Stuart Pearce recounts some of the memorable moments of his more than four decades in the New Zealand music industry, including playing on and contributing to the arrangements of three New Zealand No.1 singles – ‘E Ipo’ by Prince Tui Teka, ‘Poi E’ by The Pātea Māori Club and ‘Tears On My Pillow’ by The Parker Project.

Rod Stewart & The Faces trash Auckland’s grand

“The first support gig Chapeaux played was Rod Stewart & The Faces at Western Springs [in January 1974]. Phil Warren asked me to organise a grand piano for the show, so I walked out of The Crypt and looked around ... Aha! Auckland Town Hall is just there, I will ask them. The Town Hall promptly said yes, they could organise the truck and everything, delivery date organised, and the pick-up afterwards. Sorted.

“So, we play our support set and The Faces play their epic show. As a teen I wasn’t shy, so in the lunch tent I had marched straight up to Ronnie [Wood] and Rod and invited them to our club gig the next night. They accepted. Phil Warren, club owner, was also promoter. At the finale of The Faces’ set, Ian McLagan, the piano player, pulls out a hammer to play the last song with. What a mess he made in a few seconds.

“This vandalism made the TV news, the Herald, the appalling behaviour, etc. The council was all in a bother over it. Rod and Ronnie and McLagan turn up at The Crypt, I meet them and take them straight into the band room backstage. Of course it’s only a pokey corridor in there. Phil comes tearing out and invites us all into his office. I get my first glimpse of this plush interior; drinks cabinet, pretty barmaids lounging around. In my naivety, I snubbed talking to McLagan as he had mutilated the piano.

“The Monday following, I got up early, fully expecting the police to phone me with some criminal offence to answer for. But this is a schoolboy mentality carry-over, where one kid messes up and all the boys are in strife. But no call came. Phil never once even mentioned this disaster to me. I guess The Faces paid the $8,000 bill that was reported.”

A bad night with Sonny Day

“Playing with one of Sonny Day’s bands about 1975, we get asked to open for Roxy Music in the Town Hall, so we foolishly learn three tricky new songs to be flash. The Roxy Music guys are fully decked out in 1950s-style mod gear, and it’s a highly stylish vibe, to say the least. What an impressive-looking band! Our little club band is feeling pretty drab.

“Just before we start our set someone backstage produces a doobie and our band is trolleyed in minutes. Going out onstage we are looking at Auckland’s Roxy crowd. Let's just say they were rather upmarket. Our first song fell to pieces as no one could remember it, the second song was quickly becoming a train wreck when the guitarist, who was fresh out of the slammer, had a moment of acute paranoia and disappeared behind his amp, kneeling down as if fixing something. He was in fact trying to hide, as he never came back out.

“We struggled through the next 30 minutes of miserable support gig. Sonny rescued the situation by reverting back to his normal set, but all I could see next to me was a backside poking out from behind a quad box, while not hearing a note of guitar. This must have looked bizarre to a packed Town Hall audience. Rock’n’roll handbook – on an auspicious occasion, don’t try to be something you are not.”

Street Talkin’ with crazy Kim Fowley

“Kim Fowley was an interesting encounter; a real character from LA, a mover and a shaker. He came down here to listen to bands and he basically told Tim Murdoch of WEA NZ that he was producing an album by Street Talk and that Tim would pay for it. Which he did.

“Kim wrote his lyrics in front of us sometimes. He would just splurge all this imagery onto a page, and Hammond Gamble would pack the lines in with his blues feel. I wasn’t in the band at this time, just a staffer [at Mandrill], but Kim says boldly, ‘Bruce Springsteen features piano, it’s going on here.’ At which point I was summoned from my job in the dubbing room and asked to play on 12 songs.

