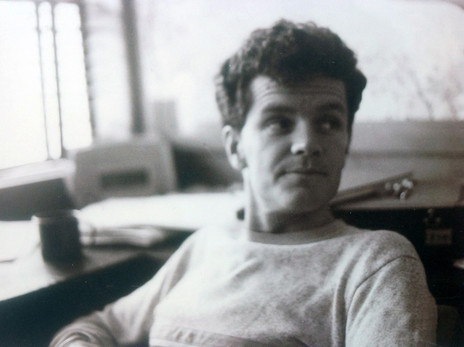

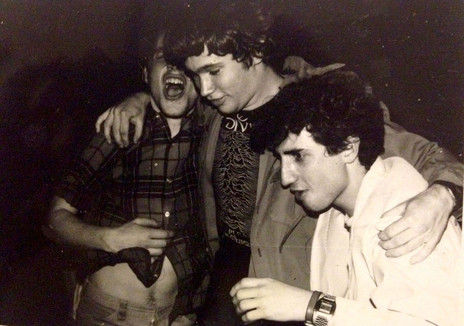

Terry King in the early 1980s

Run an eye over the production and recording credits for some of the most enduring independent music recorded in the Queen City in the first half of the 1980s, and you will often find the name Terry King.

The ongoing appeal of the fledgeling sounds that King engineered and sometimes produced at 45 Anzac Avenue in Auckland’s inner city can be seen in the recordings that have been reissued in the 2000s. Among them are Bill Direen’s first album, The Builders’ Beatin Hearts, the entire Bird Nest Roys catalogue, The Stones’ sole EP, Another Disc, Another Dollar (reissued as part of the Three Blind Mice compilation), plus a trio of early tracks on 2014’s Join The Car Crash Set compilation.

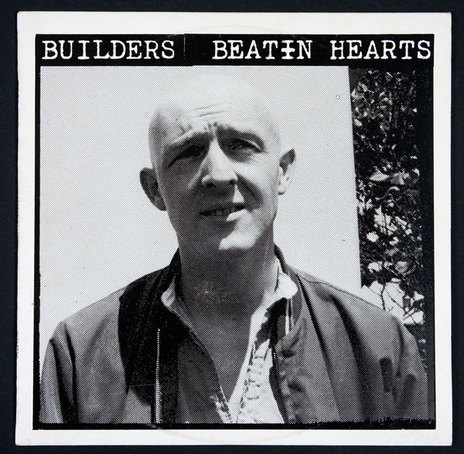

The Builders 1983 album Beatin Hearts, widely regarded as a landmark recording

Not that the appeal of the records escaped notice at the time. At least eight records engineered or produced by King made the New Zealand pop charts, and others quickly became cult favourites.

In the early 1980s, King’s Progressive Music Studio (often referred to as Progressive Studios) quickly established itself in an increasingly busy Auckland studio environment. The studio was known as a safe pair of hands for new groups making their first forays into recording for release.

After noise complaints chased them from their first site in Elliott Street in late 1981, King and his friends built new rehearsal studios on the second floor of an old multi-storey building on Anzac Ave, two blocks back from Waitemata Harbour.

The Anzac Avenue space became very busy. Any time of day and night, $25 got you a minimum of six hours in the fully sound-proofed practice room or one of the two less-baffled spaces. It was a small step from there to the eight-track DBX studio with 16-into-8 channel desk and 2-track mastering facility for “the ultimate in reproductive experiences.”

The Able Tasmans record at Progressive, 1989

Many a fledgeling group – among them The Narcs, The Mormons, Straight 8’s and Green Eggs & Ham – put down early demos at Progressive. The studio technician was John Kuipers, and part-time staff included Bernie Griffen, Richard Holden and Paul Gilbert. Griffen recalls, “Terry I were partners for nearly 10 years. When I first met him he was one of the most sought-after soundmen in Auckland. A rather droll character, we worked well together. Progressive Studios was the passion of half a dozen partners. They all had their interesting facets. But Terry was his own man. He was able to handle customers easily, and once we started recording, he was in his element.”

David Pinker of John, and Green Eggs & Ham's John Kuypers and Nick Hanson at Progressive Studios, 1981

Bill Direen says that King was like “an invisible Builder” during the Beatin Hearts sessions. “His choice of microphones, his suggestions for hardware and his treatment decisions were responsible for the very special quality of each of those releases, above all the quality of signature songs like ‘Do the Alligator’ and ‘The Cup’.

“We would drive up the country in cramped conditions, gigging and raising the angst levels about the new material, before landing at Progressive where Terry’s calm and friendly nature smoothed out all the worries. Sometimes he might suggest a backing singer, or a musician who might add some extra garnishment, but he never made me feel he was cooking the music. He listened – to understand what we might want to sound like – before quietly making technical decisions that presented it in a unique way.

