AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Dave Roper

aka D-Rave

The duties performed while delivering show and artist to venue and host city are often not so clear cut however, as longstanding music promoter Dave Roper found while carrying a passed out hip hop superstar between breakfast at Denny’s and said rapper’s hotel room.

The scenario went something like this. Well-known rapper performs sell out show. Later in the night (more accurately the next morning) rapper has beef with Denny’s waitress over her insistence the customer must pay before food is delivered. Dave diffuses the situation. Rapper happily eats breakfast. But then rapper’s straight vodka diet at the show after party catches up with him and he falls asleep at the table. Dave evaluates options, before slinging rapper over his shoulder and setting out into the street in order to put rapper in his hotel room before the next flight and show.

Though this story reads like an excerpt from a Los Angeles-based music industry memoir, the incident in question happened in Auckland, New Zealand in 2009 – one of presumably many of the stranger stories that comprise Dave’s nearly 20-year career as a New Zealand music promoter, club owner, artist manager, record label head, and deejay.

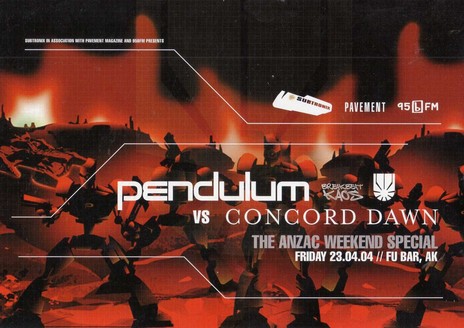

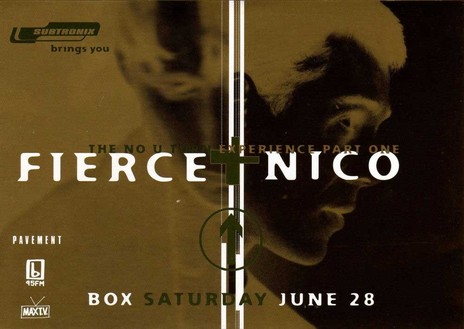

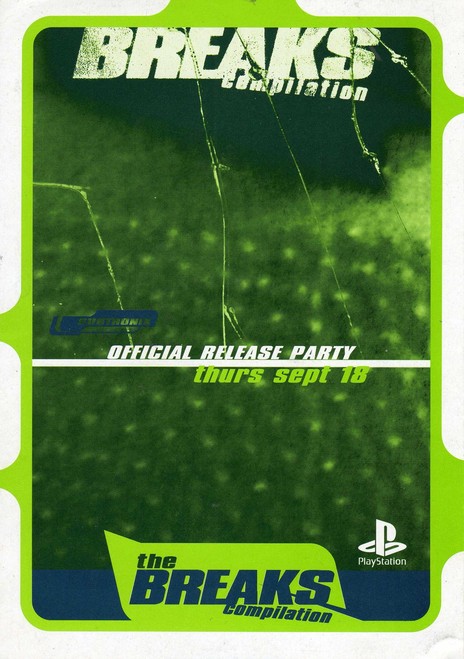

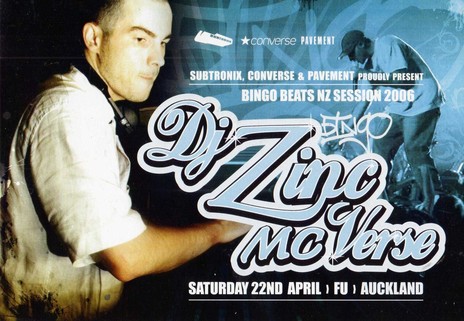

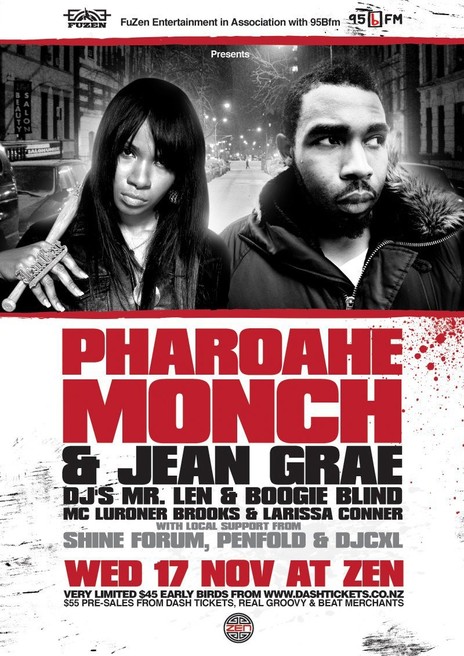

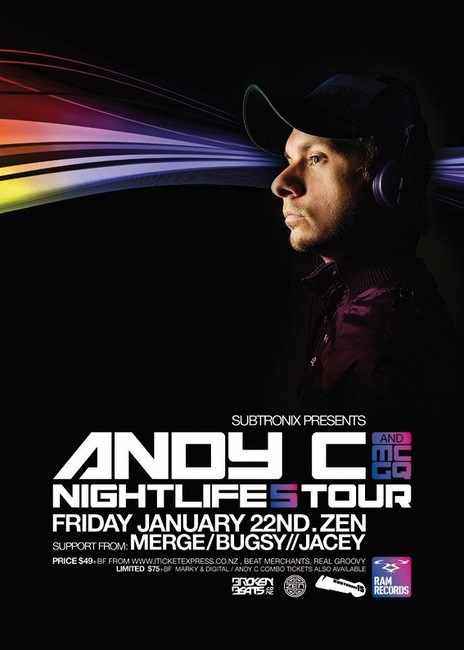

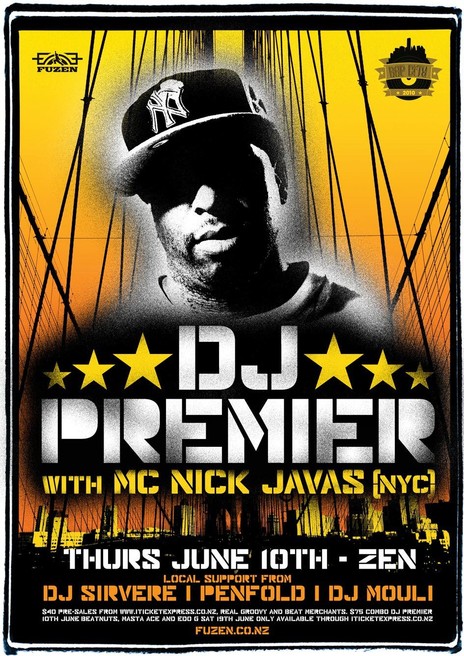

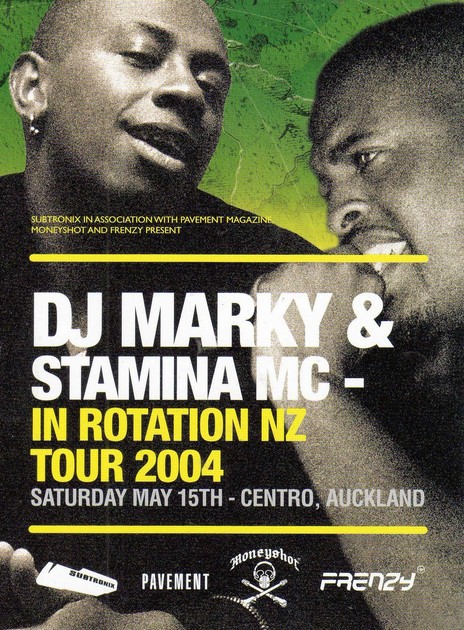

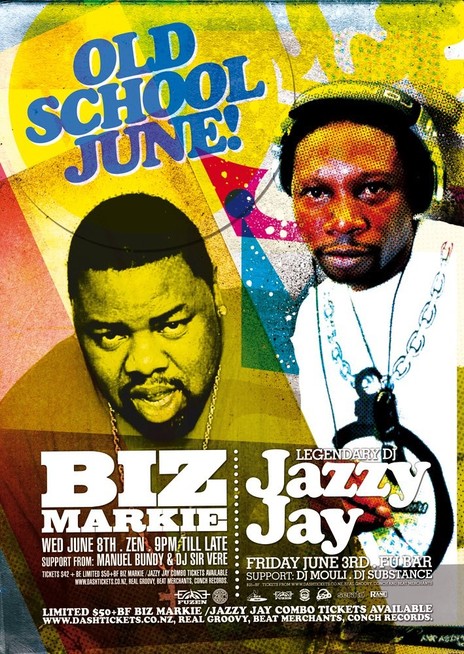