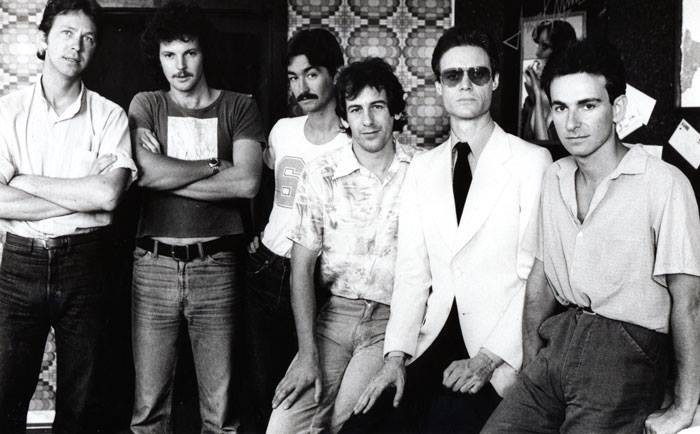

Kim Fowley with Street Talk at Mandrill Studio. Stuart Pearce is second from left.

“I know most of them were take one: one listen to scrawl a chart, one run through, Kim yells, ‘Great, next song!’ Then overdub some synth in the same haphazard fashion, and suddenly I find myself inflicted upon Street Talk as a band member. I think only Hammond liked the piano or myself.

“Later Jimmy Lawrie and I became good mates, flatting together. Mostly the other guys moaned about my presence. ‘Listen to Elvis Costello, his keyboard player [Steve Nieve] is good.’ Yeah, Okay, then. We played before Costello at Sweetwaters soon after. Er, piano player – not that good, mate. In fact, he’s as rough as guts.

“We all grew so fond of crazy Kim Fowley that we helped him pack his bags and clean up his room. I even think one of us nuggeted his shoes for him. He had given us a recording career with prospects.”

Prince Tui Teka: the man, the music, the legend

“I only did the one album with Tui, and it was called The Man, The Music, The Legend. And I think we recorded the whole album in two days. Because remember in those days, that when you get asked to play on a song with a band, someone’s doing a chart – at Mandrill it was usually me. If the band can’t play it within an hour, they don’t book you again. So we would put down a rhythm track every hour. So we lay down six tracks on a Saturday and five on a Sunday, so on the weekend the act would have their whole album laid down – guitar, bass, drums and keys.

“Then on Monday Tui came in to sing his album, and he sang the whole album. And then on the Tuesday I was doing overdubs, adding on more keyboard parts. Wednesday, Tui came back in and said he didn’t like his singing, and he sang the whole album again in one session, and that’s what’s on the record.”

The vamp on Coconut Rough’s ‘Sierra Leone’

“One Sunday night in 1983, I filled in for Murray McNabb with Jacqui Fitzgerald’s group, playing at Mainstreet Cabaret. I learnt Toto’s ‘Hold The Line’ for this, and the keyboard part was great to sit on. It’s a 12/8 rock’n’roll hammering job on the piano, but moves its triad voicings around just enough to inject extra melody into it.

The original Coconut Rough: Dennis Tuwhare, Stuart Pearce, Andrew McLennan, Paul Hewitt and Mark Bell

“The next morning, I went to a Coconut Rough rehearsal and Andrew McLennan had just written ‘Sierra Leone’. As the band worked up the tune, I came up with the idea for the vamp, inspired 100 percent by ‘Hold The Line’ and its detail.”

Recording ‘Poi E’: grass skirts and a LinnDrum

“Alastair Riddell owned a LinnDrum [drum machine] that we hired for $50, and Alastair operated the Linn in conjunction with Gordon Joll. Gordy says he pushed a couple of buttons, but I do know he punched in the perfect hi-hat pattern. Apart from the hat, the beat is only a quantised 1+3 boom-ka-boom-ka on repeat for five minutes. After I laid down the chord map from my chart, we nipped off the beat at the end, which went on too long. So, now the tempo and shape of it matched my chart perfectly, and it can be played.

“Next I played the bass with my Oberheim [synthesiser] in mono for fatness. The bass fill I only put there because I was concerned that there were no tom fills to cue the singers. Then Tama Renata played his rhythm guitar. Everything was one take so far because everybody was damn efficient. That’s what you had to be, and time was money. If you couldn’t produce the foundations for a whole album in two days, then someone else would be hired instead. So we had now been working 40 minutes and had completed drums, bass and guitar on this one song.

