have been changed from the club days. The interior was still matte black and up in the cross beams you could see graffiti from the time. One scratching mentioned Bad Al and hash. (Ten years later, I met Al in Dunedin and he told me about his time as a young mod in Christchurch.)

Another former long hair, Davey Johnstone was operating the sound desk for The Squirm at Warners on the square that evening. John managed a few words and an interview was arranged for the next day.

Johnstone was a founder member of The Epitaph Riders motorcycle club. He parked his motorbike inside. Another room was full of sound equipment and his drums. He’d been to Europe in the 1970s and mixed sound for second division Kraut rockers Jane, whom he brought to New Zealand for a tour in the 1980s.

We stretched out the next day over the coastal flats below Christchurch to Timaru, where John’s friend Warren had the record freak oasis, Rhino Records. On the TV above the counter, The New York Dolls strutted out ‘Personality Crisis’ and Martin Phillipps walked the Otago Peninsula to ‘Pink Frost’. Then Bored Games fired up the then little seen ‘Happy Endings’.

We were in Dunedin by early evening and headed out to dinner at a Chinese restaurant up from the Octagon, where we ate and talked to proprietor Eddie Chin about the teen dance clubs he ran in the city in the 1960s.

Afterwards, I headed out to see King Loser, who were playing in the cellar bar of the Provincial Hotel in Stafford Street with George Henderson of The Puddle opening. I’d only ever been in that pub once before for a beer after a show at Chippendale House in Stafford Street.

The public bar was occupied by regulars and there was no stage. Shit. I thought I saw a couple of music people enter, but lost sight of them. Then just as I was wondering if I had the wrong venue, a big group of op shop wearers walked in and disappeared into the floor at the entrance end of the bar. I grabbed my beer and made my way to a stairway that led down to a pillared club with fake brick walls. It looked like an idealised Cavern. There’s a heap of people in there, Roy Colbert amongst them.

King Loser clearly hated each other. Celia was getting all wild and witchy on the organ, jamming a match between the keys to get a sustained drone. Chris was being competitive and giving it all, backed by drummer Steve Pikelet. I looked around once and saw Roy smiling a blissful smile and clutching a dewy handle. John didn’t turn up until late.

We were up early the next morning to sift through Otago Daily Times archives for dates and rare interviews before decamping early evening to a musician’s night in South Dunedin, looking for sixties people. John found a couple, but no one to get too excited about.

We were going to interview Jim Tomlin later that night. He was an original member of Chants R&B and then head of art at Dunedin Polytechnic. Tomlin lived in a beautifully designed house on Maori Hill. All bare wood board and fine sculpture in softly-lit alcoves. He leant back in his chair, his face half in shadow.

Tomlin played the slinky R&B lead on Chants R&B’s ‘I Forget How Its Been’, the original song they recorded after their win at the 1964 Christchurch Battle Of The Bands at Addington Show Grounds. It’d long been thought lost until John flipped the reel-to-reel tape Jim loaned him and found it on the other side. The tape also contained an explosive Chants live show from 1966 and two interviews with the group. At one point, Tomlin suggested we write a history of potting in New Zealand, saying it was sadly overlooked. But you could tell he was enjoying this as much as we were.

Social End Product interviews The Bluestars

We left for Invercargill early the next day as John had interviews jacked up with Bari Fitzgerald of The Unknown Blues and Ron Jenkins of Tomorrow's Love, an obscure Hamilton based group who recorded a scorching cover of Love's ‘7 And 7 Is’.

On Invercargill’s flat streets we found Ron trying to break into his house. We watched him from the across the road until John decided to approach. Jenkins already had a window open by then and needed a leg up.

Inside, the living room was crammed with acoustic guitars in various states of repair. There was a stack of sheet music on a large wooden stand. Jenkins was teaching himself Leo Kottke so he could leave the freezing works and play in pubs.