“I was not surprised to hear that he came to be valued as one of the world's best sound engineers. He managed our material in a subtle and genteel way that understood where we were coming from. It was great to work with someone who believed in the music as he did.”

Early in 1983, Progressive set up camp behind the main stage at 1983’s Sweetwaters festival south of Auckland and handed out an open invitation to a belated Christmas party for those who’d used the studios in 1982.

Inside Progressive Studio in the mid-1980s

King had already engineered or mixed many ground-breaking recordings by mid-1984 when journalist Garth Cartwright – researching the busy Auckland studio scene for Metro – sat him down in Progressive’s “subterranean” confines. As well as Beatin Hearts (August 1982) and The Stones EP (December 1982), King was behind the desk on This Sporting Life’s In Limbo EP, Phantom Forth’s The Eepp, They Were Expendable’s Big Strain EP, Children’s Hour Flesh EP and Ya! Ya! Ya! single, The Chills’ ‘Pink Frost’, The Great Unwashed’s Singles and The Verlaines’ 10 O’Clock In The Afternoon EP. All were released on Flying Nun Records.

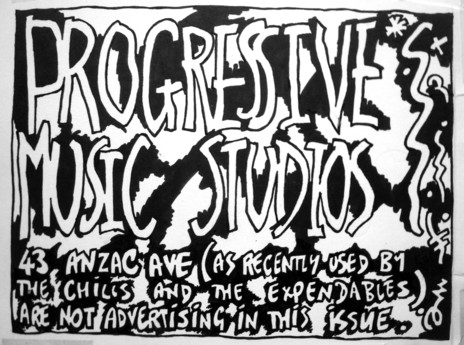

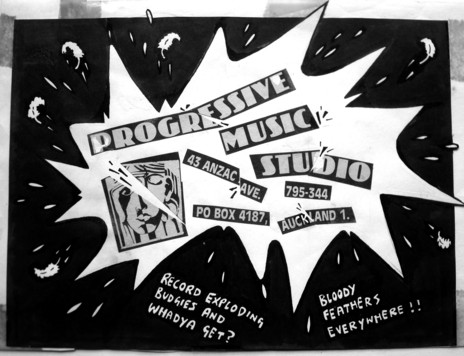

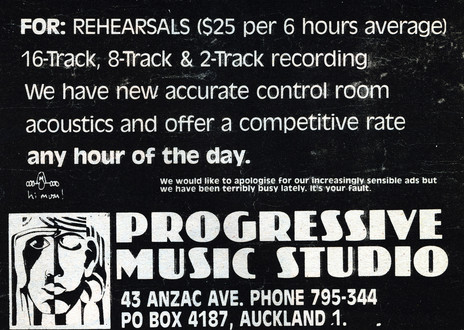

1980s advertisement for Progressive, with artwork by Chris Knox - Ian Dalziel collection

“We attract the younger, more adventurous musicians, the grassroots of the industry, people who are younger and less experienced,” said King. “These are the musicians who will around in five or 10 years.”

Progressive’s holistic and inclusive philosophy appealed to the younger groups. King was interested in the quality of the songs he helped capture on tape, taking a humble approach to communication and creative interaction. “We work with the band. We don’t force them to work with us.”

Terry King behind the desk at Progressive Studio, 1989

Progressive Music Studio was a music community-minded, non-profit endeavour, utilising PEP (Project Employment Programme) funding and talent in its establishment. as evidenced by the painted murals of music greats Robert Johnson, Elvis Presley, Billie Holiday and Jim Morrison on its walls. Terry King and engineer Tim Gummer also invested $25,000 of their own in the project.

Cartwright discerned a distinct studio sound and method there. “Blunt may be the correct term for Progressive’s sound,” he wrote. “It isn’t soft, pretty or dull. It possesses an edge to it, sometimes almost under-producing an artist so the musicians can produce a maelstrom of sound. At worst, it’s unlistenable, at best, it captures musicians breaking through rock’s established barriers. It is never, ever, cuddly.”

Which is an apt enough description for the spread of music recorded at Progressive by The Henchmen (We’ve Come To Play LP), Normal Ambition, Silent Decree (1983’s In Loving Memory tape), Vicious Circle, The Mormons, 8 Living Legs and YFC (Between Two Thieves EP). Other recordings at the studio were overseen by Graham Gash and Ivan Zagni – by acts such as The Economic Wizards, Car Crash Set and The Diehards – point to a broader catchment. But there is no doubt that rising groups from the still-potent and growing post-punk scene, including those from the South Island, found a comfortable home at Progressive.

1980s advertisement for Progressive, with artwork by Chris Knox - Ian Dalziel collection

That was partly down to the involvement of Doug Hood, who was often right there beside King, producing the new groups who had come to Auckland to record and play live shows at the Windsor Castle for Hood’s Double Bookings agency.