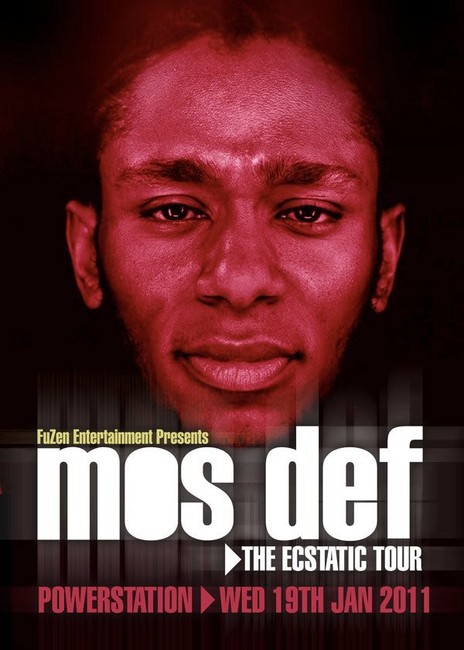

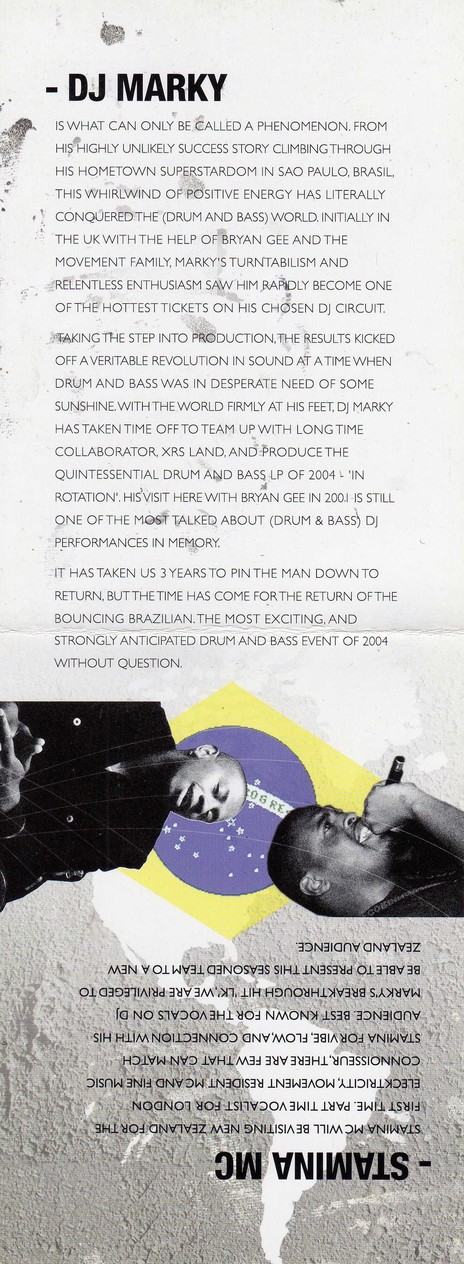

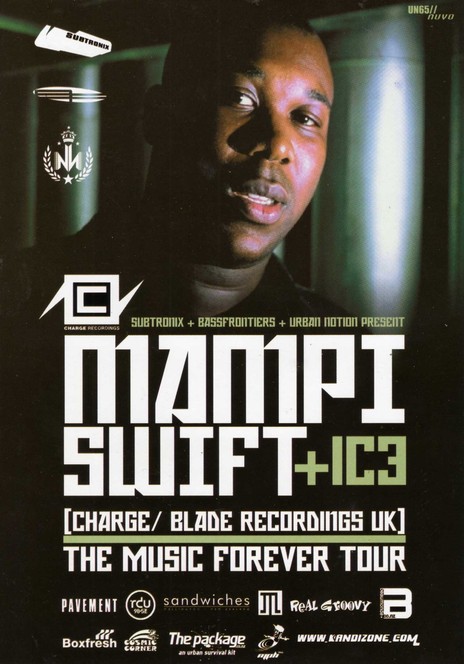

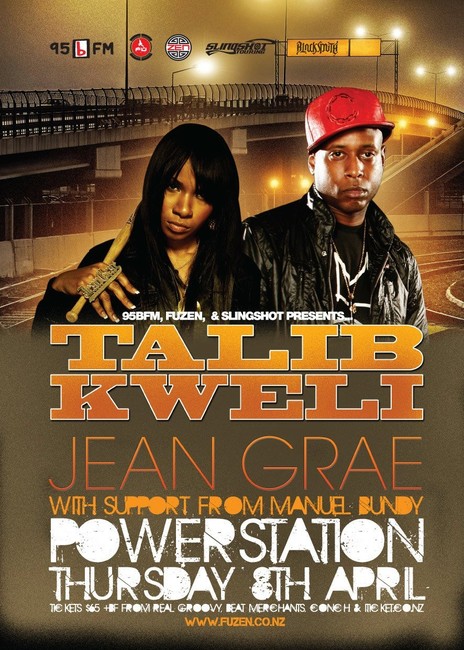

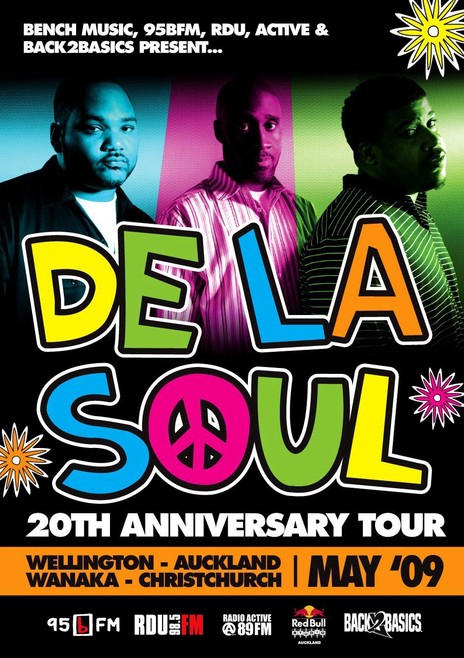

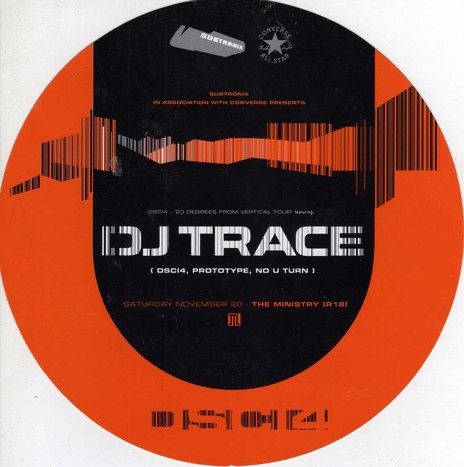

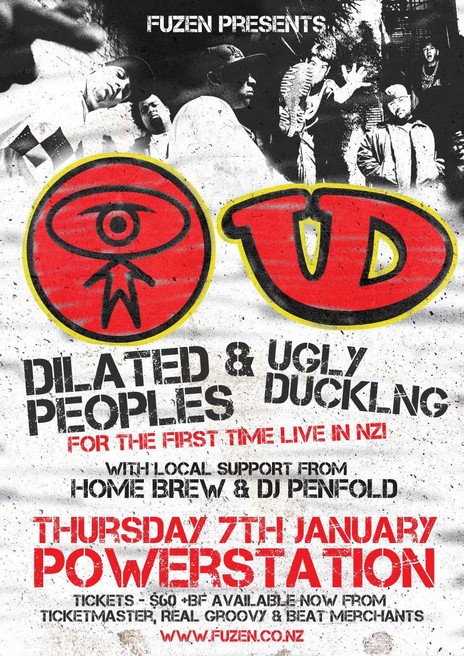

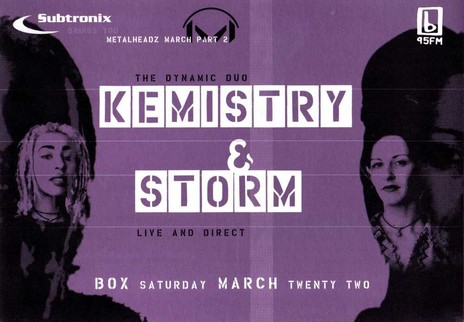

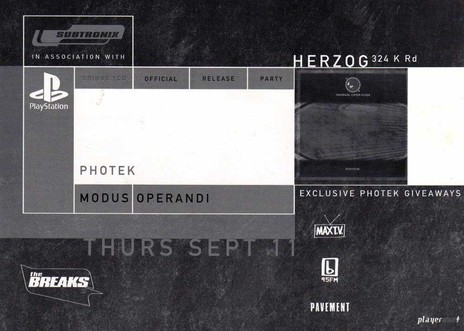

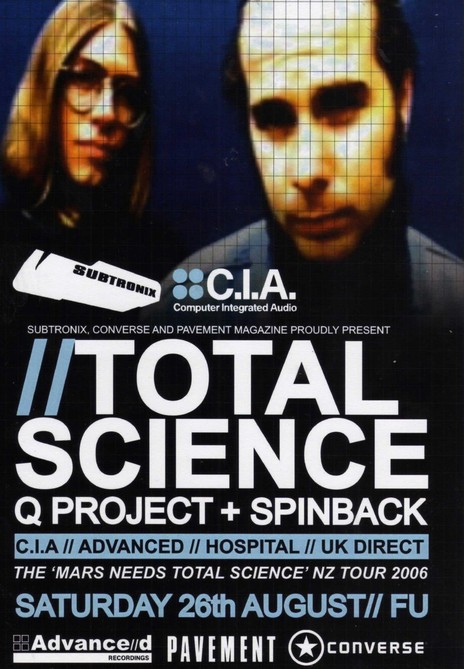

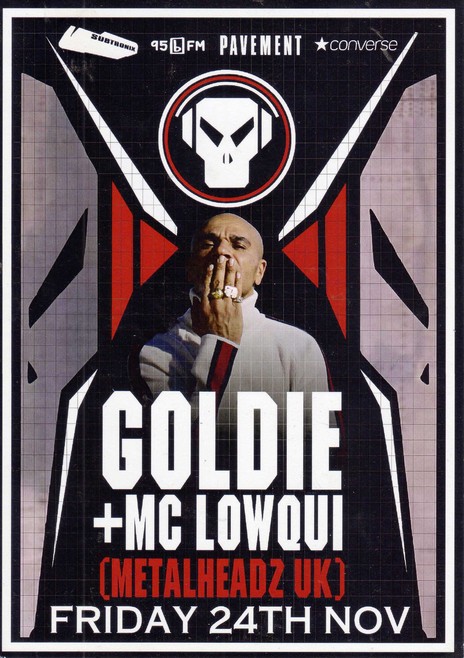

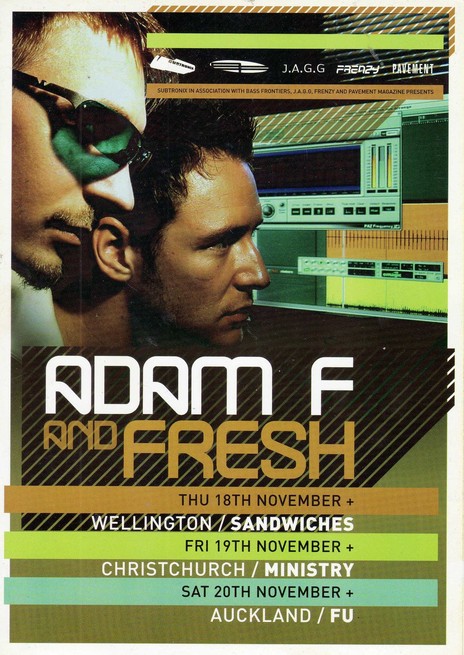

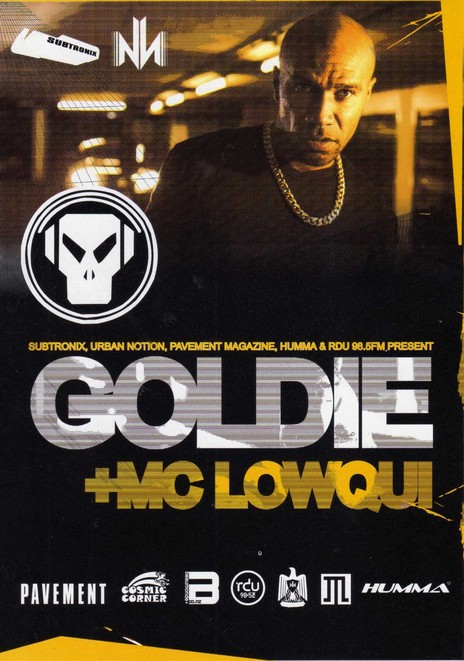

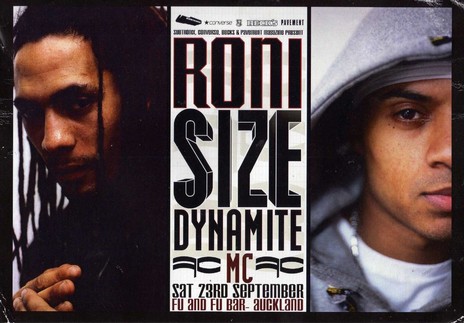

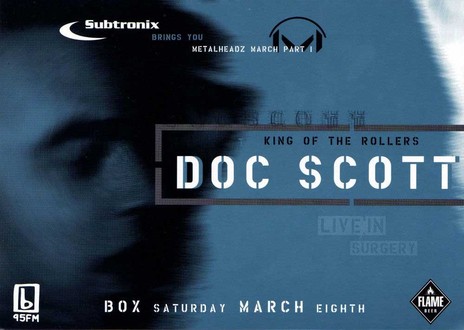

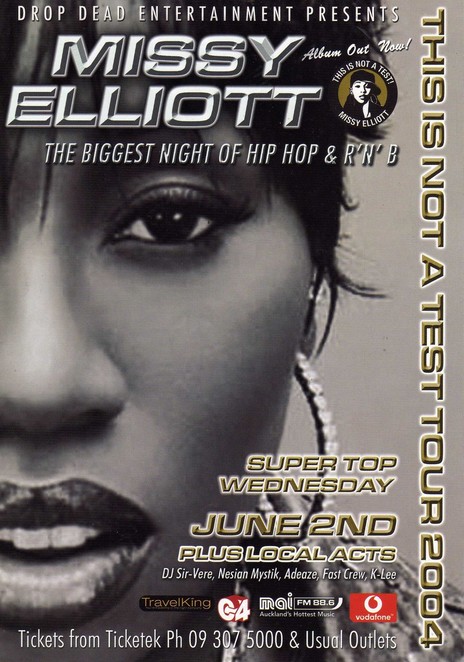

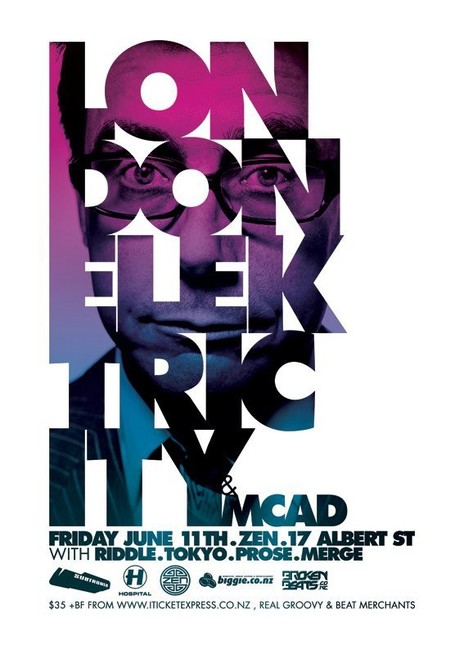

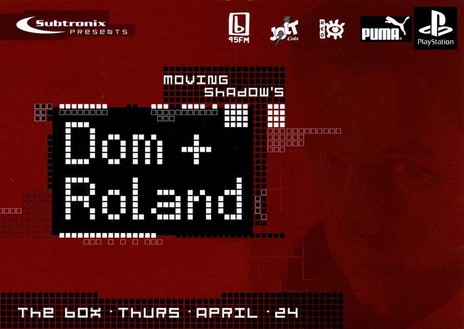

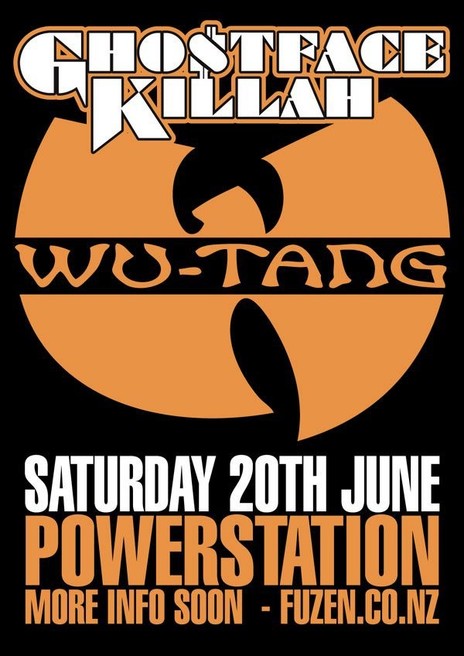

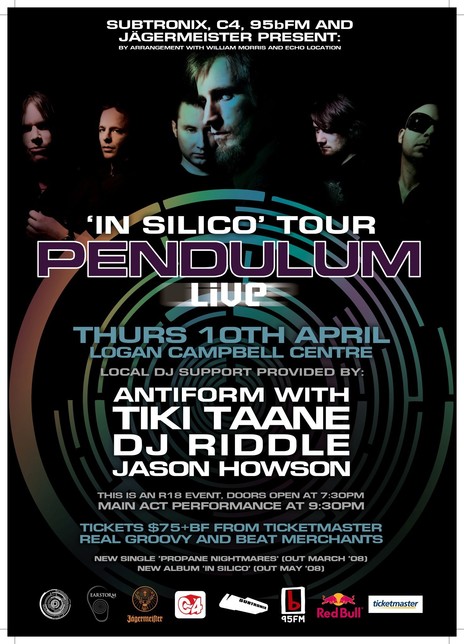