Bari Fitzgerald of The Unknown Blues was a freezing worker who spent the off-season hunting down obscure blues and folk records in garage sales and second hand shops and restoring Dodge V8s. We found him next.

We slept in the car that night somewhere inland from Gore, then kicked on to Timaru, where we stayed with Paul and Lynn Fisher. Paul was a die-hard Chants R&B fan from Stage Door days. He met Lynn there. They moved south in the early 1970s and Paul became a renowned potter before becoming real estate agent. He also played guitar in Catholic Taste and FN99. His memories of Christchurch were sharp and still barbed with the animosities of the time. He had many of the records he listened to then, he told us, then plugged in a guitar to bang out some fine Pretty Things. I retired early leaving John and Paul to talk deep into the night.

Retired Ashburton Town Clerk Peter Collins had another life in the 1950s and 1960s as the leader of Peter Collins and His Deaconaires, who released two singles. John was interested in ‘Fire Devil’, the B-side of their Universal Records release, ‘Diamond Lil’. It’s a fiery punkish track. Collins was thrown by John’s knowledge and enthusiasm and took a while to warm to us. But warm to us he did and the stories came tumbling out: the shows, the venues and the musicians he played with. He still had all his gear and an acetate of his Deaconaires’ third, unreleased single. Bless him. The old rocker.

In Christchurch, on the rebound, we met up with Max Taylor, bass player with Tomorrow’s Love in his suburban home, then tripped back into town for Tony Peake, a pioneering Christchurch punk, who was home from Sydney to set up a nightclub.

We met him upstairs where he ran through the rich story of The Vandals, Street Of Flowers and The Newtones. His memory was sharp and so were his anecdotes. We found Newtones and Vauxhalls drummer Martin Archbold at home clipping his wife’s poodles in the garage. You’re late, he said, as we retired to the house for a cup of tea and a chat.

In marked contrast, Al Park looked like wiry mangled Keith Richards, a comparison made easier by Park leaning against a poster for Talk Is Cheap. We were upstairs at Echo Records in the city centre talking about his role in Mollett Street, the bohemian rock club that fostered Christchurch punk, and his first group, Vapour and The Trails, pub rockers with attitude and energy.

Al was a 1960s teenager fired up by the R&B of The Rolling Stones and The Pretty Things, but too young to play back then. It was only when he got to Christchurch in the early 1970s that he picked up guitar seriously.

He was one of the clique who set up Mollett Street as a performing arts venue, and Vapour and The Trails played there regularly before graduating to the pubs, including the DB Gladstone, which Al also booked. Vapour and The Trails played to packed houses and recorded some originals along with covers such as The Heartbreakers’ ‘Get Off The Phone’, although only one weak track ever emerged on a compilation.

Violet Faigan, Dwayne Zarakov’s sister, invited us to dinner that evening, where we met Jon Bywater, the arts writer and critic, Brother Love Martin Henderson, bass player with The Axel Grinders, and Zarakov, who ushered us into his bedroom to listen to his sprawling eclectic music collection.

