The shoegaze genre first emerged in the UK around the turn of the 1990s, with guitar sounds bent out of shape by effects pedals and liberal use of the whammy bar. It was such a specific sound that musicians down in New Zealand initially folded it into their existing approach rather than take it up whole-heartedly.

Since about 2005 there has been a steady revival of this sound, with a raft of local adherents. Meanwhile the term “dream pop” has been applied to groups who took a similar approach of having vocals buried in the mix, while keeping their music more ethereal and delicate. Local examples include internationally successful acts such as Yumi Zouma, Fazerdaze, and Salvia Palth.

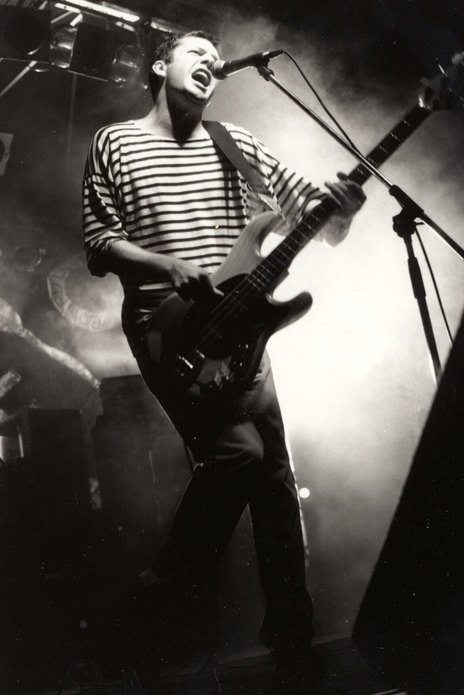

Fazerdaze playing a sold-out show at Mercury Lounge, New York. - Ben Howe

The starting point for shoegaze is often traced back to the Irish band My Bloody Valentine, whose 1991 album Loveless is held up as the quintessential release. Just prior to the band’s arrival in the late 80s, guitar playing had gone through a showy period with insanely fast solos and finger-tapping, which made heroes of the likes of Steve Vai and Joe Satriani. This made it even more striking when My Bloody Valentine coated their guitars in waves of effects, until they hardly sounded like guitars at all. Equally striking albums arrived by Ride (Nowhere, 1990), Lush (Gala, 1990), Curve (Doppelgänger, 1992) and Slowdive (Souvlaki, 1994).

This style of music became known, somewhat mockingly, as shoegaze, since the musicians often had so many effects pedals that they were always staring down at their feet. They took an equally obfuscating approach to their vocals, which were often mixed so low that you couldn’t hear a word they were saying – perhaps a response to the clean pop that filled the pop charts in the 1980s.

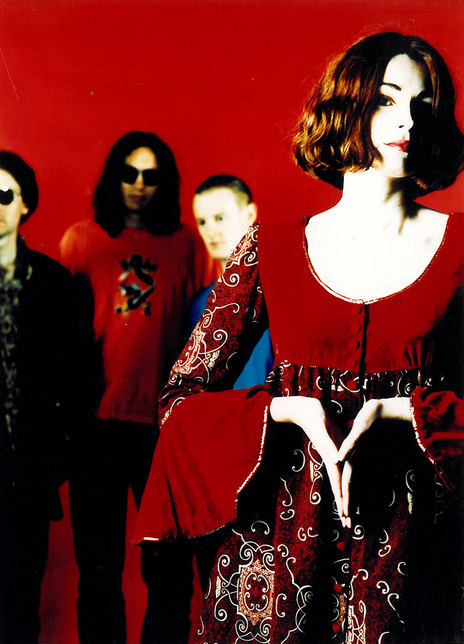

The term “dream pop” arrived slightly earlier and was originally an umbrella term that included shoegaze. The key act in this case was Cocteau Twins, whose singer Elizabeth Fraser sang in a made-up language of her own, using occasional words of English and Gaelic.

Dead Can Dance with Brendan Perry second from left and James Pinker on far right. - James Pinker Collection

The more ethereal end of goth music also seemed to focus on atmosphere more than vocal clarity. Dead Can Dance – the duo formed in Melbourne by Lisa Gerrard and and former Scavengers/ Marching Girls member Brendan Perry – was very influential in this respect. Drummer James Pinker from The Features, who also played with The Jesus and Mary Chain, appears on their 1982 debut album.

Dean Wareham (right) in Galaxie 500

In many ways, dream pop was a categorisation that became most useful in retrospect and in 2018 Pitchfork created a list of the Top 30 songs of the genre, with an introduction by Galaxie 500/Luna frontman Dean Wareham. He explained that “shoegaze bands are more of an assault, a wall of sound, while there is more empty space in dream pop.”

The sound reaches New Zealand

Dean Wareham was born in Wellington and left when he was seven years old, although his family continued to pay yearly visits until his mid-teens. He recalls buying The Clean’s ‘Tally Ho’ single when it first came out and his brother was friends with members of Beat Rhythm Fashion, a Wellington group whose gothy music was later promoted as proto-shoegaze when it was re-released in 2019 through Failsafe Records. Wareham’s band Galaxie 500 toured the UK with Straitjackets Fits in support and Justin Harwood from The Chills joined his subsequent band, Luna.

During the early years of Flying Nun, some of the label’s acts seemed to be on a parallel path to the dream pop and shoegaze bands overseas. The vocals in Bailterspace were increasingly overwhelmed by the waves of guitar, especially on the 1995 album Wammo. Peter Gutteridge’s Snapper had elements of this too, though with the drone of an organ added to the mix – their breakthrough single ‘Buddy’ is a prime example. It’s also possible to put many of the quieter songs of The Chills at the softer end of dream pop, especially with the almost-whispered singing style that Martin Phillipps often used.