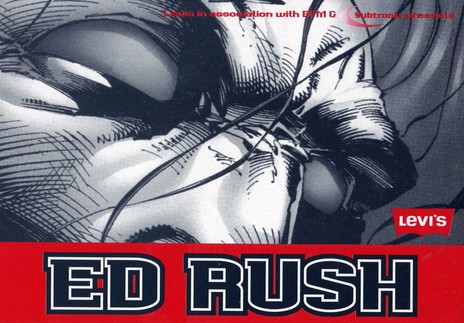

Following two formative trips to the UK as a teenager – where he witnessed the then burgeoning rave culture since referred to as the Second Summer of Love – Dave Roper was the founder of the seminal drum and bass promotion company Subtronix. Since then Dave has promoted acts and events in New Zealand, including Method Man, Chase and Status, Mos Def, Missy Elliott, Bone Thugs n Harmony, Cypress Hill, Anthrax, Suicidal Tendencies, Infectious Grooves, Noisia, GZA, Talib Kweli, Roots Manuva, Roni Size, Busta Rhymes, Pharoahe Monch, Ghostface Killah, Raekwon, DJ Premier, The Pharcyde, Chali 2na, Goldie, Andy C, Dilated Peoples, Mala, Richie Hawtin, DJ Zinc, Grooverider, Bad Company, DJ Trace, London Elektricity , LTJ Bukem & MC Conrad, Calyx & Teebee, Blackalicious, Digital, Dj Die, Dom and Roland, Logistics, Bryan G, PFM, DJ Hype, Randall, DJ Fresh, Will.I.Am, Kemistry and Storm, and Photek.