Poi E (Maui, 1984)

“The session took place from 5pm to 6pm. At 5:40, I popped up to the shop to get a sandwich, as I knew Tama would play guitar. Dalvanius yells out, ‘Don’t forget when you get back I want Space Invaders.’ ‘OK, Dal, I will only be five minutes.’ With a queue in the shop, I was gone 10 minutes. Then I ask Dal, ‘Is it time for the Space Invaders sound?’ Tama chimes in, ‘I’ve played it!’ He'd jumped onto my synth in my absence, found a nice patch and run his fingers up and down. The first time I heard the Space Invaders, it was No.1 on the telly. ‘So, we’ve finished, then?’ ‘Yes.’ At 6pm, the bus arrived from Pātea and the group swarmed into Mascot, probably 40 people.

“We were packing up to get out of their way, the track was playing and immediately some of the elders were saying, ‘What the hell is this? Bloody Michael Jackson?’ As I was leaving I heard Dal saying ‘Well, we young people are going to sing this song and you old people can sit out there and wait.’

“The general ambience of the track, Dalvanius recorded cleverly. Instead of hearing the ladies’ grass skirts randomly as worn by a kapa haka group, he had them in civvies. Then the skirt-rustling was recorded cleanly as an overdub by about eight people, swinging them in stereo. It added finesse doing it this way and reduced mayhem in the feel.

“The other thing that makes me chuckle is this was the first experience for most of us with a drum machine. These things cost about $5000 then, so Alastair had a serious bit of gear in its day. Relative to this figure, musicians were all paid $20 each for this session. This LinnDrum was the bomb. Being such a new thing, Alastair was sent off to the drum booth and patched in through the wall from the other side of the building.

“I had recently discovered the luxury of playing in the control room – no headphones, you hear yourself in situation through great speakers, etc. No one had yet realised to simply put the blinking drum machine in the control room too! After the beat was laid down I zipped around quickly to the drum booth to say hello to Alastair and Gordy, but they had already gone. I never once clapped eyes on either of them during the whole thing.”

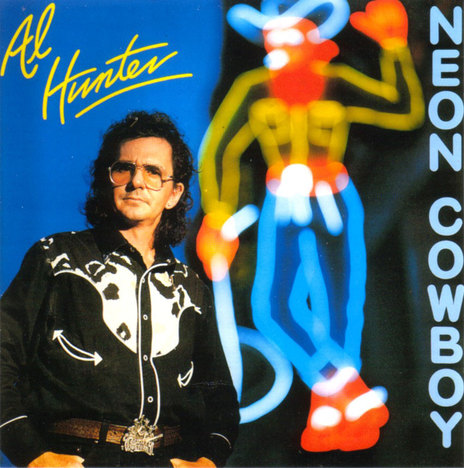

Producing Al Hunter’s Neon Cowboy

“Al [Hunter] had a budget for two songs, but because the latest thing in those days was a drum machine, it was like, ha, push the beat in here. The cost of making the record was cut down to about 10 percent, because you spent a fortune recording a good-sounding kit. And so I just said to Dave [Marett], ‘Look, I’ve only got three grand, but can we program up 10 tunes for Al?’ And he said, ‘Yeah, okay, but you do all the work and I’ll mix it.’ So I did all the work and he mixed it.

Al Hunter's 1987 album, Neon Cowboy.

“Yeah, I worked on that for three months. We had three grand and we got this great guitar player called Ken Francis and we had to pay him $600 a day, so we got him for three days. So, we spent $1,800 on this one guy. But the reason I did that was because we had a drum machine and we had a keyboard bass. I thought, ‘Well, at least we’re gonna have a real guitar player sort of cover up the fact.’ And so Ken played heaps of guitars.

“And then I think we spent $500 on Wayne Goodwin’s fiddle and $300 on the pedal-steel player Kenny Kitching. And then we got some backing singers in, but we ran out of money, and so we got Dave’s wife from upstairs to come and sing. She wasn’t very good. And then one night I was sitting in the studio on my own there and I thought, ‘Oh, fuck, I’ll sing this.’ So I finished off the BV’s with a lot of drop-ins. And Dave Dobbyn sang on a couple of tunes too, but he didn’t charge us anything, which was great. He just popped in one day and just sang two back-up vocals with Al. Like, in minutes; he was so good.”