Possibly the most striking case was Jean-Paul Sartre Experience, who began making music with the fragility of dream pop (‘Grey Parade’, ‘Transatlantic Love Song’), but eventually moved closer to shoegaze. Fuzzy guitars coat the near-whispered vocals on their 1993 album Bleeding Star. Singer Dave Yetton says their early sound was due to circumstance rather than having a specific aim in mind.

“JPS were doing very delicate music – what would now be called dream pop – right from our first EP came out. We didn’t intentionally try to make it like that. It was just a function of the fact that we didn’t know how to create big, distorted guitar sounds. We had Fender Stratocasters plugged straight into Roland Cube amps, because that’s what we had access to – mostly borrowed guitars and cheap amps. It ended up sounding really nice, especially when in a studio situation. They recorded really well, because the sounds were clean. A lot of people struggled back then because they were trying to capture big, distorted guitar sounds, which are hard to record. From our point of view, it was also a lack of knowledge because we didn’t know about pedals and what to do with them.”

David Yetton. - Photo by Murray Cammick

Yetton was intrigued by the arrival of shoegaze, but found it was a similar case of JPSE moving in parallel to what was happening overseas.

“We were definitely really keen on My Bloody Valentine and to a certain extent, other bands like Ride, but it’s not like we were rabid fans of that stuff. Though it did feel like it was in the same wheelhouse that we were operating in. It was just sort of in the air. For the same reason that those bands ended up going in that direction, perhaps we did too.”

Dolphin with Rob Mayes. - 95bFM Collection

It wasn’t Flying Nun, but Christchurch label Failsafe Records that ended up being most closely aligned with shoegaze in its early years. Label owner Rob Mayes recalls that his own bands were in sync with the sound, rather trying to ape it. Mayes originally created Failsafe to capture his hometown scene in the early 80s with a run of influential compilation albums. He perceived that his own band Dolphin might sound more atmospheric if the vocals were pulled back in the mix.

“I wasn’t trying to hide the vocals so much as blend them into a soundscape,” says Mayes, “and not make it about hearing well-articulated lyrics. Much of Dolphin’s lyrics were improvised abstract ideas. We would start out with music first and then Kev would improvise some mumbled emotive phrases over the top of that. We’d listen back to that and say, ‘It sounds like you’re saying this.’ We’d work up ideas from that to channel a lyrical idea to work in with the music. We started recording in 1987, so before I’d heard My Bloody Valentine’s first album Isn’t Anything, which came out in 1988. We knew and liked Hüsker Dü and their vocals are hardly up front in the mix so there was probably an influence there. We didn’t feel like we were making a lyrical statement, the words were secondary to the impact and emotion of the song.”

Mayes believes that the similarity between Dolphin’s sound and that of the early shoegaze bands was something that came about organically due to the time in which they were playing. For his part, he points to influences like Modern Eon, Danse Society and The Cure, who he saw live in 1980. Failsafe gradually began working with other bands with a similar sound, including 147swordfish and Mayes’ subsequent group Springloader.

The Malchicks. - Photo by Ian McRae, Jason Ennor collection

The Malchicks were an Auckland band on the Failsafe Records label, who more clearly picked up on elements of shoegaze, though singer-guitarist Matt Dalziel also cited bands like JPSE, Bailterspace, Dinosaur Jr, and Sonic Youth as being highly influential. He recalls that getting their desired sound took a lot of trial and error.

“In the days before websites, clips, and wiring diagrams of various rigs, we just had to apply ears, lateral thinking, and budget constraints, then focus on what we wanted to do. We spent ages getting the right tunings. There are some double dropped Ds, a Csus4 open tuning, and a D slack-key. That gave us plenty of chime and drone to build the songs around before we ever hit the studio. My main pedal sequence was Dunlop Wah, a phaser which might have been a Korean copy of a Boss, and a Boss Superfeedbacker. That was it. No delays, flangers, vibe or tremolo pedals, no extensive pedalboards … For texture we would often layer an acoustic 12-string under the main guitars. The rest was all in the playing, chord choices, harmonic combinations, and some unexpected time signatures. And, of course, the whammy bar …”

Failsafe also signed Cicada, whose guitarist Andrew Denton lists a range of influences. “We were together 1992-98 so influences came and went,” he says, “but there was Slint, Mogwai, Swervedriver, Sonic Youth, Fugazi, Bailterspace, Jesus Lizard, off the top of my head.”

This run of names gives a good sense of the mix of UK and US sounds that were being blended together by acts here in New Zealand. While Swervedriver were at the noisier end of the UK shoegaze scene (most notably on their 1991 album Raise), Slint were a US post-rock group whose vocals were similarly hard to decipher, and Mogwai are a Scottish post-punk group who did away with vocals entirely to create their epic guitar rock instrumentals.

In 1997, Dave Yetton returned with The Stereo Bus and found himself drawn back to the understated approach of early JPSE. The fuzz guitar remained on the singles ‘Shallow’ and ‘Don’t Open Your Eyes’. Yetton struggled to describe the sound he was going for.

“You could call it dream pop now, looking back at it, but I don’t think people referred to dream pop in those days,” he says. “I just called it sissy pop as a bit of a joke … Everyone in the band was the same – that sparse, dreamy style just came naturally to all of us. The whole grunge thing had happened and even though I really liked a lot of music that came out of that period, it just didn’t feel that it was unique or, at least, there were people doing it better than I could ever do it. Once again, part of it was the circumstances. Most of the songs were done in a little eight-track studio at RDU student radio station in Christchurch or on a four-track. A few were done in a studio, but not many. That small production style suited the songs I was writing.”

The Stereo Bus released two albums and Yetton followed up with a solo album before putting his music career on the back burner.