Hood first met King through Children's Hour, who were rehearsing at the studio. “It was pretty chaotic to start with, he was learning his way,” says Hood. “He was still building the studio, there were lots of issues to start with. The monitoring was through. It was all new and built on a shoestring. Terry was such a cool guy: a really nice person that people enjoyed being with.”

Progressive, being a roomy studio, was often rented by many bands as a rehearsal space “He probably earned more money through rehearsals than recording,” says Hood.

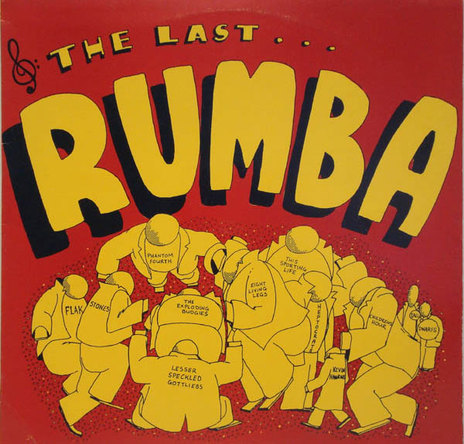

Outside of Progressive, in June 1983 Hood and King spent an entire day in the soon-to-close Rumba Bar, recording a whole swag of current indie bands live for Flying Nun’s The Last Rumba compilation. For Propeller Records, King had previously harnessed another live album, No Tag’s roaring punk on Can We Get Away With It?.

The Last Rumba, a live album released by Flying Nun in 1983, recorded by Doug Hood and Terry King

At 1983’s Auckland Battle of the Bands, six out of eight semi-finalists rehearsed at Progressive with the other two acts being mixed by the studio’s engineers. Three songs by Mark, Sid & James, 8 Living Legs and Car Crash Set on 1983’s We’ll Do Our Best compilation on Propeller Records were first captured at Progressive.

In November 1983, Progressive estimated the average price paid for a song released on record that had been recorded in the studio was $80.24.

A July 1984 Rip It Up advertisement introduced Progressive Promotions, which promised information and advice for bands, an extension of earlier intent, that included plans for video, promotional services, dark room space and practical courses in sound engineering.

Progressive Music Studio, which would provide a living wage for King, expanded its 8-track studio to a one-inch TEAC 16-track in mid-1984. Steve Garden and Tim Gummer’s Basement Tapes, previously a studio beneath a second-hand shop in Mount Eden, had already been absorbed into the Progressive setup with Garden becoming especially active in production from mid-1984, as the studio’s first engineer. Garden recalls that King was “optimistic and enthusiastic, a bit of an adrenaline junkie, but most of all he loved people – especially those who were good at something. He celebrated talent. He wasn’t threatened by it, in fact he took pride in making it possible for others to express the qualities they had.”

There was “a new consciousness and attitude” now present, one of the studio’s regular ads in Rip It Up proclaimed, that “ushered in a new era for the studio.”

Flying Nun Records-released groups remained regular Progressive customers well into the mid-1980s. Jay Clarkson’s The Expendables recorded Between Two Gears EP there, with Clarkson returning for her first solo album. “He’s a good engineer to work with, not pushy, but he gives good suggestions and knows when to knuckle down when you’re farting around. It’s a really good atmosphere,” she told Rip It Up.

Jay Clarkson

Recording with King at Progressive in 1985 was “invaluable”, says Clarkson in 2017. “He came up with the plan of me recording a solo album, and the way this would work was whenever he had down time he would come and pick me up and we would work on the album. In other words, I got to record an album for free.

“One of his reasons for this project was that he had become a little frustrated by bands tending to have very small budgets and having to rush things. Terry was keen to experiment more himself with the recording process. I liked his plan and actually moved from Christchurch to Auckland to see it through to fruition.” The result was a Jay Clarkson solo album, released on Flying Nun on vinyl only, though the label included many of the tracks later appeared on her CD compilation Packet.

“Terry was really easy to work with, a friendly and very focused engineer,” says Clarkson. “He cruised with the musician, but he also would come up with little suggestions that often would be the icing on the cake, as it were. And that huge reverb plate behind the wall in the control room was brilliant!”

Graeme Humphreys recording at Progressive Studios, 1989 - Graeme Hill collection

The Able Tasmans’ first EP Tired Sun, Goblin Mix’s self-titled EP, Not Really Anything’s Watched A World EP, The Chills’ Lost EP and The Exploding Budgies’ ‘Kenneth Anger’ were all recorded at Progressive as was The Builders’ Conch3 LP. Terry Moore produced The Alpaca Brothers’ Legless EP there.