DLT, hip-hop and Home Brew

“I was in Sydney fully set up in a Midi suite, and Murray Cammick began sending work for his Southside label – an idea he had in conjunction with Simon Lynch, keyboardist with Ardijah – for the next phase, the newly invented remix. While working on Upper Hutt Posse’s remixes I got to spend time with the group jamming ideas.

“The breakdancing in the ‘Poi E’ video had come to New Zealand via the movie Beat Street, but it would be several years before the term ‘hip-hop’ would enter popular culture. In 1989, DLT was immersed in this. He told me that the four pillars of hip-hop were breaking, bombing, beat making and rap.

“And how correct he was. Fifteen years later this exact process unfolded with my kids and their mates at home on Fourth Ave, Kingsland. With half of this house my home studio and the other half a breakdancing hangout for kids after school, breaking kept them occupied for several years. This came in tandem with bombing – just like DLT said it would – complete with council complaints and threats of fines.

“A few years later came the beat making, as they started poking their heads around the corner into my studio: ‘Can we make some beats?’ And as soon as beats are laid down to their satisfaction they are yelling, ‘Tom can rap!’ Tom Scott [Home Brew leader] had been entertaining his friends from a very young age with his lyrical twists and boyish shenanigans.

“I recorded him on a corporate track. Meanwhile, Tom’s father, bassist Peter Scott, is giving him spots appearing on his gigs downtown. Next thing Pete has organised a band for them and I muck in an old, broken-down Fender Rhodes in their shed to help get the show up and rolling.”

Filling in with Dragon

“My actual stint with Dragon came about because Alan Mansfield went touring with Robert Palmer. Kamahl’s son Rajan was on sampled BV’s, so he moved onto piano and I was brought in to operate sampled BV’s. I made a botch of this and Rajan made a botch of the piano. I said to Todd and Marc [Hunter], ‘Put me on piano tomorrow and put Raj back onto the sampler.’ Marc said, ‘Okay, but you’d better not fuck that up too!’ I stayed up all night and day and played a perfect gig for them on the second night. It was Todd who got me the Rockmelons tour after that. It’s a small network in Australia when you get involved.”

Recording The Parker Project’s ‘Tears On My Pillow’

“The Parker Project was a surprise. George Hubbard, who managed Upper Hutt Posse, had a drum machine. He and myself toddled around for a couple of days setting up a remake of ‘Tears On My Pillow’ for vocalist David Parker. Once again I played synth bass, only this time at George’s suggestion using only one chord when typically you would expect more. Just grind a bass right through a song without changing chords. It worked a treat and spent a week at No.1. This bass sound was the identical one that Simon Lynch had used on Ngaire’s ‘To Sir With Love’, which Simon kindly gave to me. At the last minute, engineer/producer/mixer Daniel Barnes decided it needed incidental spice on it, and he whacked on the Haines brothers – Nathan and Joel. A very nice touch.”

Setting up York Street Studio

“Mandrill closed and so Malcolm [Welsford] was like the chief engineer at Mandrill. So, Malcolm needed a new home base. Malcolm paired himself up with Martin Williams, who had the Last Laugh down in Vulcan Lane, and so they had the intent to join forces and open up their own studio. But of course Jaz Coleman [of Killing Joke] came into the picture then to make the trio.

“About 1990, Jaz Coleman had walked into Mandrill looking for a piano he could compose on; a huge talent, and a likeable Pom. Glyn [Tucker] let him use the piano in the smaller room, so he would play away there for hours when it wasn’t in use. One day, Jaz said he needed a room in the city, so I offered him the spare room at my home in Glen Eden.

“Jaz came into the picture and there you had the two engineer-drummers in town and Jaz, and so York Street just opened up. We all cleaned it out, scrubbed it, painted it, actually. We rolled our sleeves up to get that place open. This new studio needed a name. Touted at the time was Pump Studio, so I suggested York Street. It’s signposted, it’s in the directory, it has royalty and military connections, so they went with it.”