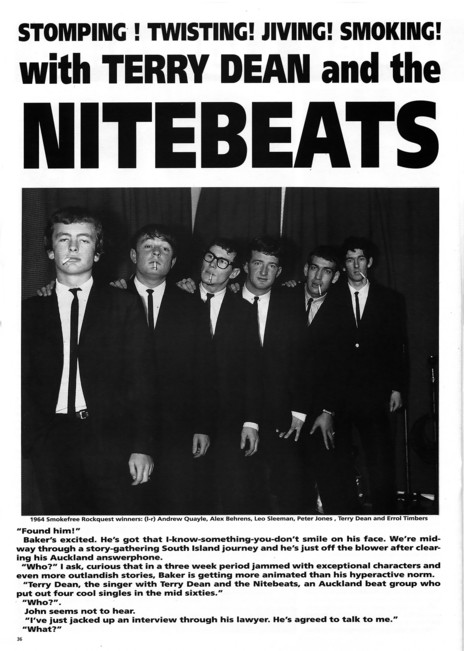

Social End Product - Terry Dean and the Nitebeats

We cut out early for an interview with a former 1960s radical, jacked up through John Lloyd, guitarist with Salvation, whom we’d met earlier that day (although when I can’t remember exactly; our days were crammed so tight). I thought it’d provide valuable context. And it did. We saw a documentary about the Progressive Youth Movement (PYM), the New Zealand equivalent of America's radical SDS, who were protesting the Vietnam War and for other causes. I wish we’d dug more in that fertile ground. I read every book I could find on the American counter-culture and radical student movements at university and always wondered whether something of the sort happened here. John wasn’t so impressed. The inner city alternative lifestyle with chickens was too hippie for him. And radical politics? Nah, John preferred the less bohemian 1960s, its early teenage years.

It was a relief to get back to Wellington, where we had dinner at the Green Parrot in lower Taranaki Street. We stayed with Gerald Dwyer in the amazing three-storey house in Brooklyn he shared with Sue Forbes, a Wellington pioneer punk, who sang in Life In The Fridge Exists, and Nigel, the singer from Head Like A Hole, who worked for Dwyer’s poster sticking company when not performing.

Next morning, it was on to the club in Cuba Street that housed Ali Baba’s nightclub (later the San Francisco Bath House), where The Avengers recorded a live album in 1968. It was seedy and the carpet was sticky so we retreated quickly to Slowboat Records. I spent the afternoon in the Alexander Turnbull Library going through copies of Playdate, the teen magazine of the time. John headed out to see Jim Davidson, the former bass player with The Dead Things, a Lower Hutt R&B band.

We were out in Lower Hutt again later that day, contemplating one of the largest collections of New Zealand vinyl in existence. Colin Linwood, a post office linesman and vinyl freak, is a fanatic’s fanatic who wants a copy of every vinyl record released in New Zealand. Doesn’t matter what’s on the record. He has rooms full of them. The rest are stuffed into his garage. John named rare records and Colin was pulling them out, so excited he’s gibbering, his eyes full of barely controlled glee.

Wellington had one of the most vibrant 1960s and 1970s scenes in the country. A large baby boomer population and the need for dance bands in the city’s many isolated suburbs ensured that. It was also the political capital of New Zealand, which gave it a profile that its size didn’t necessarily warrant.

Rick White was the bass player with one of the city’s longest-lived 1960s groups, Tom Thumb. He lived on a high slope in one of the windy city’s tunnel and hill suburbs. White’s a good talker and listener and readily answered questions about Tom Thumb’s many line-up changes and obscure singles, three of which, ‘Got Love’, ‘You're Gonna Miss Me’ and ‘If I Were A Carpenter’ are classic New Zealand covers.

Rick’s good on all that, but excelled especially on the scene’s characters, both industry and creative, and its infrastructure of clubs, recording studios and record labels. It was a great way to finish up the trip although John being John, he can’t resist stopping in on a reluctant Charlie Horsham, the Dead Things singer, who was now a plumber in Masterton.

We arrived back in Auckland just after dark, where I was dropped off at Stu’s in Epsom, despite John insisting I stay for that night’s Nothing At All! show. I declined, needing some space. It took a week to settle back into my day job then it was into tape transcribing and yet more interviews.

We talked to Ray Columbus in the garden shed office behind his luxurious St Heliers house. I was a little awed by Ray. He had a star quality that most sixties-era musicians don’t and he was open, friendly and approachable. He had every record he ever played on in that shed and clear memories of them all.

We were there to find out about his time in the San Francisco area during the Summer of Love, where he recorded the psych-punk screamer, ‘Kick Me (I Think I'm Dreaming)’. It’s not a period he’d been asked about before and he quickly warmed to the subject. When John asked Ray point blank if he ever tried acid, Ray gives us an ambiguous reply in keeping with the era and we all laughed. Talking about sex and drugs in public required a different language back then.