Alongside running Subtronix, which operated from 1996 to 2014, Dave was a programming consultant for The Big Day Out from 1999 to 2004, co-owned Fu Bar from 2001 to 2011, Zen nightclub from 2007 to 2011 (also booking international acts for both venues), co-managed local acts Fast Crew, Misfits of Science, and Timmy Schumacher, wrote for Real Groove and RipItUp magazines, as well as being a regular contributor to 95bFM’s Rock n Roll Wire radio show from 1998 to 2003. Dave also co-founded and executed the first two Northern Bass music festival events in 2011 and 2012.

Over a Cuba Street brunch, Dave reflects on the social and cultural environment of late 1980s New Zealand, as well as his trips to the UK around this time, both factors that would eventually led to him promoting music events not long after.

“I didn’t get rock. It stood for everything I hated. I didn’t really feel like I fit into the suburbs of Auckland. Which was basically drink, vomit, prove that you’re hard … play rugby. I was the guy from England with the slight accent who played soccer, or football as it should be called. I was also into electronic music, new wave and the like. Howick is a very middle class white place, and even in my college days I was hanging out with one of the few Māoris in the school … and a black American who happened to find himself in New Zealand! New Zealand in a wider sense was restricted in a lot of ways, not so far from the days of Muldoon when it was difficult to even import a record. All you could get in the cafes was filtered coffee and lamingtons.