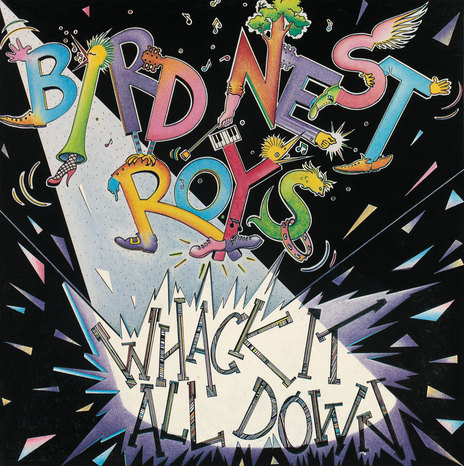

Bird Nest Roys became the Flying Nun group Terry King became most associated with, producing and engineering two out of three of their released records, engineering the other, and mixing the West Auckland six-piece live shows.

It was an experience Rip It Up got down in 1986, when staff writer Russell Brown caught a lift to New Plymouth for Bird Nest Roys’ weekend run at Ngamotu Tavern. “The footpath is strewn with bags, beddings and musical paraphernalia and the poor working stiffs have to pick their way gingerly around the pieces as they go wherever they’re going at 9am on Friday,” observed Brown.

“Camp mother/soundman Terry King stands by the side door of the van coolly running an eye over the personal debris before him and wondering how he’s going to fit it into the vehicle. Even more of a scenario is the fact that (count ’em) nine young people have to fit into the van along with all these amps, drums, guitars, mike stands and all ...

“As a van packer, Terry proves to make a good sound engineer and his lounge has to be substantially remodelled before it’s even fit for human habitation.”

The touring party encountered a slew of problems, including an eager cast of mushroom-town locals and a thinly attended first night. The more-populated second night saw Goblin Mix’s Alf Danielson and David Mitchell play a noisy, drunken support slot that drove King outside. There’s a difference between shambling and shambolic.

Whack It Down, Bird Nest Roys' 1985 debut EP

Bird Nest Roys enjoyed a reasonable run in New Zealand’s pop chart in January and February 1986, when their patchy, poorly pressed first EP, Whack It All Down, lingered for four weeks, peaking at No.20. ‘Jaffa Boy’, the warm and joyous follow-up single – one of Flying Nun’s best – gave a better representation of the band’s strengths in December of that year. The self-titled album that followed in May 1987 had its moments as well.

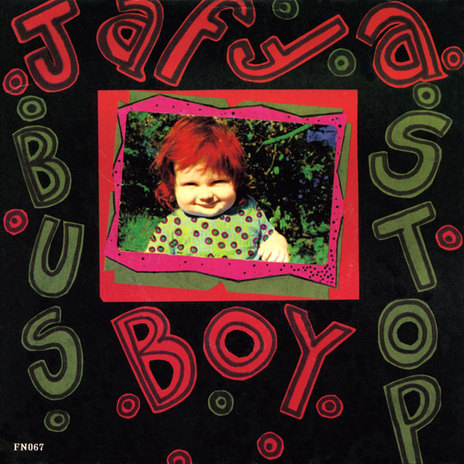

The Bird Nest Roys' 1986 single 'Jaffa Boy', produced by Terry King

In 1986, Progressive acquired a nine-foot Bechstein grand piano, and the recordings just kept coming. Bfm’s Outnumbered By Sheep compilation, released in February 1986, introduced Children’s Hour’s ‘Creeping Flesh’ (the only song recorded for a prospective LP in 1984), The Pterodactyls’ ‘Every Time It Rains’, Bird Nest Roys’ ‘Who Is The Silliest Rossi?’, The Expendables’ ‘Liberal Cad’ and Kim Blackburn’s ‘Oceania’.

All were recorded at Progressive. So to were Nick Smith’s Flanker EP, Snakes’ Snakes EP, Jean-Paul Sartre Experience’s sublime ‘Grey Parade’ with two other songs from their Love Songs LP, and Ebony Sye’s If You Want To Be King.

King seemed to bow out of hands-on recording for new groups after 1986, but Progressive Music Studio continued to be used for recording and mixing by Look Blue Go Purple, Steve Apirana and From Scratch, alongside lots of Steve Garden produced work. King’s association with the Bird Nest Roys resumed in the early 1990s when he helped record The Tufnels, a new group formed by key BNR members, for release on their Lurid LP in 1994.

From the mid-1990s King increasingly spent working in sound recording for film and television. Among them were the Topp Twins’ documentary Untouchable Girls, and many shows for Eyeworks (now Warners), including The Block and The Great Food Race. He also worked for smaller production companies such as KM Media, who made Café Secrets, New Zealand with Nadia Lim, Best of New Zealand with Nick Honeyman and the children’s series Let’s Get Inventin’. He regularly recorded the sound for Jono and Ben, and occasionally for Country Calendar.

Terry King passed away on 11 July 2017.