I started writing Social End Product in early 1995. There were more interviews for stories on The Music Convention, who wrote the soundtrack for New Zealand's first surf movie, Children Of The Sun, filmed by Andy McAlpine, and a freaky piece of flower power psych, ‘Footprints On My Mind’.

We tracked The Human Instinct guitarist and songwriter Bill Ward to a farmlet just outside Katikati. He was now a brickie and calm with it. He had a good scrapbook and photo album and his old guitar and amp in the attic.

In Hamilton, Human Instinct bass player Frank Hay still had his 1960s buckskin-fringed jacket in a closet. The dark brown coat, similar to Neil Young’s in Buffalo Springfield, was stiff and still needed wearing in.

This is the first Human Instinct of renown. The provincial pop band, who took a punt on London and England, where they played extensively and recorded a handful of psych-era classics. Drummer Maurice Greer later returned with the second era Human Instinct, featuring Hendrix fan Billy TK, up front and take the name well into the 1970s.

When Social End Product appeared in August, John lined up an interview with Max Cryer on the Lindsay Perigo-helmed far right radio station, Radio Liberty. It seemed an odd choice at first. John has a perverse sense of humour, and an instinct for the offbeat, but there was some logic there. Max is a musicologist. He’s also New Zealand’s most released singer, as he quickly informed us, and a smart, sharp guy.

They played ‘Social End Product’, the engineer grooving away. He knows this song.

The wider media responded well to the magazine. Graham Reid wrote us up in New Zealand Herald as did John Dix in New Zealand Truth and I wrote a road story for Russell Baillie at Real Groove. The Press in Christchurch ran the Chants R&B story in its entirety in their weekend features section, when we’d only okayed an edited version.

We also tried telly. TV3 ran a semi-successful kooky late news piece, but on TVNZ, Paul Holmes passed because we were too “alternative”. When Wayne Mowat on National Radio sounded skeptical on air about the magazine’s appeal, John bit back, calmly asking Wayne about his period as singer in Dunedin 1960s R&B group The Dischords. Wayne struggled to recover after that. At 95bFM, Nick D’Angelo had even read the magazine, but the interview was shortened when John was late. “You should have arrived on time,” he cautioned.

Up on Ponsonby Road, my University of Waikato flatmate Megan Carter okayed a full window display at her magazine shop Magazzino. John got a professional window dresser in to dress it. By then, I was well into writing the second issue.

We caught up with John Williams at his mother’s house in West Auckland, where the Larry’s Rebels guitarist laid it all bare. It was one of the most revealing interviews we did. Williams was in his mid-teens when Larry’s Rebels hit big. He wasn’t a drug user. He was a brilliant player, a songwriter and an honest guy with a good memory. John caught up with Rebels drummer Nooky Stott and bass player Viv McCarthy, but Larry remained elusive.

John was out of control by then. EMI Records wanted four compilations from him – Bari and The Breakaways, The Librettos, The Avengers and The Pleazers – and he wanted four sleeve note histories from me. I didn’t sit in on any of the interviews for these. The tapes arrived in the mail or were picked up on my fortnightly trips to Auckland.

There was one good spinoff. Former Breakaway Midge Marsden was tutoring a Waikato Tech music course and needed someone to talk about the punk and post-punk era in New Zealand. It convinced me that was what I wanted to research and write about. I was already talking to Simon Kay about Mysterex when John canned Social End Product 2. Money was tight and the first issue sold slowly after an initial burst. He’d had a mentor in to run his eye over our endeavours and took the advice to not publish. Our working relationship was already crumbling under the pressure, so in the long haul it was a good thing.

In the short term, it was difficult. I sold the Unknown Blues story to The Southland Times, who ran it largely unchanged, and some of the others appeared as sleeve notes for House Of Nimrod and Chants R&B releases, but most remained unpublished, until Audioculture.