“In 1988 during the break between high school and uni I took a trip to London during what they now call the Second Summer of Love. My cousin was a huge house maniac and took me to clubs. I was only seventeen, underage. I was amazed at how friendly everyone was, and excited by this new fresh sound I heard.”

It was Dave’s second trip to London in 1994 that solidified his eventual career path, a holiday which also provided one of the catalysts for New Zealand’s now long relationship with the originally black British sound of drum and bass. Though Andy Vann’s early parties at Auckland’s Powerstation, Grant Kearney and Sam Hill’s The Brain raves, as well as the culture at Box nightclub were sating some of Dave’s appetite for what he had experienced in London on the first trip a few years earlier, a stand-alone jungle and drum and bass scene had not yet established itself locally in any meaningful way.

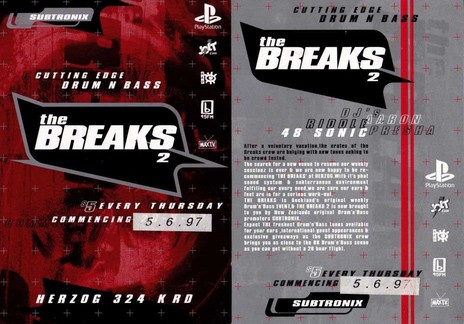

Dave remembers, “I got to London and my cousin said ‘I know where you should go; Black Market Records’. So I went there and that was where all the jungle and drum and bass music was, all the test pressings were coming in, you know … Ray Keith would be there, Nicky Blackmarket was there. I was just amazed by this new jungle sound – Suburban Base and Lucky Spin [labels] – that’s when I bought a ton of records. And I came back with stuff no one had, and I was like ‘I want to DJ’. So with the help of Grant Kearney and Sam Hill who gave me my first gigs, I started playing out. Then I started collaborating with other drum and bass DJs like 48 Sonic, Aaron, and Riddle, who were building their own collections of the music. So there was enough of us to form our own night.”

The rest, as they say, is Davestory. “So that’s when I started off doing the first jungle-only parties at Bob’s Bar in the DeBrett complex, and then also I did some parties called Jungle Soundclash with Andy Vann up at Poppa Jacks [now Cassette Nine]. After that I joined up with Andy Pickering and Omni [Dean Benfell] to form Subtronix, and we started to bring out the first internationals, Grooverider, Ed Rush, Zinc and all that … and then Dean went his own way and Andy ended up with Remix [magazine], leaving me with Subtronix. Then I met Presha [Geoff Wright], and then that’s when things really got started. Geoff had The Breaks at Calibre, a completely separate entity, and then we got talking and amalgamated. Then we re-launched The Breaks at Herzog [in Karangahape Rd], which to me was the ultimate glory days. But then the Box was great too with the internationals. Those were the golden years really, 1997 to the early 2000s. Every musical scene at its beginnings is at its best, and that was when drum and bass was really clicking, you know the No U-Turn sound, that kinda techy sound. We created this brand and people would trust us, even if they hadn’t heard of the artist, they trust that what we were doing and who we were hosting would be a good night out.”

Few international DJs toured to New Zealand until the mid-1990s, and the Subtronix collective played a key role in raising the profile and productivity of not only the local drum and bass scene, but dance music culture in general.

For those unaware, few international DJs toured to New Zealand until the mid-1990s, and the Subtronix collective played a key role in raising the profile and productivity of not only the local drum and bass scene, but dance music culture in general. Dave reflects, “It was a passion rather than a money thing. It was always about… New Zealand culture if you can remember back then was vastly different to now. It was so rock-oriented and you were mocked for having different tastes… it was about trying to push something a bit different. Me and Geoff made sure everything we did was the best we could do. Finding the best local DJs to support the touring act. Getting the best graphic designers, the best imagery. We’d spend a tonne on printing techniques; metallic inks, embossing … we were trying to be at the top, the point of the arrowhead. Back then with metal plates for printing we’d pay two or three grand just for flyers, whereas now …”

Dave comparing “now” to “then” does not stop at printing techniques. Hearing him reflect on nearly two decades of promoting electronic music and rave culture reveals some concern with a phenomenon that he feels has been appropriated by people with different interests and motivations than those involved in the past. However, far from presenting as someone with an axe to grind, Dave’s thoughts appear to hark back to his original experiences during those early visits to the UK, and the accompanying ethos he has attached to promoting and running music events since.

“The rave and club scene here, it used to be like Cheers. Always friendly faces, good conversation. People who were different than you but had certain similarities. It was just a great place to be at that time. It’s not like that now. To me, the difference is the mainstream came in and basically appropriated it, and electronic dance music, or EDM, is nothing to do with what we had. We started our thing to show we were not afraid to have different tastes, to be able to express being different from the mainstream.