Shihad and “jazz”

“Probably the funniest thing was producing one song for a teenaged Shihad. The lads are down on the floor picking holes in their lyrics, and Tom Larkin casually makes the comment, ‘Make it more like jazz.’ Some scribbling goes on, then 10 minutes later I hear, ‘like jazz’ again, so I ask, ‘What do you mean like jazz?’ Tom says, ‘Oh, we really like this lyric writer Jaz Coleman, singer from Killing Joke. He’s mystical with his lyrics and political.’ I say to them, ‘He’s my flatmate.’ They ignore me. I repeat it and Jon Toogood says, ‘Yeah… okay.’

“I get Jaz on the phone, ‘Get down here, Jaz, there’s a band here who, A, knows you, and, B, loves your songs.’ ‘I’ll be down after five,’ says Jaz. So I tell the band boys, ‘Jaz is coming in after five.’ Jon just said, ‘Fuck off.’

“At 5:30, the Dark Lord, our pet name for Coleman, comes strutting down the corridor, jack-booted up and in his camouflage gear. The Shihad boys sat on the floor stunned while he lectured the fuck out of them. A match made in heaven. Jaz went on to produce their first full-length album Churn after two weeks’ preparation in my basement in Glen Eden. Inside this practice room would be the loudest sound I’ve ever heard. I can only compare it to jets preparing for take-off in your room.”

“Get a singer on a roll and you got ’em.”

“My fond memory of Glen Moffatt’s first CD was going through his schooldays songbook. In it was a string of songs he had written; most likely in the order he had written them too. It was a diary-type book. Glen played me all his songs from the front. After a dozen pages or so he played ‘Somewhere In New Zealand Tonight’. I couldn’t believe it. I think we had already sorted out most of his songs, but this composition was top quality.

“With Glen being a seasoned live singer who hadn’t recorded before, I decided to record his singing without him really noticing. I said, ‘Every night after we finish tracking the rhythm tracks, just sing once every song we have done so far.’ After three or four days of this, I was starting to tick off lead vocals as being finished. Get a singer on a roll and you got ’em.”

Latin piano: clean, tight and hip as hell

“I’m sure every musician goes through phases of getting sick of hearing themselves – your traits and limitations over and over again. Technology was one escape from this. You could try to be a player of a completely different instrument; strings, piccolo, etc. One massive freshener for me was discovering Latin music, firstly with Kantuta productions and then playing in Miguel Fuentes’ band Nativo. Piano is a tuned percussion instrument. It was only with Miguel and his percussion ensemble that the penny really dropped for me. Latin piano is clean, tight and hip as hell if you get good enough. I achieved the first two, not the latter. But learning some of the Latino disciplines helped in every area of music.”

Working with Gray Bartlett

“I have had a very long and productive association with Gray Bartlett all my musical life. Gray regularly needs keyboards for recording or shows, and I admire his relaxed approach to promoting. In his game you need balls of steel! Gray’s philosophy is a good one: tour 10 acts, break even on about six, make some money on two and lose a bit on two.

“But this kind of decision-making is something I would not enjoy. ‘How would Lenny Kravitz go in the Vector?’ ‘Jeez, Gray, can’t help you there.’ Sod that responsibility. From a keyboard seated safely at the back of a band somewhere, it’s highly unlikely I would lose $50,000 in one night! Much admiration.”

Hello Sailor’s Dave McArtney and Graham Brazier

“It’s not particularly loud onstage for keyboard players. The amps and drums are metres away, and if you are balancing your keyboards to a piano, they aren’t loud at all. The guitarist is usually blasting at a right angle to you, mostly hitting himself in the back of the legs. Dave McArtney insisted on having his amp at a diagonal so that Harry [Lyon] could hear him from the other side of the stage. So for about 25 years I carried a set of earplugs only for playing with Dave. Sorely missed, Hook, you loud bugger.

Dave McArtney and Stuart Pearce, 2007.

“Brazier was the funniest individual I have ever worked with, and that’s saying something as there are some hellishly amusing characters in this biz. For the entire decades of working with Braz, he insisted on introducing me by the utterly ridiculous name of Artemis. It must have meant something to him, but it made me feel like a pretentious wanker. Then he would endeavour to mess up my solo break, standing in front of me with his dick out, or sitting on my seat and pushing me off the other side, or going behind me and wrapping his arms tightly around my whole upper torso so I could hardly breathe. Flapping your arms like a seal does not make for good playing of piano. Love you, Braz.”