“People in New Zealand seemed puritanical about, scared even, of being different. You were picked on. But more and more people went ‘fuck it’, I’m not a rugby head, I’m not a bigot’, and I think there were more and more young people who went ‘no, we’re quite happy to be different’, and took part in creating something new and something fresh. There was a place and a time, a zeitgeist. Like the punk era, you can’t replicate that, and there’s a reason you can’t replicate that. The politics of the day, the culture of the day. The rave era in New Zealand … people cottoning on to what was going on overseas. People wanting to create that. Even being there, everyone made it. It was a time immediately following rapid change in New Zealand, after the Springbok Tour, Rogernomics, and people being thrown out of jobs … there had been turmoil.”

He continues, “You look at the modern scene, like the EDM thing. Where there used to be etiquette … you didn’t get in other people’s way, you weren’t forceful. You were polite. You were there to dance and have a good time because the world outside was harsh, to come together and create something. But now bloke culture has permeated it, shredding for R&V and the like. But then New Zealand culture has changed in general though. It’s more celebrity and image driven. Especially in Auckland. We’ve become cheesier. We’ve become more hyper-capitalist and hyper commercial. Our media is flakier. The worshipping of superficiality has become far more commonplace, and this reflects itself in what people do for entertainment.

“Then people start talking about the underground these days. How can anything be underground if it’s Instagrammed, Facebooked, and Tweeted? There’s no underground. There’s no mystery. We got away with a lot of stuff, and there was a lot of excitement about what we did because of the mystery factor. Now everything is done for show and likes. You NEVER back in the day had pictures of the DJs as stars on flyers. There was a name in print, and it was not about glorifying the DJ and turning them into a rock star. Some of that early culture was a reaction against strutting rock gods … it’s funny … look what’s happened over time.”

Looking at what’s happened over time through a different lens, Dave’s music business arm has extended outside of one-off rave events to co-owning and running Auckland’s now defunct Fu Bar for a decade, the accompanying nightclub Zen (which operated for half of this period), as well as promoting large-scale predominantly hip hop events throughout New Zealand.

Then there was establishing and implementing the programming and logistics for large-scale music festival Northern Bass before he left the production team in 2013. These are ventures not sold easily in a mainstream market, rather outlets for more esoteric artists and audiences.

Working in this environment, and in a wider industry often known for people coming and going, Dave reflects on successfully navigating a career spanning two decades. “I think you need to check your ego, and stay within the realms of what’s feasible. Some people have a couple of years of success, a really good run, sell out show after sell out show. Then after a while they start getting in their head that they are brilliant. So they start taking bigger risks and bigger risks and bigger risks, and, um … hubris … hubris is the biggest thing you’ve got to be careful of. There’s a lot of yes men around promoters, and you’ve got to be careful. Then a lot of people let it get to their heads in a big way. Like the have a good model and they do the right kind of shows, but then they start going outside of that model. Like the guy who is regularly selling out 800 to 1000 capacity venues then suddenly he fancies himself as a mega promoter and just overstretches and he’s all over in that instance. You’ve got to know when to stand your ground, know your territory, not try to reach out into areas you do not know, and not thinking that you know it all. I think anyone could put on a few parties and do quite well, but maintaining it in the long-term is another story …”

Indeed it is. Presumably there are a number of stories no doubt worthy of a book one day, though aside from breakfast at Denny’s, Dave remains respectfully taciturn about some of the weirder and more wonderful moments of a career bringing music to the people. Reflecting on some of the highlights over the years, Dave seems lost for words. “Oh man there’s been so many occasions. When you’re on stage and you get the best of both worlds. You get to see the artist looking out to that crowd feeling the energy coming to them and then vice-versa you are watching the show like everyone else and get the energy off that. Sometimes things you don’t even expect … like when I ran the last Suicidal Tendencies show here, just the electricity running through the venue and the room, with the music, with the crowd, with the lights …”

After leaving the Northern Bass collective, Dave realised he needed a break from said music, crowd, and lights, and spent two years reassessing his priorities. He has recently been asked to collaborate in developing two new music festivals, an offer he is following up on.

“It takes a toll on you. Your dealing with United States times and UK times, you’re dealing with people who are slack getting their visas … you’re like a doctor on call. Then you’re putting your financial liability on the line on top of that as well. There was a point where I was no longer able to listen to music in venues because it became a place where people would lobby me. For instance when I was running the club and I just wanted to be left alone and get into the music I’d have people tapping me on the shoulder, wanting to talk bookings and so on. That’s why the last couple of years I’ve taken it slowly. I left Northern Bass because it was like ‘hold on, do I really want to be doing this?’ Plus I had neglected other passions in my life which give me enjoyment. Astronomy, bird watching. I needed to come out of the nerd closet! [laughs] But now I’ve taken time out and I’ve looked at what I want to be doing, and there’s certain kinds of music I still want to be doing. As long as that makes up the majority of what I do, I’ll be happy. I still love organising things. I still like putting things together. I still like dealing with the interesting people worldwide I deal with. I still like having dinner or a drink with these interesting artists and people.”

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air